Written by Lawrence Schenbeck

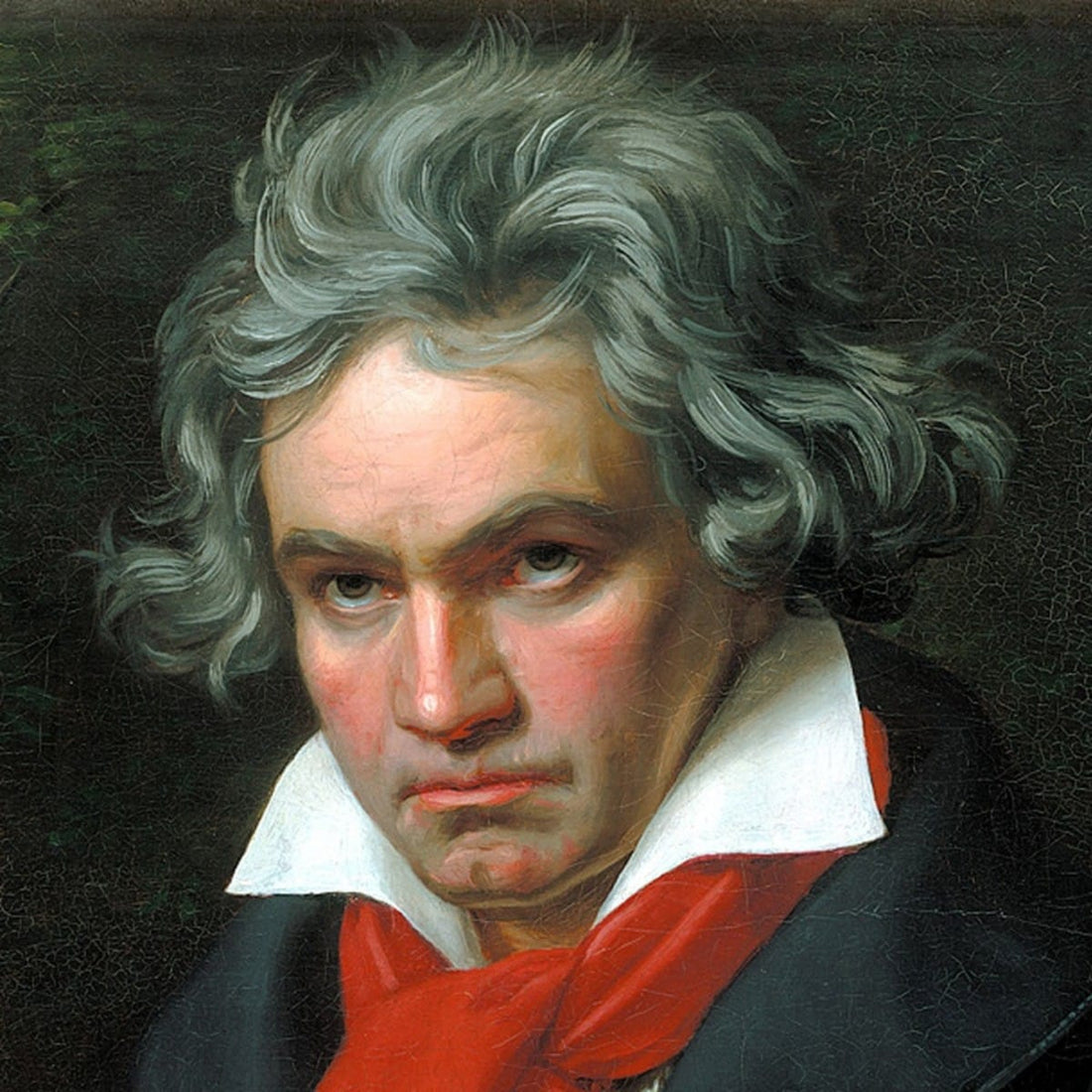

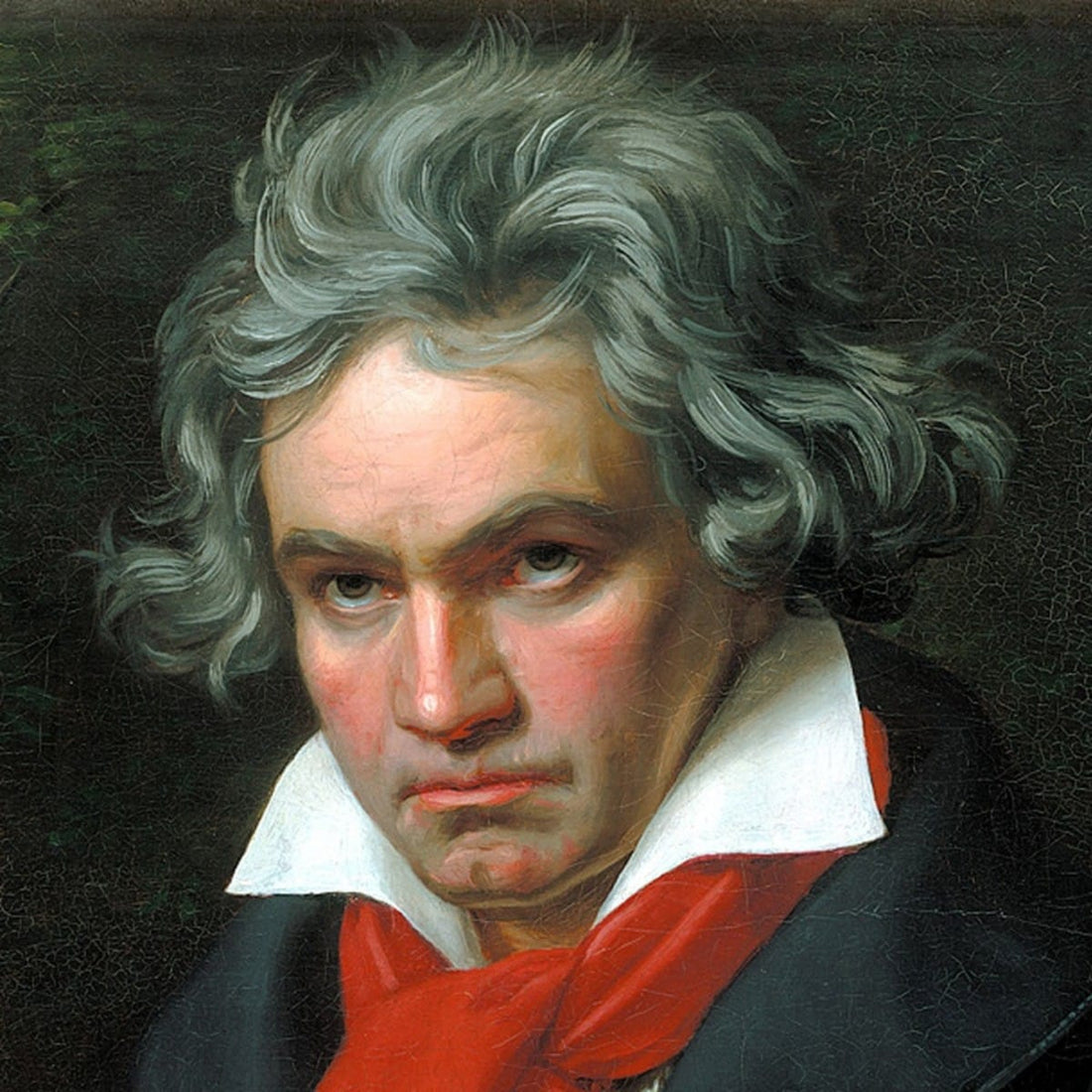

I’m pretty sure I discovered Ludwig van Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony as a sixth grader. There it was, an LP in a hardware-store rack in my little town, and I bought it. Nice cover:

an oil painting of a rural landscape, storm clouds gathering overhead as two men, one on horseback, make their way along a rustic carriage path. The record inside? Mercury MG 50045, Living Presence High Fidelity, Olympian Series. Among the “Hi-Fi Facts” included on its back cover was this:

Save for the element of enormous dynamic range, the most obviously spectacular portions of the Pastoral

Symphony—the last three sections—present the fewest problems for recording. The real test for Mercury’s Living Presence

recording technique exist in the first two movements, where the musical texture is exceedingly rich, complex, yet scored for strings, woodwinds and French horns only.

The uncredited writer of those words was probably Wilma Cozart, who by 1954—when MG 50045 was recorded—was a vice-president at Mercury and in full charge of its tiny classical division. She added that

a single Telefunken microphone was hung approximately 15 feet above and slightly behind the conductor’s podium and maintained in constant position throughout the recording sessions. . . .The success with which this recording captures the musical dialogue . . . of the Scene by the Brook

reflects the essential nature of Living Presence

recording more truly than many a more spectacular sonic tour-de-force.

Speaking of

tours de force, the beginning of the symphony isn’t one. As a sixth-grader, I was taken aback by its bouncy, slightly prosaic tone:

(That, not incidentally, is Marek Janowski conducting the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne in a very fine new Pentatone recording. Doesn't sound prosaic in their hands, does it?)

There’s a momentary pause after the first phrase; perhaps that makes it an introduction. Then the music ambles on, not exactly reminiscent of those thunderbolts that launch the Third or Fifth Symphonies. Reminds me more of the no-nonsense way Gershwin starts An American in Paris (Fiedler, Boston Pops):

In both cases, our hero has only just arrived. (Of course there’s a hero! Or at least, in Beethoven’s version of the countryside, an imagined protagonist.) LvB subtitled this movement “Awakening of Cheerful Feelings upon Arriving in the Country,” another way of telling us the music is “more an expression of feeling than of painting.” It's not an old-fashioned Baroque descriptive work like Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

A century later, having written American in Paris, Gershwin asked his friend Deems Taylor to devise a storyline for it, so Taylor came up with this: “Imagine an American swinging down the Champs Élysées on a mild, sunny morning. . . .” Our American is awakening to his cheerful feelings in the City of Light.

The first movement of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” maintains a sunny mood throughout its modest length, avoiding minor chords and developmental drama. One critic praised its “sublime monotony.” I wouldn’t go that far myself, not with the example of Vaughan Williams so close at hand: no part of Beethoven’s Sixth is “just a little too much like a cow looking over a gate," as various people may have said variously about RVW.

The bucolic bliss of Beethoven’s second movement, a “Scene by the Brook,” proves my point. It’s marked Andante molto mosso. Sometimes performers overdo the molto mosso part:

That was Janowski and the WDR SO again. Let’s compare their "Scene" with that in another new release, this from the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin (Harmonia Mundi):

A bit more bucolic, right? It's not simply a matter of tempo, but of phrasing, shading, accent. At the end of the movement, Beethoven provides cadenzas for various twittering creatures, which the Akademie’s players handle with aplomb:

In the scherzo, the locals hold a barn dance. But a storm is brewing, and when it breaks out, piccolos, trombones, and timpani join the fray, while birds, beasts and humans run for cover. Once the clouds clear, Beethoven provides a lovely, grateful “Shepherd’s Song” in conclusion.

I like both these recordings. Your choice may come down to couplings and sound quality: Janowski’s multichannel SACD offers an explosive Fifth and spacious, warmly resonant acoustics, while the Akademie offers more intimate sound and a genuine historical curiosity, Le Portrait musical de la Nature by Justin Heinrich Knecht (1752–1817). Knecht was a respected Rhenish composer whose Portrait was advertised in 1783 on the same page of Cramer’s Music Magazine as three piano sonatas (WoO47) by the 12-year-old Beethoven. Knecht’s five-movement sinfonia caratteristica offers scenes virtually identical to those in Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony. (This doesn’t mean little Ludwig stole the program from his elder; it does mean that human fascination with Nature has a long history.) Here’s a bit of Knecht’s “storm”:

Want to hear more of this kind of thing? Check out Jordi Savall’s Les Éléments: Tempêtes, Orages, & Fêtes Marines, which offers music by Locke, Marais, Rameau, Rebel, Telemann, and Vivaldi—no, not the Seasons!—in vivid performances on period instruments.

And now on to the Plus One part, where we check out some modern music that echoes or revises Beethoven. Lots to choose from, so we’ll mainly consider landscapes focused on flowing water: The Housatonic at Stockbridge, Night Ferry, and Oceans.

Charles Ives (1874–1954) led a remarkable life: as a New York City insurance man, he pioneered the concept of estate planning; as a musician his experiments drew praise from other rugged individualists like Gustav Mahler and Nicolas Slonimsky. Much of his orchestral output includes references to the natural world, but nearly all of it opens out onto broader social or philosophical questions. In Central Park in the Dark, for instance, ragtime music bleeds into the nocturnal quietude, suggesting a human restlessness quite at odds with any vision of the park as urban oasis.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=34AqNvhBfVQ

Ives's The Housatonic at Stockbridge may have been inspired by Robert Underwood Johnson’s pastoral poetry. But the composer was more affected by memories of a hiking trip taken with his wife Harmony after their honeymoon:

We walked in the meadows along the river and heard the distant singing from the church across the river. The mist had not entirely left the riverbed, and the colors, the running water, the banks and elm trees were something that one would always remember.

A tumultuous closing passage suggests that the primal peace of the river’s deep waters will not remain undisturbed forever.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4grS6KPGPA4

(Ives recommendation: three volumes from Sir Andrew Davis, Melbourne SO.)

Anna Clyne also drew upon poetry—Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner among others—and earlier musical “storm scenes” to compose Night Ferry for the Chicago Symphony in 2012. In this short video she explains how she created a visual roadmap of the work as part of her creative process. And here’s the whole piece, available as a high-res download from the CSO:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdVf3ni6sXE&t=7s

María Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir’s orchestral poem Oceans, from the Iceland Symphony Orchestra’s Concurrence (Sono Luminus DSL-92237), offers a very different seascape. It’s vast, primal, and colorful, a strikingly cinematic demonstration of her skill.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o10C7UCY3NQ

But that’s just one track on Concurrence, which is loaded with powerful new music. In Metacosmos, Anna Thorvaldsdóttir again shows her willingness to take greater risks than her peers. She's truly the Bard of the Glaciers, so I never expected to hear anything from her like this music's emotionally rewarding final section.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lTG4BVM8Pps

Haukur Tómasson’s Piano Concerto No. 2 features Vikingur Ólafsson, just one of the twittering creatures you’ll hear in it. (The opening measures actually pay tribute to to tvísöngur, the ancient Icelandic tradition of twin song.)

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdTGxpBT_hI

The album rounds off with Páll Ragnar Pálsson’s Quake. Whereas in Tómasson’s Concerto, the soloist is first among equals, here the solo cello may evoke a Beethovenian imaginary protagonist, “responding with panic and adroitness the rumbling, mysterious tumult all around.”

A word about the engineering of this remarkable album: Producer Dan Merceruio and chief engineer Daniel Shores have created yet another blue-ribbon demo disc for immersive sound. It’s mastered in DXD at 24b/352.8kHz and Native 7.1.4 for playback in Auro-3D or Dolby Atmos. At the very least, you need to hear it in basic multichannel in order to get the intended impact. This is not a gimmick. It’s an essential component of the music. I have no idea whether immersive sound will grow and prosper anew, thanks to Blu-ray and Atmos. But I know what I like, and I will continue to trust my ears. (Look for a TMT column soon about “immersive,” past and present.)

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.