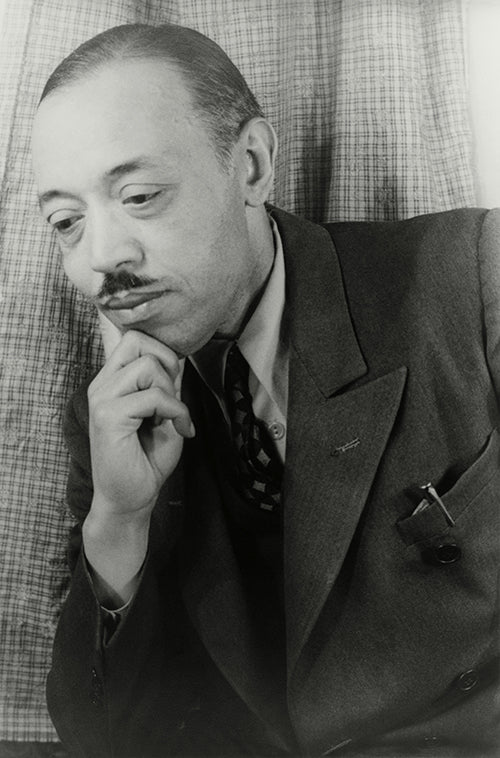

William Grant Still’s career might be described as good fortune and hard work forced to fight for air in a ruthlessly oppressive environment. As a Black boy raised in the Jim Crow South, Still’s prolific career as a classical composer is a tribute to his enormous determination. And he left behind the seeds for a new kind of distinctly American classical music. Several recent recordings bear witness to this.

Born in 1895 in the small town of Woodville, Mississippi, Still was raised in Little Rock, Arkansas by a schoolteacher mother and a stepfather (his biological father died when he was a baby) who loved classical music and brought home lots of records, which fascinated his son. By the time he was a teen, Still could play violin, oboe, clarinet, and several other instruments. He was also an excellent student, so his mother made sure he went to college at Wilberforce University in Ohio. But being the drum major there was not enough. He wanted a real music education.

At Oberlin Conservatory of Music, he studied privately with Edgard Varèse, the chance of a lifetime, until Still made the brave decision that he didn’t want to be a trendy composer who eschewed major and minor keys and experimented with electronic sound. He preferred to draw from the European classical tradition and flavor it with the gospel and folk music of his own heritage. So he transferred to the Eastman School of Music under the tutelage of the much more conservative George Whitefield Chadwick.

The result was a body of work that is still considered groundbreaking, for both musical and socio-political reasons. Still became the first Black composer to have a symphony performed by a major orchestra and the first Black person to conduct a major American orchestra. He, along with Florence Price, embodied the wish stated by Antonin Dvořák during his time in the United States that American composers should find a way to use their own rich musical world to inform and reshape the European tradition.

William Grant Still: Summerland/Violin Suite/Pastorale/American Suite, a recent release on Naxos by the Royal Scottish Orchestra under Avlana Eisenberg, not only demonstrates Still’s innovative hybrid style. It also boasts an interesting family connection: the violin soloist, Zina Schiff, is the composer’s great-granddaughter. In fact, family is something of a theme on the CD. Still was often inspired by his home life, dedicating his works to family members. There was even one for his dog, Shep.

Eisenberg filled the CD with world premieres. Although some of the pieces have been heard elsewhere, the conductor is the first to present their orchestrated arrangements, most of which were prepared by Still himself. One example is Pastorela, premiered here in its version for violin and orchestra. Schiff’s playing in this 1946 work shimmers with intensity.

Also in a version for violin and orchestra is 3 Visions: No. 2, Summerland. It shares Pastorela’s Debussy-like diffusion of orchestral sound and atmospheric dissonances. You’ll also notice melodic phrases reminiscent of Black spirituals, a genre that Still held close to his heart. Here Schiff’s playing is not an asset. Her contact between bow and string is too unpredictable, mussing the finer details in some passages.

One of the revelations of this collection is Still’s Threnody in Memory of Jean Sibelius, composed in 1965, seven years after the death of the great Finnish composer. Still’s brass writing alone shows his keen ear for capturing a particular style. He also manages to create a mournful Nordic melody, something that could not have been further from his personal experience. But he does sneak in some melodic ideas using the six-note blues scale.

The Royal Scottish Orchestra under Eisenberg plays by turns with a Romantic lushness and a Stoic earnestness.

Still’s pieces for violin have been receiving a lot of attention lately, but mostly in their better-known original versions with piano accompaniment. Fritz Gearhart’s William Grant Still: Works for Violin and Piano is on the Serayna label and features pianists Paul Tardif and Victor Steinhardt.

Tardif accompanies the Suite for Violin and Piano, composed in 1943, a work whose orchestrated version is on the Royal Scottish Orchestra disc. For each of the three movements, Still found inspiration in a sculpture by an African-American artist. The first, “African Dancer,” is named after a 1934 bronze by Richmond Barthé. Still’s piece is energetic and syncopated, evoking the raw power of a traditional ceremonial dance. Gearhart plays with a smooth, sweet sound that could probably use more grit to portray the music’s subject.

Gearhart’s gentle approach works significantly better in the second movement, “Mother and Child,” inspired by the art of Sargent Johnson. While Johnson did do a drawing with that title, he also created sculptures of Black mothers; presumably Still’s piece combines those works into one.

The violin melody is heart-rending, full of the unspeakable love, joy, worry, fear, and pride a mother feels for her child.

Remarkably, there is a third recording of the Suite that came out recently, a second in its version for violin and piano. Randall Goosby’s excellent album Roots, on Decca, includes it along with pieces by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Florence Price, and other Black composers, plus Dvořák and George Gershwin, both committed to including African-American musical language in their works.

It’s interesting to compare Goosby’s interpretation of “Mother and Child” with Gearhart’s. With Zhu Wang on piano, Goosby uses a breathy, almost earthy tone, quite different from Gearhart’s clear sweetness. With his intensity and rubato, Goosby pulls more sorrow from the score; there are moments where minor turns to major, and it feels like a mother has found the lost child she’s been grieving.

Movement III of the Suite is called “Gamin,” after a bronze bust that Augusta Savage made of her nephew in 1929. In a style distinct from the first two movements, “Gamin” has the mischievous energy of the young boy depicted in the sculpture. Still borrows heavily from the tonal language of early jazz and demands both virtuosity and humor from the violinist. Goosby has the challenge well in hand, keeping a sly bite to the rhythm even in the most difficult passages, and Zhu matches his sparkle and wit.

Despite the success of his Symphony No. 1, which was premiered by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in 1931, Still’s undeniable gifts were rarely acknowledged during his lifetime. The realities of racism kept him from having the career he deserved. According to his granddaughter, journalist Celeste Headlee, Still sometimes made ends meet by writing ditties for elementary school music textbooks, a job procured for him by Leopold Stokowski. Talk about over-qualified!

It’s heartening to see Still taken seriously as a composer now, even if he didn’t live to see it. As he once said of his music, “If it will help in some way to bring about better interracial understanding in America, then I feel that the work is justified.”

Header image courtesy of Wikipedia/Carl Van Vechten collection at the Library of Congress.