I must apologize to my valiant readers (all four of you) for the time lapse between Part Two (Issue 142) and Part Three. (Part One appeared in Issue 139.) I had a crazy summer professionally and personally. I trust you four are all well in these freakish times.

In 1978, on the heels of the hit movie Rocky, Sylvester Stallone used a script he’d written prior to Rocky for a new movie, Paradise Alley. Music producer Bones Howe has related that he doesn’t know how Stallone and Waits met, but suddenly Stallone was just there. Stallone gave Waits a small part in the movie, casting him as Mumbles, a salon piano player. Two Waits songs made it on the soundtrack: “(Meet Me In) Paradise Alley” and “Annie’s Back in Town.” Waits was thrilled at the chance to act, and a new career branch sprouted. Sprooshed. Sprang. Whatever.

Waits’ next non-musical project was to write the text for an art reproduction book of Peellaert paintings, titled Las Vegas – The Big Room. Waits liked the diversion, telling Rolling Stone, “Well y’know, ya have to keep busy. After all, a dog never pissed on a moving car…” That’s our boy.

In 1980 Francis Ford Coppola needed a film to help refill the bank with the money he’d lost on Apocalypse Now. Despite critical raves and the huge box office success, Coppola had spent a fortune on the film and needed to do something lighter and less expensive. Coppola had heard Waits’ music and wanted a kind of lyrical running score to complement the love story One From the Heart. Waits was interested in the idea but had become tired of the piano bar approach to his music and was looking for a new direction. Waits decided to do the project despite the “lounge operetta” theme Coppola wanted because first, Waits was given the entire score, and shoot, it was Francis Ford Coppola.

Unfortunately, Coppola was unable to rein in his budgetary appetite, creating a soundstage to duplicate the Las Vegas setting of the movie, with hotels, streets, shops, a replica of McCarran Airport complete with a jetway and a refurbished jetliner, and the spectacular blaze of the Vegas cityscape. Dude, just film it in Vegas like everybody else. Of course, Coppola isn’t everybody else.

On release, One From The Heart received poor reviews and grossed $636,796 after spending $26 million to produce. Eeep.

One happy result was that Waits got a cameo part and the experience of scoring a major movie, and he and Coppola became fast friends. Coppola loved Waits’ personal and artistic style, using Waits in four of his subsequent films, and having Tom sing at his daughter’s wedding.

Another bit of serendipity had Waits meeting his future bride and savior on the set. Kathleen Brennan was working as a story analyst on One from the Heart when she bumped into Waits, and Tom was in love. Waits and Brennan would later spin some different stories. I saw Brennan in the audience of an interview with Tom Waits. She was asked how she met Tom, and she said she was a nun in a convent and found Tom asleep in the church one morning. She was so captivated she gave up God for him. Waits naturally loved her rendition of how they met, and would repeat the tale often.

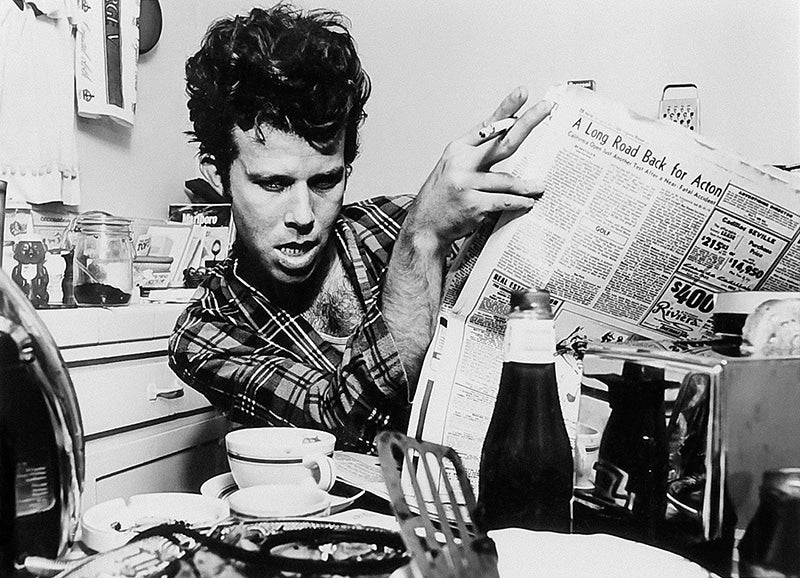

Whatever the circumstance of their meeting, it was the union of Waits and Brennan that would help create the new direction Waits was looking for, helped along by Kathleen getting Tom to quit smoking, cut down on the alcohol, and generally cleaning him up. She became his muse, his inspiration, and often his writing partner.

Waits’ film career continued with some 35 films after One From the Heart, right up to a new film, Licorice Pizza, to be released in 2021. He played Renfield in the 1992 Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Got to watch that one. In 1987 he played a bum in Ironweed with Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep. I did watch this one and I recommend it. It’s worth the watch to see Jack and Tom together. Waits on Nicholson: “Nicholson’s a consummate storyteller…You can learn a lot from him just by watching him open a window or tie his shoes.” High praise from a fellow consummate storyteller.

Back to the music. In 1983 Waits self-produced Swordfishtrombones, his first album since Heartattack and Vine. Here was a major stylistic change encouraged by Kathleen. The name is a tell. This stuff is like, well, a swordfishtrombone. Waits dropped the piano act and banished the sax entirely. The opening track “Underground” is a classic example. The entire approach of instrumentation and arrangement is a lot of fun and a real departure.

The album features master weirdo percussionists Victor Feldman and Francis Thumm. The assortment of percussive whiz-bangs, including metal aunglongs, marimbas, bass boo bams, brake drums, and bass drum with rice, afforded Waits fascinating undercurrents to his songs.

One tune, “In The Neighborhood’, is kind of a throwback but worth a listen just from his still-beautiful lyrics.

The next two entries are favorites from the recording. “16 Shells From a 30-Ought-Six” is a great recording and another example of Waits’ new direction.

This next is interesting just from the storyline. “Frank’s Wild Years” is a short story Waits wrote as a spoken piece, which eventually spawned an idea for a play that Tom and Kathleen co-produced, and which spent play time in a Chicago theater while they lost money. The arrangement goes back to an earlier feel, with Larry Taylor on acoustic bass and Ronnie Barron on the Hammond B3 organ.

“Frank hung his wild years on a nail he drove through his wife’s forehead.” Yeah, you can get a play out of that.

Elektra, Waits’ record label at the time, hated Swordfishtrombones, so he switched to Island Records instead of compromising, thank heavens. The album is a real hoot and should be savored like a martini shaken with an olive and a razor blade. Some of the cuts are definitely Waits Meets Zappa.

Rain Dogs, released in 1985, was written while Waits lived in New York and features street sounds recorded by Waits on cassette and used as backdrop on some tracks. Like Swordfishtrombones, Rain Dogs channels instrumentation that at times evokes Henry Mancini’s Peter Gunn, and in other places, Zappa. Bass players unite! Dig the bass track to “Midtown.”

The opening cut on the album again shows Waits new direction with a typical lyric for him, but the arrangement uses instrumental ideas born in Swordfishtrombones. With Marc Ribot from the Lounge Lizards on guitar, here’s “Singapore.”

Waits had gotten Keith Richards’ attention, and Tom certainly had a good day when he got Richards for three songs on the album. This next is “Union Square,” and I could have just thrown this out there and most of you would have been able to identify who played the guitar on this track.

Rain Dogs followed the usual pattern of critical raves and poor sales in America and successful sales in Europe, but by now Waits no longer cared, if he could keep doing as he pleased.

Waits took a cue from the track “Frank’s Wild Years” and wrote his next album, Frank’s Wild Years. The album contains songs used in the play of the same name, including three he co-wrote with Kathleen Brennan. One of the collaborations is “Please Wake Me Up.”

Gorgeous. I must meet this couple someday. I don’t know what I’d say, but I know it would be something I won’t forget. I recently spent 20 minutes with Bela Fleck and even though I was a blithering sycophant I know I won’t forget the encounter.

Bone Machine was released in 1992 and is a minimalist masterpiece. To continue with the “m’s,” Bone Machine is a magical, mystical, musical manifestation of mayhem. The difficulty in presenting this album in this article was how to choose which tracks to show you. Just do this… You can stream if you want, but my advice to my fearless dreamers is, just buy it. Trust me buy this album, do the guy a favor. But keep it away from flammables.

Waits produced and Brennan co-produced. The story of the recording has Waits booked into a studio he hated. He got no “vibe” from it, and getting that vibe was becoming more important with each work. He then found a storage room in the basement of the studio with a cement floor and a broken window. It was perfect. He recorded the album entirely in that room. The problem with the broken window was it looked out onto the street, so those street sounds, with cars passing by and airplanes overhead, would become part of the tracks.

Kathleen co-wrote eight of the cuts and they are all great. I’ll just throw one out there and trust you’ll check out the rest.

“Murder In The Red Barn” features Joe Marquez on banjo, Waits on drums/percussion and Larry Taylor on upright. And that’s all folks.

?list=PLTMN6OMDTnKlRQ2hAhGT_xZQ7jzggXhyN

One track with just our boy on bass and guitar is “Jesus Gonna Be Here Soon.”

“Black Wings” is a spooky tune, co-written with Brennan, with Larry Taylor on that upright, Waits on drums and rhythm guitar, and Joe Gore on those neat western Tele licks.

Bone Machine deservedly won a Grammy for Best Alternative Music Album.

I will wrap this series up with a Part Four that continues with Waits’s life and some of the last albums. Unless I get in trouble with the law. If you don’t get my letter, you’ll know that I’m in jail.