The origins of music are generally linked to mythological, religious, and/or philosophical beliefs. Ancient Chinese musical instrumentation, for example, was used in order to appeal to the supernatural, for dance, and for spiritual expression. During the Byzantine Empire, music was used in church services, dramas, ballets, banquets, festivals and sports. The origins of jazz are linked to both European musical structure and African rhythms. Jazz can also be traced back to ragtime and the blues. Given music’s rich history covering thousands of years and many different cultures, is it a stretch to say that all music – in varying degrees – is derivative?

Archeologists tell us the oldest musical instruments known to man are bone flutes dating to 40,000 years ago. Neanderthals crafted these ancient flutes from the bones of young bears, large birds, and the ivory of mammoths. Scholars have debated whether the flute holes were natural teeth marks created by animals on the hunt, though their symmetry and spacing strongly suggest they were man-made.

Is it possible that Neanderthal “flautists” dabbled in a form of music creation? They clearly lacked the brainpower to compose by any standard that we know, but who’s to say that stringing together a few notes didn’t make for an original composition? Of course, there were no copyright laws to safeguard against infringement, though any dispute could easily be settled with a spear or rock to the head. Yep, jurisprudence comes in many shapes and sizes.

In a more modern-day scenario, the guitarist/songwriter Eric Clapton traces his musical roots to guitarists Big Bill Broonzy, Muddy Waters and others. In his autobiography, Clapton notes, “I would take the bits that I could copy from a combination of the electric blues players I liked, like John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and Chuck Berry, and the acoustic players like Big Bill Broonzy, and amalgamate them into one, trying to find a phraseology that would encompass all these different artists.”

So, where does the line between emulation and appropriation begin and end? It’s a nice tribute and compliment when Clapton (and others) acknowledge the influence their musical idols have had on their own music. Given his public acknowledgment, could a crafty musicologist build a case for appropriation filed by an heir of one of Clapton’s idols? Yes, a 12-bar blues progression is both foundational and somewhat timeless, but who knows? Seemingly anyone can sue anybody for just about anything these days. A greedy attorney might say to a prospective plaintiff, “We got a real good case here (aka money). Of course, you’ll need to exhibit outrage about protecting your late Uncle Bill’s legacy, with lots of righteous indignation.”

Many of us are familiar with the widely publicized copyright infringement case between Led Zeppelin and the estate of the late Randy California, founder of the band Spirit. Led Zep was accused of appropriating (okay, stealing) the opening riff to “Stairway To Heaven” from Spirit’s song “Taurus,” released in 1968 and written by California. By 2008 it was estimated that “Stairway” had amassed $562 million in royalties, so a successful lawsuit could have potentially yielded millions in past and future royalty payments. Essentially, the estate viewed “Stairway to Heaven” more like “Stairway to Seven,” as in a possible seven-plus-figure payout. (In the YouTube video below, the “Taurus” riff comes in at about 0:45.)

In court documents the estate of Randy California claimed that, since both bands often were on the same concert bill in 1970, before “Stairway to Heaven” was conceived, Led Zep had frequent exposure to the alleged similar-sounding “Taurus.” Ultimately, a judge and jury agreed with musicologists’ testimony that the chord progressions in “Stairway” had been in use for decades. The estate was then denied a second time on appeal.

Another infringement case in 1991 involved Vanilla Ice and his hit record “Ice Ice Baby.” Without credit or permission, the Iceman sampled elements of the song “Under Pressure,” recorded by David Bowie and Queen. The case was settled confidentially with Ice having to pony up a sum of money.

More recently, pop star Dua Lipa was teed up with two copyright suits claiming infringement on her hit song “Levitating.” One suit claims the song is “substantially similar” to both the 1979 Cory Daye song “Wiggle and Giggle All Night,” and the 1980 Miguel Bosé song “Don Diablo.” The second suit was filed on behalf of the reggae band Artikal Sound System, claiming “Levitating” infringes on their 2017 song “Live Your Life.”

Forensic musicologists are often called upon as expert witnesses in cases of copyright infringement. Most have a doctoral degree in music, with a focus on music history, theory, and/or composition. They may also be composers, conductors, performers and/or educators. Their legal qualifications are not as relevant as their “expert” musical opinions. In 1923, British justice John Astbury stated, “infringement of copyright in music is not a question of note-for-note comparison, but whether the substance of the original copyright work is taken or not. It falls to be determined by the ear, as well as by the eye.” Whether by ear or eye, none of this is what you’d call an exact science. It’s all quite subjective.

Looking towards the future, technology will undoubtedly play a large role in cases of infringement and provenance. Artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and forensic linguistics, for example, can determine with a high degree of accuracy if a range of writings allegedly penned by two different people were written by the same person. It’s based on patterns and word usage. Similarly, the art field is already using blockchain technology to track the provenance and authenticity of artists’ creations (paintings, photographs, sculptures, etc.), an important step for an industry that’s historically vulnerable to fraud.

In regards to safeguarding a musician’s creation and provenance, Yvette Liebesman, a law professor at St. Louis University, has proposed a system called Mega-Element Analysis. In this system, computers would compare elements of a song against a database of similar songs, though the amount of data and manpower required to make the system operational and effective may be prohibitive. Two researchers, professor Daniel Müllensiefen and Dr. Marc Pendzich, have developed a system that compares elements of a song’s melody that are copyrightable using MIDI files, a cornerstone of music production software. A MIDI file – short for Musical Instrument Digital Interface – can identify every note played by every instrument, and can be used to isolate variables like timing, pitch, and tempo. Many view MIDI files as sheet music for the 21st century. Though the Mullensiefen-Pendzich system is not without limitations, it has yielded strong results in beta-type testing on copyright infringement cases.

The process of music creation today has never been as different or as easy. There’s an assortment of music production software available to aid aspiring composers with content development. It’s no wonder roughly 60,000 songs are uploaded to Spotify every day. A musician no longer needs access to a professional studio, or gobs of money for expensive equipment. The really good software is designed with a friendly, easy-to-use interface. Essentially, the production software becomes a music-writing partner, delivering both speed and efficiency to either a seasoned or novice composer.

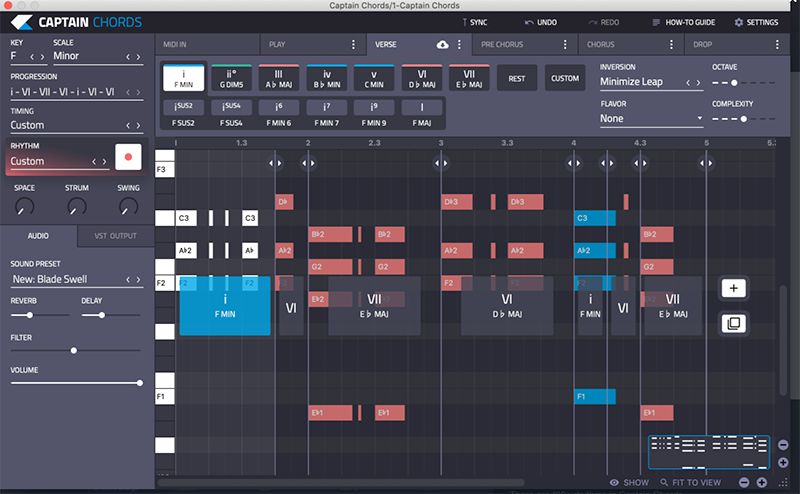

For example, Mixed in Key, a leading music-production software company, offers composers a suite of plugins. Their “Captain Chords” plugin lays down the framework for a song, “Captain Deep” adds some bass, “Captain Melody” delivers, well, melody, “Captain Beat” imports drums, and “Captain Play” brings it all together. All a musician needs is a germ of an idea, and in theory (or practice) the software can build the rest.

Screen shot, Captain Chords music production software. From the Mixed in Key website.

I see no harm in using music production software for creative stimulation, but an over-reliance on its use certainly lacks in originality. It also has the potential for dehumanizing, commoditizing and automating the entire music creation process. Perhaps I’m too much of an old-school purist, but there’s a sense of artificiality to the process that, well, almost feels like cheating. It’s a bit like if a student driver took their road test in a self-driving car. My friend Dan, an aspiring musician in his own right, succinctly sums it all up this way: “the (software) tools should be used to break the kink in the flow, not as a musical crutch to stand on.”Yes, modern-day technology can be both a blessing and a curse, depending on how it is utilized. When technology is used as a tool for learning, creative stimulation and so on, it has great value. If and when the technology fundamentally becomes the end product – especially in fields historically driven by an artist’s creative and imaginative thinking – then that’s where I believe lines can get blurry and even crossed.

Hopefully, advances in technology will help keep the provenance of artists’ music clean and unencumbered, certainly a desirable and worthy goal. Let’s also hope that modern-day music production software doesn’t lead to a decline in both artists’ creativity and originality.

In sum, music has never been easier to both create and distribute. That’s great news for music creators! The bad news is, given the vast amount of content available today across an array of streaming services, both discovery and curation for music lovers has become increasingly more challenging.

Header image: Aurignacian flute made from an animal bone, from circa 33,000 to 37,000 years ago. Courtesy of Wikipedia/José-Manuel Benito.