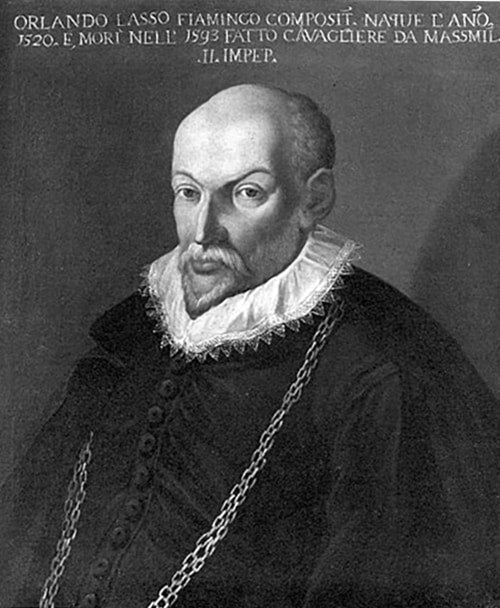

One of the most astonishing periods of European music history was the 16th century, when composers like Josquin Des Prez and Giovanni Palestrina rocketed polyphonic vocal writing to new levels of beauty. Among that exclusive group was Orlande de Lassus, who was recognized in his own time as one of the best crafters of music for voice. Several recent recordings serve as reminders of his tremendous skill.

Lassus (also known as Orlando di Lasso, among several other variants) was born in the Habsburg Netherlands, which is today called Belgium, in about 1532. When he was 12, he received his musical education in several Italian cities, including Mantua and Milan. His compositional career began in Naples, where he found a patron, only to be hired away by the wildly rich Medici family to serve them in Rome. The Catholic Church commissioned some pieces from him there as well. As a Netherlander working in Italy, Lassus followed in Josquin’s footsteps from more than a generation earlier (learn more about Des Prez in my piece for Copper in Issue 132).

One of the new Lassus recording reminds us of the range of wealthy patrons he worked for. Le nozze in Baviera, featuring Ensemble Origo on the Naxos label, includes the music Lassus was commissioned to compose for the wedding of William of Bavaria and Renate of Lorraine in 1568. The contents of this album are fascinating. As Ensemble Origo’s director, Eric Rice, explains in the liner notes, the moresca was “an Italian musical genre that caricatured Black Africans.” If you’re starting to squirm, that’s exactly what’s intended. Rice, who is white, has taken it upon himself to confront these racially problematic songs head-on.

Moresche were considered entertaining in mid-1500s Italy, at least among the upper classes, so including them in any elaborate gathering was desirable. It’s quite a dose of reality to learn that a revered church composer like Lassus contributed to this genre. There are eight of them on this recording. According to Rice, although there are no instruments mentioned on the surviving vocal score, it’s reasonable that instruments might have played along at a well-funded affair. Therefore, Rice has written them into his arrangement.

“O Lucia, Miau Miau” is an example of a morisca. It’s written for two voices, to which a viol line has been added.

The idea of the moresca is to caricature the speech patterns of North Africans (“Moors”). If you would like to see the libretto (warning: explicit language), you can do so here:

https://static.qobuz.com/goodies/24/000139142.pdf

Origo’s singers are not always spot-on with intonation, but their timbre is convincingly 16th-century. While this is not the first recording of these moresche, they are usually misclassified as other genres, such as madrigals or villanelles. It’s intriguing, if disturbing, to see them presented for what they really are.

The William/Renate wedding celebration lasted 18 days, so Lassus needed to write a lot of music! Since a ceremony in church was involved, some of that music is sacred polyphony. Gratia sola Dei would have been sung at the wedding itself. If not as intense in sound as some Lassus sacred recordings, the Origo performance is reverent, and the high-frequency viol sounds give the piece an unusual color. That late in the Renaissance, it is possible that strings might have played along even in a church, even if this is not the standard interpretation of this music.

Lassus is much better known for his sacred than his secular work, and he’s rarely recorded using instruments. For a recent and more conventional approach, there is much to be enjoyed in Lassus: Inferno, a collection of the composer’s Latin motets on Harmonia Mundi, with Cappella Amsterdam under the direction of Daniel Reuss. By the 16th century, the term “motet” referred to polyphonic vocal settings of texts from the Bible, as it would through the 19th century. (Originally, in late medieval music, a motet could be sacred or secular, and sometimes both at once, with multiple texts being sung simultaneously.)

“Circumdederunt me dolores mortis” (“The sorrows of death surrounded me”) is Lassus’ six-part setting of Psalm 17. It’s a late work, from 1601. Cappella Amsterdam’s sound is dense and smooth, as Lassus likely intended in order to take advantage of church acoustics. The slight tugs at the meter and the way the group leans into dissonances shows how well Reuss understands the emotional transparency of Lassus’ style. That’s something the composer would have learned from Josquin’s music.

Cappella Amsterdam is a small choir, with a few singers assigned to each part. Lassus’ music takes on an even more intimate sound when only one person sings each line. That’s what distinguishes Psalmus, the latest recording by the Munich-based, six-member group called Die Singphoniker. The all-male ensemble records for CPO in collaboration with BR Klassik.

The centerpiece of this project was to preserve the special setting of the Seven Penitential Psalms that Lassus did as a commission for Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria. What makes this setting special is its purpose, to be part of what we would today call a multimedia presentation: a book with the Psalm texts, music, and paintings that illustrate their meaning. The last element was provided by Hans Mielich, a painter based in Munich, and the whole thing was published in a two-volume codex (the term used for a manuscript that binds together multiple items).

Unfortunately, the CD booklet does not include any reproductions from this codex, which is held at the Bavarian State Library. Here’s one breathtaking example: (click on this link).

The music is just as richly appointed, and Singphoniker – plus special guests soprano Helene Grabitzky and countertenor Andreas Pehl – show off its magnificence with clear, ethereal singing. The voices are superbly blended and the phrasing gives a continuous sense of motion.

Although Lassus wrote hundreds of short works like madrigals, moresche, and psalms, he also received many commissions for larger-scale pieces. His surviving setting of the St. Matthew Passion rivals Bach’s for gorgeous and dramatic polyphony (no new recordings, but the 1994 Harmonia Mundi disc with Paul Hillier’s Theatre of Voices is spectacular). More commonly, he wrote Masses. There was a constant need for new musical versions of that often-used liturgical material.

On Decca Eloquence’s Lassus: Choral Music, two renowned British choruses join forces to present four of Lassus’ Masses plus a few motets. Stephen Cloebury conducts the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, and Simon Preston leads the Christ Church Cathedral Choir, Oxford. This is a rerelease of recordings from 1996.

The sound and style could not be more different from Singphoniker’s. Nowadays, when early-music historical performance practice influences every attempt at music written before 1800 (and sometimes these days, music before 1900), it’s surprising to hear a Renaissance work presented with a massive choral sound. Very 1960s. But there’s no denying the power of two great choirs singing great compositions under the direction of two great conductors. At the risk of being trite, the atmosphere seems to pulse with a throng of angels singing. Crank up the volume, and you’ll see what I mean.

Lassus would have gotten chills.

Header image courtesy of Wikipedia/public domain.