Over the past few months, our esteemed editor Frank Doris has been sharing with us his personal choices for a desert island collection of rock albums (as per his list of 150 favorites in Issue 150). I thought it was high time that someone made the same kind of list for classical music (though it should be noted that Don Kaplan has been covering desert island, recommended, and other varieties of classical music in his “The Mindful Melophile” column, Anne E. Johnson writes about classical music in her “Something Old, Something New” articles, and Larry Schenbeck was a past classical music contributor).

Before I jump into my list, I need to offer a few important comments:

- Obviously, this list reflects my taste. Yours may be entirely different. In fact, it’s very likely that it is. So, if you hate my choices, I totally understand. But we can still be friends.

- My tastes run largely to orchestral music and opera, primarily from the late classical period through to the middle of the 20th century. While I certainly enjoy instrumental and chamber music, they’re not generally my first choice.

- Wherever possible, I’ve tried to provide catalog numbers for the recommended recordings. However, since many recordings are available on vinyl, CD, SACD and as downloads (in different formats) and each format has a different catalog number, it was not always possible to do so. But a quick Google search (or a search of your favorite music site) should easily find the format you prefer.

- Like Frank, I’m going to break this article into multiple parts. Truthfully, if I was stranded on a desert island (putting aside the issue of where I would plug in my equipment), I would want to have the entirety of my music collection with me. And given that it all fits onto a portable USB drive (albeit a big one), that would even be possible. But this is supposed to be a list of the essential music that I couldn’t live without. So without further ado, here goes:

[Editor’s Note: the video clips may not be the same as the performances noted, but are included to give an idea of what the artists might be like.]

BACH: Goldberg Variations. Glenn Gould, 1955; Pristine Classical PAKM062

Here’s an album that needs little introduction. Glenn Gould’s breakthrough performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variations has been a kind of gold standard for decades. While some of his choices around tempo and dynamics may be controversial, this is a recording that must be heard over and over. Gould’s contrapuntal playing is without peer and he influenced a generation of pianists who followed him. Andrew Rose of Pristine Classical has done wonders with the original recording, rendering it far more full-bodied and three-dimensional.

BACH: Mass in B Minor. Philippe Herreweghe, Collegium Vocale Gent; PHI LPH004

During the long days of the COVID-19 pandemic, my choir (which was unable to rehearse, for obvious reasons) conducted an online poll and selected Bach’s Mass in B Minor as their all-time favorite choral work. I was one of the few dissenters (personally I lean toward the Brahms Requiem) but it’s hard to argue with the greatness of this work.

In truth, there are a number of very fine recordings of this remarkable mass and I was hard-pressed to choose a favorite. Jos van Veldhoven and the Netherlands Bach Ensemble (Channel Classics CCS SA 25007) deliver a swift, minimalist reading that is fascinating for its use of small forces. René Jacobs with the Akademie für alte Musik Berlin also offers a strong performance with – unsurprisingly – some unusual tempo choices, and John Eliot Gardiner with the English Baroque Soloists on Archiv is always a safe choice. But in the end, it came down to a choice between this – Herreweghe’s third recording of Bach’s great mass – and Masaaki Suzuki with the Bach Collegium Japan on BIS. Ultimately, I chose this performance because the recording itself is magnificent, allowing all of the individual voices to shine through. But frankly, you would be well served with any of the performances above.

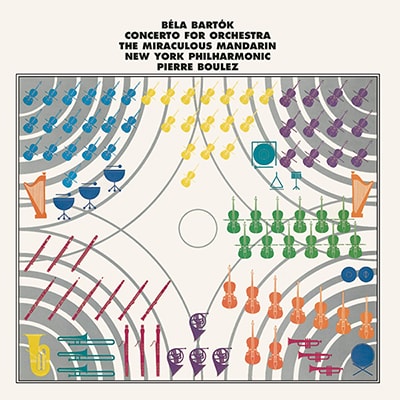

BARTÓK: Concerto for Orchestra. Pierre Boulez, New York Philharmonic; Sony Classical

Someone once said that “Boulez is brilliant in music he loves” and it’s clear that he loves Bartók. After all, he’s recorded this work at least twice (this one, and a later recording with the Chicago Symphony) and made a documentary with the Berlin Philharmonic. Bartók’s last major work for orchestra, the Concerto for Orchestra is also among his most popular compositions and it’s easy to see why. While it still contains strong dissonances, the music is largely accessible: in some sections highly motoric and forward-moving while in others, soft and contemplative.

This recording was originally made in quadraphonic sound (anyone remember Quad?). The album cover even shows the orchestra in four distinct corners. However, to my ears, the current issue sounds like a conventional stereo recording. Like many of Boulez’ recordings this one has great transparency and rhythmic surety, two qualities that work exceptionally well with Bartók’s music. While the later performance (on DG) is similar in many ways, I prefer the sound of this one. Available on SACD or as a high-resolution FLAC download.

BEETHOVEN: Fidelio. Otto Klemperer, Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus, Christa Ludwig, Jon Vickers, Walter Berry, Gottlob Frick, et al; Warner Classics

Beethoven’s only opera is often described as problematic. A lot of it is very static and it levels huge demands on the vocalists. Sometimes it actually works better on record than in the theater. Recorded in the early 60s under the supervision of the legendary Walter Legge, this recording is an evergreen. Christa Ludwig, a mezzo, nevertheless delivers a thrilling performance in a role traditionally taken by a dramatic soprano. Listen to her effortless vocalism in Abscheulicher. Jon Vickers, at the peak of his career, delivers an emotionally torrid performance in the relatively brief role of Florestan. Walter Berry is a menacing Pizzaro and Gottlob Frick a deeply sympathetic Rocco. The rest of the cast is equally fine and the Philharmonia Orchestra plays its heart out. Finally, to say that Otto Klemperer feels a deep sympathy for this music would be a vast understatement.

BEETHOVEN: Missa Solemnis. Otto Klemperer, New Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus; Warner Classics

Otto Klemperer’s Beethoven is widely esteemed, although, to make a personal confession, I’ve never been a huge fan of his recordings of the symphonies. While they possess that granitic quality for which he was renowned, to my taste they are lacking a bit in momentum.

That hesitation emphatically does not apply to this recording of Missa Solemnis (or, for that matter to his definitive recording of Fidelio). This is a performance for the ages with a quartet of brilliant voices, Wilhelm Pitz’s highly trained Philharmonia Chorus and the New Philharmonia Orchestra playing to its usual standard of excellence. I have heard many performances of this work (I’ve even performed in it myself) but none of them has ever come close to this one.

BEETHOVEN: Symphonies No. 5 and 7. Carlos Kleiber, Vienna Philharmonic; DG

I had the rare privilege of seeing the brilliant but eccentric Carlos Kleiber in 1978, during one of his very infrequent appearances in North America. Conducting a program of Weber, Schubert and Beethoven with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, it was one of the standout concert experiences of my life. In spite of his very limited performance repertoire and his increasingly rare appearances, Kleiber was voted the greatest conductor of the 20th century by an audience of his peers.

Kleiber’s traversals of Beethoven’s Fifth and Seventh symphonies are nothing if not definitive. While I have heard many very fine performances of these symphonies (including wonderful recent recordings from Manfred Honeck and Teodor Currentzis), none of them quite equals the sense of inevitability that each of these performances conveys. Listen, for example, to the way in which Kleiber uses the timpani to punctuate the climaxes in the first movement of the Fifth. No other conductor that I’ve heard manages to make this quite so effective. Wagner famously referred to Beethoven’s seventh symphony as “the apotheosis of the dance.” You can tell that Kleiber feels this and manages to bring the dance alive in every movement of the symphony.

This performance is also available on SACD or as a downloadable high-resolution FLAC.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 9. Manfred Honeck, Pittsburgh Symphony; Reference Recordings FR-741

Truth to be told, my favorite performance, of this, Beethoven’s final symphony comes from Toscanini’s 1939 Beethoven cycle with the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Pristine Classical has done a remarkable job on the restoration of that cycle. For me, that performance has almost everything – drama, probing intensity, fabulous playing and a great quartet of soloists. However, the one thing that it doesn’t have is great sound, despite Andrew Rose’s fine work.

Manfred Honeck’s performance on Reference Recordings, part of an ongoing Beethoven cycle with the Pittsburgh Symphony, most emphatically does have wonderful sound and a performance that – to my ears – comes close to equaling Toscanini’s drive and intensity. As usual, the playing of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra’s is beyond reproach.

BERLIOZ: La Damnation de Faust. Sir Georg Solti, Chicago Symphony, Kenneth Riegel, Frederica von Stade, Jose Van Dam; Decca

Arguably, this is one of Berlioz’ greatest masterpieces. Neither an opera nor an oratorio, he called it a “Dramatic Legend.” Notwithstanding its complex structure, it is frequently presented as a stage work, including a brilliant production at the Metropolitan Opera created by Robert Lepage (available as a video and as an audio download). This is also a work that is much loved by conductors, as witnessed by the number of great conductors who have recorded it. That list includes Colin Davis (a renowned Berlioz specialist), Simon Rattle, Wilhelm Furtwängler (!), Kent Nagano, James Levine, Georges Pretre, Eliahu Inbal, Bernard Haitink and many others, including the recording above.

The music consists of a series of scenes drawn from the epic Goethe play, showcasing a brilliant array of moods, from the pomp of the Rakoczy March, to the fairylike Dance of the Sylphs, and the bombast of the demons’ chorus.

Ultimately, there is no such thing as a perfect performance. There are always compromises, and I can only make recommendations based on the recordings that I have actually heard. This particular one is brilliantly played by the Chicago Symphony, extremely well recorded by Decca, and offers a solid cast of soloists.

BERNSTEIN: Candide. Leonard Bernstein, London Symphony, Jerry Hadley, June Anderson, Christa Ludwig, Nicolai Gedda, et al; DG

During his lifetime, Leonard Bernstein often expressed frustration that he was better known as a conductor than as a composer. Ironically, and like so many other great artists, it took a few years after his death before his remarkable gifts as a composer came to be fully appreciated. Candide was created after he was approached by Lillian Hellman, who wanted him to write incidental music for a play based on the novella by Voltaire. Bernstein became so enthused by the idea that he decided to write a full-fledged operetta instead.

That operetta has undergone many changes, the most significant being the replacement of the original Lillian Hellman libretto with a new one by Hugh Wheeler. But Bernstein’s brilliant, sparkling music remains the main attraction and with the composer at the helm and a luxury cast (including Christa Ludwig and Nicolai Gedda in small roles), this recording does total justice to his vision. While it may not have the gravitas of a Mahler symphony or a Wagner opera, you will be hard-pressed to find a recording that is as much fun as this one.

BIZET: Carmen. Lorin Maazel, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Anna Moffo, Franco Corelli, Piero Cappuccilli, Helen Donath, José Van Dam; RCA

Bizet’s Carmen has sometimes been referred to as the Queen of Opera. And for good reason. Can you think of another opera that contains so many well-loved tunes? It’s also a showpiece for its three leads. If you have a strong Carmen, Don Jose and Escamillo, you are pretty much assured a wonderful evening at the opera.

I know that there are arguments in favor of the Callas, Gedda, Pretre recording, as well as de los Angeles, Gedda and Beecham. And those recordings certainly have their strengths.

This particular recording, from 1970, features Anna Moffo nearing the end of her career but before her vocal difficulties became obvious. She is in fabulous voice here. She is matched by an ardent Don Jose in Franco Corelli. Although his French accent is sometimes non-idiomatic, it’s certainly no worse than Placido Domingo who sang (and recorded) this role many times. Piero Cappuccilli exhibits plenty of swagger as Escamillo and Helen Donath is a meltingly sweet Micaëla. Many of the minor roles are filled by great singers in the early years of their careers, including Arleen Augér, Jane Berbié and José Van Dam.

Lorin Maazel can sometimes be willful in opera, but here he leads a straightforward reading with fabulous playing by the orchestra of the Deutsche Oper Berlin along with their strong chorus. The recording quality is excellent.

BRAHMS: Ein Deutsches Requiem. John Eliot Gardiner, Monteverdi Choir, Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique; SDG SDG706

To beat a tired drum, this is another work that I’ve been privileged enough to sing many times and it happens to be one of my favorite choral works, even if George Bernard Shaw did quip that it is ”patiently borne only by the corpse.” In fact, it is a magnificently constructed piece of music, with some of the most ethereal moments in the choral repertoire. Virtually every major conductor has taken a crack at the work, including Klemperer, Solti, Karajan, Giulini and numerous others. Sir John Eliot Gardiner has recorded it twice, and this is his later traversal, recorded live at the Usher Hall in Edinburgh, in 2008. You will be hard-pressed to find a recording where the music and the words blend together so splendidly.

BRAHMS: Piano Quintet in F minor Op. 34. Maurizio Pollini, Quartetto Italiano; DG

I mentioned George Bernard Shaw’s rather sharp opinion about Brahms’ Requiem. His opinion, however, was entirely different when it came to Brahms’ chamber music, an opinion that I strongly share. I recently attended a competition of young classical performers and – for me – the performance that really grabbed me was a young Mexican violinist playing Brahms’ third violin sonata.

All of which is a long-winded way of me saying that I have a deep and abiding love of Brahms, and particularly this early quintet. A friend of mine, a Russian-Canadian pianist and accompanist who graduated from the Gnessin State Musical College in Moscow (one of the leading music academies in Russia) said it all when she said, “What a performance!” I echo that sentiment; this is a beautifully played, highly dramatic account of this great work. Available as a high-resolution download.

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1. James Levine, Chicago Symphony; RCA

Brahms’ First Symphony was the first of his symphonies that I ever heard played live and it left a lasting impact and a lifelong love for the music of the great German composer. Recorded during his heyday as the music director of the Ravinia Festival, James Levine’s cycle of Brahms symphonies with the Chicago Symphony remains one of the outstanding recordings of this music. In my opinion, it is far better than his later cycle with the Vienna Philharmonic. And this performance of the first symphony is the standout performance of the cycle. Clear, concise, dramatic and gorgeously played, it exudes the youthful energy of both composer and conductor. Listen, for example, to the opening of the first movement which sweeps along with an inevitability that many other performances seem to lack. I recognize that James Levine had a very checkered past, and some listeners may feel uncomfortable with his recordings, but it’s hard to ignore the greatness of this performance.

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 4. Carlos Kleiber, Vienna Philharmonic; DG

As I mentioned earlier, Carlos Kleiber had a small performance repertoire, but when he did choose to conduct, it was always at the highest possible level and this performance is no different. From the opening with its sliding intervals, to the bouncing scherzo, and the fourth movement Passacaglia (what other romantic-era composer would have thought to write in that form?) this is a performance that brings Brahms to life. I’ve heard many fine performances of this work, but none better than this one.

CHOPIN: Polonaises. Maurizio Pollini; DG

I’ve been exceptionally fortunate to have seen many of the great pianists perform live, including Vladimir Horowitz, Rudolf Serkin, Alicia de Larrocha, Khatia Buniatishvili, André Watts, Radu Lupu, Vladimir Ashkenazy and – on one occasion – Maurizio Pollini. It was a transcendent experience. Half of his program consisted of music by Chopin and he played as if he were the very embodiment of the composer.

This album of Chopin’s Polonaises is, justifiably, one of Pollini’s most acclaimed recordings. In terms of tempo, dynamics, articulation and the spirit of the music, he seems to get everything right.