There was folk. There was rock and roll. There was blues, coming back home via the 1960s British scene. But thanks to innovative groups like Buffalo Springfield, all those genres merged, glued together against a backdrop of psychedelia. Although the band made only three albums, its influence was undeniable.

At the heart of Buffalo Springfield was the pairing of singer/songwriters Neil Young and Stephen Stills, who had met in 1965 at a folk club called the Fourth Dimension in Thunder Bay, Ontario. They were with different bands at the time and had no plans to collaborate. Fate intervened.

Stills’ band, The Company, broke up, and he moved to California; soon he convinced former bandmate and fellow singer/songwriter Richie Furay to join him there. Meanwhile, still in Canada, Young met bass player Bruce Palmer, and the two of them drove down to Los Angeles in a Pontiac hearse. Things didn’t go great for Young and Palmer, and they decided to give up and head to San Francisco. But before they could leave, they were driving along Sunset Blvd. (in their hearse) and caught sight of Stills and Furay going in the other direction. They all stopped to say hello, and the rest is music history.

Having named themselves after the “Buffalo-Springfield” brand of steamroller parked outside Stills’ house, the band made its debut at the famous Troubadour in West Hollywood in 1966. They had added a drummer: Dewey Martin was a session musician, mainly for country musicians; the manager for the Byrds hooked him up with Stills and company. Those two bands were good friends, and soon Buffalo Springfield hit the road as an opening act on a Byrds tour.

It was still 1966 when a bidding war resulted in a nice deal for Buffalo Springfield with Atlantic Records, specifically for their subsidiary Atco. Their recording career got off to a rocky start with a single that died on the vine (“Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing”) and a debut album, Buffalo Springfield, that had to be released in two different versions before it found its legs. The key factor on the second version was the addition of the song “For What It’s Worth,” which went gold as a single. That song seems at first glance to be an anti-war lyric, although it’s actually about anti-curfew riots in Los Angeles.

Perhaps one of the stumbling blocks for that first album was the use of rookie producers, two men who also served as the band’s managers, Charles Green and Brian Stone. The band complained that the record’s sound didn’t represent the excitement of their live shows, but Atco wasn’t willing to delay release long enough to re-record the album.

Stills and Furay were the main singers on the debut. They share the lead on “Hot Dusty Roads,” written by Stills. It has a funky beat, basic rock and roll harmony, and a country-blues twang in the guitars.

Although Young was not yet participating much as a lead singer, he did compose several songs on that record. Among them is “Do I Have to Come Right Out and Say It?” The smooth-voiced Furay sings lead. Young is already experimenting with psychedelic compositional elements, such as moments of surprising chord changes, a melody that seems to turn randomly, and a floating, ethereal quality in the accompaniment. The chorus of this song, with all the voices in harmony, is an unfortunate example of the underlying weakness of the sound production, just as the band complained about at the time.

The following year, the second album came out, Buffalo Springfield Again. This time, Stills and Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun produced. Given the laundry list of complications, it’s a miracle it got finished. Over the nine months from conception to release, Young quit and rejoined the band multiple times, at one point being replaced by David Crosby. He recorded one of the songs, “Expecting to Fly,” entirely with non-band musicians at a different studio. Meanwhile, Palmer, after several drug-related arrests, was deported to Canada. He sneaked back in illegally to finish the album, but soon gave up on the band altogether.

On a more positive note, Furay tried his hand at composition, creating the country rock tune “A Child’s Claim to Fame,” complete with mountain harmonies like the ones the Everly Brothers had popularized. James Burton, a legend of rockabilly and country (who played guitar for Ricky Nelson, Elvis, and Emmylou Harris among others), plays dobro.

Stills gets the lead vocal and writing credit for “Rock & Roll Woman,” although rumor has it that it grew out of jam sessions with Crosby, who may well have co-written it. Some believe he can be heard in the background vocals, uncredited. Another guest on this song is Doug Hastings, a pioneer of psychedelic guitar. Although it’s not their most famous song, this is one of the distinctive tracks that make Buffalo Springfield Again such an important album.

Another song with a big impact on this record was Stills’ “Bluebird.” It didn’t do particularly well as a single, but through live performances the band turned it into their calling card. The piece has several mini-movements and is unusual for its side-by-side contrasting styles, particularly in the guitars: Stills fingerpicks on an acoustic as Young shreds on an electric. Since Buffalo Springfield was one of the original jam bands of the psychedelic era, and since the song grew and developed over time, it’s appropriate that Atco Records released an extended version of this cut in 1973, long after the band had split.

The band’s members were not being prescient when they called their 1968 album Last Time Around; they had already broken up, and they made the track list from songs they’d previously recorded. Young was already in the band that would become Crazy Horse, and Stills was already working with Crosby and Graham Nash, so they had no interest in continuing the old group. The band’s short existence had been so unsteady that you could say a slow-motion breakup had practically begun just after the band formed. For example, Palmer had been out of the picture for so long that their unreleased tracks barely included him. He plays bass only on the opener, Young’s “On the Way Home.” Jim Messina replaces him on the other songs; he also produced.

That troubled development aside, Last Time Around was well worth the effort to compile and release. There are some excellent songs here, some of which – Furay’s “Kind Woman,” Young’s “On the Way Home” – stuck around in repertoires of the band members’ future groups. Less well known is the Furay and Young R&B-inspired collaboration “It’s So Hard to Wait,” which features a particularly supple vocal by Furay.

Dewey Martin wouldn’t let go of Buffalo Springfield. He attempted to tour with multiple versions of it (New Buffalo Springfield, New Buffalo, Buffalo Springfield Revisited, White Buffalo, Buffalo Springfield Again), a few of which were collaborations with Palmer. Most of them ended after cease-and-desist orders from Young, Stills, or Furay. Palmer died in 2004 and Martin in 2009.

As for Young, Stills, and Furay, they reunited in 2011 for six Buffalo Springfield concerts in California. They started the band, so it’s only right that they should end it together.

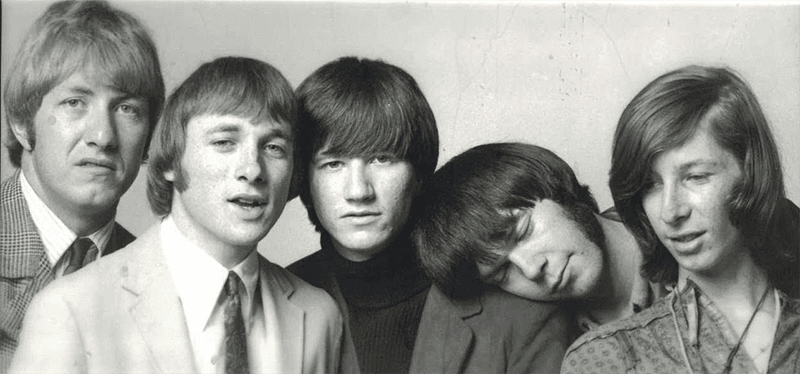

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Atlantic Records/public domain.