In previous installments, this series examined Neumann disk mastering systems, with a brief look at the origin of the LJ Scully LS-76, aka “The Lathe,” in 1976. The introduction of the LS-76, with its very modern low-profile design (euphemism for flat slab) and high-tech automation features, received a very positive reception in the US, which must have acted as a strong incentive for Neumann to proceed likewise.

L.J. Scully LS-76 lathe, serial number 660, at Andrew Hamilton Mastering, Cincinnati, Ohio. Courtesy of Andrew Hamilton.

L.J. Scully LS-76 lathe, serial number 660, at Andrew Hamilton Mastering, Cincinnati, Ohio. Courtesy of Andrew Hamilton.

The Neumann company, inheritors of the German Bauhaus tradition, were not to be outdone on their own playing field! They could make a flat slab better than anyone, and they were determined to prove it! The Neumann VMS-80 and VMS-82 were far more successful than the LS-76, with much better timing and, admittedly, much better marketing.

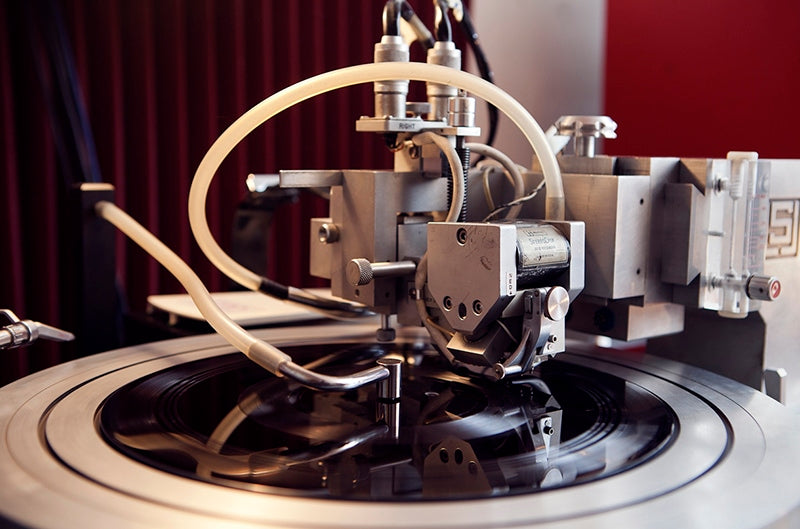

VMS-82 DMM lathe, but converted to cut lacquer using a lacquer suspension box and a Neumann SX-74 cutter head. Courtesy of Scott Hull, Owner/chief engineer, Masterdisk Studios, Peekskill, NY.

VMS-82 DMM lathe, but converted to cut lacquer using a lacquer suspension box and a Neumann SX-74 cutter head. Courtesy of Scott Hull, Owner/chief engineer, Masterdisk Studios, Peekskill, NY.

In the United States, the import of Neumann lathes and their promotion in the industry was handled at the time by Stephen Temmer of Gotham Audio, who many have described as a rather intimidating personality, and who very aggressively and very effectively marketed the Neumann brand and products. Scully, based in Bridgeport, CT, was located right at the epicenter of machine tool development at the time. Larry Scully was already the second generation of the family to become a machinist and lathe designer, taking over from his father, John Scully, the founder of the original Scully company (which had been sold to Dictaphone just before the introduction of the LS-76, which was branded L.J. Scully, the name of the newly-formed company which specialized strictly in the lathe market) and who was the designer of the earlier versions of Scully lathes. John Scully was also reported to be a highly capable machinist. He was reported to have machined and assembled the first Scully lathes entirely on his own, as early as the 1910s!

The doctor is here! Tor Degerstrøm listening for any unwanted noises on his L.J. Scully LS-76 with a stethoscope. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma, courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm at THD Vinyl Mastering.

The doctor is here! Tor Degerstrøm listening for any unwanted noises on his L.J. Scully LS-76 with a stethoscope. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma, courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm at THD Vinyl Mastering.

Their mechanical designs were solidly rooted in the Connecticut tradition of machine tool design. The state of Connecticut has a long history of engineering and implementation of machine tools, from Eli Whitney, Colt's Manufacturing Company, and the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, to the origins of Timex Group USA, Inc., Pratt & Whitney, and various other notable concerns. The town of Bridgeport itself was home to Bridgeport Machines, Inc. (manufacturers of the extremely popular Bridgeport milling machine) and the Moore Special Tool Company, Inc. (run by three generations of the Moore family, producing some of the most accurate machine tools and measurement instruments the world has ever seen), among others.

A 1914 photo of machine gun manufacturing at the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, New Haven, Connecticut.

A 1914 photo of machine gun manufacturing at the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, New Haven, Connecticut.

It would have been hard for the Scully family to not be influenced by this local heritage and culture of quality engineering. Indeed, Scully lathes were always mechanically solid and reliable. I was once called in to repair an older model Scully lathe with a main bearing issue. All it needed was to be adjusted for wear. While at it, I explained to the owner the proper lubrication procedure and its importance. I was shocked to discover that the lathe, which had been operated daily, had NEVER been lubricated at all, or even adjusted, in 15 years of ownership, and still ran!

While the LJ Scully LS-76 was as much of a departure from the original Scully company’s earlier lathes as the Neumann VMS-80 was to Neumann's previous models, it did maintain the same standards as previous machines in its groove pitch computer delay time. All Scully lathes which had such an automation system fitted utilized a 1.0-revolution delay, meaning that the platter would make one revolution between the time the preview head signal reached the groove pitch computer, and the time the program signal reached the cutter head. Scully lathes were also made of aluminum, due to the metal’s favorable sound propagation properties, but this was about the only deviation the lathes had from established machine tool design notions.

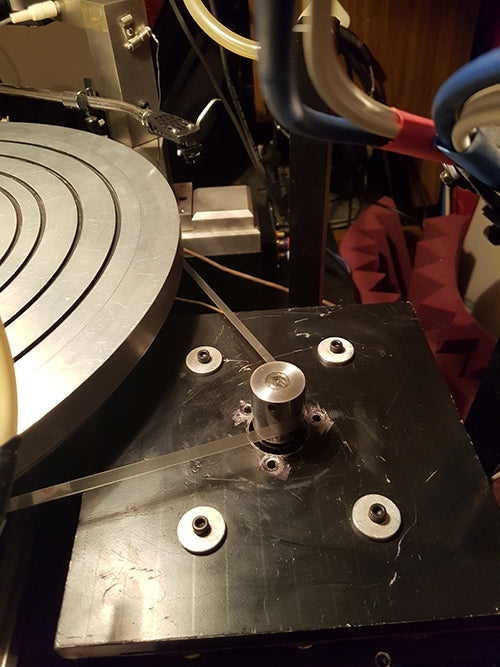

The belt drive system driving the platter of the L.J. Scully LS-76. Courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

The belt drive system driving the platter of the L.J. Scully LS-76. Courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

The LS-76 featured a flat slab bed, departing from the larger and more dominant machine-tool-style beds of the older machines.

Vacuum platter, drive belt and motor on an LJ Scully LS-76 lathe. Courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

Vacuum platter, drive belt and motor on an LJ Scully LS-76 lathe. Courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

Motor, drive belt and vacuum platter on an LJ Scully LS-76 lathe, at THD Mastering, Oslo, Norway. Courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

Motor, drive belt and vacuum platter on an LJ Scully LS-76 lathe, at THD Mastering, Oslo, Norway. Courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.Like all Scully lathes, the platter was belt-driven. The LS-76 was originally offered with a 17-inch vacuum platter, but this was later revised to a 16-inch version. The bearing unit was massive and the 1-inch diameter platter shaft utilized phosphor bronze bearings, supported by a single ball at the bottom. The belt was wrapped directly around the platter rim.

The LS-76 retained the same horizontal slide way concept as the earlier Scully lathes, eliminating the stick-slip behavior of dovetail slideways by means of a rolling-element-bearing "railroad" slideway. (The horizontal slideway on a disk recording lathe advances the carriage, complete with suspension and cutter head, across the rotating record, to cut the spiral groove of the desired pitch. It is worth noting that the lathes of the acoustical recording era, including the earliest Scully lathes made by founder John Scully, advanced the entire platter system under a stationary sound box. This was done for practical reasons, as the huge recording horn was attached to the sound box.) This was similar to how a train rides on the train tracks. Two "tracks" would guide two wheels at the front of the carriage, and a single wheel at the rear would keep it level and moving. This design was very simple, elegant, quiet, and most importantly, required practically zero maintenance. The leadscrew was driven by a single servo motor, controlled by the built-in pitch computer.

Tor Degerstrøm at work with his LJ Scully LS-76. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma, courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

Tor Degerstrøm at work with his LJ Scully LS-76. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma, courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.The 50x magnification Spencer microscope found on older Scully lathes had now been replaced by a 150x Nikon unit, with an output for a video monitor (guess where Neumann got the idea?).

Video monitor displaying the groove structure on disk, as captured by the lathe microscope. Courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

Video monitor displaying the groove structure on disk, as captured by the lathe microscope. Courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.The platter drive system supported speeds down to 16-2/3 rpm, for half-speed mastering, and the cutting of CD-4 disks (the obsolete quadraphonic disk format where the two channels were regarded in the usual manner and the other two were modulated by an ultrasonic carrier and recorded into the same groove, which could only be done at half-speed).

The Westrex 3-D stereophonic cutter head on a Scully LS-76 lathe, with Tor Degerstrøm's hand adjusting the cutting parameters. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma, courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

The Westrex 3-D stereophonic cutter head on a Scully LS-76 lathe, with Tor Degerstrøm's hand adjusting the cutting parameters. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma, courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

The Scully suspension unit was designed to accept either the Westrex cutter heads (commonly used with the earlier Scully lathes) or the Ortofon cutter heads (the Scully brochure for the LS-76 specifically mentions the Ortofon DSS 732 and Ortofon DSS 731 stereophonic cutter heads, one being specifically developed for cutting CD-4 quadraphonic disks, which required an extended high-frequency response for the additional two channels that were encoded above the human hearing range. Scully never developed a cutter head, instead partnering with Westrex for most of the company’s existence, and later moving on to partnering with Ortofon.

The 1.0-revolution delay was an old standard in the US, used by Scully and also by companies offering aftermarket pitch automation systems for Scully lathes (including Capps, who also manufactured disk cutting styli). The preview and program signals were usually derived from a preview-head tape machine, which would commonly be an MCI JH-110M, an Ampex 300, or a Scully 280. Despite Scully's overall reputation and pedigree, and the technological merits of the LS-76, it is perhaps the rarest model of professional mastering lathe ever made on a commercial scale (if a total of around 10 can be considered "commercial scale"!), and rarely used for commercial mastering. If you want to hear the LS-76 in action, Andrew Hamilton of Andrew Hamilton Mastering (Cincinnati, OH), is particularly pleased with the result of his master cuts for Queen City Jubilee by The Slocan Ramblers, a bluegrass band from Toronto. In fact, the band preferred the cuts done using an Ortofon DSS731 cutter head driven by an Ortofon GO741 cutting amplifier on the Scully LS-76 lathe, to DMM cuts done on a Neumann VMS-82 DMM system, which they had already paid for and received from a different facility, so they decided to proceed with Andrews' masters for the pressing. Another one of Andrew’s masters worth looking out for is John Baumann’s Proving Grounds LP, pressed on white vinyl last year. Andrew also informed me that one of his two LS-76 lathes was originally used at Eva-Tone in Florida to cut the masters for their Soundsheets, which were flexi disks that used to be inserted in magazines and even included with cereal boxes. (See Copper’s article on flexi discs in Issue 129.) The other lathe had previously been used at Criteria Studios and later at Fullersound Inc. by Mike Fuller, who had cut, among other albums, Rod Stewart’s Blondes Have More Fun and Kenny Loggins’ “This Is It” (featuring Michael McDonald). Across the pond, Tor Degerstrøm at THD Vinyl Mastering in Oslo, Norway used his LS-76 to good effect in mastering “Are You Land or Water (The Deluge)” by Kitchie Kitchie Ki Me O.

The entire setup at THD Mastering: an L.J. Scully LS-76 lathe, Westrex cutter head, and associated equipment. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma, courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

The entire setup at THD Mastering: an L.J. Scully LS-76 lathe, Westrex cutter head, and associated equipment. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma, courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm/THD Vinyl Mastering.

As with most disk mastering lathes, the Scully LS-76 does lend itself to upgrades and modifications. In common with all Scully lathes, the belt-driven system was often considered a weakness. I have converted many Scully lathes to direct-drive, including an LS-76 which was missing the original drive system. It should be noted, though, that the original LS-76 belt-drive system was a considerable improvement over the belt-drive setup used on the older, "bathtub" Scully lathes. The platter and bearing system was also a great improvement, being much more accurate and requiring very little maintenance in use.

The author looking through the massive platter bearing unit of the L.J. Scully LS-76, with the much smaller bearing unit of the original Neumann/FloKaSon AM44 next to it for comparison. That particular LS-76 was converted to direct-drive by J.I. Agnew. Photo courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

The author looking through the massive platter bearing unit of the L.J. Scully LS-76, with the much smaller bearing unit of the original Neumann/FloKaSon AM44 next to it for comparison. That particular LS-76 was converted to direct-drive by J.I. Agnew. Photo courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.While Scully never entered the cutter head and cutting amplifier market, Scully lathes, and the LS-76 in particular, offered an extremely solid, high-performance mechanical assembly that could be used with any cutter head and cutting amplifier system available. Even though the LS-76 was specifically designed for the Westrex and Ortofon cutter heads, it is a very simple task to machine an adapter plate that would make it possible to fit a Neumann head or anything else ever made, including vintage monophonic cutter heads, if desired. The Scully LS-76 was the peak of lathe development at Scully and, their final design. There is nothing remaining of this operation now. The staff and machinery are all long gone. Fortunately, their lathes were well-made enough to still be in regular use to this day, if they have not fallen victim to one of the many professionals in the audio field who shortsightedly sent disk recording lathes to the scrapyard after a few slow years. With the current resurgence in vinyl and prices for disc-cutting lathes soaring (and all disk mastering facilities in operation currently raking it in and deserving every last cent for their hard work), there is a lesson to be learned here. Never send a perfectly good lathe to the scrapyard. Send it to me instead!

Header image: L.J. Scully LS-76 lathe with Westrex 3-D stereophonic cutter head. The large knurled knob on the front adjusts the depth of cut by means of an “advance ball" system, while the small knurled knob on the side adjusts the lateral position of the advance ball, intended to make it ride exactly where the groove will be cut, depending on the recording pitch. Photo courtesy of Tor Degerstrøm at THD Vinyl Mastering.