Following one of the usual routes taken on several of my road trips, back when I was younger and the world made a bit more sense, our visit to France, covered in the last episode (Issue 176), shall conclude with a drive up north to Calais, from where the Channel Tunnel (also known as the Chunnel), will take us to England.

The Channel Tunnel is a 30-something mile long marvel of engineering, a railway tunnel connecting England to France, running 350 feet below sea level under the Strait of Dover. Special roll-on platform trains are used; you can drive your car onto them and wait in your vehicle for the 20 minutes or so that it takes to cross the channel. There are three types of trains using the Channel Tunnel. One is a standard passenger train that can take you from London to Paris. Another one is the enclosed-platform train for cars, vans and light trucks, and the last type is an open-frame train for heavy trucks. Prior to the construction of the Channel Tunnel, it took a 2-1/2-hour (at best, from Calais to Dover) ferry boat ride to cross the channel, with notoriously bad weather and rough seas over most of the year. I have tried the ferry boat once or twice. But the Channel Tunnel was always my preferred choice for the crossing, despite the much higher cost, as it is a real timesaver. As far as I can remember, I have driven various vintage vehicles across Europe, from its easternmost borders to its westernmost extensions and from the Mediterranean Sea to the North Sea, at least 28 times in the course of running my business.

The Channel Tunnel exits to the surface near Folkestone, with a big sign reminding you that not only is it permitted, but is actually mandatory, to drive on the wrong side of the road. The keen eye will quickly observe that it is an incredibly beautiful country, but cursed with eternally bad weather. Unlike France, in the UK it is very easy to obtain food pretty much anywhere, at any hour of the day or night. Whether you would actually want to eat it is a whole different matter!

The local delicacies include beans on toast, Guinness pie (puff pastry with meat that has the consistency of shoe leather inside, drowned in Guinness beer), fish and chips (Unidentified Fried Objects, possibly fried in used motor oil and traditionally served on used newspaper instead of a plate, although the government has recently imposed stricter “health and safety” regulations that determined that it was the newspaper that was the unhealthy part of this dish), and other gastronomic abominations that will promptly direct anyone still having intact nerve endings on their palate either to the nearest Italian restaurant or straight back to France.

For that purpose, the British automotive industry developed quite a few admirable getaway cars. They ranged from the luxury category of the likes of Aston Martin, Rolls Royce, Bentley, Jaguar and Lotus, to the mid-fi models of Austin Healey, MG, AC, Triumph, Vauxhall, Rover, and others, all the way down to the lawnmower class, erm, sorry, I meant the economy class of Morris, with the Mini being a rather popular example, but unfortunately intended for humans a few sizes smaller than evolution set us up for. Given the narrow roads of Britain, with city planning long predating the notion of a motor vehicle and the rather expensive fuel prices, British vehicles were generally small. There were a few interesting truck manufacturers as well, such as Leyland and Bedford, the latter acquired by General Motors, which introduced a series of vans inspired by 1970s Chevy vans, but equipped with what was essentially a V8 engine cut in half, with only one cylinder bank at 45 degrees to normal, known as the Vauxhall Slant-4. A desperate need to flee to remote and hopefully sunnier parts of the world, along with the adventurer spirit that had turned an island into a large empire, resulted in the Land Rover, a range of sturdy off-road vehicles that found widespread application all around the world, in terrain where few other vehicles would go.

Despite, or maybe because of the bad weather and questionable food, and long before the Channel Tunnel became operational (which greatly sped up the process of escaping in search of better weather and food), England had a long history of innovation and invention in the fields of sound recording and disk recording in particular. Alan Dower Blumlein of London, a prolific inventor, associated with The Gramophone Company and later EMI (Electric and Musical Industries, Hayes, England), had already filed a patent describing a sound recording system that was essentially capable of cutting stereophonic records (with the left and right channels in a single groove, as established and still used to this day), in 1931!

Alan Blumlein, in the meantime, had been busy being contracted to assist the British recording industry in avoiding having to pay royalties for the patents of Western Electric, so apart from his pioneering work in stereophonic sound, he also created a number of monophonic cutter heads. The earliest one made use of magnetic damping and corrective equalization instead of any form of mechanical damping, according to Peter Copeland, an archiving specialist working for the British Library.

Blumlein’s moving coil mono cutter heads, commercially used in EMI (and sub-label) releases, are capable of extending to at least 8 kHz, but were electronically limited to 6 kHz as it was deemed to “sound better” by the powers that be within the EMI organization. In the mid-1940s it appears that the range was extended to 12 kHz, with cutter head improvements.

HMV (His Master’s Voice) also manufactured a range of lathes, cutter heads and cutting amplifiers. The lower-end models were sold commercially, while the high-performance machines were reserved for internal use only. The HMV-branded lathes were produced throughout the 78-RPM era, and not many survive nowadays. They were belt-driven, with guide rods for the overhead carriage and various moving iron cutter heads. They were usually accompanied by beautifully-designed cutting amplifiers. Both the lathes and cutting amplifiers were intended for portable duty, but were insanely heavy for their size, often giving the impression that they are bolted onto the surface they sit on, when in fact they are just heavy.

One of the earliest manufacturers of disk recording equipment in the country was MSS (Marguerite Sound Studios), which made a sturdy and somewhat unusual lathe in the early 1930s.

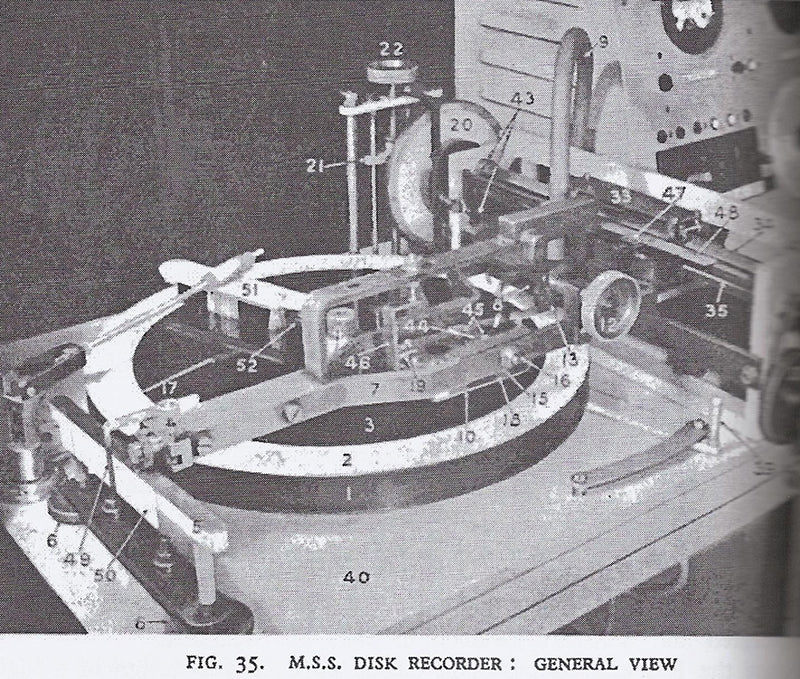

MSS disk recorder. From the BBC Recording Training Manual, 1950.

The MSS lathe had a massive overhead bridge, driven by the same motor that was responsible for driving the platter, through an impressive array of gears, belts, clutches, friction disks and other mechanical contraptions almost certainly inspired by the work of Rube Goldberg. The mechanism offered three turntable speeds and a means to adjust the recording pitch, and well as various levers and hand cranks to engage the various motions and to manually do spirals between the selections on disk, or cut a lead-out groove at the end. It was powered by a fractional horsepower three-phase induction motor. The recording electronics that accompanied the lathe were designed by the BBC. The cutter head was a typical balanced armature moving iron design, with a frequency response extending to approximately 4 kHz.

MSS was also manufacturing blank lacquer disks and eventually expanded to other recording equipment such as tape machines and magnetic tape. The company survived well into the 1960s. During the 1930s, the BBC alone purchased a very significant number of MSS lathes.

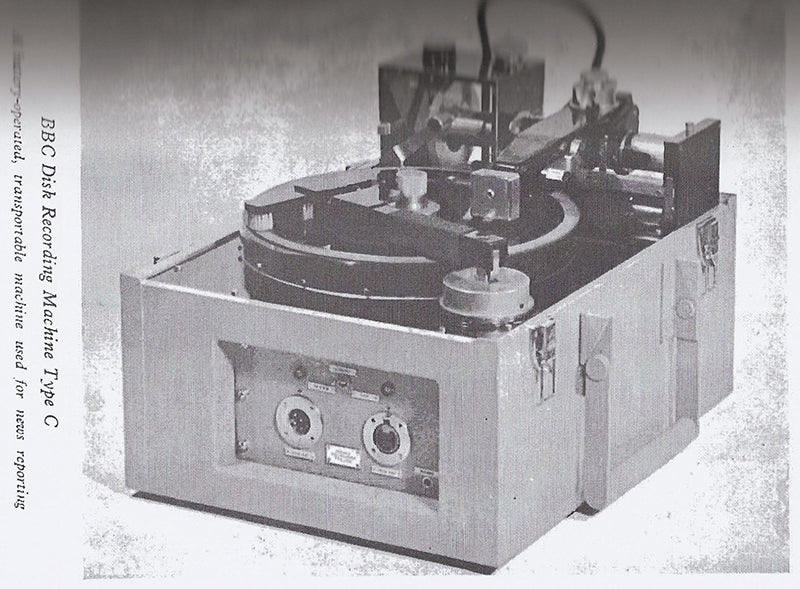

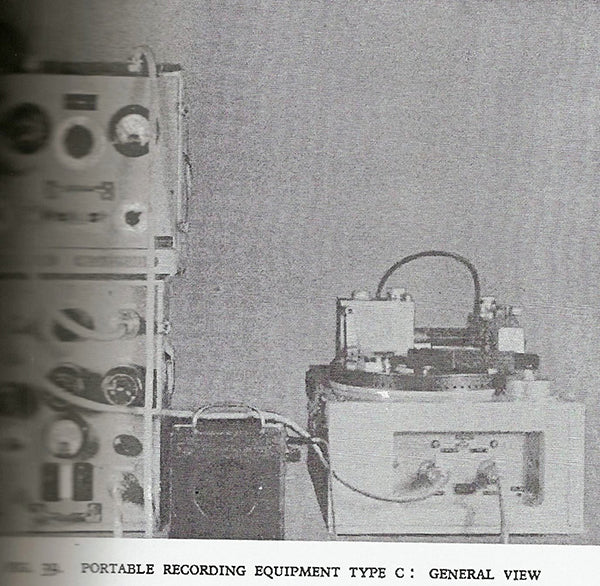

By the late 1930s, the BBC Research Department had developed their own disk recording lathe, known as the “Portable Recording Equipment Type C.” This was a battery-operated machine, with a 12-volt DC motor driving the rim of the turntable. The overhead carriage was driven by a belt from the turntable shaft. It was usually fitted with the Type A cutter head, also of BBC design.

Above images: BBC disk recording machine Type C. From the BBC Recording Training Manual.

In the 1940s, the BBC started importing a large number of Presto lathes from the USA, presumingly because precision metalworking was not their forte. They still remained active in the development of cutting amplifiers and cutter heads, which were outsourced for manufacture. A famous example is the Grampian Type D cutter head, which was a moving iron design, with a second coil wound directly over the drive coil, acting as a feedback coil. Unlike the motional feedback systems used on other cutter heads, this was a unique, transformer-action feedback system. The two coils formed a transformer. The drive coil would set the armature in motion in the usual manner, and the feedback coil would register the core magnetization, including all the magnetic nonlinearities of the core and the back-EMF caused by the armature motion, which caused changes in magnetic reluctance. The resonant frequency was set to 10 kHz and the cutter head was the most inefficient and power-hungry cutter head in existence at the time of its introduction. While the average moving iron cutter head of the time would operate with a 10 – 20 watt amplifier driving it, the Grampian head would need around 150 watts! The most interesting amplifier for the Grampian head did not originate from the UK, however. It was the Gotham PFB-150, designed and manufactured in the US by the importer of the Grampian products at the time.

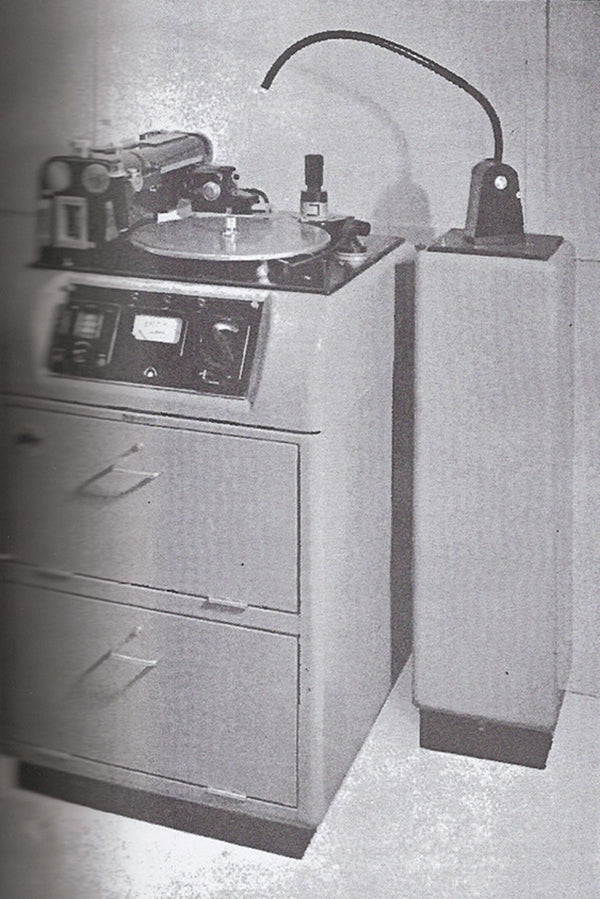

BBC disk recording machine, Type D. From the BBC Recording Training Manual.

Another individual who made lathes in his shed in Yorkshire was Arnold Sugden, who was better known in the high-fidelity world for his Connoisseur brand of turntables. Well, Connoisseur also made lathes and cutter heads, and they were pretty good too!

The Connoisseur lathes were idler-driven by a synchronous motor, and featured a mechanically-variable pitch system, a very interesting feature in its time. Perhaps the most fascinating feature of Sugden’s disk recording system was the use of a moving coil cutter head of his own design, with a frequency response extending to 15 kHz! This was clearly intended for the true Connoisseur!

Above photos: HMV 2300 recording lathe with HMV vacuum tube cutting amplifier. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

Meanwhile, in Birmingham, there was another company manufacturing disk recording lathes. They were called BSR (Birmingham Sound Reproducers and had no connection with BSA (Birmingham Small Arms), other than both being based in what is widely considered to be the most depressing city in Britain, and sharing a similar name). The former primarily made audio equipment, as well as vacuum cleaners and cookware on the side, while the latter made a range of products from rifles to motorbikes.

The BSR Type DR33, introduced in the 1940s, was a portable lathe of solid design. It was belt-driven, with the overhead carriage running on two guide rods with a leadscrew running parallel to them on the same supports, in a manner similar to Fairchild lathes of the same period. The recording pitch was fixed, and a hand crank was provided for making spirals and lead-out grooves. The cutter head was a moving iron design, with the upper range of the frequency response extending to around 5 kHz. BSR also offered a cutting amplifier they called the Type AR15 (not to be confused with the assault rifle of the same designation) and the RBM1 ribbon microphone. BSR was founded in 1932 and folded in 1985, having manufactured a variety of items ranging from laboratory measurement instruments to communications equipment, and of course lathes and turntables (including record changers). They also manufactured tape transport systems which they also sold to other companies, including Bang and Olufsen as a notable example.

By the end of the 1960s, as the disk recording market shrunk with tape recording gaining ground in most applications and with the disk mastering sector essentially divided between two companies (one in the US and one in Germany), there was not much left of the British disk recording lathe manufacturing operations. The British vinyl record manufacturing industry had moved to Neumann and Scully lathes.

All that remains nowadays is the bad weather and the beans on toast, but at least you can now leave easily…well, at least you could, before the Brexit. Oh, well…

Header image: BSR DR-66 disk recording lathe, from original product brochure.