In our previous episode (Issue 161), we discussed the “lightweight” category of monophonic cutter heads made from the 1930s through the 1960s. These moving-iron record-cutting heads, manufactured by RCA, Presto, Rek-O-Kut, Fairchild, Neumann and several others, all range between 5 oz. and 18 oz. in weight. They were lightweight enough to be easily compatible with most disk recording lathe assemblies out there at the time, and, with very few exceptions, they were most often “floated.” This involved suspending the cutter head over the surface of the blank record by means of a spring or a counterweight, or sometimes both. In a floating head system, the depth of cut is set by adjusting the spring height, the spring tension, or the counterweight.

Small variations or irregularities on the surface of the blank disk would cause the cutter head to move up or down, vertically, but the heads would literally ride it out, and the quality of the record cutting would not be affected. Larger disk irregularities, however, would result in an irregular depth of cut. The heavier the cutter head, the more difficult it would be for it to ride out any surface irregularities on the blank.

Western Electric took a different approach to pretty much everything, but especially to cutter head mass, and their method of adjusting the depth of cut. From the early days of electrical audio, Western Electric made some unusually large cutter heads. While on the East Coast of the US and in Europe it was rare for a cutter head to even approach 18 oz., Westrex heads were routinely well above 5 lbs. Many lathes of the time were too small and too weak to handle them. The Western Electric cutter heads usually found refuge in Scully lathes, which were substantially built and could accept pretty much anything one might consider throwing at (or mounting on) them.

The Westrex 2B cutter head on a kitchen scale, to prove the point: It is a heavy beast. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

They sure didn’t do no floatin’ business over at Western Electric.

In fact, if one was to attempt to find the dead opposite of a “floating head,” I don’t believe they would find anything closer than the Western Electric system. The suspension on which Westrex cutter heads were hung still contained a spring, which was adjustable by means of a knob, but this would not set the depth of cut. It would only vary the vertical force applied to the “advance ball” system, which was mounted on the cutter head.

The advance ball assembly on a Westrex 43D cutter head. Courtesy of Tor H. Degerstrøm at THD Vinyl Mastering, Oslo, Norway. Photo by Anja Elmine Basma.

The advance ball was a tiny sphere of a hard material such as sapphire, attached to the end of an adjustable arm. It was placed right next to the cutting stylus and just slightly ahead of it. The cutter head would essentially rest upon that ball, which would ride on the surface of the blank disk, and would ride out irregularities. By adjusting the arm, by means of a large knurled knob located on the front of the cutter head, the relative height of the advance ball would change, allowing the cutting stylus to sink deeper into the blank disk material, or in the opposite direction, withdrawing the stylus from the blank, up to the point where it lifts off completely, and no groove is cut. For a cutter head weighing in excess of 5 lbs., the advance ball system was a simple, effective and reliable way of setting the depth of cut.

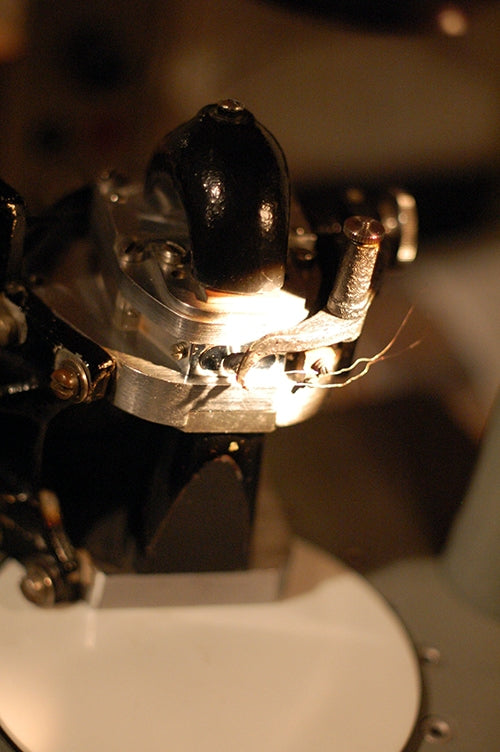

Cutting stylus (made of red ruby), with heater wire wrapped around it, and advance ball (made of clear sapphire), on a Westrex 2B cutter head. it’s modified by the author to accept currently-available cutting styli, as the original Westrex taper shank is no longer available. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

An example of such a cutter head was the Westrex 2B, introduced in 1954 as a replacement for the Westrex 2A, which made its debut in 1948. These were gigantic cutter heads, compared to other monophonic heads of the time. They were a moving-coil design, with a large magnet, and motional feedback generated by a separate feedback coil. The design was elegant and curved, beautifully machined and carefully finished. It is worth noting that back then, there were no CNC machines and no CAD (computer-aided design) software to assist with generating such shapes. The design was drafted on paper, by hand, and subsequently machined using a range of manual machine tools. Each one of these curved parts would require several days of machining to create, using machines that required skilled and experienced humans to operate. After milling the rough shape out of a chunk of metal, several of the parts were then finished on a jig grinder, as evidenced by my investigation of the tool marks under high magnification. During a conversation with Len Horowitz of the History of Recorded Sound (who had also been an employee of Westrex from 1975 to 1995, when he purchased the disk recording division upon the closure of the company’s facilities), he related that several of the intricate parts for Westrex cutter heads were made using what would have most probably been one of the very first commercial uses of electrical discharge machining (EDM), where an electrode accurately removes material from a workpiece submerged in an electrolyte bath.

The elegant curved shapes of the Westrex 2B monophonic motional feedback cutter head. It was far from easy to generate such shapes in the 1940s, before CAD and CNC machines arrived. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

The machining of all the prototypes, as well as all of the parts during the research and development stage for every single Westrex cutter head ever made, was handled by a single individual by the name of Otto Hepp, in-house at Westrex. The actual production thereafter was outsourced to just three machine shops over the entire time span of cutter head manufacturing at Westrex. All three were small, family-run businesses. This offers an indication about how much of a niche market disk recording equipment manufacturing has always been. The whole thing was kept operational by a small handful of very talented and very passionate individuals. Without them, sound recording technology and the concept of high fidelity may have ultimately meant something entirely different. Their dedication to their craft, their determination, and a constant drive for self-improvement is what has presented the world with the gift of high-fidelity recorded sound, and the cultural heritage that has to a certain extent shaped and defined the identity of the Western world of the mid-twentieth century, which the rest of the world embraced and moved towards in large strides.

This cultural ecosystem was rendered possible through an underlying infrastructure of quality manufacturing; a certain work ethic characterized by a desire to achieve significant and challenging goals; a widespread appreciation of the value of education and scientific discourse; and a sense of pride in one’s craft and a desire to pass something down to future generations, not least as a contribution to the collective body of human creation and knowledge, which is a prerequisite for further development. The aforementioned was also a significant contributing factor to securing the economic conditions prevalent in the parts of the world where it was possible to expend time and resources in activities not directly essential for basic survival. In these times of rapid change and disruption, it is important for older generations to remember and for younger generations to discover what it took to reach the present state of cultural and technological advancement. Over a relatively brief span in the middle of the 20th century, we put men on the Moon; connected the world with telecommunications that led to the development of the internet; put large fins on motor vehicles powered by impressive motors and made it possible for the average person to drive to work or take a family trip in them; improved the average quality of life at home, at work and in our communities, and significantly furthered all the ‘graphys,” from typography and photography to phonography/discography.

Automotive design has always reflected the prevailing mood of the time. Bright colors, design statements, luxurious and comfortable interiors, generous dimensions, and powerful V8 engines were indicative of a general mood of optimism, self-confidence and prosperity. It acted as an incentive for what your hard work could bring home. This culture was reflected in the music and film industry of the time and was influential in the development of the high-fidelity audio scene. To quote Jeremy Clarkson, “nobody puts fins like that on a car unless they are pretty sure of themselves!” In 1958, Westrex entered the stereophonic era and introduced the 3A cutter head, which, in adherence to company policy (or perhaps just tradition) was still bigger and heavier than anyone else’s cutter head. There was never anyone or anything out there that could challenge Westrex cutter heads in terms of size and weight, although Fairchild’s commendable efforts to this effect resulted in their 642 stereophonic cutter head. Every bit as heavy as the Westrex cutter heads and also equipped with an advance ball system, the bizarre Fairchild 642 was unfortunately nowhere near as successful in the market. The 3A was succeeded by the 3B and later the 3C, with a total of around 50 units being made, all three models counted in. These were produced up until the highly successful Westrex 3D was introduced in 1964. In disk-recording terms, highly successful translates to around 250 units made in total, including all the variants of the 3D, over the course of 30 years. Courtesy of Pexels.com/Mike van Schoonderwalt.

Interestingly, while the competition was introducing solid-state cutting amplifiers, Westrex held on to their vacuum-tube RA-1500 Series (such as the RA-1541 and its variants) cutting electronics for way longer than anyone else, well into the solid-state era. According to one of their research papers published in the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society at the time, this choice was explained by the fact that many of these systems were purchased in countries where the transistor had not yet arrived. As a result, it was much simpler for engineers in those countries to do any field repairs and maintenance on familiar vacuum tube electronics, rather than having to deal with technology they had never before encountered, and where they would not be able to find repair components in their local markets. While the solid-state 1700 Series cutting amplifiers are more commonly encountered nowadays, the vacuum-tube 1500 Series are more highly regarded for their sound and fetch a premium on the second-hand market, if they can be found at all.

All the Westrex cutter heads were equipped with an advance ball system, and the tradition continued into the stereophonic era. However, it was also possible to float them, and there was an aftermarket suspension unit developed at A&M Records that specifically designed to float the Westrex 3D cutter head.

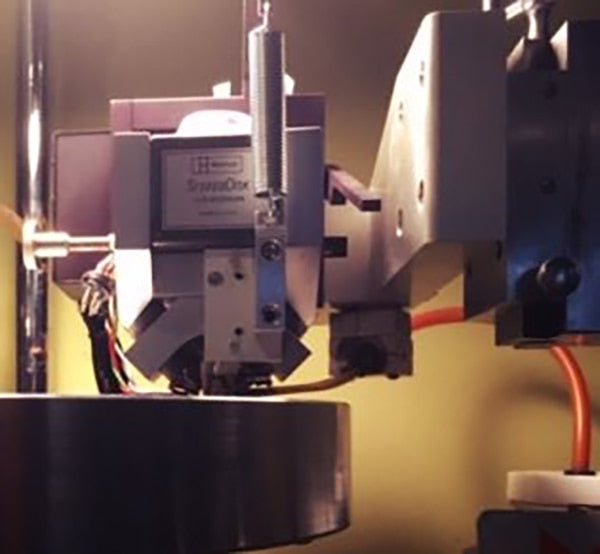

The Westrex 3D stereophonic cutter head being floated, with the advance ball assembly removed. It is held on an A&M suspension unit on a Scully disk mastering lathe, with heavy modifications. Courtesy of Eric Conn, Independent Mastering, Nashville, Tennessee, https://independentmastering.com.

Meanwhile, in Europe, Neumann and Ortofon were developing stereophonic cutter heads which were smaller and lighter, with no provision for an advance ball system. These heads were always floated, and this tradition persisted up until the end of disk-recording equipment development and manufacturing in Europe in the late 1980s.

In the next episode, we will discuss the pros and cons of floating a head versus using an advance ball system.

Header image: advance ball and stylus assembly on a Westrex 2B cutter head, repaired and modified by the author. The wires wrap directly around the red ruby stylus are for “hot stylus” recording.

Previous installments in this series appeared in Issues 161, 160, 159, 158, 157, 156, 155, 154, 153, 152, and 151.

0 comments