I first heard about the University of Rhode Island Guitar Festival during our annual fall trip to Narragansett in 2021. My wife and I like to make one final visit to shore when sunbathers are replaced by leaf-peepers and fishermen, and crowded sunny beaches transform into misty cold seascapes. So, it was a surprise to find our seaside motel filled with guests from all over the Northeast. We figured there was a wedding in town until a man in the next room mentioned a guitar festival at the URI campus just 15 minutes away in South Kingston. The festival was almost over by the time we got there, but we vowed to come back in 2022.

At first, I imagined the festival was going to be like Guitar Center on a Saturday afternoon before Christmas, full of burgeoning rockers shredding on the latest electric guitar gear. Maybe it would be equal parts concert, clinic, and retail bonanza. Anyway, I hoped there would be some interesting guitars. I remember seeing Aerosmith many decades ago and Joe Perry played a 10-string BC Rich “Rich Bich” with double the D, G, B, and E strings and four corresponding tuning pegs on the body of the guitar. Coincidentally, Bernardo Chavez Rico had started out building classical and flamenco guitars with his father before launching the visually unique B.C. Rich line of electric guitars. Speaking of iconic instruments, I love Jimmy Page’s double neck Gibson EDS-1275 – the one that looks like two Gibson SGs smushed together, a 12-string on top and the six-string below. That’s the one Jimmy uses for “Stairway to Heaven” in the film The Song Remains the Same. We all know the acoustic guitar figures prominently in the studio version of “Stairway to Heaven” – like the first five minutes – but Jimmy plays all the parts magnificently on his double neck. While the acoustic adds sparkle and tension before the solo, I don’t miss the Harmony Sovereign H1260 used in the studio version.

That’s how I generally think of acoustic guitars, as a prelude or background to the heavier stuff like Heart’s “Crazy on You,” The Who’s “Pinball Wizard,” Jimi Hendrix’s version of “All Along the Watchtower,” and a host of other hard rock songs. Otherwise, they’re the domain of people like James Taylor, Johnny Cash, and Joni Mitchell.

But there is a place where acoustic guitar exists all on its own, with absolutely no need for singers or accompaniments. The URI Guitar Festival has nothing to do with Jimmy Page playing a 1970s double neck and everything to do with Andres Segovia playing a 1912 Manuel Ramirez (currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). Although the 2022 festival expanded into other plucked instruments, including the oud (pronounced ood), mandolin, and harp, there were no B.C. Rich or Gibson guitars. The festival is the realm of specialized luthiers like Juan Oscar Azaret, Stephan Connor, and Chapman & Fisher, to name just a few out of scores in the US.

Before the festival, I thought all acoustic guitars were basically the same – given their common origin. Today’s guitar evolved from the Renaissance-era Spanish lute known as the vihuela, which is still used to play mariachi and early European music. In the mid-1850s, luthier Antonio de Torres Jurado (1817 – 1892) developed what would become the standard for the earliest classical guitar and the forerunner of modern steel-string acoustic guitar. However, the classical guitar adheres to its historical traditions and expresses its differences through design, learning method, and playing technique.

The most important difference is that a classical guitar is built to accommodate only nylon or polymer strings, replacing the original animal gut and silk. (Technically, nylon strings are made from pure nylon for the E, B and G strings, and a nylon core with a steel wrap for the D, A and E strings.) A classical guitar usually has a figure-eight shape with a pronounced waist, distinguishing it from some of the acoustic models we might recognize, such as the familiar Martin D-35 “dreadnought” played by everyone from Judy Collins, Elvis Presley, and Johnny Cash to Pete Townshend, David Gilmour, and Bruce Springsteen. Furthermore, a classical guitar has a wider neck, more space between the strings, no position markers on the fretboard, and is played seated with a footstool instead of strap for support. Plucking and strumming is done with long fingernails or calluses instead of a plectrum (pick).

Adrian Montero, a Master’s degree student in classical guitar performance at URI, during a seminar. Courtesy of Tom Methans.

One of the many educational seminars at the festival. Courtesy of Tom Methans.

To avoid confusion, the classical guitar, also called the Spanish guitar, is not the same as a flamenco guitar. The latter is lighter, thinner, and has strings closer to the body for easier tapping. It has clear, quick, loud, bright notes with short sustain and a slight buzzing sound. The flamenco guitar often accompanies a troupe and must be heard through singing, clapping, castanets, and the stomps of the flamenco dancer’s nail-studded shoes. Though the classical guitar may be included in string and chamber music ensembles, it really shines as a solo instrument. As Beethoven said, “The guitar is a miniature orchestra in itself.”

The other major difference is how one learns to play classical guitar. I’m sure there are exceptions for prodigies, but it is not a DIY-punk or self-taught process based on three chords. In order to interpret the old masters like Fernando Sor, Francisco Tárrega, and Agustín Barrios, years of formal study are required in programs offered by universities like the University of Rhode Island, not to mention private instruction and international competitions on a path to a career of teaching, recording, and performing.

With lectures, presentations, and master classes included in the ticket price, the URI festival provides a small glimpse of what it takes to play this amazing instrument. I attended a technique class by René Izquierdo, who discussed guitar ergonomics and demonstrated warm-up routines and the best positions for effective playing. If you’ve ever watched a classical guitarist, you might have noticed their posture and the angle of their guitar neck lined up close to the shoulder on the fretting arm. There are reasons for that. Try this exercise at home: sit perfectly upright and use a guitar, tennis racket, or mimic the position with your fretting hand at a 45-degree angle between your knee and head. Note how your wrist and shoulders feel. Then, move the guitar into a horizontal position and feel how the tension in your fingers, wrist, and shoulder change on the fretting arm. Did it also affect the range of motion in your strumming arm? Now, hunch over the guitar and crane your neck so you can see what your hands are doing. Has your breathing capacity decreased dramatically? Finally, go back to the original posture and notice how much better you feel, and how much easier it is to play with the fretboard and strings in full view. Hence, the point of Izquierdo’s lesson for new learners.

René Izquierdo. Courtesy of Marian Goldsmith.

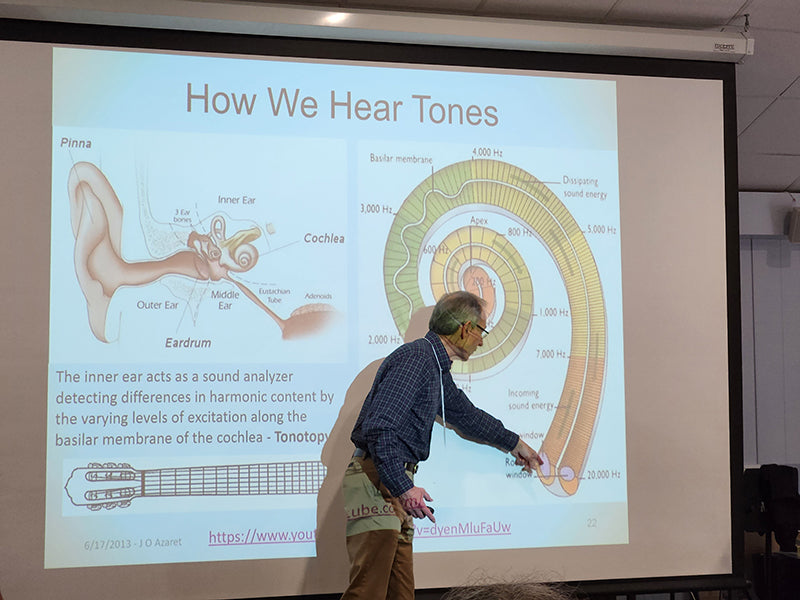

Next was a presentation by Juan Oscar Azaret, a luthier, engineer, and physics professor who worked at Bell Laboratories for many years. As an engineer and physicist, he understands the science behind sound and acoustics. Azaret performed a few Chladni tests showing the vibration patterns on a guitar’s soundboard and, with an oversized motorized string, he demonstrated what the string vibrations look like at certain notes, i.e. the number of Hertz. He then showed us how bracing patterns on the back of the guitar impact sound by demonstrating three instruments inspired by historic builders: Ignacio Fleta (1897 – 1977), Jose Luis Romanillos (1932 – 2022), and Michael Kasha (1920 – 2013). The students in the room remarked on the noticeably different tones and discussed which guitar designs were better for particular compositions and performance styles. Never before have I been able to appreciate the sound and nuance of a classical guitar played live in a room, let alone from three different bracing designs.

The final part of the morning session was a workshop with Simón Shaheen playing the oud (pronounced ood), a fretless pear-shape lute with a short neck and five couplets of strings plus a bass string. It is related to similar instruments found in Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, and produces mesmerizing, complex, and layered Arabic music timed to 10 beats per measure. Simon Shaheen is a touring musician and instructor at the Berklee School of Music, Princeton, Columbia, and Julliard. If you have a streaming service, check out his band Qantara.

Juan Oscar Azaret tap-testing the soundboard of a guitar. Courtesy of Marian Goldsmith.

Simón Shaheen playing the oud. Courtesy of Marian Goldsmith.

The rest of the day was scheduled with a master class, recitals by young performers vying for scholarships and prizes, and an evening concert featuring a string ensemble, Simon Shaheen on oud, and guitarist Andy McKee, with performances on acoustic and baritone guitars. Organizing and planning this Herculean event is Adam Levin, a classical guitar professor at URI, artistic director for the URI Guitar Festival, and a busy performer. He started the event in 2015 and has consistently increased attendance to its current fully-packed four days of education and performances. Next October will mark the eighth year of the Festival: the dates for 2023 are October 18 – 22, and you can start buying tickets as soon as July 1 of next year. For music lovers, being immersed in classical guitar is a great excuse to spend a fall weekend in New England. Moreover, Rhode Island is a year-round destination, with plenty of places to stay and eat near the campus. If you enjoy craft beers, there are a several breweries within a short drive of URI. My current favorite is Whalers.

Andy McKee. Courtesy of Simone Cecchetti.

Duo Sonidos: Adam Levin, guitar, and William Knuth, violin. Courtesy of Marian Goldsmith.

Andrea Gonzalez Caballero. Courtesy of Marian Goldsmith.

The Great Necks Guitar Trio. Courtesy of Marian Goldsmith.

Header image: Chinnawat Themkumkwun, courtesy of Marian Goldsmith.

0 comments