I just received my reel-to-reel tape copy of Jazz at the Pawnshop from AudioNautes Recordings last week. For those of you who are unfamiliar with this recording, who I suspect will be very few, I will outline its origin. This is a live recording made over two days in December 1976 at the Jazzpuben Stampen (meaning pawnshop in Swedish) in Stockholm of a six-piece jazz band consisting of alto saxophone, clarinet, piano, vibraphone, drums and bass. The recording was made by the independent Swedish record label Proprius, on two Nagra IV-S portable tape recorders with 2-track, 1/4-inch tape running at 15 ips. Nagramaster equalization was used, with Dolby A noise reduction. Neumann U47, M49 and KM56 microphones were employed, and mixed to stereo in real time on a Studer mixer. This is almost the exact same set up that my team has been using to make live recordings for the past 20 years, except we do not use noise reduction.

The Nagramaster equalization places the high frequency transition at 11.8 kHz, which is more than one octave above the more common IEC/CCIR equalization. This means that during playback, the high frequencies are not boosted until well beyond the tape hiss frequencies, but at the expense of reduced headroom. Recordings made with this EQ therefore have less noticeable tape hiss.

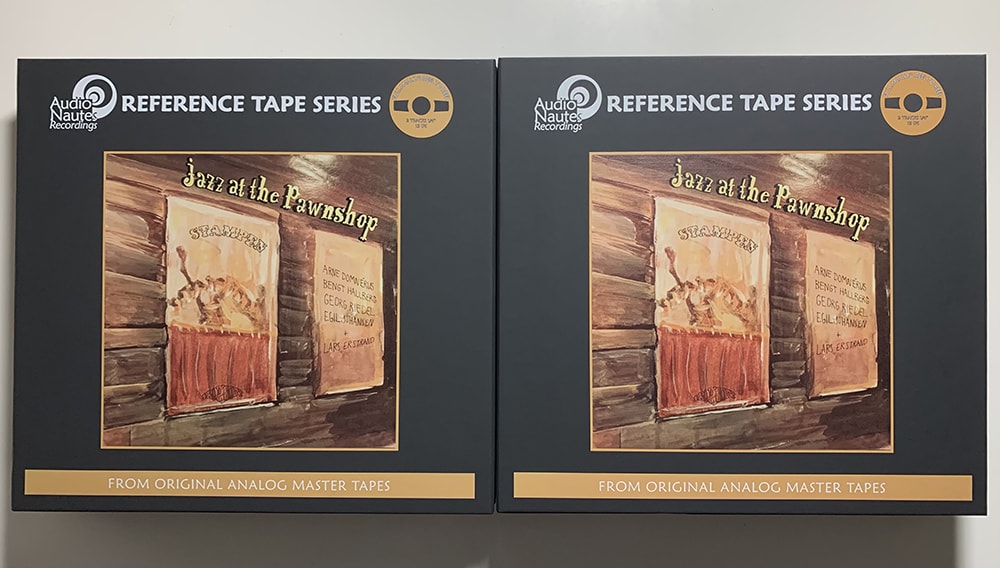

Jazz at the Pawnshop was originally released as a double-LP in 1977. For the US market, the LPs were cut at half-speed and pressed at JVC in Japan, and distributed by AudioSource. This is the LP version that I bought on its initial release. The recording was immediately lauded by hi-fi magazines and audiophiles and has become a standard for equipment demos in showrooms and audio shows. Jazz at the Pawnshop has been reissued in almost every format imaginable, and 58 versions are listed on Discogs. The latest version available is on 1/4-inch, 2-track, 15 ips tape, and is the subject of this review.

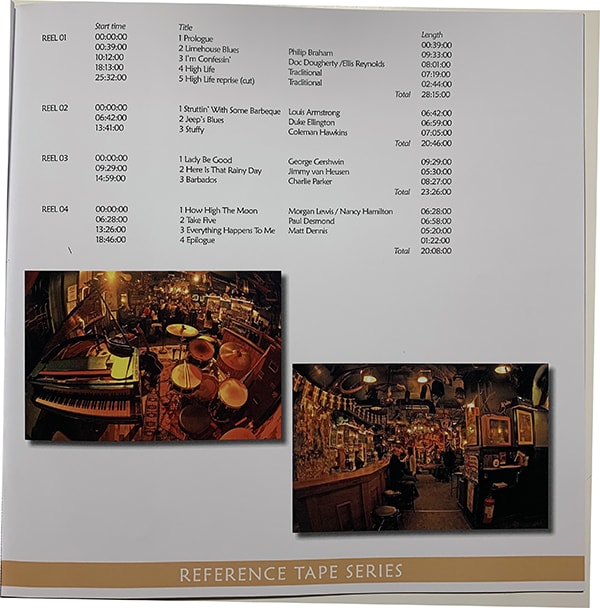

Jazz at the Pawnshop contents.

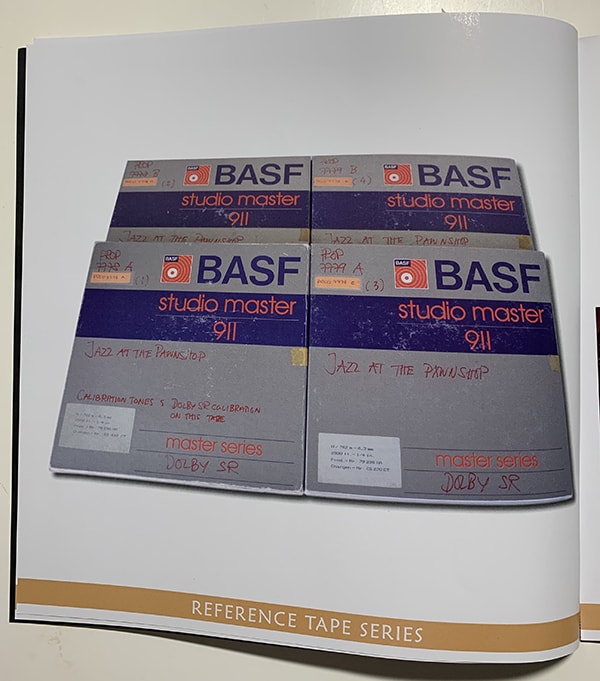

AudioNautes is an Italian company that reissues recordings on LP and digital formats. They have already reissued several Proprius recordings, and this year they got into the tape format for the first time with another well-known Proprius release, Cantate Domino. Proprius sent AudioNautes the original session masters. The use of these original tapes is becoming increasingly rare, as we have learned from the latest Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab controversy. There is usually only one session master in existence, unless several tape recorders were used in parallel during the recording session (we always run two Nagras in parallel). Editing was often done directly on this tape, and therefore a genuine edited session master (called an edited work part) should have many splices. Record labels would make production masters off the edited work part to be used for cutting LPs, making cassettes and CDs, and as backup copies. The original master is then locked away and rarely touched again.

After a number of years, the splices on the session master would have become fragile and often needed repairing. These session tapes therefore need to be handled with great care. Some of these recordings were made on tapes that turned out to suffer from sticky-shed syndrome, where the magnetic oxide particles that hold the recorded signal fall off from the tape backing. Tapes in this condition need to be baked at a precise temperature to drive off the moisture before they can be played, and there are only a limited number of times one can do this. Prying these masters out of the hands of the record labels is therefore a big deal.

According to Fabio Camorani, the owner of AudioNautes, a straight 1:1 safety master was first copied from the session tapes, as stipulated by his contract with Proprius. The safety master was analyzed to identify any problems on the session tapes that required attention. A production master was then made from the session tapes, using the minimum amount of manipulation necessary to correct the problems. Customers’ tapes are produced by copying from the production master one by one, using two directly-connected Otari MTR-15 professional tape machines.

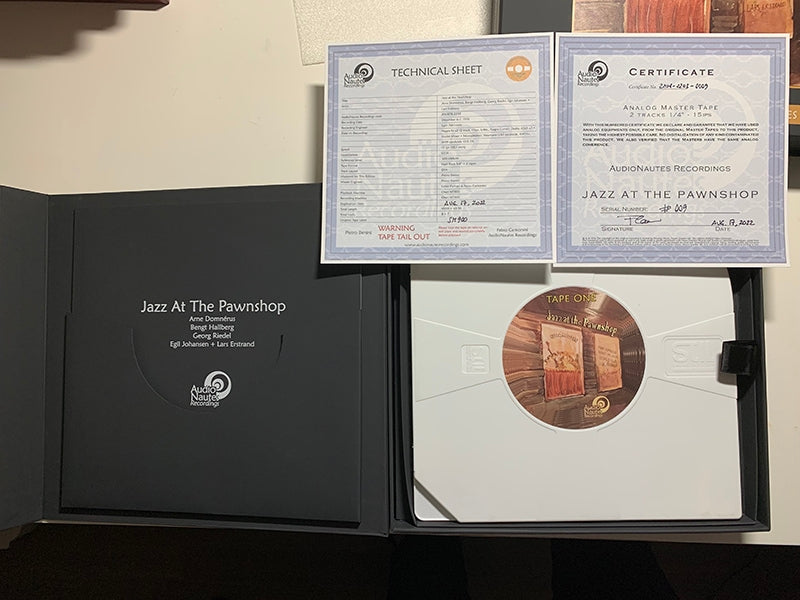

One of the reels of the Jazz at the Pawnshop set.

The packaging of this reissue is in my opinion the best of all the commercial tapes I own, as befitting the reissue’s Italian origin and price (€1,340 directly from AudioNautes). Jazz at the Pawnshop comes in two large boxes with a beautifully-printed reproduction of the album cover in front. Each box contains two reels, each reel placed in its own plastic casing from STIL. Each reel contains the full 33 minutes (2,500 feet or 762 meters) of tape, even though a couple of the reels contain only 20 minutes of music. That means a bit more winding and rewinding, but it makes the product look more uniform and professional.

There is a technical sheet giving details of the recording as well as the duplication, and a certificate of authenticity. A booklet outlines the background of the recording and the technical details of the production of the tapes. Photographs of the venue and the band members are also included. The high-output SM900 studio tape from RTM is used with custom metal reels that are laser-etched with the title and the individual serial number. My set has a serial number of 009, and the contract with Proprius does not limit the number of copies that can be made, even though Fabio might call it a day after he has produced a certain number of copies.

I don’t remember ever sitting down to listen through the whole album in the past for the purpose of evaluating the quality of the sound and music, even though I must have heard Jazz at the Pawnshop reproduced in more systems than any other, given its ubiquity in showrooms and demonstrations at one time. Doing so now is quite revelatory. I started with the AudioNautes tapes, played on my Nagra T Audio tape machine with the playback head wired directly to my DIY balanced tube tape head preamp. I should note that I recently modified the equalization circuit of the preamp. Previously, I used a latching relay to switch between the different available EQs. As I use CCIR/IEC 99 percent of the time, I have decided to hardwire the components directly to avoid passing the signal through the magnetized switch. I only need to re-solder a wire in each channel if I want to change the EQ. I also replaced the trim pots in the EQ circuit with precision metal foil resistors, since the frequency response has remained very stable over time.

Just a few minutes into the first reel, what struck me was the scale of the sound. The soundstage is wide and deep, with the wind instruments placed upfront. The result is very impressive, as if you are sitting just off the front edge of the stage. There is no audible tape hiss at my usual listening volume, as expected from an early-generation master tape copy. The sound is extremely alive, with highly realistic dynamics. Even though the recording is upfront in perspective, there is no harshness, which can be especially problematic with saxophones and trumpets. The drum and piano solos are rendered with jaw-dropping realism. The transient and dynamic impact and the reverberation sound completely natural, one of the areas where analog has an advantage over digital.

The master tapes for Jazz at the Pawnshop, from the set’s booklet.

Information from the set’s booklet.

The piano, in particular, has a weight and solidity that is rare in recordings, a reach-out-and-touch realism. The sound of the vibraphone is crystalline with a roundness of tone that reflects the material the ends of the mallets are made from. The imaging is superb, with each note occupying its space in the air in all its three-dimensional splendor. The music is fun, played with enthusiasm and verve, even though it breaks no new ground. This is not the kind of demonstration record that one has a hard time sitting through. Now that the overdose from 30-odd years ago has dissipated, I will be more than happy to come back to it from time to time for pure musical enjoyment.

After going through all four tapes, I moved on to the original LPs. They are still in pristine condition since I bought them new and have only played them a few times. I gave them a wash in my Degritter ultrasonic cleaner, and then played them on my Classic Turntable Company-modified Garrard 301 turntable. I use a 12-inch tonearm built by a German gentleman called Alfred Bokrand, based on the original Ortofon AS-212 but with new bearings, brass counterweights ,and a banana-shaped aluminum arm tube. This arm has the lowest distortion of any pivoted arm I have encountered, and has better low-frequency extension and power than my SME 3012. The cartridge is an Ikeda 9TT, and the phono preamp is of the same design as my tape-head preamp, with the same complement of NOS tubes.

I must say the LPs sound very impressive also. The scale is a little smaller than the tape. The LPs seem to have a bit more high-frequency energy, which could be down to the mastering, or perhaps the session master has lost some high frequencies with age. The most obvious difference is in the weight and solidity of the piano. While still very impactful, it lacks the reach-out-and-touch quality I hear on the tape. The drums, too, are just that little bit less dynamic than on tape, something one would not notice without a back-to-back comparison.

Analog tape has this naturalness and flow that is hard to find on LPs, usually only present on direct-to-disc recordings. The sound of this tape has more density, more saturated tone color, and more life-like dynamics compared to the original LPs. The whole process of LP mastering and manufacturing, no matter how well done, will compromise the sound quality to some degree. A direct copy from the original master tape is going to get you as close as possible to the recording session, unless you have the resources to buy the record label (as the Hong Kong-based owner of Naxos, Klaus Heymann, has done) and get your hands on the original masters. But even if you do, would you be willing to play these ancient and precious tapes repeatedly? Record labels are increasingly reluctant to grant access to their master tape collection, which means the window of opportunity to own copies of genuine master tapes might soon close altogether. Anyone who enjoys Jazz at the Pawnshop should therefore seriously consider investing in this set of beautifully-produced tapes.