Meeting one’s musical heroes can often take place in unexpected circumstances. Back in the late 1980s, a particular music hero of mine had played a rare concert at the Beacon Theater in Manhattan. On top of the incredible musical performance, which ran the gamut from techno pop, world beat, classical and funk to avant-garde, it was my first music date with the woman whom I would eventually marry.

A year later, I actually saw him in the lobby of my apartment building with his son, dressed casually wearing a Yankees cap. I told him I was a big fan of his and loved the Beacon show. He was gracious and humble and thanked me for the compliment. I then asked him how long he was staying in New York.

He said, “I’m living here now.”

I said, “Wow, that’s great.” Thinking he was closer to midtown, where many of the Japanese companies like Sony had offices, I asked, “did you find someplace in midtown?”

He chuckled. “No. I live here now. 11th floor.”

My jaw almost hit the floor. The elevator opened and we went inside.

“Wow. Guess we’re neighbors.”

“Yes. Enjoy the day,” he said as I got off on the 4th floor and the elevator doors closed behind me. That was my first personal encounter with the legendary Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Japanese techno-pop rock Icon. EDM/cyberpunk music pioneer. Fashion model. Movie star. Academy Award-winning film composer. World/ethnic music fusion collaborator. Synthesizer and computer music tech guru. Solo piano recording artist. Musical ambassador. Activist.

These are just a few of the titles that describe Ryuichi Sakamoto.

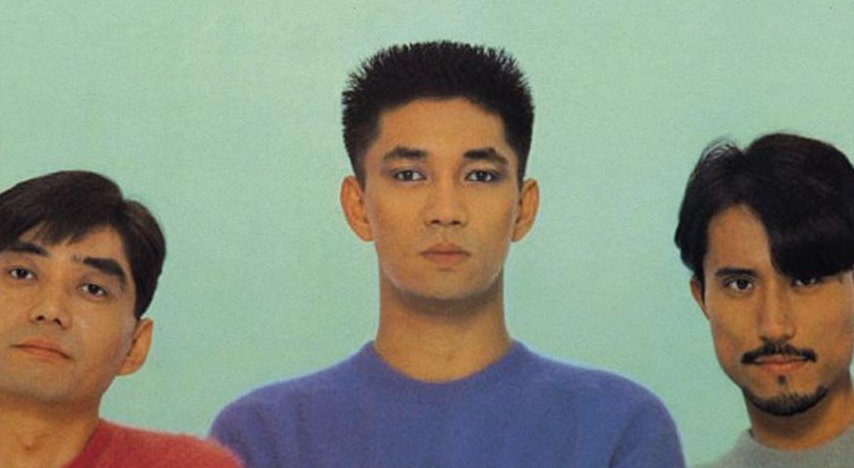

A classically trained pianist in Japan, Sakamoto first rose to prominence as a solo instrumental synthesizer/keyboard artist in the late 1970’s with his first release, Thousand Knives of Ryuichi Sakamoto. His collaborator on drums, Yukihiro Takahashi, was a former member of The Sadistic Mika Band, the first Japanese band to sign with a US record label (Harvest/EMI) and tour with a major UK rock act (Roxy Music). With Haruomi Hosono on bass, the trio formed Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO), which became one of Japan’s all-time best-selling music acts and the first Japanese band to chart on Billboard, successfully sell records, and tour worldwide.

Yellow Magic Orchestra: Putting Original Japanese Music on the International Map

While Sakamoto’s male-model good looks made him a pop idol heartthrob in YMO, his role in the band was actually equal to, if not originally subordinate to drummer/lead vocalist Takahashi and bassist/visionary Hosono. The concept of “Yellow Magic,” the incorporation of traditional Japanese and Chinese music, and the use of Syndrums (the first commercially available electronic drums) and drum machines, as well as being one of the first groups in history to use digital sampling – came from Hosono and his previous studio work with international fusion artists such as Osamu Kitajima. In fact, YMO was originally named, Harry Hosono and the Yellow Magic Band. Hosono’s Happy End was one of the first Japanese rock bands in the late 1960s to focus on original music in Japanese. His next group, Tin Pan Alley, combined R&B and jazz with elements of traditional Hawaiian and Okinawan music. Ironically, Hosono’s initial concept of YMO was that it would be a one-off project combining disco, electronic music, and subversive takes on Western notions of Asian exotica.

Takahashi, the drummer for the groundbreaking Sadistic Mika Band, brought his rock and glam rock sensibilities to YMO, as well as versatile percussion skills and excellent vocals in both Japanese and English. He was also the most accomplished commercial pop songwriter of the trio. Hosono ultimately decided on Takahashi because he was one of the few drummers in Japan who was sufficiently skilled to play actual drums in tight sync with drum machines, something even ace drummers such as Toto’s Jeff Porcaro and the Who’s Keith Moon struggled with, due to the lack of an interactive groove in quantized electronic music of the era.

YMO’s solution to literally “program” a groove into a sequencer was groundbreaking (details below).

(Note: while playing in sync with other programmed percussion today is standard, it was still a very new phenomenon in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The legendary Al Schmitt, who engineered Toto’s hit song “Africa” has stated in interviews that the drum track recorded by Porcaro was actually a huge four-bar analog tape loop that literally was strung across mic stands to take up the slack. Porcaro’s frustration with being able to consistently match the precision required for the drum part prompted this unique workaround.)

With his extensive classical background and keen interest in world music combined with his early Moog, ARP and Buchla synthesizer experiments and research, Sakamoto brought a level of formal Western musicianship gravitas to the party. It was Sakamoto’s interest in fellow electronic music pioneers Kraftwerk that gave YMO the impetus for incorporating its synth and electronic music foundation into a dance music format, albeit with a lighter touch than the synth pioneer’s Teutonic robotic approach and with a stronger dose of Japanese pop and melody influences. Hosono realized the emphasis on instrumental music to appeal to discos and DJs would bridge the language gap, while incorporating visual and aesthetic elements from acts like Devo would help sell the YMO image abroad.

YMO’s hit song, “Computer Game/Firecracker” became a DJ favorite and broke into the Billboard UK (#17) and US (#60) charts.

While it is commonplace in hip-hop and rock today, the co-mingling of music, media and corporate industries is still a relatively recent phenomenon. Lacking the rebel anti-corporate attitude from the 1960s that fueled US and UK rock and pop music, the Japanese music and entertainment industries have long worked collaboratively with mainstream businesses. YMO scored early deals with Japanese corporations like Fuji (tape) for promoting electronics products, as well as creating original music for jingles and other ads – something unfathomable at the time for their contemporaries in the West.

Their 1979 single “Rydeen,” from YMO’s, Solid State Survivor LP has often been used as a video game and ringtone sample for its epic theme song feel.

“Rydeen” was coincidentally also the name of one of the giant robot heroes from the anime inspired cartoon series, Shogun Warriors. Rydeen was a giant robot that could change into an eagle-shaped aircraft. One of the first giant robot teams to tie in with toys (licensed by Mattel) and comics (Marvel Comics), Shogun Warriors was the historical precursor to the popular Transformers series in concept, imagery and marketing.

Another single, Behind the Mask, began as a Ryuichi Sakamoto composed jingle for a Seiko wristwatch commercial. With English lyrics by Chris Mosdell, Behind the Mask would become one of YMO’s most famously covered tunes, including versions by Michael Jackson and Eric Clapton.

By 1983, international respect for YMO’s musicianship was acknowledged from artists like Duran Duran, Thomas Dolby, the Human League, Afrika Bambaataa, Depeche Mode, Todd Rundgren, Gary Numan, Japan (whose lead singer, David Sylvian, would go on to collaborate frequently with Sakamoto on their respective solo work), and the eccentric DIY recording pioneer, guitar virtuoso and former leader of Be-Bop Deluxe, Bill Nelson. Nelson became the first non-Japanese musician to perform on a YMO record, playing lead guitar on their album Naughty Boys. Nelson’s guitar can be heard on numerous solo records from YMO members and as well as on other collaborations within their circle. His relationship with YMO culminated with his marrying Takahashi’s ex-wife, Emiko, in 1995.

Naughty Boys was YMO’s final #1 charting album in Japan, with the often covered pop hit single “Kumi ni Mune Kyun” reaching #2 in Japan.

It marked a domestically-welcome focus on Japanese lyrics after their past international releases with original lyrics usually in English and written by Mosdell or Peter Barakan. The Human League recorded a cover of “Kumi ni Mune Kyun” with English lyrics by Philip Oakey:

Naughty Boys also contained the breezy lounge jazz Sakamoto song, “Ongaku,” written for his then three-year-old daughter.

A song reminiscent of 60’s French film soundtracks from Francis Lai, “Ongaku” was one of the few YMO songs besides “Behind the Mask” that Sakamoto would regularly include in his subsequent solo live electric band performances.

YMO’s Pioneering Music Production Achievements

With Billie Eilish winning Grammy Awards from records made in DIY bedroom studios and the plethora of plug-in virtual instruments available in today’s market, it is easy to forget how far and fast music technology has come since the 1970s. In hindsight, the innovations and workarounds created by Sakamoto, Takahashi, Hosono and programmer Hideki Matsutake to conquer the limitations of early analog and primitive digital music devices of the 1970s and 80s are even more impressive – on par with Alan Parsons’ extraction of a single bad note using a razor blade and tape on the analog multi-track master for Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon.

Matsutake, originally an assistant to composer and synthesizer pioneer Isao Tomita, was an essential member of YMO’s tech team. MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), the interface to connect instruments with sequencers and computers to make them play together in synchronization, did not yet exist. Matsutake’s groundbreaking solo electronic music work on records and TV made his relationship with YMO analogous in many ways to George Martin’s with the Beatles.

Matsutake first worked with Sakamoto on the latter’s solo recordings, using early Roland sequencers like the MC-8, which required keypad input of notes with quantized note values assigned. Matsutake worked with YMO to create a programmed groove by manually inputting data and varying note volume, timing and spacing values – a laborious and painstaking task.

Already promoting the Roland MC-8 sequencer in Japan and abroad, YMO would next become the trailblazer for one of the company’s most enduring products: The TR-808 drum machine. While it is now a hip-hop mainstay and the most recorded drum machine in history, the TR-808’s first recorded appearance was on YMO’s album BGM. Sakamoto only has two song credits on BGM and artistic clashes were starting to appear within the group. According to conflicting reports, Sakamoto either boycotted or was too ill to attend a number of recording sessions.

YMO was also one of the first groups to utilize digital sampling extensively. Matsutake introduced YMO to E-mu and Linn Drum sampling (with a customized sampler designed by Toshiba-EMI Music called the LMD-649) to incorporate triggers for sound effects and exotic instruments like Indonesian gamelans that were introduced on YMO’s Technodelic (1981), with the samples being reproducible live in concert.

Sakamoto’s primary YMO sounds were derived from popular analog synths of the day from Moog, ARP, Oberheim, Buchla and later, Sequential Circuits and Yamaha. Takahashi played a combination of Syndrums and a regular drum kit. Hosono alternated between a Fender bass and an ARP synth for bass lines. As seasoned musicians, they had the chops to play live even without the aid of sequencers and programmed parts, which often happened due to the digital units overheating, which would freeze up the tracks. The band would play on through as Matsutake would mute the sequencer instrument channels while rebooting.

While Ryuichi Sakamoto created much of his sounds on a monstrously large Moog III-C modular system akin to Keith Emerson’s, in addition to a Polymoog, ARP Odyssey and an Oberheim 8 voice, both Takahashi and Hosono played keys as well on their own demos. Sequential Circuits had released their Prophet-5 synth, which allowed for saving multiple presets in memory that could be recalled with the push of a button. This was a huge advantage over other synth manufacturers, which still required manual tweaking of knobs to change from one sound to another. The Prophet-5 appears throughout BGM on Hosono’s and Takahashi’s songs.

Inspirational: the Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 synthesizer.

Inspirational: the Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 synthesizer.With YMO at the forefront of electronic music technology in Japan, they were often called in for R&D consultation with musical instrument manufacturers. In what could easily be envisioned as a rivalry comparable to that of Sting’s devotion to the Synclavier vs. Stewart Copeland’s preference for the Fairlight CMI on the Police’s last records, YMO appeared to be in a similar contest within the new digital synthesizer realm.

Frequency Modulation, known as FM synthesis, was developed originally by John Chowning. It relies on variable algorithms for the oscillators and filters to alter sounds. As these numbers are numerical in value, they could be stored in memory in much larger capacity than with analog synthesizers from Oberheim, Moog, or Sequential Circuits. Yamaha licensed FM synthesis, and Ryuichi Sakamoto was among their highest-profile artists in Japan who would soon adopt the Yamaha DX-7 synthesizer. The bright, bell-like tones, percussion, and digital recreations of the Fender Rhodes electric piano among others were soon incorporated into Sakamoto’s equipment rig. Breaking a long-standing keyboardist tradition of carefully guarding one’s customized sound programs, Sakamoto became one of the first artists to market the exact sounds used on his recordings, with the Yamaha DX-7 Sakamoto KV-04 ROM series plug-in sound cartridges.

The sound that ruled the '80s: Yamaha's DX-7 synthesizer.

The sound that ruled the '80s: Yamaha's DX-7 synthesizer.The DX-7 would become one of the most popular synthesizers in history and almost defined the sound of 1980’s pop music on countless hit songs from Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, Toto, Kenny Loggins, and, of course, Sakamoto and YMO.

At the same time, Casio was developing its own digital synthesis platform, called Phase Distortion, or PD synthesis. Their main R&D artists were the renowned synth pioneer Isao Tomita, whose 1960’s classical recordings on the monophonic Moog synthesizer displayed the potential of synthesizers to emulate the timbres and parts of entire orchestras. Casio’s other resident R&D artist was Yukihiro Takahashi, who would use Casio’s CZ series of synths extensively on his subsequent YMO and early solo recordings.

While there are no reports of Sakamoto or Takahashi reaching the level of animosity of erasing each other’s parts to replace them with the synthesizers of their preference, such as in the anecdotal feuds between Sting and Copeland, conflicts of interest were emerging between band members.

Not unlike other supergroups whose members’ artistic directions diverge after initial success, YMO would take numerous hiatus breaks while Sakamoto, Hosono and Takahashi each pursued solo projects. They would regroup on occasion for tours throughout the 1990s and again in 2008 and 2012. YMO released its final studio album, Technodon, in 1993, billed as “Not YMO” due to Alfa Records in Japan retaining ownership of the YMO name. They also released two singles under the moniker ”Human Audio Sponge”/YMO, or HASYMO in 2007 and 2008.

YMO as a band notwithstanding, all three have continued to support each other’s solo recordings in the studio, just as they did in the genesis of the band’s formation.

Part Two will focus on Ryuichi Sakamoto’s solo work, his film scores, his collaborations into different types of ethnic music, and his activism.