Igor Levit – Tristan (Sony, 2022)

Emanuel Ax, Leonidas Kavakos, Yo-Yo Ma – Beethoven for Three, Symphonies Nos. 2 and 5 (Sony, 2022) 19439940142

Igor Levit, Tristan, album cover.

Even as they survey the widest solo repertoire of all, pianists are always stealing material written for others. They’re not happy with their two bravura Brahms concertos that work both as virtuoso showpieces and on a symphonic scale; they want to play the Brahms Violin Concerto in transcription and pretend they can hold a note as beautifully as any fiddler (pianist Dejan Lazic dared to record his version as “Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 3” (!) after Violin Concerto, Op. 77). Franz Liszt turned all of Beethoven’s symphonies into two- and four-hand piano transcriptions for the sheer joy of playing this music as recreation. As pianos became a piece of furniture throughout the 19th century, before radio and television, it signaled both educated status and a familial orientation.

Igor Levit, the gifted Russian-German pianist who delighted his audience with live Twitter house-concerts during the Covid pandemic back in March of 2020, devotes his latest recording to orchestral transcriptions, including the famous Prelude to Act I of Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, and the Adagio from Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 10 (arranged by Ronald Stevenson). These count as unusually ambitious selections even from this unusually ambitious pianist, centered around a new work, Hans Werner-Henze’s fantasy on Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, for orchestra and tape. (Henze’s passionately allusive piece includes an Ivesian interruption with Brahms’s First Symphony, accompanied by birds.) Levit bookends all this with glittering Franz Liszt displays (Liebestraum No. 3 in A-Flat Major, S. 541/3, and the 11th “Harmonies du soir” from Études d’exécution transcendante, S 139). Liszt, of course, ranks as the virtuoso’s best friend, and patron saint of the pianist as vampire.

The Tristan Prelude, arranged by the great Hungarian pianist and composer Zoltán Kocsis (1952 – 2016), accomplishes what most transcribers chase: to give the pianist more mountains to climb, and make you hear this most gargantuan music in miniature. Reducing such exuberant orchestration into 10 fingers on a piano, you listen to Wagner less as an orchestrator and colorist than as a mood-meister; the music’s effects rely less on timbre than voicing. Levit has superior control for this, and although pianos simply don’t sustain sounds as well as wind instruments, the spareness on this recording reveals an underlying fragility, and a new layer of self-consciousness.

In Levit’s version, the composer’s struggle itself gets laid bare, Wagner’s reach falling short of his grasp in the most expressive manner. The harmonies, which at the time sounded so radical that Wagner “broke tonality’s back” (in the music theorist’s maxim), have bloomed into Romanticism’s own dilemma, the very ineffability of putting emotions into sound. The playing is so spartan, so detailed, you almost wish Levit would release a draft without any pedaling, just to hear that much more closely how much coloration depends on the fog of sustain.

Pairing this with Mahler’s Tenth Symphony doubles down on the pianist’s commitment to transcription as a genre. In his youth, of course, Mahler was a stone Wagnerite, and turned into one of this composer’s greatest conductors. He internalized that music of his youth beyond anything he could articulate, and by his Tenth Symphony, he sketched an unfinished world of post-mortal anguish.

Leave this CD on, and Tristan flows straight into the Mahler, delivering both a new frame and an odd sense of historical continuation. Mahler’s groping melody lurches from starting point to starting point until it lands on a ghostly dance. The intense frailty of life here assumes an intimate scale. Orchestrators and composers disdain piano reductions for ignoring the richer colors a ripened viola section brings this material. But imagine what Mahler himself heard, playing this music alone at his piano, before he started to orchestrating.

As the most famous conductor-composer of his era, forced to convert to Catholicism in order to take over the Vienna State Opera in 1897, Mahler’s Jewish Bohemian roots preoccupied his imagination. Like Shostakovich, Mahler turned his public dilemma into a subject: how to appease a state apparatus that could never appreciate the subtleties of his music, and therefore forced a belief system on its composer who was busy discovering and exploring a radical crisis of belief through his scores?

Listen to your favorite recording of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, and you hear a searing finality, a farewell to the Viennese symphonic tradition, and perhaps the world itself, that sounds so overwhelming that mere applause feels like the meekest possible response. Even on the early recordings by Mahler’s apprentice Bruno Walter, you sense musicians struggling with Mahler’s profundities: a summary of both a life in music and a life spent answering Wagner in non-operatic, non-programmatic music (as a finale), that expresses Europe’s better idea of itself. His Ninth Symphony lurches between elegant and tumultuous, fiercely proud and climactically neurotic, sitting on “top” of world history even as that (Western, white-privileged, aristocratic) history, and then colonialism itself, began to unravel. Leonard Bernstein was fond of saying Mahler foresaw the horrors of the 20th century, that he was lucky to sense Germany’s fate as prophecy instead of reality.

Mahler himself felt so anxious about composing a Ninth Symphony in the shadow of Beethoven that he didn’t even call it his Ninth: he chose a programmatic title, Das Lied von der Erde, a set of songs, before penning the “symphony” that we now call his “Ninth.” So his Tenth symphony posed a unique question: what to say after you say farewell? How to start over once you’ve tried to summarize an entire Viennese tradition?

Mahler starts by addressing listeners from some great beyond, a melody finding its voice, slipping in and out of itself as if taunting gravity. After about twenty minutes in, it builds to a climactic crisis, with shrieking trills and huge, bombastic chords, the kind that don’t even seek resolution. After exasperation, emptiness, and abandonment, things return to the main theme only as false consolation. This thinning solace can’t quite achieve sincerity; it may not provide much comfort, but it’s all Mahler has. Nothingness cannot find peace, it’s probably not even looking for it. You sense the composer’s breath struggling, wondering how and where the next subject might come, and if it doesn’t, how to express that inevitability.

It all thins out to single notes, proclaiming an outline of melody in slow motion, harking back to the full drama from the opening strains in a naked, apologetic farewell. Here, the piano sounds fall away so quickly you can’t help but hear an orchestra chiming in through your imagination; the sounds call for something more than hammer on strings. And that final chord seems gratuitous, self-mocking, a door shut in defeat.

When a piano’s hammer hits its strings, the sound begins to decay immediately; the effects Wagner and Mahler sought from strings and winds veer in the opposite direction, which makes these piano renditions intriguing, almost as if you’re hearing a negative image of the music, a way of seeing the notes from behind, or hearing through a peephole of a parallel universe.

The other shift occurs as Levit personalizes a music meant for an ensemble. What a group of musicians does with these scores gets shaped and massaged by a conductor, but the collective enterprise soars above any single individual. As Levit plays these notes, you hear one person’s will, as if a collective spirit could get channeled through one man’s hands. (Imagine each individual orchestral player pulling a string to control one pianist’s finger.)

Mahler doesn’t make more sense heard this way, but the music falls into a huge relief; its ambitions suddenly manifest on a different scale, its ineffability glimpsed if only for a moment as if it could find containment.

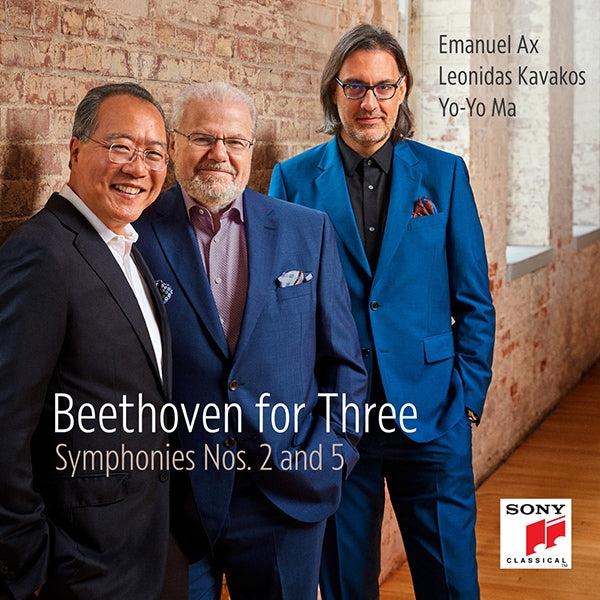

Emanual Ax, Leonidas Kavakos, and Yo-Yo Ma, Beethoven for Three, album cover.

Another example of how arrangements warp familiar symphonic repertoire gets a scrimmage from a superstar trio: Emanual Ax, Leonidas Kavakos, and Yo-Yo Ma. In 2017, this troupe turned in a fine set of the Brahms Piano Trios, with thick vibrato and sweeping dramatic gestures that gave this chamber music symphonic proportions. Of course, it had polish to spare and at some points sounded effortless, which was part of the point: three virtuosos breezing their way through Olympian hurdles. But overall, it seized such bravura and daring it counted as irresistible.

This new recording shrinks two Beethoven symphonies down to three parts, crystallizing larger flourishes into compact gestures. Groups like the Beaux Arts Trio or the Emerson String Quartet spend decades working on their blend, so when celebrity soloists take on this repertoire there’s some arrogance involved: “We can flat-out play the stuff you devote your careers to on command,” they seem to say, “and look, we sell more!”

But some of these superstar ensembles can teach you about the music’s challenges even when they don’t secure the same ensemble peaks. It’s like watching Shakespeare with a celebrity starring as Hamlet: how does the material itself play against fame?

Here, conductors and composers carry more weight: nobody would choose a piano trio rendition of Beethoven’s Fifth over, say, that new cycle from Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. But in this era, why choose? Play them back-to-back and I dare you not to find fascinating choices; odd silences erupt, tempos that seemed firm suddenly wiggle free, and spontaneity takes over. You can’t help but admire the paces Beethoven puts any player through, in small groups or larger, and how well the music speaks through any context.

Violinist Leonidas Kavakos seems to get more from Ax and Ma than so much of their earlier sonata recordings, a spur of sound that makes even this small form gallop. In the Second Symphony, this most underrated Beethoven explores all characteristics of great Beethoven before his greatness acquired quotation marks. The Fifth bears many surprises; when listening to it on three instruments a different layer of tension takes shape: not merely in the opening gesture, played here like pulling a ripcord, and then chasing all the notes downward, with a roomy, elastic feel, as though unwinding at its own steam. There’s a lot less violin and cello vibrato here too to better frame Beethoven’s elemental candor.

The Fifth’s slow movement (“Andante con moto”) translates anywhere; you could play it on an accordion and accordion-haters would love it – even on social media. These two string players bite down into their parts like orchestral players cut loose from rote ensemble. The quiet sections have more intrigue, the louder parts don’t have the same heft, but in the relative context, they carry a similar weight. Overshadowed by its more famous opening Allegro, this movement counts as more underrated than even the Second Symphony. These players also have another Beethoven disc on the way: Symphony No. 6, the “Pastoral.”

Of course, a pianist’s ears have innate bias, these translations don’t work for everybody, and they can’t possibly replace their full orchestrations. But sometimes familiar music casts different shadows when heard from a completely different orientation, like using a favorite painting as a screensaver. You don’t mistake it for the real thing, but it can help you appreciate why the real thing never fit onto a small screen in the first place.

Header image: Igor Levit, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Feast of Music.