The Four Seasons is one of the most-recorded works in all of classical music. A quick search of Spotify yielded over 500 versions, and the results hadn’t even finished loading. With that level of saturation, it’s not surprising that a number of recent attempts have focused on rethinking this timeless work.

Antonio Vivaldi’s most famous composition, first published in 1725, is a set of four violin concertos, considered “programmatic” music in that each is paired with a sonnet about one of the four seasons of the year. The composer may have written the sonnets himself, although that is still under debate. He also added dramatic cues on individual parts, such as “Dog barking” during a viola passage in the “Spring” concerto. This kind of extra-musical reference was avant-garde at the time, and the reception to the work varied widely, from adulation to mockery.

The earliest known arrangement of the Seasons for alternate instrumentation dates all the way back to 1739, when French composer Nicholas Chédeville reconceived the solo lines to feature his own specialty, the musette (small, delicate-sounding bagpipes with two chanters and a bellows under the elbow). He indicated on the score that one could substitute a hurdy-gurdy if one preferred. Since then, Vivaldi’s masterwork has never stopped inspiring new variations.

As a reference point, let’s start with a recent performance using Vivaldi’s original score, a Warner Music release by the Janaček Chamber Orchestra and violin soloist Bohuslav Matoušek under the direction of Zdenek Dejmek. The sheen of new spring shoots and the warbling of birds building their nests are painted vividly in their interpretation of “Spring.” This is not a particularly historically informed performance – Matoušek uses standard post-18th-century bowing pressure, vibrato, and metrical elasticity, as does the orchestra – but the playing is clear, precise, and energetic. This is one of hundreds of perfectly pleasant and adequate recordings of The Four Seasons.

There’s a lot more originality in the version for cello recorded by Luka Šulić and the Archi dell’Accademia di Santa Cecilia. Maybe a little too much originality, especially when it comes to phrasing. Conductor Luigi Piovano seems to work tirelessly to make every phrase meaningful and new, when the change in pitch and timbre of the solo instrument is enough on its own to make us listen differently.

Šulić wrote the compelling re-orchestration himself, and the melodramatic interpretation of rhythms and dynamics, barely related to the expectations of Baroque music, may stem from his main gig as half of the pop-music duo 2Cellos. It’s fun, but is it Vivaldi? Of course it is, just not in a way the original composer ever heard it.

For a completely different take on Vivaldi, there is the experiment by German-born British composer Max Richter, called The Four Seasons Recomposed. Not so much a re-orchestration as a change at the cellular level, this work was premiered by violinist Daniel Hope in 2012. A newer interpretation recently came out on Rubicon Classics by violinist Fenella Humphreys. Ben Palmer conducts the Covent Garden Sinfonia.

What Richter has done is imagine Vivaldi’s score as a cache of old material to use in new ways, preserving the original programmatic intent but imbuing it with a 21st-century sensibility informed primarily by minimalism. The harmonic motion is different, less goal-oriented, but the dramatic arc still works.

Humphreys’ playing has a pure sweetness to it that perfectly evokes the colors and scents of the great outdoors. No matter how much Richter reuses the Vivaldian phrases, the listener is not wearied by repetitiveness; Humphreys takes each phrase as a unique statement on its own, without regard to how similar the previous or next phrase is.

Richter is by no means the first composer to disassemble and rebuild the Seasons. Argentine composer Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) turned the whole set of concertos into an exquisitely angular four-movement Latin dance. It’s a gorgeous piece, newly composed with tango-like syncopation and flair, yet generously studded with big, juicy nuggets of Vivaldi.

A new live recording by the Orchestra of St. John’s, Oxford, on the orchestra’s own label, is conducted by John Lubbock and features Jan Peter Schmolck on violin. The opening begins at the 41:00 mark. But if you have the time, I recommend their sparkling reading of Vivaldi’s original that leads up to the newer piece.

You’d think that Piazzolla’s and Richter’s deconstructions of the work would be the least Baroque thing to be done with it, but that’s not the case. The prize for most intense anachronism goes to pianist/composer Mistheria, whose self-released Four Seasons for solo piano blends the rhythmic malleability and relentless sustain-pedaling of late Romanticism with the emotional flotation of New Age music. Here is the final movement of “Winter.” There is barely a trace of Vivaldi in this, even though all his notes are still present.

When Piazzolla wrote the version mentioned above, he intended the solo instrument to be accordion or bandoneon, which is what he played. A more recent, and more straightforward, re-orchestration for accordion and strings was recently prepared and recorded by Lithuanian accordionist Martynas Levickis, accompanied by the Mikroorkéstra Chamber Ensemble.

The high-frequency reediness of the solo instrument takes some getting used to, as does the folkish articulation that sometimes stops to scoop up extra ornamentation. But it’s worth the effort to adjust, since Levickis is astonishingly virtuosic at his instrument. That is not an excuse, however, for the final movement of “Spring” to be quite so fast.

It’s harder to know what to make of Karl Aage Rasmussen’s Four Seasons After Vivaldi, released on the Dacapo label by Concerto Copenhagen under the courageous leadership of Magnus Fryklund. Violin soloist Fredrik From has a bracing wildness in his brilliant and accurate playing.

But none of that explains the underlying purpose of Rasmussen’s exercise, and that’s just what it feels like – an exercise. The living composer has left his Baroque forerunner’s instrumentation and notes, but interrupts and distends the rhythm and meter violently. Remember the abrupt digital hiccup of a CD skipping? Rasmussen causes that discomfort on purpose, over and over. This orchestra is so good, though, that you’ll want to seek out their recordings of actual Baroque music. Their Corelli concerti grossi are glorious.

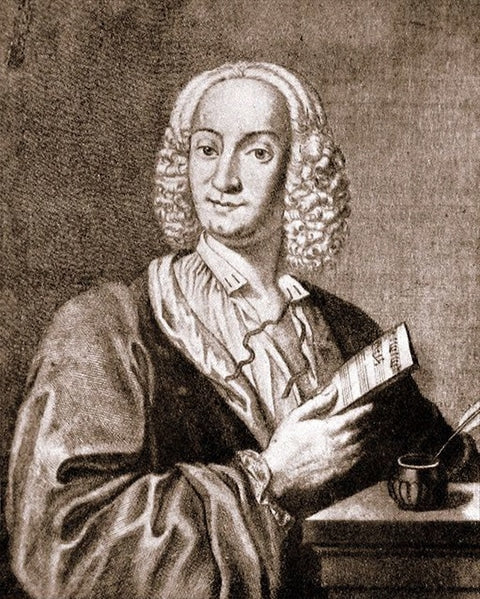

Header image: Antonio Vivaldi, public domain.