In the previous episode (Issue 170), we looked at the Hara disk recording lathes, manufactured in Japan in the 1970s.

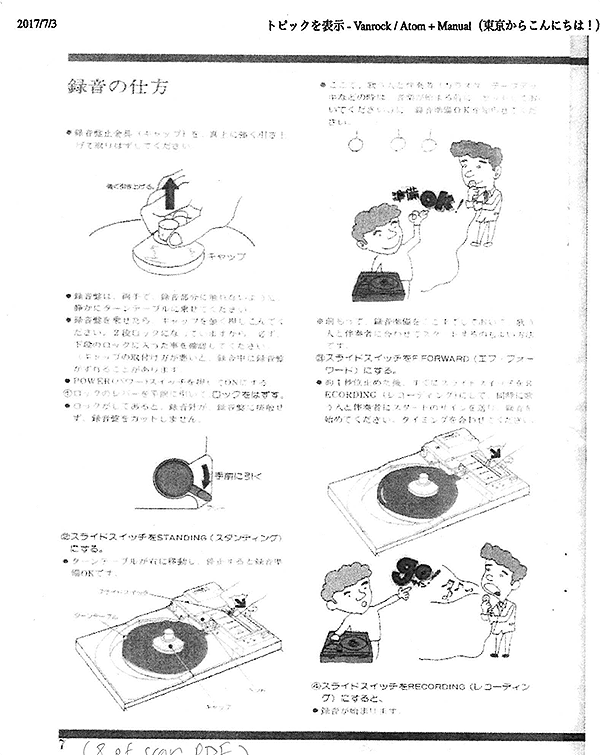

The Vanrock E-101 and the Atom A-101 came a bit later, in the early 1980s. Although similar in terms of portability, the Vanrock and Atom machines were very different to the Hara products. The Vanrock and Atom are essentially the same machine, manufactured by the same factory and having identical manuals, but branded differently, for reasons beyond my comprehension. The Vanrock/Atom has a belt-driven platter that could record on 7-inch blanks. The head was stationary, and the platter would move under the head, in a manner similar to the disk recording lathes of the early acoustical recording era (although in more recent times, the concept has been revived, first by Phonocut and later by Thorsten Scheffner of Organic Music in Germany, who made a few custom lathes based on this principle).

The only similarity to the Hara machines was that the Vanrock/Atom was also built into a briefcase and had built-in electronics, including a microphone preamplifier. Designed with a notably modern approach to aesthetics, perhaps more so than any other disk recording lathe ever made, it resembled some kind of space-technology gadget right out of a science fiction movie. As with the Hara lathes, its sound quality left a lot to be desired, but it did contain everything you would need to cut a record in a fairly lightweight, portable package! The built-in audio electronics even included a simple compressor, to keep the dynamics under control even when the level was incorrectly set, or to accommodate difficult recordings with no need for dedicated studio equipment. In a sense, these machines were to a professional disk mastering lathe what a Swiss Army knife is to a fully-equipped machine shop.

Atom A-101 disk recorder. Courtesy of Dylan Beattie, Sussex, England, https://furrowedsound.co.uk.

Another view of the Atom A-101. Courtesy of Dylan Beattie.

Fast forward to the late 1990s and early aughts: the vinyl record is no longer king, sales were plummeting, the major record labels didn’t want anything to do with it, record stores didn’t want to stock records, pressing plants were either going bankrupt or sending all their equipment to the scrapyard to make space for optical disk manufacturing equipment, and consumers around the world had started throwing entire record collections in the trash, convinced by clever marketing that they were now worthless, having been rendered obsolete by the promise of “perfect sound forever” in the form of digital media.

Just when pretty much the entire rest of the world was getting rid of everything related to vinyl records, a company in Japan decided to introduce yet another consumer-oriented disk recording lathe! This time it was a fairly large, export-oriented company, with a strong foothold in the DJ market, internationally. It was an ambitious move and the result was even capable of cutting stereophonic records! We are talking about Vestax, which introduced the VRX-2000 lathe in 2001! It retailed for around $10,000 in US dollars, and was not exactly successful. It was aimed at the consumer market, or perhaps the “prosumer” market, and lacked many of the essential features of a professional disk mastering system. It was the only stereophonic recording lathe at the time that was not aimed at professional mastering facilities, and at the same time, the only lathe in active production, with an international network of dealers. However, the price was perhaps higher than what the consumer market would accept, and came at the lowest point in history for vinyl record sales and appreciation. Although it did look quite impressive, compared to pretty much all other attempts at consumer disk recording equipment, it was still a beefed-up version of a DJ turntable with a cutting attachment on top and built-in audio electronics of questionable performance. It had a fixed-pitch system, giving a recording time of approximately 14 minutes per side of a 12-inch record.

Vestax VRX-2000 record cutting machine.

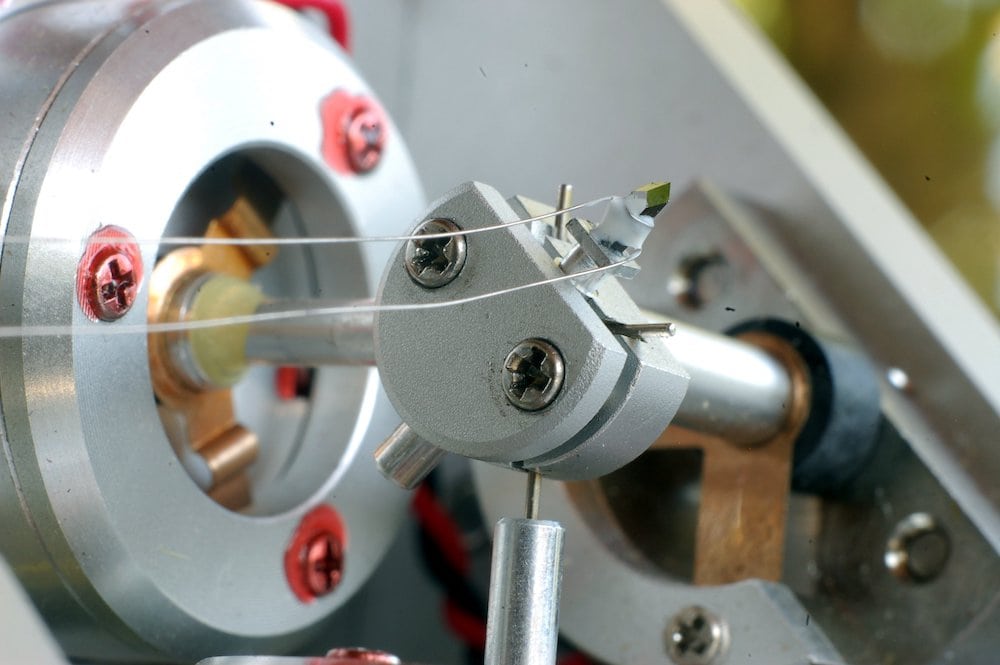

Macrophotography of a Vestax VRX-2000 cutter head, repaired and modified by the author to accept a Neumann-type stylus. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

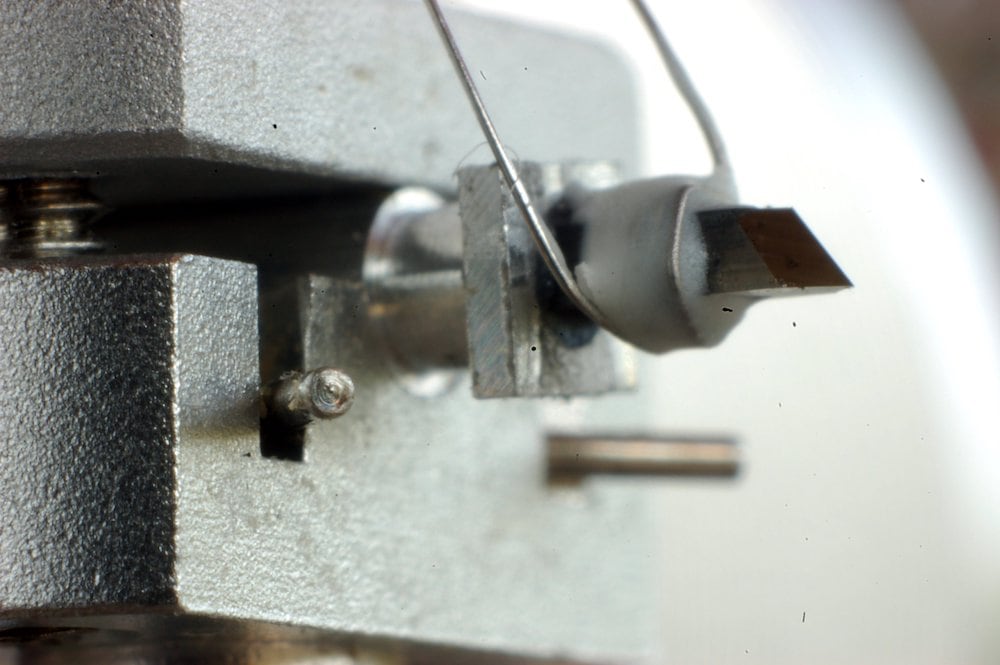

Close-up of the Neumann-type stylus, seated on a modified Vestax VRX-2000 cutter head. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

The stereophonic cutter head borrowed heavily in design from the established professional cutter heads, but with all the difficult-to-implement features trimmed out. It did not have motional feedback, relying entirely on mechanical damping instead. The idea was actually quite good, but rather poorly executed. The materials and configuration chosen in its design did not age well, and users of these machines complained of poor reliability. Despite this, there are still a few in operation nowadays, but they have been repaired and often modified, to be kept running. Very few of these were ever made, and Vestax went bankrupt in 2014.

The Vestax VRX-299 cutter head and J.I. Agnew’s macrophotography setup, with a Nikon bellows attachment, as a symbolic gesture in honor of Japanese engineering. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

While a few Japanese companies have been quite industrious in (repeatedly) trying to establish the notion of a consumer-grade disk recording lathe over the years (starting in the 1960’s, but information is difficult to find), there was never a professional disk mastering lathe made in Japan. However, Japan does currently hold the global monopoly in the manufacture of lacquer master disks, disk-mastering sapphire cutting styli, and perhaps also the mass-manufacture of diamond playback styli for phono cartridge manufacturers.

Perhaps if things change yet again and the vinyl record resurgence comes to an end, some company in Japan will decide that the timing is wrong enough to introduce a professional disk mastering system, or even yet another consumer-oriented disk recording lathe. For the time being, their focus is on the consumables side of the market.

Regardless of what lathe is being used and where it was manufactured, all currently-manufactured records mastered on lacquer are cut on Japanese lacquer disks with Japanese styli. DMM (direct metal mastering) remains an exception, with both the blanks and the styli for the process still being manufactured in Germany. As for the consumer market for disk recording equipment, it is presently bigger than ever, with a supply of vintage and usually fairly primitive machines serving it, along with an increasingly growing scene of people attempting (with varying degrees of success) to build their own disk recording lathes from scratch.

A page from the Japanese Vestax VRX-2000 manual.

Header image: Atom A-101 disk recorder being used in live performance. Courtesy of Dylan Beattie.

0 comments