[Tom Fine is an archival/recording/mastering engineer, and if if his name sounds familiar, it’s likely because he’s the son of Robert Fine and Wilma Cozart Fine. One of the rare husband-wife teams in music production and recording, Robert Fine ran the Fine Sound and Fine Recording studios, and Wilma Cozart Fine was the VP of Mercury Records, known for producing the legendary Living Presence series. Tom spoke with John Seetoo for Copper, and shared details of growing up in an intensely-artistic environment, and of his own career. —Ed.]

John Seetoo: Robert Fine is considered one of the pioneers in high quality film sound and recognized early on that 35mm mag tape was a medium that could yield very high fidelity recordings. One bio referenced his earlier work as a teen in the film industry, his stint in the US Marine Corps working with communications and his time at Majestic Records. Do you think that these experiences had any bearing on his innovative ideas and the decision to purchase Everest Studios? Do you recall what the industry reaction to this approach was when Fine Recording started featuring it more prominently in its recorded output?

Tom Fine: I was born in 1966, and by the time I became aware of music and recording, my father’s studio was in its final years.

Regarding 35mm as a master recording medium, it was used by Everest and then Mercury, Command, Cameo-Parkway, Capitol and others. It was marketed as a “super hifi” way to make records, and there were certain technical parameters where it performed better than the magnetic tape and tape recorders of the day (such as a lower noise floor, less print-through, less audible wow and flutter). Because film cost a lot of money vs. tape, and because tape recorders and tape formulations got better, among other factors, the 35mm fad was short-lived.

The 35mm recording trend was short-lived, but fun while it lasted.

Regarding my father’s background, his first job, in high school was at Miller Studios in NYC. Mr. Miller had invented the Philips-Miller sound-film recorder (do a Google search for details, it was quite innovative in its time because it allowed for instant playback as well as simple scissors and sticky-tape editing, with acceptable audio fidelity). He enlisted in the Marines after Pearl Harbor and was quickly promoted to Tech Sgt., teaching RADAR at Camp Lejeune. He eventually deployed to the Pacific, stationed in the Marshall Islands. After the war, he was hired as the engineer at Majestic Records’ newly-constructed studio in Manhattan. There he met and began working with John Hammond, who was producing Mildred Bailey for Majestic. Hammond went on to work for Mercury Records, and that’s how my father got connected with the then-new independent label.

JS: Wilma Cozart Fine was the VP of Mercury Records’ classical division. Did she exercise much executive decision making over the choice of artists and material to be recorded for the Living Presence series? What do you recall about her influence on Fine Recording’s direction, as her re-mastering work on the Living Presence series in the 1990s indicates previously under publicized technical expertise?

TF: My mother took charge of Mercury’s classical division when John Hammond left the company, around 1951. Mercury had made a few original recordings, mainly chamber music, but had mostly reissued European recordings licensed from the Czechoslovakian Culture Ministry by Hammond. Among those recordings were a number of German Telefunken recordings made during the war years. The Czechs had seized the disk masters as war spoils. Well, Capitol Records, working through the War Reparations Board, made a license deal with Telefunken for the same material, even though Telefunken owned only second-generation copy discs. Capitol sued Mercury in the U.S. and won the exclusive right to sell those recordings here. So Mercury’s classical catalog was suddenly reduced to a small collection of recordings. At the same time, many U.S. orchestras were without recording contracts due to a number of factors. My mother urged Mercury’s founder and president, Irving Green, to sign the Chicago Symphony and its new conductor, Rafael Kubelik, to a contract. Mercury succeeded and thus the stage was set for the company to make its own orchestral recordings. By that time, my father was working for Reeves Studios but was about to leave and start his own company, Fine Sound. At Reeves, he had discovered and become one of the first U.S. users of the Neumann U-47 microphone (which at that time was exported by Telefunken). Also at Reeves, he had developed a method to record an entire ensemble with a single microphone, which produced a very realistic balance and sound-picture. He took his U-47 to Chicago and made the first Mercury Living Presence recordings in April 1951. The NY Times review of that recording of “Pictures at an Exhibition” described the listener as “in the living presence of the orchestra.” My mother knew a good marketing slogan when she saw one, and got permission to use “Living Presence” as the classical brand.

As for my mother having influence over my father’s studios, she did not, because my father was never an employee of Mercury. Rather, he was always an independent contractor. That said, my father very much respected my mother’s opinions about what sounded good and what didn’t sound good, and was good at figuring out, technically, what she was hearing or what was missing in the sound. They worked well together because he had well-developed ideas about how to make recordings and she had well-developed ideas about how things should sound and they were able to find a way to use his technical knowledge to achieve her aesthetic with the Mercury Living Presence recordings. Another important thing about both of them, they were always open to new ideas and tweaking their technique to get better results. I think they always felt they could get closer to the “living presence”, and never stopped innovating.

(Regarding} the last part of your question: My mother did the 3-2 mix, in the analog domain, for all of the Mercury LPs and CDs she produced. Bob Eberenz built her a custom 3-2 mixer out of Westrex components. So I would say she did do some “engineering”, but she didn’t consider herself an engineer. Luckily Fine Recording and later Polygram Studios in Edison, NJ didn’t have crazy union rules barring a producer from mixing or otherwise touching equipment (such rules existed at Columbia and RCA studios, among others).

JS: What was it like to grow up around all those musicians and all that creative activity? Do you have any favorite anecdotes or memories of that era?

TF: By the time I was growing up, my mother was long retired from the record business. However, she was still good friends with the pianist Byron Janis, the wind-band pioneer Frederick Fennell, her former Music Director Harold Lawrence and of course my father’s former right-hand man, Bob Eberenz. So I do remember visits from these people. Bob Eberenz ended up being extremely helpful to my mother when she undertook the CD remastering project, and he became my dear friend and mentor.

My father passed when I was 16 and my mother kept a roof over our heads and kept our family together by starting a career in real estate. She ended up being very good at it, and those days of selling houses paid for my and my younger brother’s college education. I am eternally grateful for her grit and positive attitude in those years. She was successful at real estate, but it was not an avocation for her. So when Philips/Polygram, then the owner of Mercury Living Presence, decided to reissue the catalog on CD and approached her about overseeing the remastering, this was a very good turn of events for her. She was able to have a second career in a business she loved, and of course she had a lot of success with the CD reissues.

JS: Robert Fine is credited with helping to develop Perspecta Sound – an early multi channel film sound platform that he collaborated with Loew’s Theaters for wide screen projection. Can you tell us about Perspecta Sound and its genesis? What do you think your father would have thought of today’s film sound state of the art innovations and quality?

TF: My father invented PerspectaSound, which was a compatible method to have a 3-channel soundtrack on a standard mono optical film print. Theaters without PerspectaSound equipment would play the film with mono sound. Theaters with Perspecta equipment would have the sound spread out over 3 channels behind the screen. You can use Google to find out details of PerspectaSound, particularly at the Widescreen Museum website.

Throughout his years as a studio owner, my father did a lot of sound-for-picture work. One of his areas of expertise was many-channel sound mixes for very-wide or multi-screen films produced for events like the NY World’s Fair, Expo67 and Hemisfair in San Antonio. So he was definitely very clear on the various elements of film-sound and film-sound production and mixing. I assume he’d get a kick out of the fact that I can put a DVD in the player and have convincing 5.1 sound right in my den, and in fact I bet he’d have some sort of home-theater setup. The bigger question is, would he want to watch any of the movies made these days?

JS: As they were audio innovation contemporaries in somewhat similar fields with a bit of crossover, do you have any recollections of Robert Fine ever discussing his opinions about and/or work with Robert Moog, Walter Sear, or contemporaries like Les Paul?

TF: Walter Sear was a musician in NYC in the 60s. He played tuba and also developed some expertise at the Theremin electronic instrument, which he played on some Command Records sessions at Fine Recording. Later in the 60s, Walter got in business with Robert Moog, at first selling Theremins that Moog designed and built, and later as the eastern U.S. representative for Moog synthesizers. My father made a deal with Walter; he set Walter up with his own production studio at Fine Recording in exchange for Walter producing Moog sounds and effects exclusively for Fine Recording clients. As you can imagine, this locked in quite a bit of commercial/industrial sound business, plus some movie-soundtrack work and a series of Moog records for Command and other labels. When Fine Recording closed up shop in the early 70s, Walter bought some of the equipment and set up his own studio in Manhattan. He went on to have a long run as a studio owner.

My father never worked with Les Paul. My younger brother does play a Les Paul guitar and got Les to sign it one night at the Iridium Club in NYC.

[The rest of John Seetoo’s in-depth interview with Tom Fine will run in Copper #50 and #51. In part 2, Tom discusses some of Fine Sound/Recording’s clients and the musicians involved in all those recordings, as well as the birth of mobile recording. Thanks to John and Tom for a really fascinating interview! —Ed.]

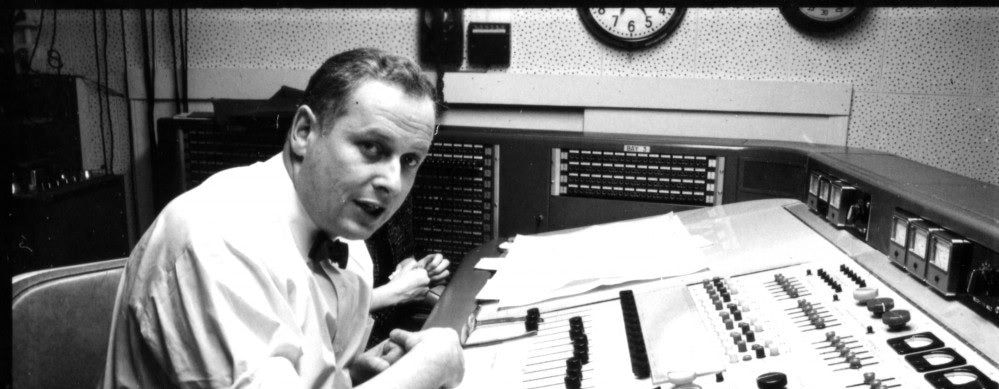

[Header photo is of C. Robert Fine at the Westrex recording console at Fine Recording Bayside, Queens, which was originally the Everest Records studio. All photos courtesy of Tom Fine.]