When I was in fourth grade, I enrolled in Manhattan Music School. Not to be confused with The Manhattan School of Music, a private conservatory near Columbia University. The school I attended was on 84th Street and Madison Avenue above a diner and a ladies’ clothing consignment shop. Once a week, I would climb the long flight of worn linoleum stairs to a dusty wooden floor arrangement of small studios with scratched upright pianos and gray fluorescent lighting.

Mr. Adams, my first teacher, was a pleasant young man who made my beginner’s pieces sound musical. He even showed me how to strum an acoustic guitar and blow a saxophone that tasted of tarnish and spit. After a year, Mr. Adams left, and an older lady took over my education. With her fixed expression and Slavic accent, she taught piano according to the old method: a solid foundation to be established by rote, practice, and hand strengthening exercises.

My practice instrument was a piano owned by an old-time Broadway star, Dorothy Lindsay, also known by her stage name, Dorothy Stickney. Her husband was Howard Lindsay, half of Lindsay and Crouse, who, along with Rodgers and Hammerstein, was the team that created The Sound of Music on Broadway in 1959. Howard Lindsay and Russell Crouse were both dead by 1977, so the piano sat idle unless one of Mrs. Lindsay’s theatre cronies played it during cocktail parties. Otherwise, I was the only other person to make its lush tones come to life.

My mother spent her days as Mrs. Lindsay’s chef, and I hung out in the kitchen most afternoons and weekends. I loved being in that townhouse off Fifth Avenue and 94th street. It was full of dark corners, unused spaces, and a creepy cold basement with a coal room used to store wood for the fireplaces.

On weekends, I would volunteer to take Dorothy her breakfast. When she awoke, Mrs. Lindsay rang down to the kitchen on an ancient intercom, letting the staff know she was ready to dine. As the white buttered toast, poached eggs, bacon, marmalade, and pot of tea were being plated, Mrs. Lindsay performed her toilette before she could be seen, even by a 10-year-old. I placed the tray and morning papers onto a cart and rode the two-person elevator from the ground floor to her room on the third floor. At the opposite end of a long hall was Mr. Lindsay’s bedroom suite, which had been left intact and used as a guestroom. The floor above was for the live-in help. The second floor consisted of an office and my music room; dining and living rooms were on the first, and an antiqued parlor was on the ground floor in front of the kitchen.

Mrs. Lindsay, a frail 80-year-old in a 1920s flapper wig and bright red lipstick, was perfumed and propped up on a giant bed, dressed in a frilly robe and flanked by two cats: one a regal Siamese named Madam, and a creamsicle Angora, Butch, who was very sweet but ignored. As soon as Butch realized he could get attention from me, he began following me wherever I went.

Mrs. Lindsay had no children, and I had no grandparents in America, so our moments together were familial. I sat at the foot of her bed, and we talked about school, the musical pieces I was learning, and what my performance plans were after fifth grade. Mrs. Lindsay could hear me from her room, and she encouraged me to practice. Piano was the basis for everything – the springboard for other instruments, singing, and composition. There’s not a stage or rehearsal space without a piano. But I didn’t want to be like her friend Oscar Hammerstein or Vladimir Horowitz, who lived down the street, or even Elton John. I wanted to play guitar like Brian May, but my stepfather considered electric guitars and drums vulgar, and the people who played them “low class.”

Several days after school, I brought my school-supplied vinyl attaché packed with my latest scribbling in my composition and workbooks, along with various pieces of sheet music to practice on Lindsay’s black grand Steinway. The instrument was polished and well maintained. It had no scratches, the hammers were new, and its strings all attached and tuned. However, Butch and I preferred to explore the music room filled with souvenirs, portraits, black and white photos, show posters, programs, and awards. There were cabinets, drawers, and closets stuffed with records, sheet music, and wind-up music boxes. I guess all the artifacts appealed to the historian in me, while an aspiring showbiz kid would have come away with a greater appreciation for the golden age of Broadway or at least Mrs. Lindsay’s most well-known play, Life with Father, which launched at the old Empire Theatre in 1939 and ran for 400 weeks.

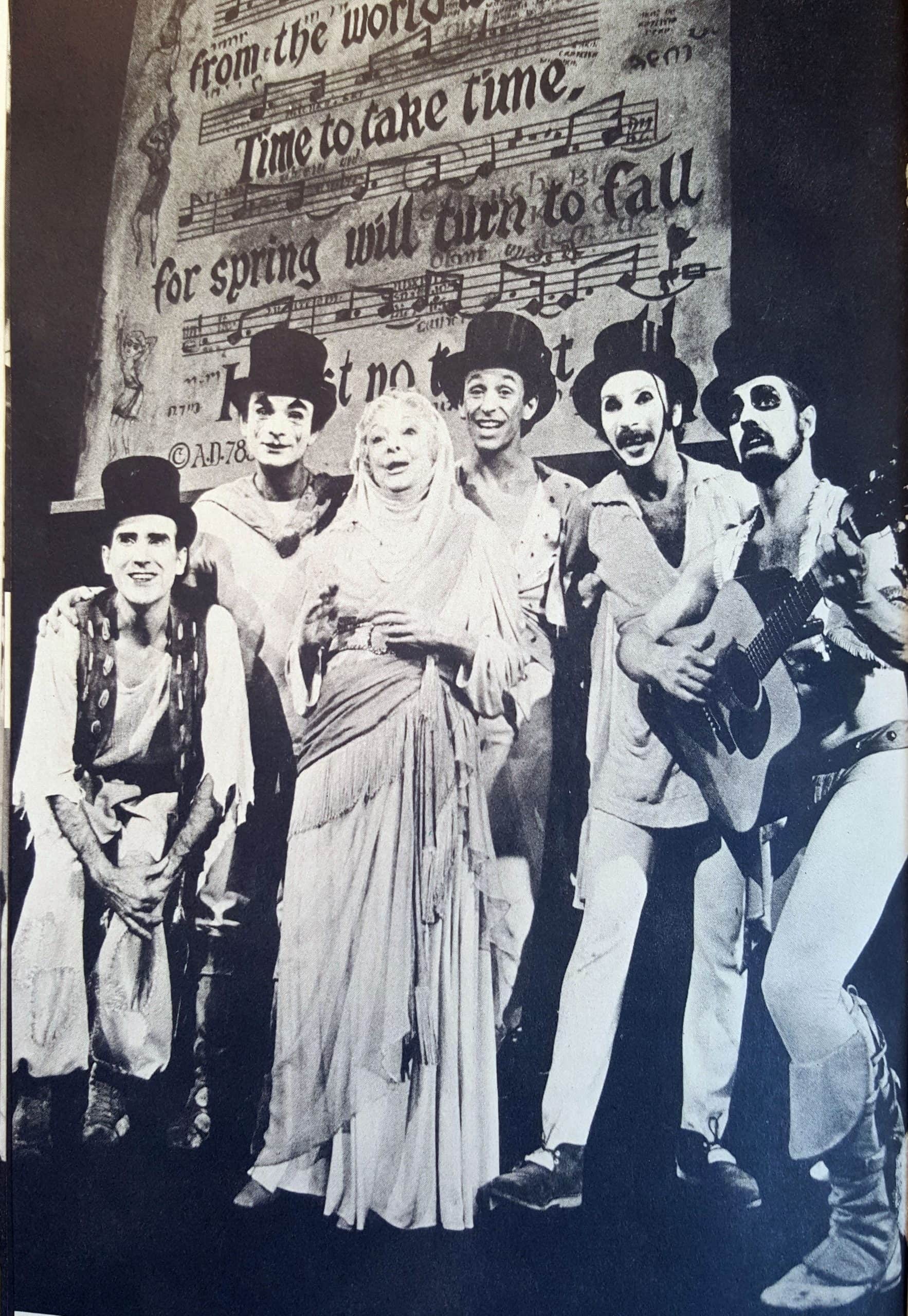

I was too obsessed with the guys in Creem and Hit Parader magazines to understand that Mrs. Lindsay was a rock star in her own right who had done vaudeville, talkies, television, Hollywood movies, and theatre. My mother heard her sing in Bob Fosse’s Pippin on Broadway just a few years earlier when Mrs. Lindsay was still working at 76 years of age. I do feel like I cheated my parents out of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. If I had only been born with a few of Mickey Rooney’s song and dance genes, maybe Mrs. Lindsay could have catapulted me to stardom. Instead, all I came away with was a dowagers’ love for orange marmalade, Earl Grey tea, and cats.

Playbills from personal collection: Pippin Playbill, Imperial Theatre, October 1973; Life with Father Playbill, Empire Theatre, April 1944.

Playbills from personal collection: Pippin Playbill, Imperial Theatre, October 1973; Life with Father Playbill, Empire Theatre, April 1944. Dorothy as Berthe in Pippin. Her final theater role. From Stickney, Dorothy, Openings and Closings: Memoir of a Lady of the Theatre. Personal collection.

Dorothy as Berthe in Pippin. Her final theater role. From Stickney, Dorothy, Openings and Closings: Memoir of a Lady of the Theatre. Personal collection.After fifth grade, my family relocated 40 miles north of New York City to Bedford, NY. I thought moving would cancel the lessons, but my stepfather loved the piano and was determined that I should master it. Perhaps he envisioned summoning me to the salon to entertain our cultured friends and family with a few licks of Minuet in G minor (which seemed like the only piece I ever played). Thankfully, we never owned a piano, never had space for a piano, and never had money for one. By some turn of misfortune, my stepfather found a new place for me to practice: at his boss’s house. Lessons resumed.

This piano sat in a gentleman’s library with built-in bookshelves that seemed 50 feet high, leather chairs, a desk the size of my bed, and a billiard table. From the big picture windows, I looked at the swimming pool and tennis court. Though I’m sure the piano was first-rate, I remember absolutely nothing about it. The people who lived there had two kids, the darling teenage Katherine with a tan, braces, chestnut Farah Fawcett curls, and what I imagined to be strawberry-flavored lip gloss. Then there was her brother, a tow-headed boy younger than me, Richie, whose energetic charm sprouted from knowing he was not the favorite child. He was desperate for a playmate and came looking for me whenever I was around. So Richie and I shot pool, slammed air hockey in his basement rec room, and even started playing tennis, another activity for which my parents sought formal training. I spent a whole summer at a tennis clinic in Central Park trying to be Björn Borg, but Richie beat me every time. He beat me at everything, but playing with him was still more fun than practicing piano.

Every Wednesday, I took a bus to the local music store in town for my hour of torture. Lessons took place in the back, past rows of shining guitars of all shapes and colors. As I clanked down on the keys, the instructor would eventually grow bored and start eating his supper, and it was always something delicious-smelling. Like a weekly tour of the Carnegie Deli, he brought salami on rye one day, stacked bologna on a hard roll another, and then tuna on white with a side of loud crunchy pickles. No matter what, he always had something better than my public school lunch and breakfast of menthol cigarettes stolen from a silver box at Richie’s house. I wasn’t really a smoker and only lit up when the morning school bus approached. Just before the yellow door swung open, I flung my cigarette to the ground and blew out a plume of minty exhaust as I boarded, hoping someone saw me. Unlike my friends, I wasn’t allowed to have long hair or wear torn jeans, concert tees, and Keds to school. I wore Earth Shoes, off-brand polo shirts, and khaki pants. I thought the cigarette would detract from my squareness, but it made me look like a smoky substitute teacher instead of a stoned Keith Richards. By 4 pm, I was jittery and starving as my instructor rustled foil, chewed, and slurped while barking music terms I was supposed to study: “Staccato! Tempo giusto! Molto allegro! Adagio!” These half-hearted performances went on for a few weeks until he’d had enough.

Having teachers call home was a common occurrence in my household, but my parents were paying good money for these lessons, and they were done throwing it away. I had disappointed them again. Not only was I the most defeated at tennis camp and a C- student, but now I was a failed musician too. Their dream of having a Beethoven-playing son was dashed for good. My luck finally turned around when my friend Jaime invited me to play piano for a jam session with his band Soul Solitaire. This is what I wanted all along: to be in a rock group. It was really happening.

Jaime was a naturally gifted musician and one of my best friends since fourth grade. His father was of the Woodstock era and had all the classic rock records, so Jaime’s foundation was built on Duane Allman, Jimi Hendrix, and Neil Young. His first guitar was a blonde Hondo Stratocaster knock-off. It looked real enough. The deal was, if Jaime showed he was serious about guitar, he would get a real Fender Strat by high school, but he already had all the dedication, perseverance, and talent required.

During an afternoon when Jaime’s parents were still at work, we smoked a few skinny joints before setting up on the backyard deck that faced a small patch of woods. Lead guitarist and vocalist Jaime was on his Strat, Chris on bass, Nick on rhythm guitar, Aaron on drums, and me on a miniature organ belonging to Jaime’s sister – my six-year-old cousin had the same one. Once plugged in, a little fan came on to propel a few octaves of mournful gasps through a mesh vent out the front. Because it was made for little kids, the organ was low to the ground, so I had to kneel to reach the keys. It didn’t matter. I was just happy to be in a band. With my keyboard miked up to a small amp, we were ready to rehearse The Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” off the Beggars Banquet album.

The first instrument of many an aspiring rocker, a reed organ. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Glogger.

The first instrument of many an aspiring rocker, a reed organ. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Glogger.

For a piece that requires an assortment of keyboards, guitars, and a samba orchestra’s percussion section, “Sympathy for the Devil” was a complex song for our junior high band. Nevertheless, Jaime was a natural arranger and knew how to fill in the sounds. That’s where I came in. I was expected to improvise the first two minutes of Nicky Hopkins’ piano part. I listened to the song a bunch of times but didn’t prepare anything like the other guys. It didn’t seem very “rock and roll” to be doing homework. Consequently, I was lost during rehearsal. Even if I had sheet music, I probably couldn’t decipher that level of detail. To get us through the beginning of the song, Jaime taught me three chords. “Come in on two. Okay now! Hit the next chord… now!” He kept count for me, but it wasn’t working. I couldn’t keep time. Then Jaime decided I should do the woo-woo parts of the song. All I had to do was contribute one well-placed chord for two-thirds of the song.

“I watched with glee [woo-woo]

While your kings and queens [woo-woo]

Fought for ten decades [woo-woo]

For the gods they made [woo-woo]

I shouted out [woo-woo]

Who killed the Kennedys? [woo-woo]

When after all [woo-woo]

It was you and me [woo-woo]”

And so it went with more than 100 woo-woos.

With the help of Jaime’s head cues, I slowly got the rhythm and was reaping the rewards from years of classical piano study. While beating out my chord, I added stage embellishments such as rocking the keyboard back on its legs, dancing from the knees up while pointing to my bandmates with my free hand in a show of solidarity and encouragement. “Yeah, man, you got it!” The first song was done, and I was ready to learn the chord for the next. In the meantime, I worked up quite a thirst.

I walked through the sliding door flying high – not from all the pot we smoked, but from the satisfaction of a solid performance. Like Billy Preston did for the Stones all through the 1970s, I brought my keyboard skills to complement the band’s sound without overtaking it. I was comfortable not being the center of attention and not having too much responsibility.

As I poured juice from a pitcher, I imagined my show business arc as a part of Soul Solitaire. We would rehearse, do some local shows, and move down to the city to get discovered. Then, who knows? My rise to fame would be a comeuppance for my stepfather and the two piano teachers whom I would not credit in my Grammy speech. People were finally going to realize that I was a rocker all along.

When I went back outside, I noticed my band members huddled around the little organ on short legs. Perhaps a blown fuse, or a spilled soda, or maybe Aaron dropped his cigarette on my knee cushion borrowed from the couch. As I came closer, I could see they were disassembling my keyboard station. The long extension cord that powered my instrument from the kitchen was needed elsewhere, and so was our only other microphone and amp. Jaime, our leader, and my friend from the old neighborhood had the task of demoting me to a hanger-on. I’m relieved he didn’t ask me to be a roadie in exchange for weed. I would probably be hauling crates to this day.

“Sorry, man, Aaron needs that mic,” he said. I wondered, indignantly, why he needed my mic when those drums were loud as sh*t already! I could barely concentrate on my keyboard part as it was. “He’s going to sing the woo-woo part, like in the song.” I was beginning to understand. Jaime was just trying to include me, but this band didn’t need a member who could barely land three fingers on the right keys. Not only could Aaron drum with all four of his limbs in rhythm, but he could sing at the same time. My talent went as far as posing in the mirror with a tennis racquet and pretending to play under bright lights like the guys in magazines. It was all gone – limo rides, leather pants, groupies, and easy money. I was washed up by seventh grade. All I could do was go back inside and play records until the rehearsal was over. But Jaime and I remained best friends until my family moved back to Manhattan.

After high school, Jaime honed his craft for years by playing the blues in New York City before packing up his guitar and moving to Italy. He didn’t stop at performing covers; he went on to write his own material, and nowadays, he makes a living playing Delta blues with his band iNNeRSOLe! throughout Europe. His love of the blues is authentic and flows naturally. He might not be well known, but as a composer, songwriter, musician, and singer, Jaime Dolce is in the same company as Hendrix, Allman, and for that matter, Lindsay and Hammerstein.

As painful as it is for so many young men to realize, most of us are destined to be lifelong spectators and never participants in making music. I’m sure I could start taking lessons again and probably learn a song or two, but that doesn’t make it art. My playing was always stilted and lacking emotion, and I had no desire to improve. On the other hand, Jaime took his lessons seriously. He loved to play, and practicing wasn’t a chore for him. In case expulsion from music school wasn’t enough of a cease and desist, Jaime ultimately freed me from the burden of playing ever again so I could enjoy listening even more. He also saved my parents from a future of humiliation and financial woe as they paid for my studio apartment, electric pianos, and lessons well into my 40s. Best of all, they would never have to hear me explain my joblessness at family functions with, “I have a job – my music.”