I first had the pleasure of becoming recently acquainted with Aston Sharman, when I stumbled upon his intriguing boutique, Vintage Technology Workshop, tucked away in the UK’s historic Barbican area in Plymouth (see header image above). A neighboring retailer had informed me of Sharman’s great engineering prowess and repair skills and that he had been a former engineer for Sony. I was particularly intrigued, as I had an old Sony Walkman which needed some professional attention. I had failed to resurrect it under my own steam, having only been able to replace the old belt, and although the playing mechanism was operating, my cassettes continued to produce a warbling and pitchy playback. Full of hope and promise, I soon returned to the shop with my beloved Walkman and sought out the man himself. Aston then performed an amazing repair for me, servicing the rollers, capstans, mechanism assembly and belt seating, and restoring it to its former operational glory.

Little did I realise just how extensive and far-reaching his working career stretched. Below is just a very small snapshot of some of his generous insights, and projects he has been involved in over the decades.

Russ Welton: Would you like to introduce yourself to our readers?

Aston Sharman: Certainly! I am a Sony-trained audio engineer, and latterly, a Panasonic/Technics-trained [analogue] and digital audio engineer, dating from the 1980s and 1990s, respectively. It’s safe to say that between the companies of Sony and Panasonic/Technics (Matsushita), somewhere in your house, there will be a piece of technology containing components from one of these companies, from the lowly capacitor up to integrated circuits.

Aston Sharman. Courtesy of Aston Sharman.

RW: How did your career develop into becoming an engineer for Sony?

AS: After leaving school I decided that electronics was the future, well at least for me anyway. I always found myself dismantling something or other around the house when I was little, so I thought it was long overdue that I actually learnt how to repair things properly. I enrolled in a compressed five-year college course for television and radio servicing, industrial engineering, et cetera and came out with a few choice degrees.

It was just a matter of luck that when I looked in the trade magazines for a job, a position at Sony had just been advertised and I had the right degrees needed for what they were looking for.

RW: What are some of your favourite Sony audio products and why?

AS: The TC-K950ES cassette deck. Very sexy looking, sounds like you're listening to pure velvet, and built like money was no object. The ultra-over-engineered Sony CDP-557ESD and CDP-X7ESD CD decks with their beautiful Burr-Brown DACs, and to a lesser extent the CDP-X777ES and CDP-X77ES CD decks with their 1-bit Pulse DAC processing, all looking like they were made out of unobtanium.

(Wikipedia’s definition of a pulse DAC states: "A Bitstream or 1-bit DAC is a consumer electronics marketing term describing an oversampling digital-to-analogue converter (DAC) with an actual 1-bit DAC…in a delta-sigma loop operating at multiples of the sampling frequency. The combination is equivalent to a DAC with a larger number of bits (usually 16 –20). The advantages of this type of converter are high linearity combined with low cost, owed to the fact that most of the processing takes place in the digital domain and requirements for the analogue anti-aliasing filter after the output can be relaxed. For these reasons, this design is very popular in digital consumer electronics…”)

Sony CDP-557ESD CD player.

I think we were talking about the WM-DD100 Boodo Khan Walkman the other day. A lovely piece of equipment, and horribly expensive at the moment on the second-hand market. However, there is a special limited-edition red anodised version that exists. I know, as I had the honour to service one back in the day. Supposedly there are only a handful of these “reds” out there.

The "Boodo Khan" name refers to one of the most famous indoor arenas of Tokyo [the Budokan]. The WM-DD100 was particularly prized by rappers of the era [thanks to] the massive headphones that were supplied [with the player].

RW: What’s your favourite Panasonic/Technics product?

AS: That prize has to go to the Technics SL-1210MkII turntable. The Technics SL-1210MkII was produced in dark charcoal for the majority of the world. America only had the SL-1200MkII which was silver.

It’s built like a tank, infinitely modifiable, impressively accurate, and surprisingly lightweight on the pocket. Although that last part might actually be becoming more difficult due to the demand outstripping the availability of un-thrashed second-hand ones. The modern reissues are, shall we say, less than stellar. They look nice, but their performance/cost ratio leaves a bitter taste in the mouth. (And a dent in the wallet.)

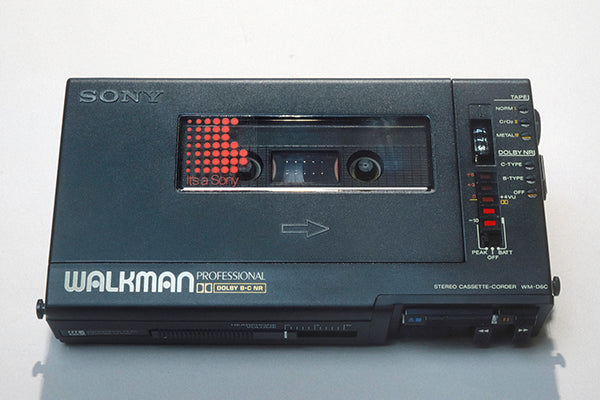

RW: Tell us about the old flagship WM-D6C Sony Walkman Pro and what made it special.

AS: The Sony WM-D6C was initially designed as a reporter’s portable recorder for travelling the world and handling a bit of rough and tumble along the way. This was the original version (the WM-D6); the “C” was later added due to the addition of Dolby C noise reduction and its new amorphous [tape] head. These propelled this little portable recorder (with its quartz-locked servo-controlled motor) to be the de facto weapon of choice for the audio-head looking for portable quality. Today the WM-D6C is highly sought after in good condition, and is now commanding prices akin to its original asking price (upwards of £1,000 in mint condition boxed). The thing is, if you replace the op-amps in the output stage, and re-cap the board, you are left with a Walkman that can come pretty close to a lot of audiophile decks.

RW: What were some of the most unusual projects and products you have been involved in?

AS: I think helping NASA with diagnosing and photographing [the way] tin whiskers propagate inside transistors has to be one of the most unusual projects I've had a part in.

It was found, rather unexpectedly, that certain electronics, and more importantly, transistors, that were encased in sealed tin enclosures, would propagate the growth of “live” tin whiskers, which would eventually short the component out, causing all sorts of problems down the road. This was of extreme importance to NASA, as a lot of their projects at the time were involving hardened circuitry encased in various metals including tin. So, as you might imagine, having something going horribly wrong on your super-secret-circuitry was a big no no. The webpage explaining this is still up on NASA's website here: https://nepp.nasa.gov/whisker/. In those days, [all we had was] film photography [to try and see what was going on], but [the webpage has] included lots more since.

RW: What were some of the most problematic component issues of the 1990s and 2000s as far as audio equipment was concerned?

AS: Leaking capacitors. Unbeknownst to most manufacturers of the mid-’80s through mid-’90s, due to a catastrophic error in the Chinese manufacturing plant that produced the majority of the capacitors for the world’s electronics, they accidentally put the wrong chemical into production, inadvertently destroying countless of pieces of audio equipment over the years. To this day engineers across the world are still trying to correct [the aftermath of] the problem.

Early lasers in the CDP-101, the first CD player to be produced by Sony, were, shall we say, a bit unreliable. The unit could overheat, burn out and generally misbehave unless absolutely set up to perfection. That and the fact that the unit could run so hot it would quite literally unsolder its parts.

RW: What are some of the most significant changes in audio design you have experienced as an engineer?

AS: I think the transition from full analogue audio design to digital signal processing [DSP] technology was an important (if not somewhat floundering in its early stages) step in the right direction. Pure analogue audio design requires exquisite forethought and dedication, using all of the skills of a design engineer to make sure that there is absolutely no colourisation of the audio chain. Yet while this is perfectly possible, it was only to be found incorporated into the very best of the best.

However, much in the same way that Triple-A computer games, (ones with massive development and marketing budgets and often classed as blockbusters) such as Grand Theft Auto 5 which has about 30 different updates available to patch out the bugs, are fixed "after the event," audio stages can now be tuned not by the engineer, but by either firmware upgrades or simple algorithmic changes in software. This is a game changer for the audiophile; now you can have a perfectly flat 20 Hz – 20kHz [frequency response from your electronics] at a touch of a button. Even my own basic Sony audio ES Series surround sound amp has a plug-in microphone to tune the room for acoustic loveliness. [However], Apple AirPods spring to mind as an example of [experiencing] an unexpected and not necessarily welcomed frequency response change due to firmware updates.

I think a more recent innovation that impresses me is AI stem-splitting algorithms. Using artificial intelligence and sophisticated computer learning, [engineers have] been able to create software to separate the vocals, drums, guitars and other instruments [in a recording] for remixing, [creating] multichannel surround sound, and remastering from recordings that didn't have multichannel audio recordings made in the first place. One example is Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of The Moon hybrid multichannel SACD. Peter Jackson’s [documentary] The Beatles: Get Back used this technology to pull out the voices from the recordings to hear what the Beatles were saying, as they had a tendency play their instruments to drown out their conversations for privacy. An example of AI stem-splitting can be found here: https://www.splitter.ai/

RW: What does the end of the dominance of Japanese audio manufacturing mean for you and the rest of the world?

AS: Sadly an end of an era, in which, in my opinion, during the 1980s and 1990s some of the greatest audio equipment was lovingly created. [Look at some of] the outrageous steps [manufacturers] took to separate the power supply and audio sections from interfering with each other, like the Sony “Gibraltar” chassis design and copper-plated steel and solid copper circuit bays. A feast to the eyes, and a banquet for the ears.

With [so much] of Japan now taken up by business headquarters, and [with] offloading manufacturing production to both Malaysia and Taiwan, no longer can you rely on the superb craftsmanship of the Japanese. That's not to say that the quality is terrible, but that little touch of Japanese precision has been lost along the way, in my opinion.

RW: What does the future hold for service engineers, and designers of new products?

AS: I'm afraid the era of the service engineer is in rapid decline. What I’m trying to say is that there have been no educational courses at college that teach individuals in the art of repairing anything for at least 20 years or so in the UK. No longer are there engineering courses that involve servicing in general, and indeed there haven't been for many decades. All the existing engineers are, myself included, getting a bit long in the tooth and sadly, over the last few years some of the greatest minds have been lost to the pandemic. If something isn't done soon to address the situation, the future of the repair industry is in jeopardy. There will be nobody left alive soon (think 20 years) who will be able to keep your (then) vintage stuff working. Yes, you will always have dabblers, but I'll leave them to the Darwin Awards.

As for the up-and-coming talented creators of new and as-yet-unseen products, the mainstream industry seems to be obsessed with mobile technology. This is all fine and dandy, but is mostly just a minor iteration of the previous generation of technology. Innovation comes from thinking outside the box, not just redesigning the box.

RW: Tell us about some examples of how the human touch and control is still essential for product manufacturing.

AS: Canon’s lens manufacturing plant is a good example of why the human element should never be neglected. The lens grinding masters at Canon have the ability to feel when the machine is not grinding a lens to perfection, and just by applying pressure on the machine in a certain manner, are able to correct the inaccuracies therein. Thankfully, this innate talent is being passed down to the next generation of apprentices in the factory.

RW: What advice, which is perhaps most often overlooked, would you give to audiophiles to help them improve their stereo sound?

AS: I think the art of listening, and I really mean that when I say art, is when you, the audiophile, gets the pure emotional joy that you're expecting from the piece of music you're listening to out of your hi-fi setup. Now, I realise that sounds like a strange thing to say, but if you know what you're looking for in a piece of music, and it's not there, that is when your journey begins for a better understanding of what it is you want out of your equipment. Now, whether that means auditioning different pieces of equipment to attain that feeling you strive for is ultimately for you to decide. Every individual is looking for their own acoustic nirvana. What I'm saying is that until you've heard your own personal version of audio perfection, you first have to use the art of listening to decide for yourself what is missing and act upon that.

To that end, you need to decide what kind of audio chain you are looking for. [For example,] are you looking for a flat response all the way through, or are you are looking for something different? Only you can answer that, but you'll know it when you hear it.

Header image: the Vintage Technology Workshop. Courtesy of Aston Sharman.

Aston Sharman. Courtesy of Aston Sharman.

Aston Sharman. Courtesy of Aston Sharman.