The last episode in this series (in Issue 156) discussed the technological and aesthetic shifts in the record cutting lathe manufacturing industry that began in the late 1970s and concluded in the 1980s, with the ultimate demise of the industry. (Believe it or not, it has not been possible to purchase a new professional disk mastering lathe, manufactured in large numbers by a company of more than two employees, since the 1980s!) Up until that point, things had been somewhat conservative. In this episode, we will examine what was perhaps the single most well-known, well-remembered, well-documented, widely-used and ridiculously overhyped disk recording lathe of all time! While it was a very capable performer, it was also cleverly marketed. It filled a market gap that had existed for some time, clearly demonstrating the differences in mentality that existed in this industry between the US and Europe. In fact, this market gap had begun to be filled in Europe much earlier, but by the early 1970s, the West was won, and it wasn't by Led Zeppelin this time!

Mike Papas of XL Productions, Ashbury, Australia

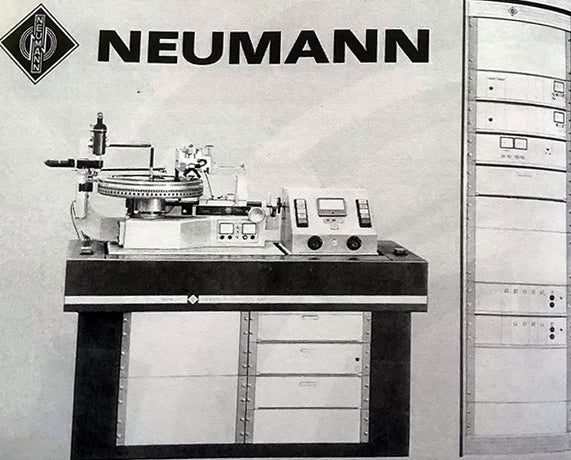

Mike Papas of XL Productions, Ashbury, AustraliaThe machine in question was the Neumann VMS-70, a complete, turnkey and highly automated system that conveniently eliminated a lot of the guesswork that had traditionally gone into purchasing, setting up, and using a disk mastering system. The VMS-70 set a new standard in the industry, and became the world's most popular lathe. Not the most popular by numbers sold; this would have been one of the primitive monophonic record-cutting machines once found in every radio broadcasting facility. The Neumann VMS-70 did not actually sell anywhere near that many numbers. But it did become the most commonly encountered lathe in commercial disk mastering facilities during the entire stereophonic era. It is probably safe to say that during the stereophonic era and up to the present day, more master lacquer disks have been cut on a VMS-70 than on any other lathe ever made. Still, only about 500 of these were ever produced, with much fewer surviving today. But, this is a lot, considering that the world has never had 500 professional disk mastering facilities operating at any one time! This has made the VMS-70 highly sought after to this day, and perhaps the most widely discussed lathe in the media and on the internet. In fact, its dominance in all mastering-related articles and discussions has led some people to believe that this is the only lathe that can cut "modern" masters, even though the Neumann VMS-80 (see Issue 153 and Issue 154) that superseded it, as well as the competing L.J. Scully LS-76 (covered in Issue 155 and Issue 156) were way more modern in every sense, right down to their aesthetics. As a result, the price for a Neumann VMS-70 in the used market nowadays can easily be mistaken for the telephone number of the person selling it!

The Neumann AM 31 specifications, from a Neumann brochure of the time.

The Neumann AM 31 specifications, from a Neumann brochure of the time.The general approach was very similar to the early Western Electric lathes. The early Neumann lathes had a sturdy machine tool-type bed, a substantial vacuum platter, a horizontal slideway (for the carriage that transported the head across the blank disk surface) that ran under the platter, a carriage arm that held the cutter head and its suspension unit above the platter, and an accurate leadscrew mechanism. The lathe had enough space to allow the mounting of any cutter head of the past, present and future, and a high-performance floor-standing motor (supplied by Lyrec in Denmark), that directly drove the platter via an oil-coupler, to reduce rumble and noise. The latter was inspired by the much more advanced, but also much more expensive to manufacture than the Kingsbury bearing fluid coupler used in the early Western Electric lathes.

The US market consisted of various individuals and small companies, who were very much used to making stuff on their own, modifying equipment, mixing and matching and generally using whatever means were at their disposal to set up a sound recording studio that they could work in. It was therefore common for someone interested in building up a disk recording setup to purchase a lathe from Scully, and a cutter head from Presto, Olson, RCA, Western Electric, or Haeco, and drive it with a McIntosh amplifier, while making their own equalizers from scratch. They often had to make custom parts, and they needed to be able to figure out what would work and what wouldn't. There were no guarantees of compatibility or good results with such an approach, and it took considerable skill and knowledge to put together a system that would be capable of competitive sound quality. But, for those who were able to do that, the sky was the limit as to how their system could be set up. This was not limited to disk recording and mastering systems, but was the general approach in sound recording technology, and continued in a very similar manner well into the era of magnetic tape recording. In Europe, this approach was not very popular and in fact was often frowned upon. It was felt that only a well-known manufacturer should have the authority to decide how a disk recording system should be set up, so the manufacturers would either develop all parts of the system in-house, or they would partner with other established manufacturers to supply a complete turnkey system that was guaranteed to deliver a certain performance.

Modifications or any form of tampering by the user were very much discouraged.

The Neumann VMS Special, based on the AM3 2b mechanical assembly, with fancier electronic bells and whistles.

The Neumann VMS Special, based on the AM3 2b mechanical assembly, with fancier electronic bells and whistles.To get a better feeling for this, imagine you are looking to purchase a car, but nobody sells complete cars! You need to purchase the frame from one company, the engine from another, the transmission from a third company, the differential from a fourth, suspension from a fifth, steering from a sixth, and the body from elsewhere. However, maybe the body would not necessarily fit the frame, so you might have to do some cutting and welding to get it to bolt up. You would probably have to make your own engine mounts, figure out what torque converter would be a good match for the drivetrain, decide on the appropriate axle ratio, and so on. This is what the disk recording industry looked like in the US up until the 1960s. Europeans tended to prefer an approach similar to how the automotive industry works nowadays: just sell me a car that works. I'll take the red one, thank you. This is exactly what Neumann made possible. Not only did this prove very successful in Europe, but it also won over the US market and gradually shifted it away from the DIY mentality towards the "complete system" philosophy.

The Neumann VMS-70 system, the final version of this lathe bed design.

The Neumann VMS-70 system, the final version of this lathe bed design.There are parallels here with consumer audio equipment. In the early days of gramophones, it was common to purchase a complete self-contained unit, with a platter, hand-cranked drive, sound-box, horn and cabinet. When the electrical era arrived, it brought "consoles," which consisted of a radio receiver or record player, with a built-in amplifier and loudspeaker built into the same cabinet. But then the specialist high fidelity market evolved, where "separates" were offered, and the enthusiast could freely mix and match any record player with any preamplifier, power amplifier and loudspeakers they thought would offer better performance. Naturally, not everyone was qualified to put together a good system, and many bad choices have been made through the years, along with many outstanding ones. Besides, even in the realm of automotive technology, imagine wanting to enter competition motorsports, but only being limited to turnkey vehicles as offered by the established manufacturers. It would probably make for a rather boring race...!

Header image: The "pitch box of a Neumann VMS-70 lathe, from where the recording pitch could be monitored and adjusted. A couple of motors and a differential lived under this box, driving the leadscrew of the lathe, which would advance the carriage, suspension box and cutter head across the lacquer disk.

Photo courtesy of Greg Reierson of Rare Form Mastering, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

0 comments