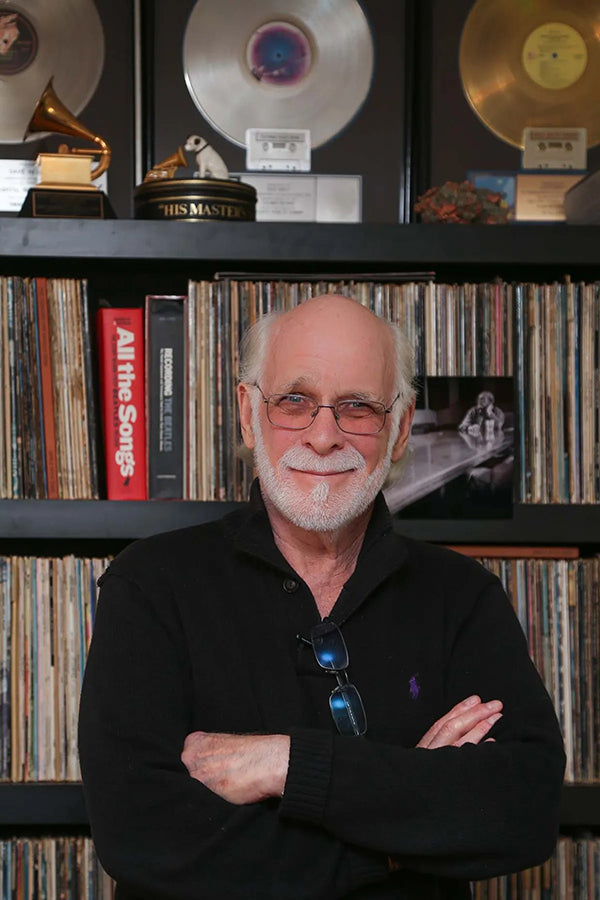

David W. Hewitt is one of the pioneers in designing remote multitrack recording studios. He and his mobile trucks recorded thousands of concerts from hundreds of artists across the United States and abroad, including Neil Young, Barbra Streisand, Simon and Garfunkel, David Bowie and countless others. We interview him here.

John Seetoo: You have recorded a large percentage of some of the most iconic live concert albums in rock music history. Many live albums actually contain overdubs that were added to the concert tracks because the artists wanted to correct wrong notes and other imperfections. Sometimes, this can result in an error-free but less inspired recording. Are there any live records that you recorded that blew you away when you were there in the moment that you later found had parts replaced, and made you go, “if people only heard how amazing the original version was?”

David W. Hewitt: I have found that my perspective [has] changed. In a business where you may record a rock star today and an opera star the next, I know my memory will be colored by the whole experience. The city, the venue, the audience…some performances may be stunning that night and [then sound] so-so with even the best remix.

The most powerful live performance I can remember is The Concert For New York City after the World Trade Center attacks. [the concert took place on October 20, 2001 – Ed.]

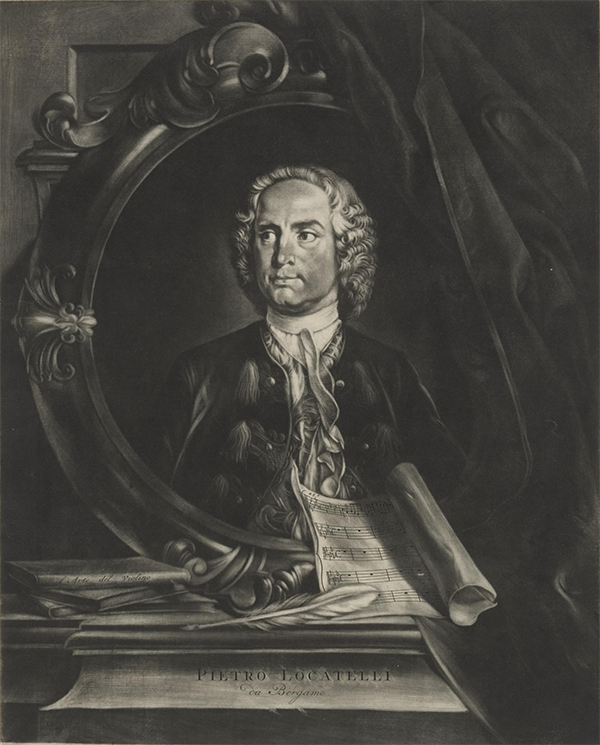

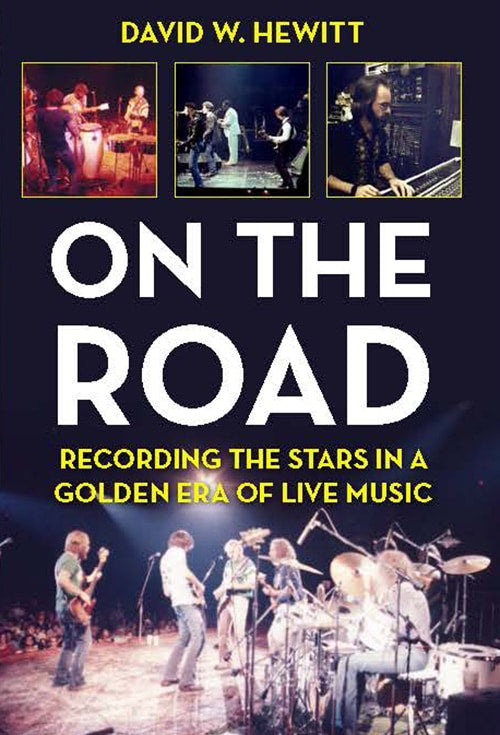

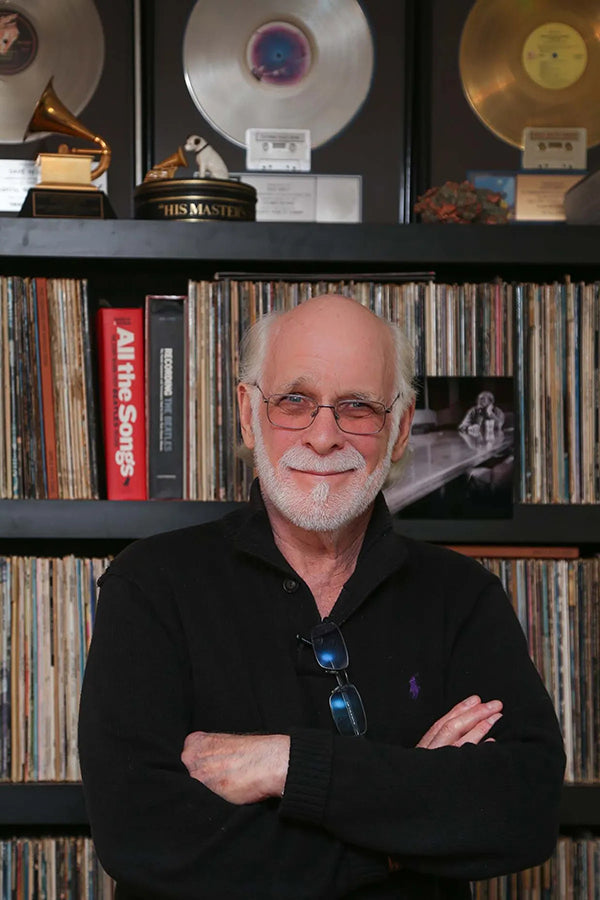

Here’s an excerpt from David’s book, On the Road: Recording the Stars in Golden Era of Live Music (reviewed in Copper Issue 170):

I have engineered many shows going out live to the world, but waiting for this opening act was the most highly charged I have ever felt. We did not get a rehearsal for David Bowie’s opening song and my hands were on the audio faders waiting to see what he would do. I don’t recall who did the introduction, but as the huge opening applause died down, a lone spotlight shone on David Bowie, sitting cross-legged on the lip of the stage. The audience was quietly mystified by the bare solo setting.

He started by playing a simple intro on a little keyboard, almost a calliope sound, and then began gently singing Simon and Garfunkel’s “America.” When he got to “Walked off to look for America,” it brought a swell of emotional response, as they realized where this was going. Of course, in the next verse is “I’ve gone to look for America.” Such a brilliant, understated but perfect statement, coming from a British immigrant to America. The repeated chorus of “they’ve all come to look for America” brought the house down.

He then paid tribute to his local ladder company: “My fellow New Yorkers…it’s an act of privilege to play for you tonight.” Just as “America” was a brilliant selection for the opening song, Bowie launched into his song “Heroes” for the coda. It was the perfect tribute to the first responders on 9/11, played at full volume with his electric band.

JS: While your mastery of recording on the fly in a remote truck became your specialty, what projects have you worked on in the studio, either at Record Plant Studios where you got your start or elsewhere, where your skills came in handy and in which you were particularly pleased with the final result?

Another question: as a remote truck recording engineering specialist, you were tasked with capturing the entire performance. On average, how much would you say of what you recorded came from the live sound mix from the front of house (FOH) console, and how much came from your own mics?

DWH: We always recorded directly from [our] individual microphones, not the front of house mix. Modern professional touring sound systems own quality mics, and tune their FOH and monitors to them. [But] I always tried to make their mic selections work for the recording, if possible. Often those decisions would be negotiated with the producer, the band and their sound mixers. I could of course add my own mics without replacing theirs.

We used our own mic splitters with Jensen transformers and added our own mic choices where possible. Additional audience and ambience mics were always necessary.

In live video broadcasts, any [permission to use] the live FOH mix would be up to the TV mixer and the producer in the video truck that feeds the broadcast. It’s always wise to have backup for live broadcasts.

JS: When recording, how often would you change EQ settings as the music printed to tape to get a better recorded sound, or did you leave things flat and printed as it came from the live house engineer?

DWH: We are talking about EQing our mic splits and not the FOH mixes here, yes?

I create my own mix in the remote truck. My decision [on whether or not] to change the EQ depended on the mission: is this multitrack recording going to a known client who will want to do their own EQ? In a case where it’s going to say, Eddie Kramer [recording engineer for Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones and others], I would only clean up the obvious grunge! He will do his own magic!

For the live stereo mix that’s going out [to the audience], my API or Neve consoles [were able to] EQ the monitor [mix], and not the [mix being] recorded. There I will use what EQ and effects seem appropriate. Especially a Neve 33609 [compressor/limiter] or my old API 560 equalizers.

JS: Would you characterize your role in overseeing the recording of a concert event in any of your fleet of remote recording trucks comparable to when Record Plant engineer Roy Cicala would sometimes engineer sessions himself, but more often would just oversee operations in a managerial role and occasionally step in when needed?

DWH: Well, my “fleet” of remote trucks never got beyond two of my own, but I was on good terms to hire other worthy trucks, like Chris Stone’s LA Record Plant’s trucks, Guy Charbonneau’s Le Mobile, and Randy Ezratty’s Effanel trailer.

I was also able to find great ones overseas. In England I used the Manor Mobile and others to record my friends Hall and Oates at Wembley Stadium, for Sony Music conventions at The Queen’s Gleneagles golf course in Scotland, on Yoko Ono’s tour in Budapest, Hungary, for the Eagles in Melbourne, Australia and Olivia Newton-John in Sydney, Australia, and for the Rolling Stones in Tokyo. Oh yeah, [I also recorded] the Rolling Stones at River Plate Stadium, Buenos Aires. The Havana Jam in Cuba is way too long. Look in my book in chapter eight!

JS: At any given concert, it seems that you would have to be ready to assume any number of hats, including chief recording engineer, electrician, troubleshooter, and any number of other positions. Were there any projects in which you suddenly had to step in as the chief recording engineer and were unfamiliar with the artist or the genre of music? If so, what were your workaround solutions to being put on the spot like that, and how did the project(s) turn out?

DWH: When I started out In the live recording business, we were called mostly for popular rock bands, star singers, some jazz, but very little classical. On Jan 25, 1974, I was booked to record a classical pianist at Carnegie Hall for RCA Red Seal Records. Those were always strict union engineering gigs, so I was shocked when I arrived to find they were on strike! The renowned [classical music] producer, [John] “Jack” Pfeiffer, was unfazed. He smiled and said, “looks like you are in the chair.” Gulp…

The artist was Jorge Bolet, a famous classical romantic pianist, playing solo. Jack reassured me that he had the scores and would conduct me! Bolet is a very powerful pianist, opening with Bach and Chopin preludes and [playing] endless encores. I needed every cue Jack could give for the huge dynamic range! That old DeMedio console sang! So I survived my classical piano initiation thanks to Jack, who became a great friend and client.

[Right after that] I drove over to record the Bee Gees at Avery Fisher Hall (now David Geffen Hall).

Like so many recordings [I’d done], I never heard the finished product until I happened to find a copy in an antique book store 48 years later. A friend, who is a classical pianist, informed me that Bolet’s Carnegie Hall concerts and that recording had renewed his career for many years. It’s on RCA Red Seal ARL2-0512, a double album – good luck finding this one!

JS: You have cited several situations, such as Neil Young’s first Unplugged concert (in 1993) and with Pink Floyd, where the artist didn’t like a performance that was recorded and refused to let them be released. Were there any projects you worked on where this happened and you heard other subsequent live releases from those same artists that, in your opinion, should have been swapped for the shelved recordings you engineered or oversaw? What stood out in those performances for you that you think the artist(s) overlooked?

DWH: There is one missed recording that still haunts me. In 1979, which was still during the Cold War, Bruce Lundvall, president of Columbia Records, negotiated a deal to put on and film several concerts of Cuban and American musicians playing in Havana to promote peace. Miraculously, it was approved, and I built a complete portable recording system and flew it to Havana on a war surplus C-46 transport. We still couldn’t travel to Cuba on American flights.

There were great American artists like Steve Stills and Weather Report, plus Cuban stars Irakere and Fania All Stars – and the headliner, Billy Joel, who was instrumental in getting this through the political obstacles. Few people seem to know that Billy’s Jewish grandparents fled Nazi Europe to Cuba, where they lived for several years before getting passports to America. There were still family relatives living there.

So, Phil Gitomer and I built our portable recording studio for the Columbia engineers and interfaced with Jack Maxson’s Showco sound system. Everything was going well, until I was firmly told by Billy Joel’s management that we were not to record his performance! They stood there as we removed the tapes from all the recorders.

There was a lot of finger-pointing as to who made that decision and why, but many people, including me, thought it was Billy’s greatest performance ever.

Need [another example]? For Live Aid, there was no multitrack recording! The biggest recording mistake [you can make] is not to record!

JS: Can you compare the challenges in obtaining great live multitrack recordings in small, cramped venues (like The Bottom Line, where you recorded Lou Reed’s 1978 Live: Take No Prisoners (one of a number of your recordings for which I was in attendance!) versus outdoor stadiums (like the Rolling Stones’ Voodoo Lounge tour), in terms of choice of microphones and outboard gear, and having to deal with isolation and crosstalk between microphones and so on?

DWH: Well now, that Lou Reed recording is a real case in point. My fellow Record Plant NY engineer Rod O’Brien recorded it on my remote truck and mixed it at Record Plant. The producer and record execs loved it.

[For] a relatively small venue like The Bottom Line, we [decided to] use a few shotgun mics off the stage and several Neuman U87s off the elevated house mix balcony. But…Lou had been fascinated by using the [then]-new ambient binaural head mics in the studio and decided to use them at this recording. Several were hung just under the balcony.

Lou wasn’t around for the final mix and upon hearing it, decided to take the master tapes to Germany and remix them using only the binaural head mics. Lou and the binaural mics owner loved it. Record buyers, not so much. You decide.

JS: Were there particular challenges that you recall from when artists started to require recording in multiple formats simultaneously, such as running digital Mitsubishi or Otari recorders along with Studer analog multitrack machines? The amount of space required for the tape machines, the tape storage, and the differences in headroom between analog and digital recorders are just a few of the considerations that come to mind, but I am sure you had to handle much more. Has using Pro Tools or other DAW (digital audio workstation) software changed the paradigm significantly for you?

DWH: Well at least the changes in multitrack formats were fewer than all the [changes in] mixdown formats! I only had to deal with 8-track Scully and 16-track Ampex MM-1000 [analog decks] at Regent Sound Studios in Philadelphia in 1971. When I started working in the “White” remote truck at Record Plant New York, it had a pair of MM-1000s. Interestingly, they had been prototype 24-track machines. The [track] arming switches were there, but [the decks] only had 16-track heads. And they only ran at 7-1/2 or 15 ips (inches per second)! No 30 ips, and if the client wanted Dolby [noise reduction] I had to beg the studio or rent it. There were not that many equipment rental companies back then. Not to mention no room in that tiny truck!

When I finally built the “Black Truck” in 1978, we had room and bought a pair of Ampex MM-1200s. They received many mods over their lives, thanks to chief engineer Pen Stephens, and Paul Prestopino.

After we crashed the Black Truck, [more on that in Part Two], Chris Stone graciously rented me one of his older remote trucks. We used our black Ampex 1200s until I built the “Silver” tractor trailer. I then bought a pair of Studer A-820 [decks] with Dolby CAT-280 SR [noise reduction] cards. Those were consecutive-serial-number twins. Engineering art!

I did have experience with the pioneering 3M 32-track digital recorders, I admired their bravery, but not their reliability. Later Mitsubishi 32-track digitals were better, but couldn’t compete with Sony.

As the early Sony PCM-3324 [digital recorders] arrived, I had a partnership rental pair, and then the PCM-3348s appeared. Studer [then] designed their own D827-track digital recorders. I believed they sounded the best of all, and spent hundreds of thousands to buy a pair. Don’t ask…

Of course, Pro Tools and other cheaper computer systems were now arriving. They were not very reliable in the beginning; I could tell you some hair-raising crash stories! We always backed them up with tape.

In our last White remote truck, we had both Pro Tools and a pair of Nuendo hard drive recorders with Apogee A/D and D/A converters. I believed they sounded better.

Part Two of this interview will appear in Issue 179.

For more stories, read David W. Hewitt’s book, On The Road: Recording The Stars in a Golden Era of Live Music, available at https://davidhewittontheroad.com and from online retailers.

Header image of David W. Hewitt courtesy of David Reiter.

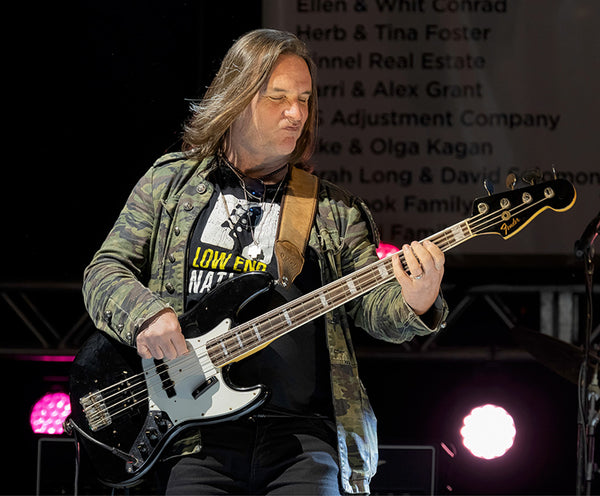

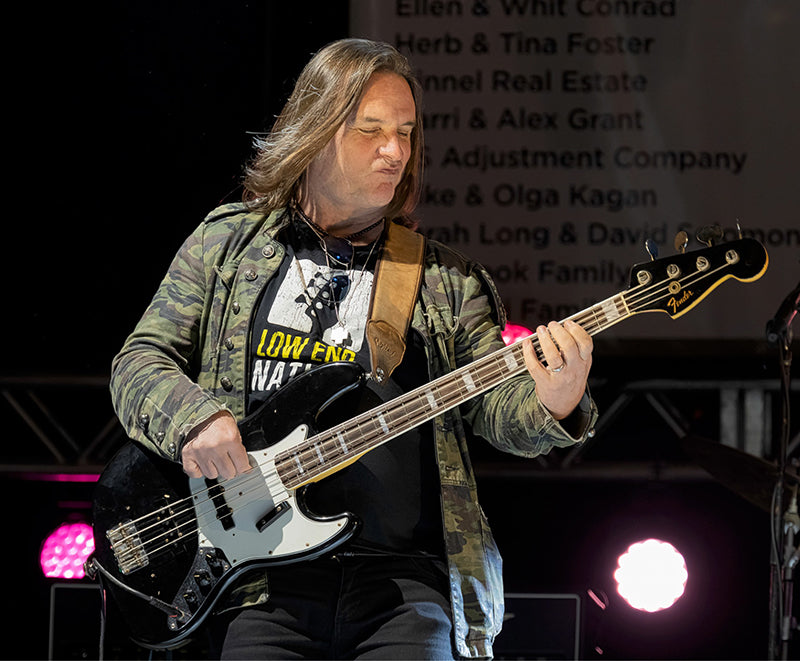

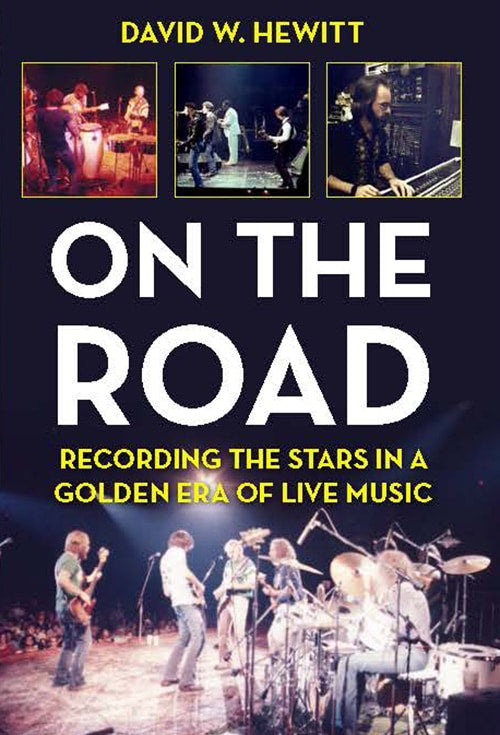

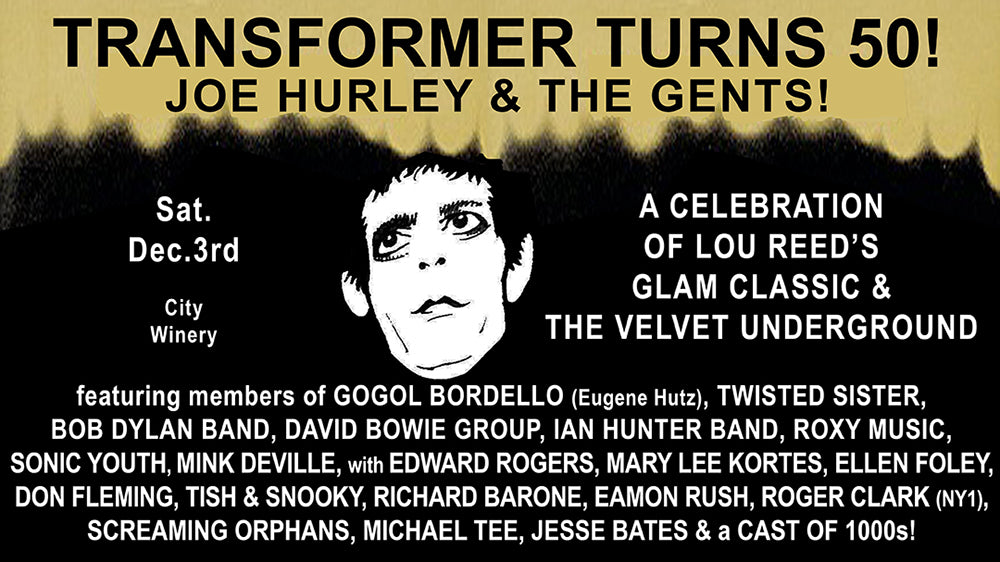

The band: Don Fleming, JF, Joe Hurley, Steve Holley (obscured on drums), Edward Rogers, Sal Maida, Stan Harrison, and Kenny Margolis. Courtesy of Melani Rogers.

The band: Don Fleming, JF, Joe Hurley, Steve Holley (obscured on drums), Edward Rogers, Sal Maida, Stan Harrison, and Kenny Margolis. Courtesy of Melani Rogers.

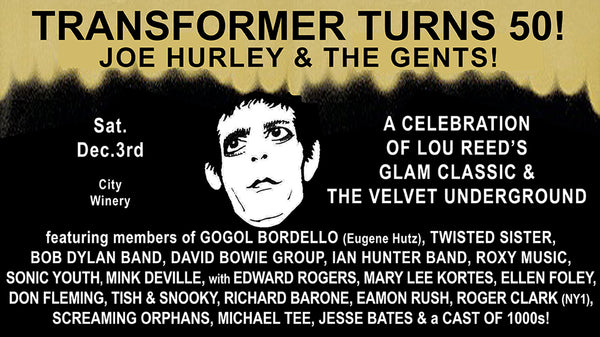

Part of Lou Reed's personal record collection, on exhibit at the New York Public Library. Courtesy of Larry Jaffee.

Part of Lou Reed's personal record collection, on exhibit at the New York Public Library. Courtesy of Larry Jaffee.

Teac W-1200 dual cassette deck.

Teac W-1200 dual cassette deck.