Having visited the Great British disk recording industry in our last episode (Issue 177), it is now time to ask where it all began. How did they start eating beans on toast, and why would anyone think that manufacturing a bonsai car in large numbers would be a good idea (not to mention the millions of people who actually bought them)?

Or better, we could explore the humble early beginnings of sound recording instead. Where did it all start, and what were the earliest machines like? Who made them, and what were they thinking?

I will start from the very beginning, highlighting the evolutionary milestones that led to the invention, development and refinement of the disk recording lathe from the dawn of time to the present day. First came the big bang, then dinosaurs, some other unimportant stuff, and a few thousand years down the line, came sound recording, finally bringing some sense to this world. (I really tried to offer an unbiased perspective…and failed!)

The concept of sound recording dates to the middle of the 19th century, developed by what we would now consider over-skilled individuals, in different parts of the world, in dimly-lit, unheated sheds and workshops, before electricity was a thing. It escalated rather rapidly into one of the largest industries of the past century, all the way to luxury goods marketed as being made from hair collected from a unicorn’s posterior under the full moon.

Sound recording did not start with the disk medium and in fact, it did not start with a medium that could be reproduced. In 1857, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville invented the Phonautograph, a device that could record sound on paper or glass by drawing the soundwaves, but offered no means of playing it back again as sound. In 1877, Charles Cross described a device that could record sound on a cylinder using a screw, but hadn’t actually succeeded in building one yet, when Thomas Edison came up with the Phonograph. The Phonograph was the first invention that would not only record, but also subsequently play back sound. This essentially means that our industry will be celebrating 146 years of existence in the new year. In 1887, Emile Berliner joined the game with his own cylinder recorder, but in 1888 decided to use a flat disk as the recording medium, creating the disk record.

The very first disk recording lathe in the world was therefore built by Emile Berliner. It was rather crude, but the idea was out there, and it would see constant refinement for many decades to come.

Columbia Records started in 1888 as well, followed a year later by the Gramophone Company in London. This was the acoustic recording era, meaning that all recordings during this time were conducted without using electrical equipment. There were no microphones, no mixing consoles, no amplifiers and no electric motors to power the lathes. This was not a situation particular to the sound recording industry. Manufacturing during that time did not rely on electricity and electric power was not widely available. Early electric motors were prohibitively expensive, and it was unheard of for multiple motors to be used in a factory to power the machinery.

At the time, a typical factory would have a single source of power, typically a steam engine, which was sometimes shared by neighboring factories. The steam engine would drive a long shaft spanning the entire length of a building, fitted with multiple pulleys, on which flat leather belts would run, with a tensioning system that would allow the belts to be slid on and off the pulleys as needed. The long shaft, typically situated overhead, right under the ceiling, was called a line shaft. The various machines in the factory were all powered by the same line shaft system, which would always remain in motion. The individual machines could be started and stopped by engaging or disengaging their belts while the line shaft was running. There were no belt guards or emergency stop buttons, and pressure vessels were not known to be the safest things to sit around. OSHA (the Occupational Health and Safety Administration) had not been yet been created!

This kind of setup was not suitable for powering sound recording equipment. Line shaft systems were only used in large factories, where a lot of power was needed for powering hundreds of machines. They were very expensive, noisy, not at all portable and worst of all, did not run at a steady or even predictable speed. Small workshops that only had a metalworking lathe or a drill would often power these machines using a treadle, in a manner similar to early treadle-operated sewing machines. Unlike a sewing machine, however, it took quite some muscle to run a metalworking lathe in this manner. To be able to do that while actually machining was quite a feat, as anyone who has ever tried to operate a treadle-powered lathe will have quickly found out. Yet, this was exactly the environment in which early disk recording lathes were made.

The very early units were simply hand-cranked, but it was impossible to maintain speed stability in this manner, so more elaborate mechanisms were developed. In the mid-1890s, Eldridge Johnson of Camden, New Jersey, was commissioned by The Gramophone Company and their associates in the US to develop a spring-powered and mechanically-speed-governed drive system, similar to what most people associate with gramophones nowadays. This became one of the two established ways to power such devices prior to the shift to electric motor in the late 1920s. The other method involved a weight -driven mechanism, again utilizing a mechanical speed governor.

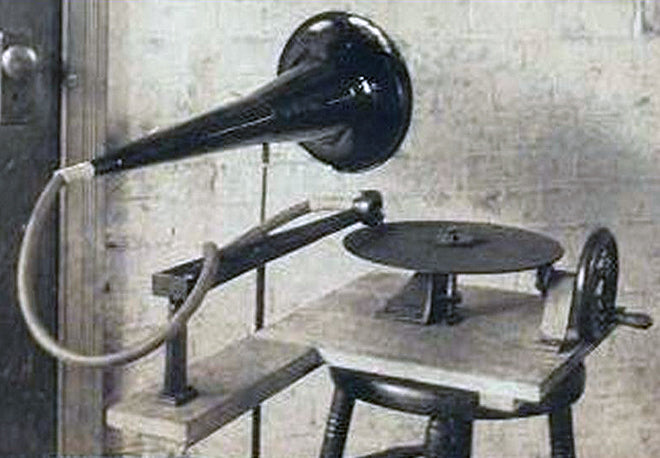

There is very little information available regarding the exact construction of the early disk recording lathes used commercially by the record labels of the time for their acoustic recordings, and very few photographs. The basic design principles were shared among the machines. They all had a platter driven by one of the two purely mechanical drive systems. They all had a sound box consisting of a thin glass diaphragm, and a horn to “collect” the sound. The diaphragm would vibrate with the sound, imparting this motion to a cutting stylus that would wiggle while cutting the groove on a blank disk. Shapes, sizes and degree of sophistication would vary greatly, but the general operation was the same.

The early disk recording lathes seen in the limited photographic documentation that survives appear to have been very crudely made, mostly out of wood, with very few accurately machined metal parts.

In 1909, an experienced machinist by the name of John J. Scully made his first disk recording lathe, while employed by the Columbia Phonograph Company, where he was contributing improvements to the Dictaphone. He left Columbia in 1918 and went on to briefly work for the General Phonograph Corporation, before establishing the Scully Recording Instruments Corporation in 1919 in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The early Scully lathes were weight-driven and were a game-changer in terms of design and build quality. In these early lathes, it was the platter and drive assembly that would advance under the stationary soundbox. Scully lathes were made of machined metal, in the tradition of proper machine tools, for which Bridgeport was well known, having been a hub for the development of the machine tool industry in the US. The Scully lathe was the first disk recording lathe truly worthy of being called a lathe.

In 1924, Western Electric purchased a Scully lathe, which they equipped with their first cutter head for electric recording. Western Electric demonstrated and licensed their system to Columbia and the Victor Talking Machine Company, prompting Scully to update the design of their lathe. The changes included an electric motor, a stationary platter, and a carriage advancing over the platter. In the second half of the 1920s, the acoustic era came to an end and electric recording took over. Scully had set the bar very high and dominated the disk mastering market for several decades, keeping their high-quality standards intact until the end. John Scully can be credited with introducing the first properly engineered solution to the problem of developing a disk recording lathe, utilizing his skills in machining and industrial manufacturing to create a machine that brought new standards to the industry and pointed to the direction things would be heading in the decades to come. Nevertheless, I believe that fewer than 10 acoustic recording lathes were made by Scully in total. His son, Lawrence J. Scully, joined the company in 1933 and carried on the torch.

Bernard MacMahon and Nick Bergh with the Western Electric Recording System in The American Epic Sessions. Courtesy of American Epic, © 2017 Lo-Max Records Ltd.

The price of the early acoustic-era Scully lathe is not known, but the first electrical-era Scully lathes cost approximately $30,000 in modern dollars (adjusted for inflation), not including the cutter head, cutting amplifier rack and several other pieces of equipment that would be needed to be able to use the lathe. The later model Scully, with manually adjustable, electronically variable pitch would be priced at $90,000 in modern dollars, again not including anything but the bare lathe. This sector always had a pretty high entry level, but considering the materials and level of craftsmanship that went into these machines, their prices were quite reasonable.

If you don’t believe me, try to make one!

I have!

At least, by the time the electrical era had arrived, it was possible to buy a disk recording lathe and the associated equipment to get started. In the early days of acoustic recording, if you wanted to get involved in sound recording, you had to make everything from scratch!

One thing is certain: We owe the existence of sound recording to the creative, crafty and resourceful individuals who dared to dive into the unknown, into uncharted waters, to develop something nobody had done before. Similarly, we owe its continued development and refinement to those who dared to take it a few steps further, believing that there is room for improvement. There always is.

It just takes someone to believe in it and dare to do it.

Header image: from the documentary American Epic, a restored Western Electric recording system with Western Electric recording rack. Scully Lathe, and Western Electric microphone. Courtesy of American Epic,© 2017 Lo-Max Records Ltd.

0 comments