After a delightful breakfast, Evelyn had to rush off to work. As we parted, she urged me to spend some time visiting the Minneapolis Institute of Art on Third Avenue. I’d been to most of the large art galleries in Europe during the 15 months I toured there, and also the Art Institute of Chicago (which is as good as any of them). Art has always interested me, so she didn’t have to suggest it twice.

But now I was in a bit of a dilemma. I’d promised Melody to be back in South Dakota the next day to visit the Bhagwan for his last session of the year. Perhaps if I left early enough the next morning, I could see the Art Institute today and hear the Bhagwan’s talk late the next day.

Evelyn said the facility didn’t open till 10, so I rode north a few miles along the Mississippi River. As we’d seen heading south the day before, there were lots of green spaces between the road and the river, very scenic. The river itself was flush with boats, both pleasure craft and commercial shipping. I stopped at overlooks several times to enjoy the scene. Couldn’t help but think of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn’s adventures, and Mark Twain learning to negotiate the shallow banks.

I got to the Art Institute assuming I’d visit for a couple of hours, but ended up staying all afternoon. A professor was giving lessons as he toured his class around the facility so I just tagged behind and listened in. It was a fascinating afternoon. There were paintings by such luminaries as Rembrandt, Reynolds, Murillo, El Greco, Manet, Van Gogh, Pissarro, and Gauguin. For pure enjoyment, this place rivaled the one in Chicago.

Chip’s garage was full of after-work renegades by the time I got back to his place. They greeted me with a beer and smiles. Candy approached and asked how I had gotten along with Evelyn. She had that concerned look in her eye, like a mother questioning her kid about his first day in school.

“You look distressed, Candy, what do you expect me to say?”

“Well, it’s not that she isn’t a sweet girl; it’s just that, well, I was worried how you’d react the to the fact that she’s quite Catholic.”

I smiled. “I think she’s quite spiritual, and finds expression of her spirituality through the Catholic Church.”

“I’m not sure how anyone can find spirituality in all those rituals.” KP piped up.

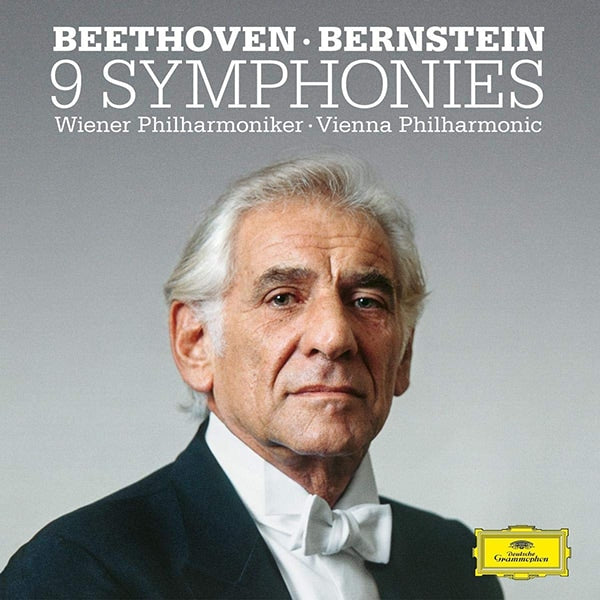

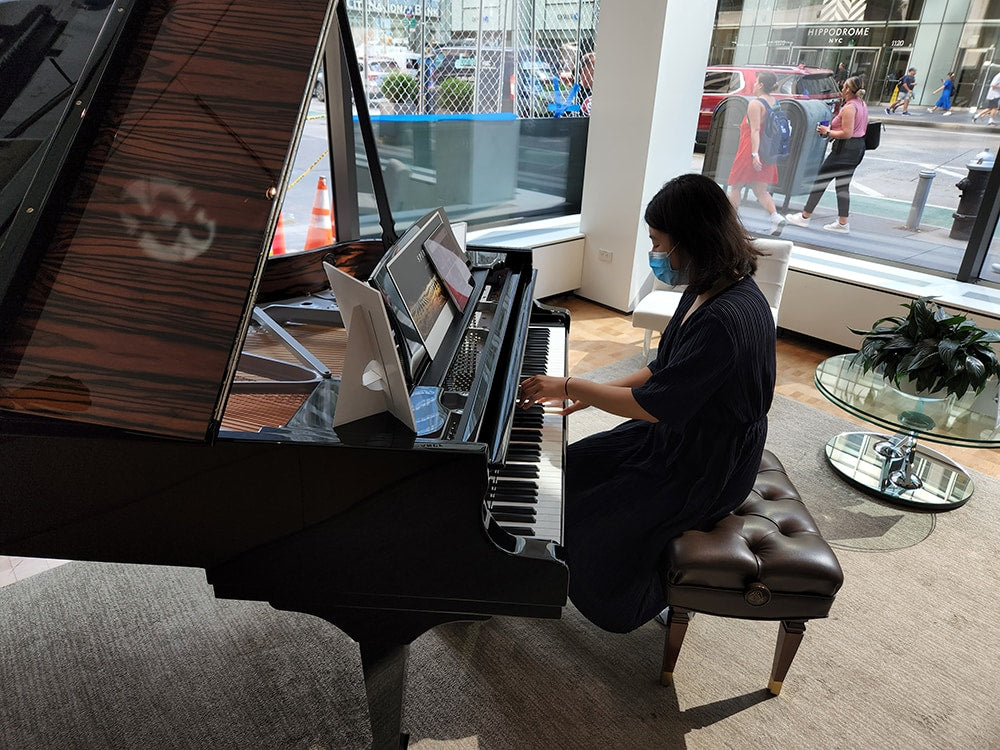

“It’s not the rituals that enrapture her, KP, it’s the music. I share that with her.” I responded.

“Church music!” he exclaimed.

“Musicians have to make a living from wherever the money is, KP. Today, the money is in popular music and movie scores. Back then, the church and the nobility had all the money, so that’s where the best musicians went, like Handel and Bach.”

“That music sounds very boring to me. I prefer Pink Floyd or the Eagles.”

“Have you ever heard classical music live, KP?” I asked.

“I heard a guy singing Frank Sinatra tunes in a bar one time. That was pretty boring too.”

“Different strokes for different folks man; I share Evelyn’s love for church music,” I responded. “I’ve heard it live in many of the great cathedrals of Europe and it is truly a mesmerizing experience. Just imagine how it must have been for the peasants of the day. They live in shacks with dirt floors, work in the dirt from sun-up to sunset, and spend Sundays in these grand cathedrals listening to some of the finest music ever written. That must have seemed like heaven on earth to them.”

“When did you fall in love with classical music?” Candy asked.

“When I was a little kid. I remember listening to it on the radio while sitting on my mother’s lap. At age six, the neighbor girl talked me into going to her Catholic Church. It had a huge organ and a great choir. I was immediately hooked on choral music and have been listening to it ever since.”

“Well, there’s a side of you we never knew,” Chip commented.

“There’s a lot of sides to me, Chip, just like everyone else. I’ve also enjoyed reading too, and spent many evenings discussing books I’d read with my mother after my father went to bed.”

“You didn’t discuss it with your father?”

“My mother and father were diametrical opposites. She came from a family of CEOs, professionals, and scholars. He came from a family of tradesmen. She was an educated thinker; he was a technician. He didn’t know Nietzsche from Buddha, and she didn’t know a nut from a bolt.

“So why did she marry him?” Tina asked.

“He was extraordinarily good looking; he had the face and physique of a Greek statue. He was always the best-looking guy at family gatherings, and she was very proud of that.”

“When I came along, I think he was hoping for a chip off the old block, but unlike the kids who came later, I preferred biographies to bandsaws.”

“That couldn’t have made you popular with him.”

“He could never bring himself to warm up to me, Chip, so he focused his attention on my three siblings. If there was any conflict between us, he always blamed me first. He never laughed at my jokes even if the rest of the family did, didn’t spend any private time with me, and never gave me credit for anything – even those things on which I’d worked hard to please him. Nothing I did was ever good enough. When I told him I wanted to go to college, he wished me luck and walked off.”

“That must have been tough,” Chip probed.

“By the age of 17, I’d had enough. The week I finished high school, I moved to another town to work in a rubber factory in order to make enough money to start college. During my first semester, I learned about the student loan program and that’s what financed the rest of my education. Before I graduated, my father died from heart disease. I never got the chance to confront him as an adult. I was the only person at the funeral not to shed a tear.”

“So why did he have it out for you and not the other kids?” Chip asked.

“When I visited my uncle in Europe, he told me my parents got married by proxy before my father returned from his overseas engagement. When I got home, I asked my mother about it. She told me they were so in love, they just couldn’t wait till he got out of the army. I accepted that because I trusted her. That was dumb!”

“Oh, oh, I have a feeling about what’s coming.” Candy said.

“I didn’t figure it out till I saw a photo of us four kids as adults standing next to each other. All three of my younger siblings resemble each other more than me, all are taller than me, they are lanky and I am not, and all have much more hair.”

“Hell, you must be a bastard!” KP blurted out as everyone burst out laughing. Fortunately, that broke the tension.

“Exactly KP, but I’m not angry at my father anymore. He fulfilled what he felt was his duty, though not happily. I’m mad at my mother for not telling me this when I was a kid. If she had, I’d have understood his behavior instead of spending my youth wondering what the hell was wrong with me.”

“That’s just tragic. I feel terrible for you,” Candy sympathized.

“It is what it is Candy, can’t change anything now.”

“Did you ever approach your mother about it?”

“She became a very religious person in the latter half of her life, so she would have been profoundly embarrassed. I loved her too much for that, so I just let it go. Just before she died, she admitted to my sister that I’d been treated unfairly as a child, but she never elaborated.”

“It probably wouldn’t be a stretch to say that everyone in this garage was treated unfairly as a child, Montana,” Chip asserted, “Maybe that’s what bonds us together.”

As I looked around, I saw the majority nod in agreement, some with tears in their eyes.

“Yah, maybe it is Chip.”

Header image courtesy of Pixabay.com/Peter H.

Previous installments appeared in Issues 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166 and 167.

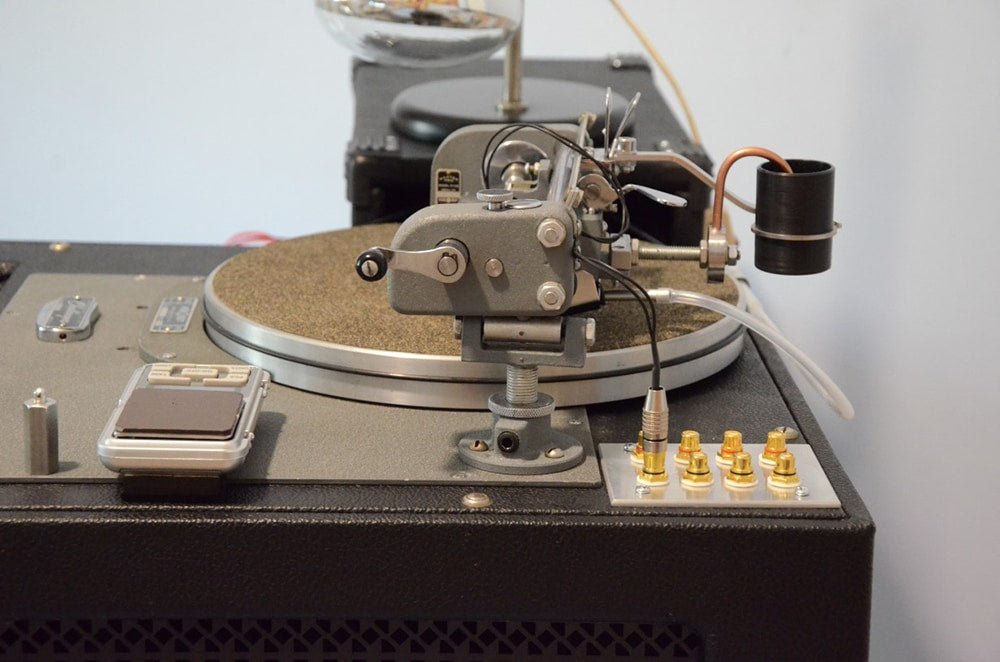

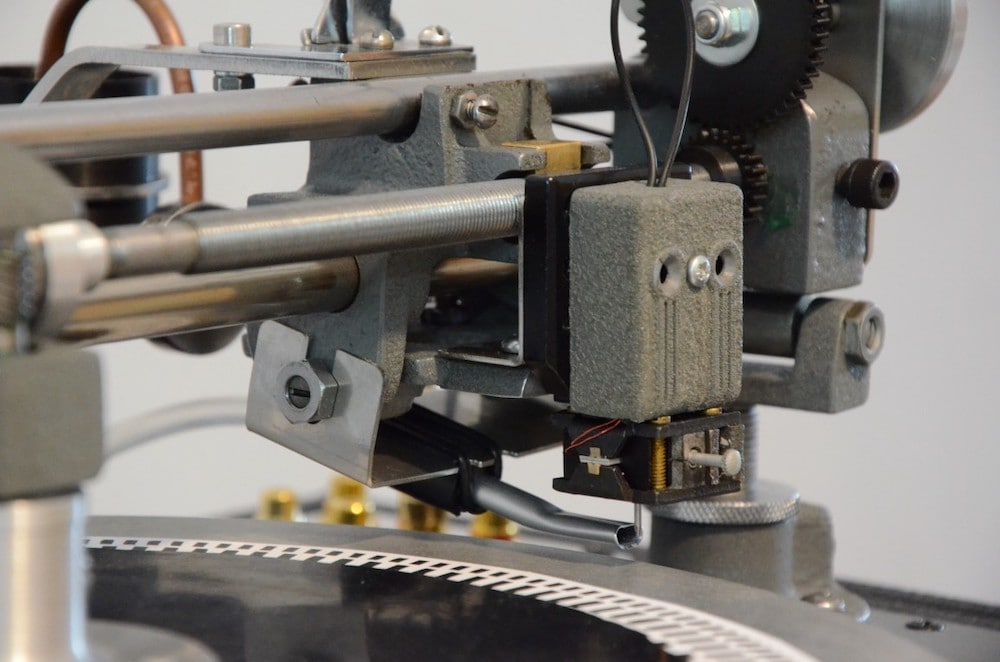

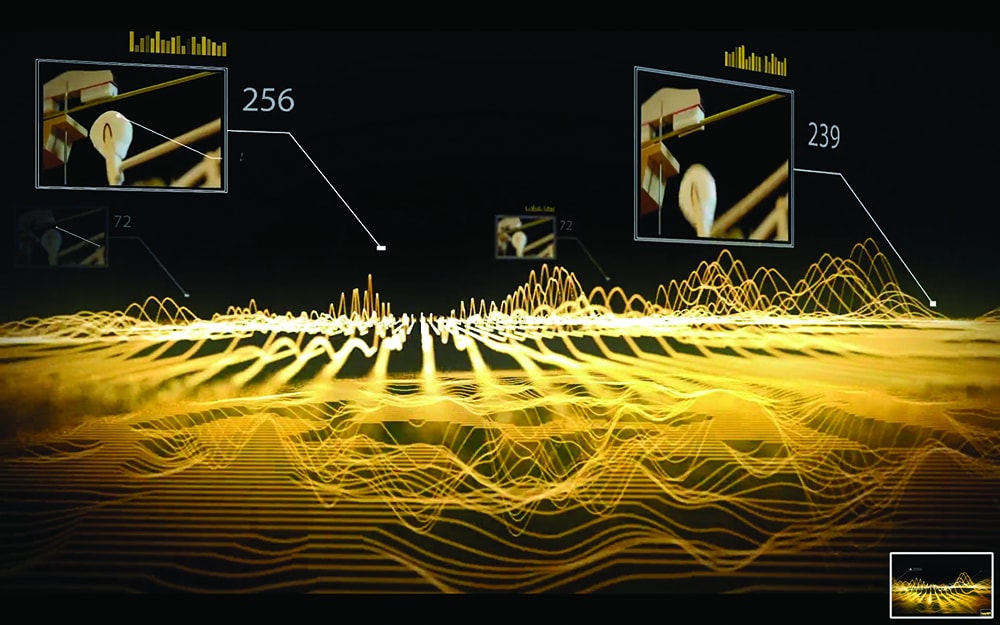

The brainchild of David and Norman Chesky (also the founders of Chesky Records),

The brainchild of David and Norman Chesky (also the founders of Chesky Records),

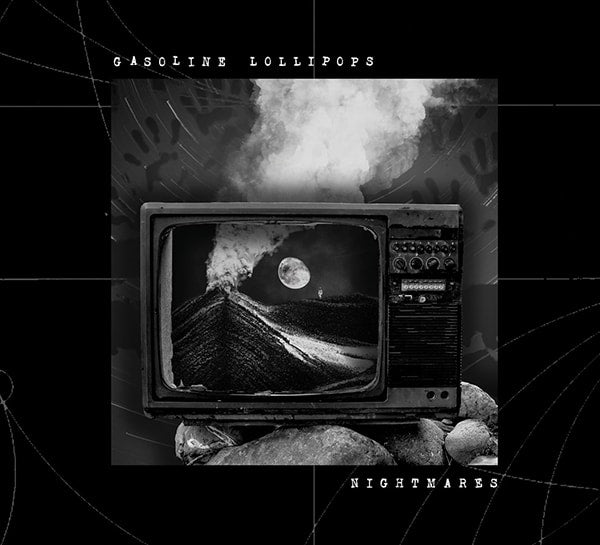

For something a little different, check out

For something a little different, check out