As a direct representative of an era steeped in glitz and glamor, journalist Elise Krentzel’s journey through the entangled jungle of rock music is one of dreams, determination, and perseverance.

From a young age, Krentzel harbored a passion for both music and the written word. Throughout her teenage years as an aspiring poet and writer, Krentzel perfected her craft through self-reflection, and with the help of a few mentors along the way.

After a trip to Europe in the mid-1970s, the wunderkind writer, who was first published at age 17, knew with steadfast resolve that she would one day make it her home, leaving the doldrums of Long Island, a region where Krentzel felt alien, an outcast in the dust.

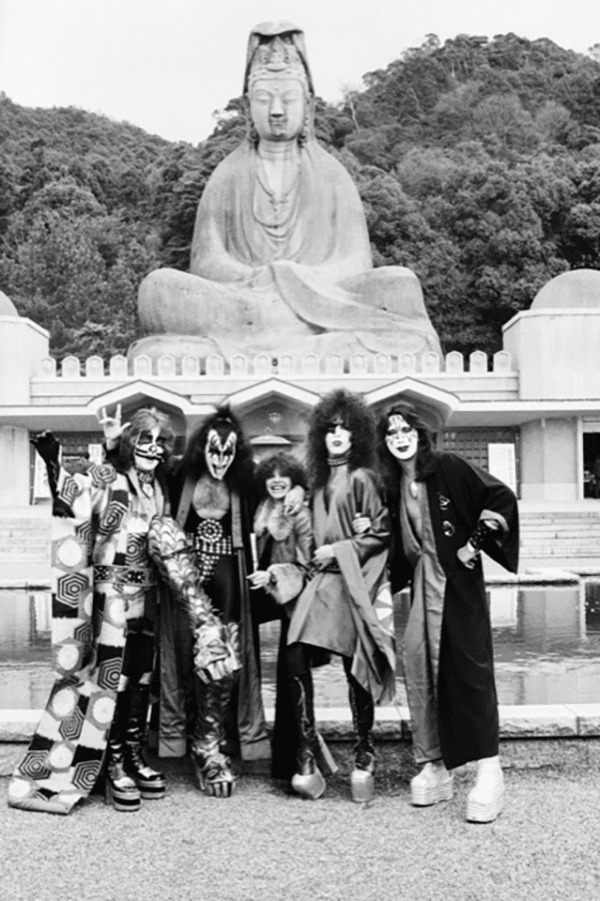

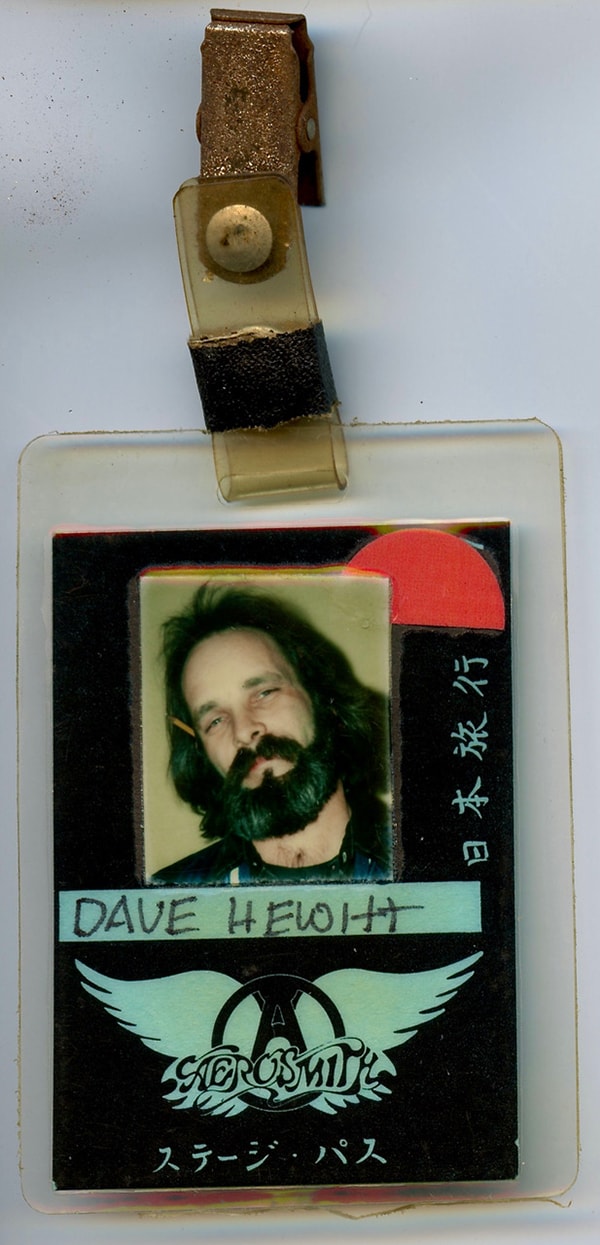

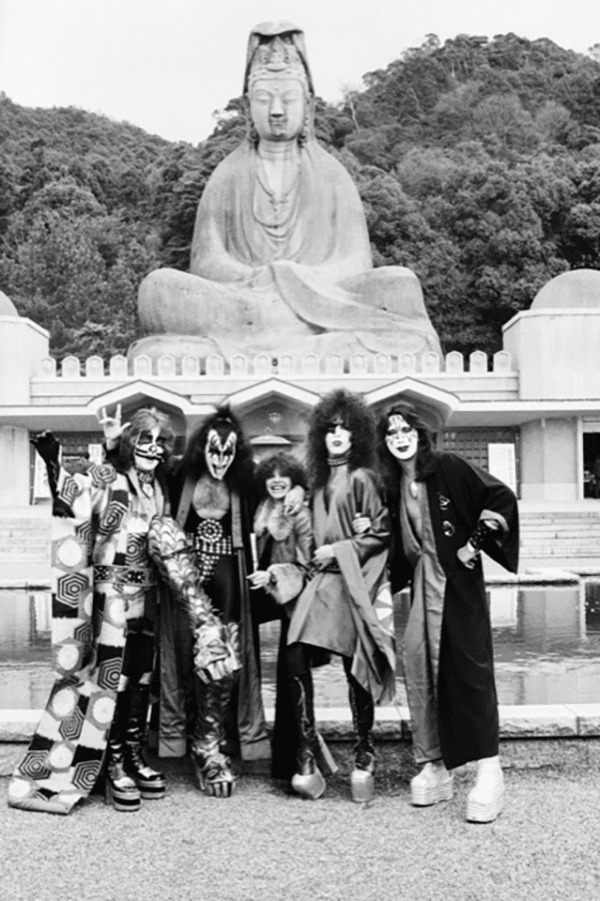

At 19, Krentzel received the call of a lifetime from the press offices of KISS to cover the band on a tour of Japan. Krentzel had not been a part of the “KISS Army” of devoted fans, and set aside trepidations and misgivings she may have had and joined the Kabuki-clad rock warriors on their tour of Japan in 1977.

As one of ten journalists on tour, Krentzel at times faced harsh treatment from her male counterparts, but even at her young age, her professionalism and diligence shined through, and by the tour’s end, Krentzel had parlayed her time with KISS into a full-time gig with Shinko Music, as a talent scout.

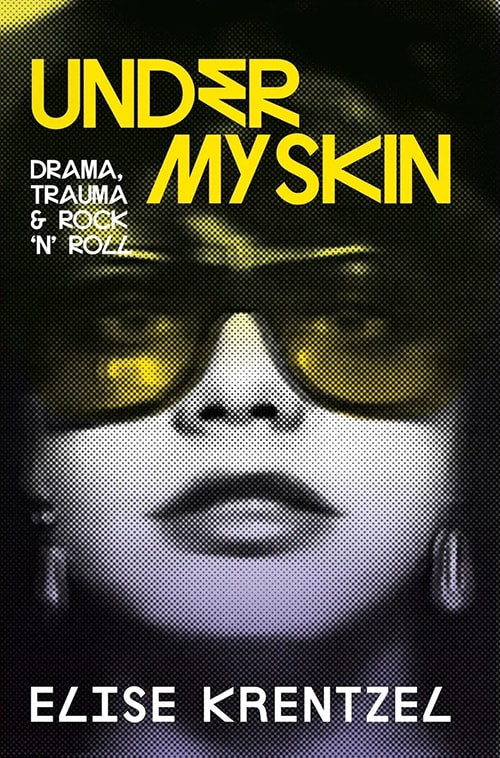

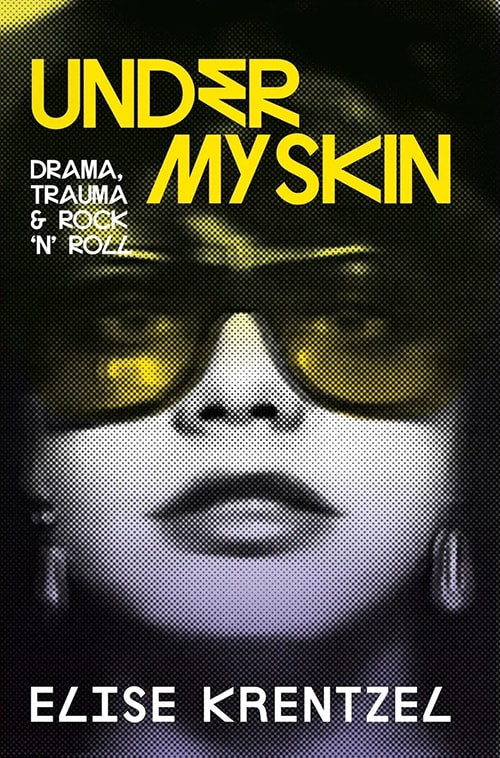

Over the years, as a woman in a male-dominated field, Krentzel has proved to be both a role model and a visionary for young women who came after her. Krentzel’s recent memoir, Under My Skin, subtitled Drama, Trauma and Rock ‘N’ Roll, is part one of what will amount to a three-part series on her life, her trials, her pain, and her triumphs. For my money, as a human being, a KISS fan, and a purveyor of the written word, this is a must-read.

In the midst of promoting Under My Skin, Krentzel took a break from the whirlwind to talk about the people and places that have influenced her journey thus far.

Andrew Daly: What was your first exposure to the arts?

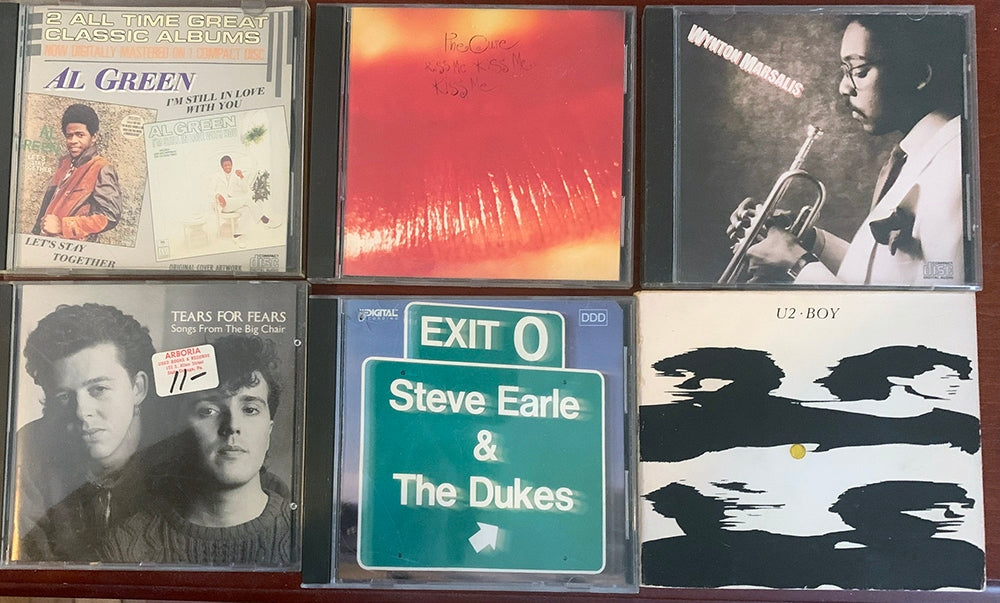

Elise Krentzel: Probably when I was four or earlier. My dad was constantly playing jazz records, and my mom played classical music. My paternal Belarussian grandmother would sing along to “Moscow Nights” and other Russian ballads. I started playing guitar at seven years old.

AD: When did you hone in on both music and journalism? What led you to marry the two?

EK: I was 15, living in a teenage wasteland (Long Island), and had amassed an extensive record collection of around 1,000 LPs by that time. As I wrote poetry and [kept a] journal for years prior, I distinctly remember having an “a-ha” moment and said aloud, “Well, if I love writing and love music, why don’t I become a music journalist?” I didn’t consciously realize how ambitious and driven I was to accomplish my goals, whatever they were. I was at rock concerts at least two weekend nights per month from the age of 14.

Before I was [ever] published, I practiced being a journalist by contributing to my high school newspaper, as well as writing articles for magazines I had no intention of sending to, just for me to practice. I’d come up with album reviews, concert reviews, and faux interviews. Once I had a few that I wasn’t ashamed of showing [to] anyone, I brought them to my mentor – my poetry teacher – and had him look them over. He approved and gave me tips on submitting articles to magazines, [and helped] me write a cover letter. Does anyone even know what that is anymore? (laughs)

AD: How did your early exposure to European culture affect you as you moved forward?

EK: The trip changed my perspective 180 degrees on American politics, culture, and in particular, men. In Europe, I felt at “home” and not like the outcast I was on Long Island. I had male friends, something I craved since my group of friends from middle school was no longer the same group. We all went our separate ways except for one girl who remained my closest friend. The boys were no longer friends. In Europe, I could discuss social progressive politics with anyone who was 16 to 19 years old. They were better-educated than us Americans, more erudite, and informed.

Brit pop was my weakness; fashion from Paris and London and the food culture. And oh my God, I discovered real cheese. (laughs) Not that my grandmothers didn’t expose us to the homemade cottage and farmer cheese (very Russian, very Eastern European), but in Europe, I tried gouda, edam, brie, goat cheese, and emmental. We buttered our bread before laying down meat, jam, and cheese on it in an open-faced style. It was real bread, without sugar and not squishy. I was worried about what I was going to do when I got home as the food was simply awful. One thing I knew after that trip: I would move to Europe upon graduating high school.

AD: Do you feel that it made you a more diverse writer? If so, in what way is that best demonstrated in your work?

EK: I think it made me a more diverse explorer. I liken myself to an archeologist who extracts the gems of a person, situation, or behavioral pattern. The topics I wrote on were about music.

AD: Coming of age in the early days of glam rock, who were some of your favorites, and why?

EK: David Bowie, Mott the Hoople, Lou Reed, The Pretenders, Roxy Music, Nick Lowe, T. Rex, Iggy Pop, (and for punk, the New York Dolls, Iggy Pop, Sex Pistols). Ooh, why? Androgyny. I was androgynous and fascinated with the idea of fluidity. Role-playing? I loved it, and I loved dressing up any which way. As I likened myself to a masculine-thinking female (my approach was considered very male, and men were offended in the business world), I was attracted to feminine-looking men.

AD: The glam scene is credited for more or less launching what we saw in the 1980s. What’s your take on that, and what bands are most responsible?

EK: I can’t say who was responsible for the ’80s, but I can say which bands I gravitated towards. Elvis Costello, Talking Heads, Tears for Fears, Eurythmics, Boy George, The Cure, U2, and Duran Duran.

AD: Journalism is a male-dominated profession, and was especially back then. While it’s improved in the present day, early in your career, there must have been many hurdles.

EK: Ah, that would fill up the page. How much time you got? There were three categories of men. First, the lowlifes who expected sexual favors in exchange for access or information. I’d be hit upon left and right, from A&R men, producers, in the recording studios, managers at the record companies, and others at parties, including male journalists who thought of themselves as better than me. (laughs)

The second were the nasties, and this started on the KISS tour but didn’t end there. Guys in the biz were jealous, intimidated, or both, and wanted to see me fail. They spread lies and rumors and tried to tarnish my reputation. The third type was the elderly statesman, a grandfatherly figure, not in age but in wisdom. These august men took me under their wing and wanted to help me come hell or high water. I always had a mentor, or two, or three to go to when the going got tough.

AD: To that end, would you call yourself a feminist?

EK: To that end, no. I was raised in a non-gender-role-specific household. My father did the dishes, cleaned the house, and did the laundry, and this was back in the 1960s. Mom cooked. I never had to dress a certain way, play with certain toys or define what I liked. If I liked something then I was encouraged to try it. I discovered early on I did not like girlie girls who gossiped, or whose interests were in boys to the exclusion of friendship or other global issues.

In this respect, I found myself on the side of feminism because I wanted equal rights and respect as an individual with different tastes and ways of thinking. I started reading Ms. magazine in 1970 and learned about Betty Friedan and all the trailblazing women who paved the road for me. I read Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying, which resonated 100 percent. I wanted equal rights in my pursuit of sexuality as well, which is why I didn’t wait for boys to invite me on “dates.” Injustice was and still is a huge issue, so to this day, I support causes for human rights. Women’s rights are human rights.

AD: What were the initial conversations that led to you joining KISS on the road in Japan?

EK: It was pretty simple. It was just phone calls from their press office.

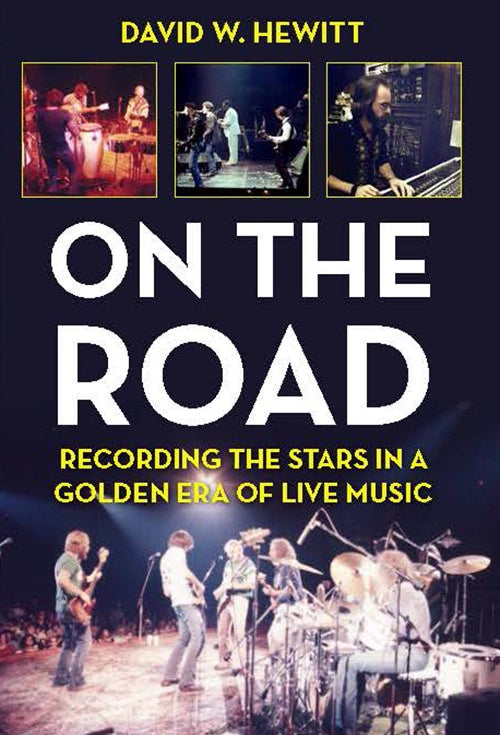

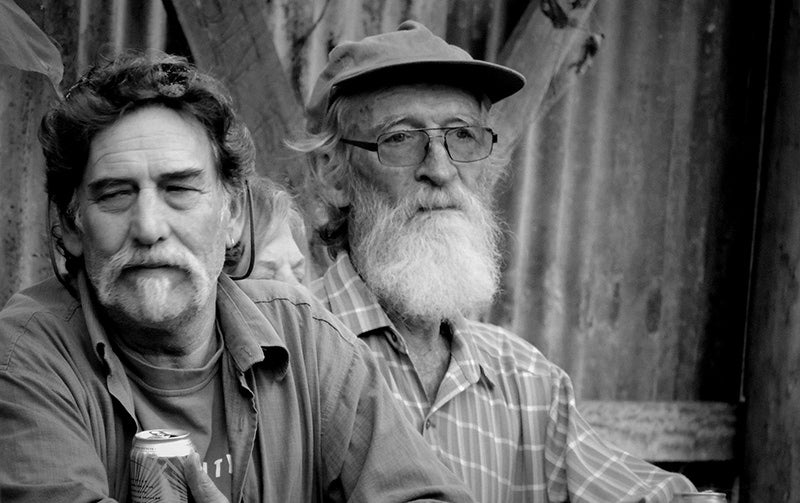

With KISS on tour in Japan, 1970s. Courtesy of Elise Krentzel.

AD: Given some of the band members’ reputations, were you at all hesitant?

EK: Everyone knew of Gene [Simmons’] exploits, and that didn’t bother me because I felt safe and surrounded by his management team, my buddy on tour, Andrew, and a constant entourage of Japanese record company executives. Even when I interviewed Gene, he didn’t faze me at all.

AD: During that trip, what surprised you the most?

EK: Besides KISS’ performances, Japan itself. The country, the people’s mannerisms, the food, the exotic and visually organic environments like rock gardens, temples, food packaging, and Kabuki and Noh performances. The humility and politeness of the Japanese truly appealed to my heart.

AD: Tell us the story where KISS manager Bill Aucoin told you that fateful tour would be the band’s last.

EK: We were at dinner at the Hotel Okura’s French restaurant in Tokyo. He laid it on Andrew and me in a very offhand way. Andrew and I looked at one another and then sort of shrugged, as we had no idea to believe it or what to make of it. Was it a PR stunt? Was the whole Japan trip just a way to gain more worldwide followers? That was my conclusion.

AD: Did Aucoin or the band give you any indication of what their plans were after this “last hurrah?”

ED: Here’s the thing that didn’t make too much sense: after the Japan tour, they were slated to go on tour in Canada. So, what was the last hurrah? A worldwide tour? Is the band splitting? Are members going to produce solo albums after the Japan tour? It’s tough to pinpoint after what, 45 years? But those were the questions running through my mind.

AD: KISS has been famously compared to the Beatles over and over again. I personally don’t see it. What are your thoughts present day vs. your thoughts in 1977?

EK: Good question. Let’s take a trip on the wayback machine. I thought the amount of press coverage, insane emotion the fans displayed, media blasts, and stage phenomena were similar to the Beatles, at least in Japan. Now, I wouldn’t hold a candle to the Beatles because KISS’ music, while iconic, is nowhere near the level of genius as the Beatles, who took pop music to an unprecedented level. KISS fans worldwide are wonderfully devout, almost fanatical about the band, yet compared to Beatles fans, they probably comprise a much smaller percentage, but don’t quote me on the percentages. Pop music is more ubiquitous than hard rock, a sub-genre.

AD: In the wake of the KISS tour, you began working with Shinko Music as a scout. What was your approach to scouting talent?

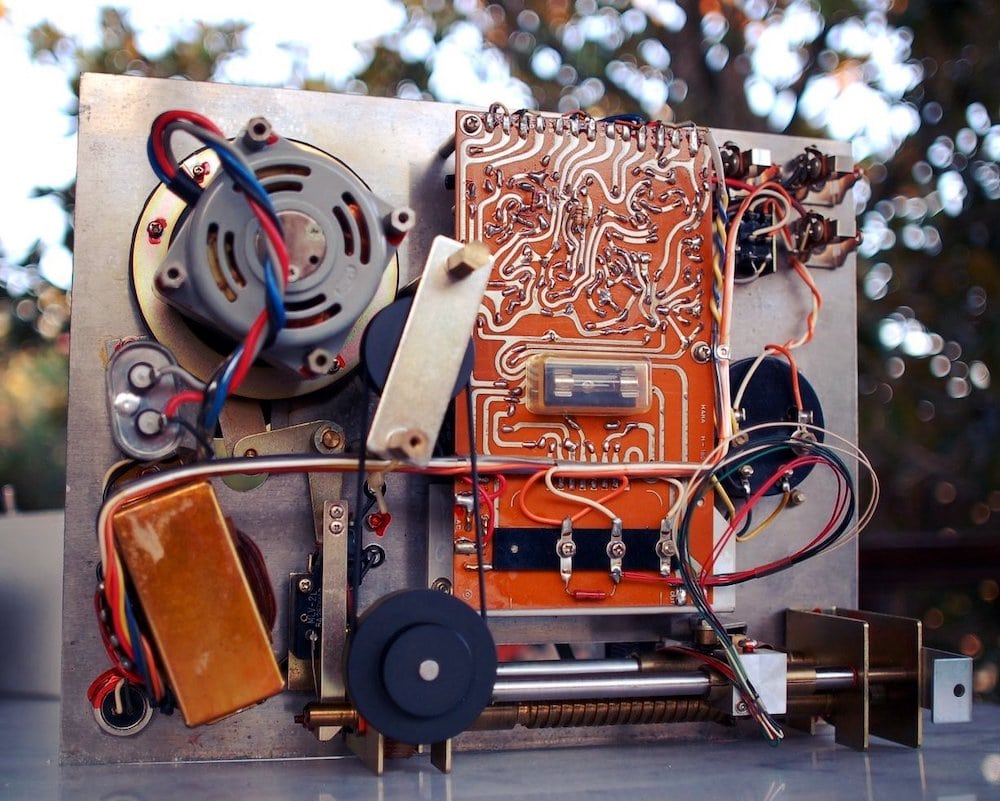

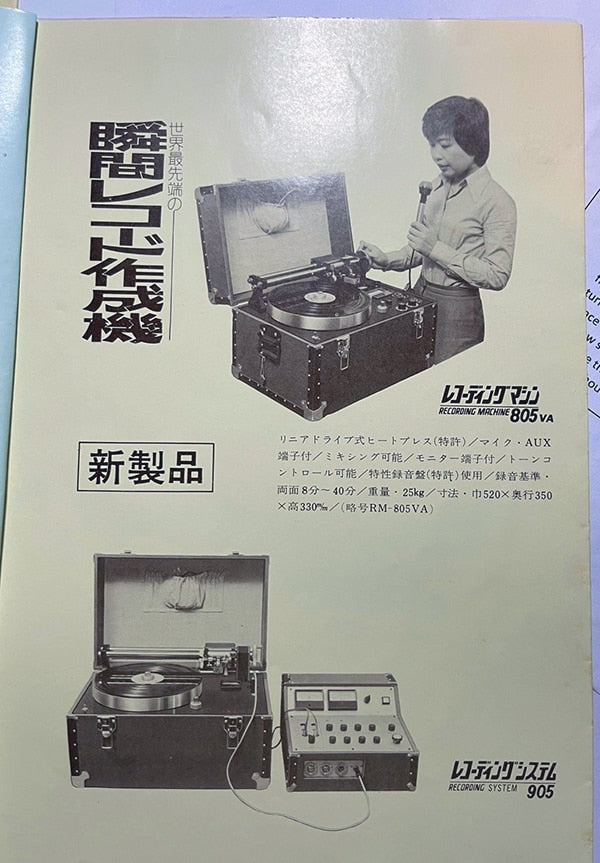

EK: I’d read every music magazine from the UK and US, both consumer and trade. As I was already a journalist, I transferred those credentials while in Japan to earn swag in the form of hundreds of records, LPs and 45rpm, tickets to concerts, etc. Then once I chose bands who I thought had potential, I’d write telexes and postal mail to the band’s publishers, management team, and foreign record companies. Then I’d pitch it to the local Japanese label to build up momentum to get them to promote the albums to the public. Once there was steam, Shinko (and eventually me as I started my sub-publishing and talent agency later), would sign on for the publishing rights in Japan.

AD: Were there any you felt would be sure bets but never made it?

EK: Punk rock became trendy but didn’t make it as big as say, Queen, Aerosmith, Bowie, or other significant acts. Some of the punk rock acts that didn’t make it were Ian Dury and the Blockheads, and Lena Lovich.

AD: What makes now the right time to finally get your book, Under My Skin, out there?

EK: Because finally, I got around to putting pen to paper after decades of therapies and self-help stuff. I wrote two books that were not published. I guess I put my past behind me enough so that it wouldn’t emotionally cloud my humor, or interfere with the painful parts of my life. It was timely since the ’70s are back in vogue. I have a quote, “it takes a long time to be on time.” (laughs)

AD: Has the process been stressful, cathartic, or something more?

EK: One of the main reasons Under My Skin wasn’t written earlier was due to my fear of putting to paper metaphorically all the tragedy, drama, trauma, and hurts of my past. I was knotted up. I couldn’t see how to unfurl my past with humor that was hidden due to fear of exposure. As I wrote each chapter, the flow was natural, and the words just poured out.

AD: This book is only part one, right? How will parts two and three shake out?

EK: Think of it as the three stages in life. Stage one covered the ages of five to 20, and much of the focus was physical, whether physical abuse, sexuality, or school-age peers.

Book two is entitled Men Moving Me, covers the ages of 20 to 44, and will focus on emotional growth, international relationships of treachery, betrayal, alienation, traveling, moving around the world, and giving birth.

Book three is the mental equivalent of maturity and growing into adulthood (I have a Peter Pan complex, so turning 65 in a few weeks makes me giddy as I finally become a senior citizen) as a woman, mother, and friend to myself who learns the true meaning of love.

AD: When you reflect on your career, how do you quantify your influence and accomplishments?

EK: I don’t quantify any longer, I qualify. I qualify it by how many people I’ve helped along the way, through mentorship, or guidance to create better circumstances for themselves. I qualify it by looking at clients who implemented my out-of-the-box suggestions, and those who, while at first resistant, changed their strategies. Accomplishments to me are lifelong and in flux. Once I achieve a goal, there is always another one, so reaching it is not exactly an accomplishment. To me, accomplishment is the process of doing, getting up every day, and not giving up. Every day I focus on the goal, not the outcome.