I was not thinking about much; mostly I was just channel surfing, at home watching television, half paying attention at midnight on a Sunday night. I was in bed but not yet ready to fall asleep. I’m going through the higher channels and I come across Jim Chladek on public-access Channel C.

He is live, with one fixed camera on him, sitting behind a desk in his television studio located nearby at 110 East 23rd Street, a commercial building just one door west of Manhattan Cable’s headquarters. Jim is talking about the ease and the whys and wherefores of having a public-access or a leased-access television show on Manhattan Cable TV. Really? I am more than interested.

It was the mid-1980s and people had fewer distractions. Personal computers were not really a thing yet and cell phones were just a blip on the radar. Cell service was new and ridiculously expensive. At the time I was working for an electronics installer (phone systems, stereos and so on), on the 3 pm to 11 pm shift. My boss, Gary, had recently bought a car/portable cell phone. With the battery and receiver cradle on top, it was the size of a box of cereal, and he carried it everywhere. Calls only, no internet. His first month’s bill was about $3,000. That was the end of that, and he went back to pagers.

Late-night alternative television watching was then a secret activity practiced by thousands of insomniacs. It made sense. New York is the city that never sleeps. Public-access television was getting attention in the US, especially in New York City, due to the advent of cable TV’s spreading footprint in the seventies and eighties. At first it was because the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) required them to offer public-access TV, but then the idea of public access became a way for the monopolistic cable companies to win over local municipalities.

According to HowStuffWorks: “The advent of public access TV occurred in the early 1970s under Section 611 of the Communications Act, a decision that gave local franchising authorities the ability to require cable companies to set aside channels for public, educational or governmental (PEG).”

I was watching Channel C that late night and Jim was talking about the available time slots and how to go about applying for one, and why MCTV (Manhattan Cable) had to approve any programming. He explained that it was required by the city that the cable company had to dedicate two channels for public access, and one channel for leased access. Leased-access could be commercial and have advertising, whereas public-access allowed no advertising. I am pretty certain that this was and still is a requirement for many of America’s cable companies. The reality was that the licensing for the cable franchises had to be approved by a city’s councils. They considered public-access a platform for free speech. (Cable companies had control over what channels would be aired.) To sum it up, it seems the thinking was that the public should have the ability to make its own programming without editorial (i.e., commercial network) restrictions, and no enforcement unless there was a complaint and even then, maybe. Enforcement was little to none to say the least. Personally, I do not think MCTV or the later MNN actually watched these shows, so unless there was a complaint we did whatever we wanted to.

Cable companies spend a ton of money to create their infrastructure. The cost to lay the cable, mostly underground, and then to send the wired signal to each apartment building and to the homes of subscribers is substantial. These franchises do come up for renewal, but really, municipalities had no choice but to renew. Though I am aware of some changes of ownership, I don’t know of any cases of any cable company’s licenses not being renewed.

If you consider the initial cost to build a cable TV system, expand it, and maintain it, then there had to be some kind of protection for the cable companies. Also, the revenue in tax dollars from these companies is significant for government. Having said that, a surprising amount of the cable company’s expenses and certain construction costs become the financial burden of the subscribers. There really was not much more the cities could ask for from the cable TV companies. New York City Council did ask for better customer service, which was a big issue, though it has improved over the years. However, public access was one request that local governments could all agree on. It was not much of a burden on the cable franchises, and the reality of it is that the cost is passed on to the cable subscribers. Look for the PEG fee on your cable bill. Mine is $2.30 per month. The New York City government loves to tout its support for freedom of speech and its position that the cable companies do not have a death grip on all of their content.

It was a given that practically any adult resident could get a time slot for their taped show, or even a live show from select studios. The producer agreed to supply 26 weekly programs of 28, and in a few cases, 58 minutes. There were general requirements – the shows could not contain advertising or violate hard-core pornography standards. The technical rules were that the videotapes had to be in 3/4-inch U-matic cassette or Betamax, and with an opening countdown with two seconds of black prior to the first frame of video. At the time, the smaller local newscasts used the commercial 3/4-inch format, mostly for their B-roll videos. (B-roll is supplemental footage that is intercut with the main footage or broadcast.) It provided a higher resolution than VHS and Beta consumer tapes. With all that taken care of and a contract signed, the producer was sent off to create.

Sony U-matic SP video tape recorder. Courtesy of Wikipedia/DRs Kulturarvsprojekt.

A couple of things to keep in mind were that if you did not regularly submit shows, you could lose your time slot. Also, you did not own your time slot, and after a six-month period MCTV (and from 1992, MCTV created the Manhattan Neighborhood Network, MNN) could move you to a different slot to accommodate a new show. The use of reruns was discouraged.

I was intrigued enough to apply for a public access show. Shortly after, I had a time slot for my show. The process was easy. I went to MCTV, filled out a couple of forms, showed ID, and a few days later I was approved. The Cable Doctor Show ran on both MCTV and Paragon Cable, covering all of the Manhattan. That was over one million potential viewers. My first time slot was on Channel D (17) at 11:30 pm on Thursdays. It might surprise readers that this was an excellent time slot. It goes against the common assumption that prime time would be the best, but that is not so. Public-access programming cannot compete with prime time network shows. The sweet spot for public-access audiences is 11:00 pm to 2:00 am, and sometimes even later, up until early morning. To a lesser extent, afternoons up until 5:00 pm are also good.

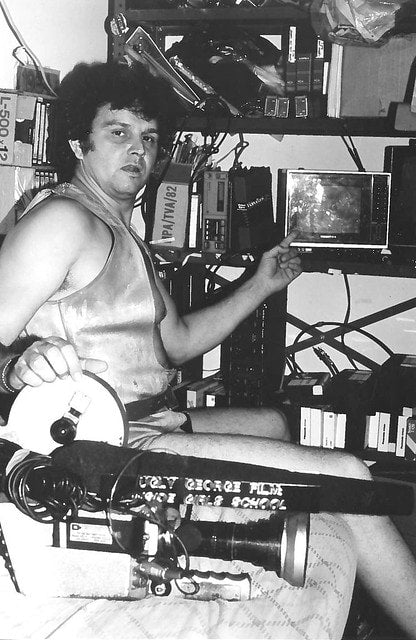

The programming in those early days was varied to say the least. There were quite a number of outrageous shows, including soft-core porn for late-night. Early on Manhattan viewers could watch Ugly George, who would lug a heavy video camera around and somehow convince women to disrobe and conduct interviews on camera. Midnight Blue was hosted by Al Goldstein, the owner of Screw magazine. He had a 58-minute show on leased-access. He was outspoken and gave a lot of on-air editorials. Midnight Blue also included some visual content. It was all sex-related. Leased-access is not free; at thei time it cost $100 for a half-hour. Because it is leased-access, the shows can be commercial (for-profit). Like public-access, a certain amount of leased-access airtime is mandated by the FCC.

Ugly George in post-production at his midtown loft for his public-access show The Ugly George Hour of Truth, Sex and Violence. From the 1988 documentary Rate It X by POV Docs.

The Robin Byrd Show on public-access and leased-access featured strippers who were performing at local clubs. The strip clubs sponsored Robin’s show in order to increase their attendance. Think Stormy Daniels on tour, though this was way before her time. By today’s ratings these shows would be seriously R-rated. The Robin Byrd Show is still on the air today, on Manhattan’s Spectrum Cable.

Public-access was a great platform and a terrific way to promote an idea. Psychics had call-in shows. A dentist had a show. Behind the Velvet Rope featured fashion and runway events and interviews with designers. Another show featured songwriter John Wallowitch, who appeared on the air live, seated behind the studio’s slightly out-of-tune piano with a money-stuffed brandy snifter and a brass-framed picture of his mother, and took viewer requests. He used to say, “this is the only piano bar of the airwaves,” and he found himself playing ”Fly Me to the Moon” quite a bit. Sometimes he was on after my show. He told me he had a permanent gig at a piano bar on First Avenue in the lower Fifties. Production on these shows was varied, but certainly not of network quality.

These were also exciting times in the field of home electronics technology. The VCR started to really take hold in the 1980s, giving a previously-unheard-of ability to record off your cable box. Sony’s Betamax format had slightly better video quality than JVC’s VHS (for Video Home System), but the recording time on Beta was more limited, so eventually Sony bowed out of that battle. The U-matic professional video recording system was the precursor to these consumer recording formats, though earlier video recorders existed as far back as 1963.

It occurred to me to use my public-access TV show to explain new consumer tech to people. My hope was to eventually establish an installation and service business. One thing that spurred the idea was that the VCR had become a big seller. However, the number one complaint I heard from folks was the annoying blinking of a VCR’s clock at 12:00. Most people could not set the clock, and thusly could not program the devices to record. The blinking light was driving people – Luddites – crazy. Hence, my inspiration for The Cable Doctor Show. This was my first of three different cable TV shows I created, and I had close to a dozen time slots over the years.

The Cable Doctor Show was a live broadcast with call-in tech questions, like an AM radio call-in talk shows, but focused on technology. In order to broadcast live, the show had to be telecast out of Jim Chladek’s studio at a cost of $100. That money bought me a live two-camera shoot in the studio, and the use of the control room with a call-in line. The number was posted on the screen along with a chroma key composited background. If you wanted a copy of the show, you could buy a blank U-matic tape for $10 and the studio would record the show for you. The tape could be used for reruns or just as a permanent record.

Things were really starting to happen in the consumer video world. S-Video came out, and now you could videotape-record at up to 400 lines of resolution. Standard VHS was only 320, so this was an improvement. Portable video cameras were starting to become in vogue, though they were big, the size of the cameras the networks used. The resolution was just standard video, only good enough for home recording.

At first The Cable Doctor Show was live call-in with questions. There never was a shortage of calls. After a couple of months, I decided to break up the 29-minute show by segments. I would start the show with calls, then do a setup or installation demo. For instance, a segment on how to install an A/B switch box and why a viewer would want one.

We were off to a good start, and just in a couple of months I was getting recognition.

You never know what is going to happen next. You try your best and you gotta believe. The unknown is not necessarily a terrible thing.

0 comments