“All right, that’s enough of that,” Chip proclaimed. “Let’s mount up.”

I looked at Candy. “It’s 7:30, where are we going?”

“Oh, every Thursday evening, all the Harley guys ride into town and hang around Main Street till dark,” she replied. “We’ve been doing it for years.”

“What’s the point?” I asked.

“I think it’s mostly a social thing, talking, kicking tires, admiring each other’s machines, and so on.”

“It’s also about keeping the peace,” Chip interjected. “We’ve had some turf wars between the clubs and this is their way of resolving issues before they flare up. The reason our group doesn’t wear any club colors is because we just don’t need the hassles that come from inter-club rivalries. We’re just here to have fun. I think the other clubs respect that.”

“Will there be any non-Harleys there?”

“Oh yah, there’s always a smattering of Japanese and European bikes.” Chip assured me, “You’ll fit in.”

“All right then, let’s go.”

We all rode downtown as a group including KP with his oversized, bandaged finger.

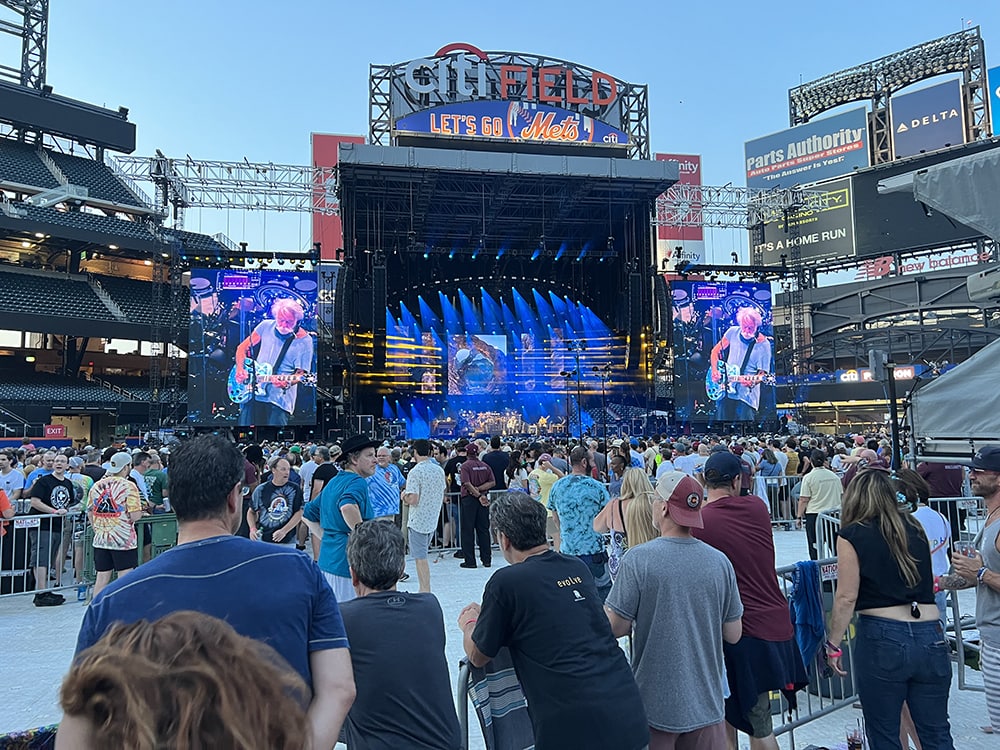

As we rounded a corner, I saw hundreds of bikes lining both sides of the street. It reminded me of a mini-Sturgis rally. We filtered in wherever we could find a place to park. I ended up taking a spot that a clubber had just vacated, in between a bunch of other clubbers. I felt conspicuous as they watched me park. After I shut my engine down, I asked, “OK if I park here? Is your buddy coming back?”

“No man, you’re good; if he comes back, he’ll have to find another place,” the group agreed. These guys were all wearing Hell’s Angels (HA) colors and I found them as intimidating as the renegades when I first met them.

“Well, I don’t want to piss off the Hell’s Angels; I’ve watched all your movies, you know.”

Several of them broke out laughing. “They’re not our movies, man. Every time some producer wants to make a cheap movie to freak out the citizens, he hires a bunch of B-grade actors to make us look bad.”

“Yah, they treat us like sharks,” another clubber added. “Everybody is terrified of them, but the fact is that they kill only a few people per year. Yet Hollywood makes fortunes off shark movies. Deer on the other hand, are responsible for 20 times as many deaths, but you’ll never see a movie called Antlers!”

Everyone broke out laughing.

One guy said, “I can see the movie poster now, a photo of a dark, wooded area behind a two-lane, blacktop road. If you look closely, you can see the antlers of a full-grown Bambi with a homicidal look on its face. Above is the caption, ‘If You Survive Tonight, We’ll Get You Later’.”

“That’s sure to traumatize every family in our National Parks.” I added, “Their kids will have nightmares and run screaming to their parents every time they see a killer deer.”

There was more laughter. “We’ll, that’s pretty much how I’m treated in public.”

“When you’re wearing your colors?” I asked.

“Right, we can’t really wear our colors most of the time because Hollywood has associated them with danger. Most of us aren’t any more dangerous than the mall cop.”

“But I’ve seen a few bad stories about Hell’s Angels in the news,” I said.

“Yup, there’s been a few bad actors in Congress and the Stock Exchange too, and they do a lot more damage than any biker. Nobody can control all the bad actors.”

“That’s a good point,” I agreed. “I’m Montana. What’s your name?”

“They call me Joker, Montana. How ’bout I buy you a beer?”

Joker and I walked into the bar located behind their motorcycles and the whole club followed us in. He asked me a lot of questions about my bike, and thought the color was outstanding. He was incredulous when I told him I’d put 75,000 miles on it with nothing but routine maintenance.

“Ever heard of a rally called Sturgis, Montana?”

“Yah, I just spent a week there. That’s why I’m in Minneapolis. I met a bunch of guys who invited me to come visit, and I’ve really been enjoying it.”

“Harley riders?”

“Right; there’s not a lot of BMW riders to meet in Sturgis.” Everybody laughed.

“Who’d you meet?”

“Chip, Candy, KP, Spider, Gimp, Tina.”

“I know those guys. I heard Red killed himself.”

“Yah, he took out a couple on a Gold Wing too.”

“You know that crazy bastard almost started a gang war?”

“Hadn’t heard that,” I responded.

“Yah, when a Bandido chapter formed in town, Red tried to become a member. But they weren’t interested in a burned-out doper like him, so they told him to hit the road. ‘Fine, he said, I’ll join the Hell’s Angels.’

The next thing I know, some Bandidos are accosting me on this very street accusing me of stealing members. I’d never heard of Red, so I asked where I could find him. They pointed to a bar across the street.

Red was sitting with Chip and those guys but I didn’t know that, so I walked in and asked who the hell Red was. Red started to get up but Chip pushed him back down and told him to shut the hell up. Chip came up to me, I told him the story, and he told me that the Bandidos had rejected Red, and that the Hell’s Angels likely would too.

So, I asked, ‘Why’s he sitting with you guys then?’ Chip answered with one of the funniest lines I’ve ever heard, ‘Well,’ he said, ‘we’re a club for rejects.’

I busted out laughing, I couldn’t help myself. I put my hand on his shoulder and told him he was performing a valuable service. I went back across the street and told the Bandidos and we all had a chuckle over it.

I’ve since become friends with Chip and often see him at Jake’s Tire Shop. He’s a sharp guy. Well, speak of the Devil!”

Just then Chip walked in. “Hey Joker, just checking to make sure Montana’s not giving you any trouble.”

I responded, “The only trouble I’m having is that these guys won’t let me buy a round.”

Joker responded, “Don’t worry ‘bout that, Montana. Your crew dropping by tonight Chip?”

“Oh yah, all right if Montana joins us?”

“Sure, all you Rejects are welcome,” he laughed.

“Great, see you about 10. Why don’t you come with me, Montana?” Chip asked.

“Let me give you some money, Joker.” I reiterated.

“Get outta here,” he barked.

“Not sure why I can’t buy a round,” I told Chip as we walked across the street; “Maybe it’s some kind of an honor thing.”

“The HA haven’t paid for anything in that bar for years and the owner wants it that way.”

“I don’t get it.”

“About five years ago, this place was claimed by the Pagans motorcycle club. The Outlaws MC didn’t respect that, so they walked in one bike night and a huge battle ensued in which some clubbers were hurt and the place was trashed. It was weeks before they opened up again. So the owner approached the biggest, baddest club he knew of, the HA, and asked them to make it their home turf during bike night in return for free booze and pizza. There’s been no battles in there since.”

“Good Lord, I never knew such things happened. So are you going over to Joker’s place after this?”

“Yah, you’re coming.”

“I don’t think so, Chip.”

“Trust me, you’ll love it, we leave in half an hour.” Chip had a way of expressing a plan which didn’t leave much room for free choice.

It’s one thing to have a beer with a clubber in a public place, I thought, but it’s another to have it on his home turf. I didn’t feel comfortable about it but I trusted Chip.

We rode to the northeast part of town through an attractive neighborhood and came to a riverside park facing the Mississippi. We stopped at a giant, brick house with a wide porch out front. It was situated on what seemed to be an acre-sized lot and faced the park and the river. There was a circular driveway out front guarded by a gate. As soon as Chip punched in the code, the whole area lit up like a tennis court. We rode in and parked amongst the Harleys already there. We could hear the music as soon as we shut off our motors.

In front of the double entry doors, a couple of guys looked us over and said, “Hey, Chip, everybody here with you?”

Chip reviewed us as if he was checking. “Yup, they’re all my crew.” With that, they waved us in.

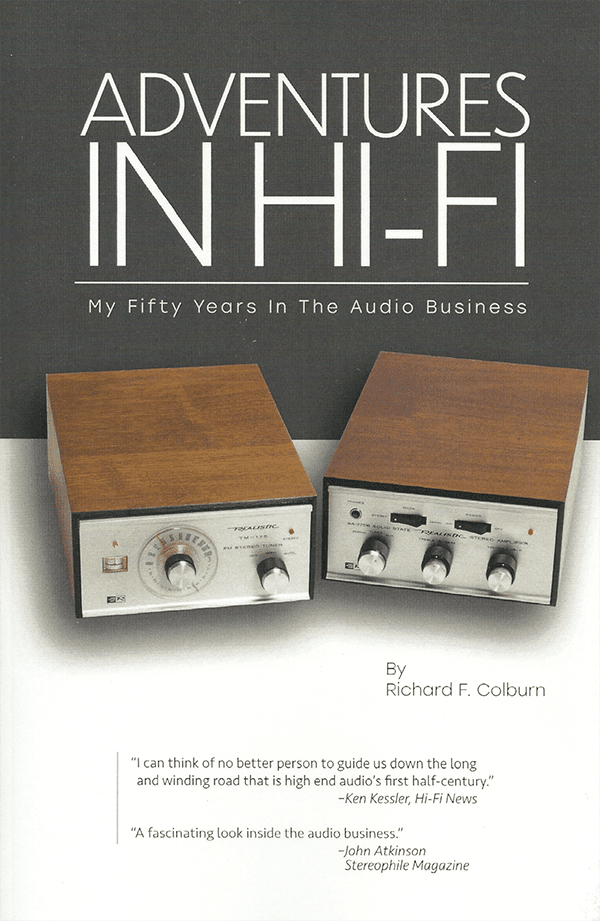

The heavy, oak doors opened up to a Great Hall with a facing staircase at the far end. The walls were covered in wood parquetry that matched the floors and the balustrade on the stairs. I felt like I was walking into the set of Gone with the Wind. On either side of the balustrade, I recognized the four towers of an Infinity IRS V speaker system! It sounded wonderful in this space.

The Victorian furnishings were equally grand, but covered in people wearing leathers, boots, and patches, and carrying beers. What a contrast. I thought of the kind of parties the Rolling Stones must have thrown in Jagger’s castle.

A classy lady greeted us and led us to the kitchen. The kegerator had eight taps, all marked with different brews. The dining room table next to it was half-covered with appetizers and half-covered with steaming, stainless steel buffet servers.

The lady was wearing tight, glove leather pants and a loose white blouse. I smiled at her. She extended her hand.

“Hi, I’m Leanna, what’s your name?”

’Nice to meet you Leanna, I’m Montana and I came with Chip.”

“I can see that. Are you from Montana?”

“No, I’m from Southern California, but that doesn’t quite have the same ring to it.”

She chuckled. “So why Montana?”

“Cause when I met the renegades, um, Rejects, in Wyoming, they all introduced themselves with nicknames, so I had to think quick. As I’d just rode through Montana, that’s what I blurted out.”

“That’s hilarious. How do you like this house?”

“It’s spectacular, I’m blown away. Even the furniture is perfectly matched.”

“Neither Joker nor I knew much about furniture, so when this place became available with the furniture included, we jumped at it.”

“Ah, you’re the lady of the house?”

“Right, for now anyways.”

I really didn’t want to know any more, so I asked her for the location of the rest room and made a polite exit.

On the way over, I was intercepted by Joker. “Looks like you met Leanna,” he said.

“I did,” I responded..

“Why don’t you join me later?” he asked. I nodded, but didn’t want to get involved in any domestic issues.

I got another beer and headed back to the great room. Joker was sitting next to Chip, who waved me over. “Oh, oh!”

“Chip tells me you used to work in probation?” Joker asked. “So did I.”

I was surprised. Joker and I swapped stories about probationers, the court system, and the revolving doors of justice. We shared lots of laughs and beers for an hour or two. Then Chip came over and told me it was time to leave.

“I have no idea how to get back to Chip’s place from here, Joker, so I’ve got to follow him.”

“You can party some more and spend the night here if you want, Montana.”

“I’m honored, Joker, and any other time I’d love that, but all my stuff is at Chip’s. I’ve got to pack tonight in order to get an early start. But it was a real pleasure to share stories with you.”

“See you in Sturgis next year, Montana.”

‘I’d like that, Joker, and thanks for the gracious hospitality.” He nodded and smiled.

The ride home seemed to take an hour, and I plopped into bed immediately upon arrival.

I packed up as early as possible the next morning and hit the road at the crack of noon.

Editor’s Note: we are aware that “gimp” can have a derogatory meaning and mean no insult to anyone disabled. In the story, the person with that nickname doesn’t consider it as such, and we present the story in that context.

Header image of the Mississippi River courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Tony Webster.

Previous installments appeared in Issues 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167 and 168.