The Musical Instrument Museum (MIM), located in Phoenix, Arizona, is the foremost musical instrument museum in the world with 350 exhibits, 200 of which are country-specific. I described it in a previous Copper article (Issue 168), and in this and following installments I’ll note some of its particulars in greater depth.

Five of the MIM’s ten main galleries are geography-oriented for the following regions:

- US/Canada

- Europe

- Africa/Middle East

- Asia/Oceania

- Latin America

For the last five years, I have been a volunteer giving tours to adults and school groups at the museum. In addition to participating in MIM’s museum guide training and certification process, docents get to attend regular enrichment sessions hosted by the museum’s curators. There are also opportunities to gain important musical insights via one-on-one discussions with those curators. Additionally, I have done extensive research into various aspects of music, much of which has been fueled by my involvement at the museum.

I would like to now take you into MIM’s geographic galleries and discuss some of my favorite exhibits. Let’s take a trip around the world!

The US and Canada: Early Jazz

Few people dispute that jazz was invented in New Orleans around the turn of the 20th century. Why New Orleans and not New York, Chicago, or some other city? There was a dynamic confluence of cultures in New Orleans at that time. These early jazz artists were primarily descendants of Africans, or Creoles. Creoles in New Orleans are a predominantly mixed-race culture rooted in French, Spanish, African or Native American ancestry among others. I would like to profile an African slave descendant and a Creole and discuss their contributions to the origination of the jazz genre of music.

Buddy Bolden, born in 1877, was the son of former African slaves and many experts view him as the father of jazz. Buddy played the cornet and by the mid-1890s had his own band. Whenever there was a parade in New Orleans (and there were many), Buddy’s band would steal the show. They were highly creative, played loudly, and were known for their innovative improvisational techniques. Buddy had a magnetic personality and a profound impact on other musicians. He developed a cult-like following and always had an entourage around him. On Saturday nights, you could hear his band from great distances but actually getting to see them was a very tall order due to their popularity. Buddy was given the nickname “King Bolden” in New Orleans.

Buddy Bolden and his band. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/public domain.

So why have most people never heard of him? For starters, he was never recorded, didn’t document the songs he created, and there is only one known photograph of him. But the main reason is undoubtedly that at the age of 29 he suffered a psychiatric breakdown (diagnosed as schizophrenia) and spent the last 24 years of his life in a psychiatric facility. King Bolden is buried in a pauper’s cemetery in New Orleans. A large monument commemorating him has been erected there but they have no idea which headstone is his. The father of jazz!

Jelly Roll Morton, a Creole, was born Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe and was 12 years younger than Bolden. His mother’s maiden name was Monette and after she and her husband separated, she married a man whose last name was Mouton. These are all French names. Ferdinand adopted the Mouton name. As a teenager, Ferdinand was supposed to be working part time as a factory watchman, but what he was really doing was playing piano at some of the brothels in New Orleans. A nice middle-class boy didn’t do such things and he tried (unsuccessfully) to hide this from his family. With that in mind, he changed the “u” in Mouton to an “r” and became Jelly Roll Morton. (I’ll decline to explain the origin of his “Jelly Roll” nickname; you can look it up.)

Morton had a reputation for being egotistical and called himself the father of jazz. He was a prolific songwriter and documented the hundred or so songs that he wrote. Of particular note is his song “Buddy Bolden’s Blues.” Morton moved from New Orleans to Chicago and jazz moved with him. He had a long career which lasted until his death in 1941. From my perspective, Buddy Bolden is the father of jazz and Jelly Roll Morton is the one who put jazz on the map.

The US and Canada: Country Music

Jimmie Rodgers (not to be confused with the person of the same name who sang “Honeycomb” in the 1950s) is widely regarded as the “Father of Country Music.” He was born in 1897 and died of tuberculosis at the age of 35.

Rodgers recorded over 100 songs during his tragically short career. He created a yodeling craze in popular music and some of his songs were called “blue yodels.” “T For Texas” (also called “Blue Yodel No. 1”) was a major hit in 1927 and it was this recording that created the yodeling craze. The first three inductees into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1961 were Rodgers, Hank Williams, and Fred Rose. (Rose was Hank Williams’ producer and a prolific songwriter.) Rodgers is also a member of the Rock and Roll, Blues, and Songwriters Halls of Fame.

Countless artists have cited Rodgers as a major influence, Gene Autry, Bill Monroe, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, and Dolly Parton among them. Bob Dylan put together a tribute compilation of major artists honoring Rodgers and covering his songs. In addition to Dylan, other contributors to that album include Willie Nelson, Jerry Garcia, Bono, Aaron Neville, and Van Morrison.

Europe: Flamenco Music

I always begin my discussion of flamenco music with, “This is probably the least-reliable information I am giving you on this tour.” More about that later. In the year 711, the Moors (Muslim Berbers from North Africa) invaded Iberia and conquered about two thirds of the Iberian Peninsula. Over time, the Spanish and Portuguese militaries retook much of this land. The last 250 years of their occupation, the Moors controlled the southern region of Spain known as Andalusia. It is here where we believe flamenco music began. The Moorish military left Iberia in 1492, almost 800 years after the initial invasion. However, after all that time, many Moors had deep roots in Andalusia via extended families, established businesses, and land ownership, and chose to remain in Iberia.

Flamenco music is primarily Gypsy music, with documented Jewish and Muslim influences. The Gypsies originally came from northern India, having started their migration sometime between the sixth and 10th centuries. The origin of the word “Gypsy” is interesting. Similar to how Europeans mistakenly called the indigenous people of the New World “Indians,” Europeans thought that the Gypsies were native to Egypt! The Gypsies are trying to shed that misnomer and in recent years have promoted the term “Roma,” which means man or person in their native language. (This has helped to fuel the misconception that the Gypsies are of Romanian or other Eastern European ancestry.)

Many Roma ultimately settled in Andalusia, most coming through Europe and others via Africa. So how did the Jewish and Muslim influences find their way into flamenco music? Roma, Jews and Muslims were the primary targets of the Inquisition; Jews and Muslims for religious reasons but the Roma for their lifestyle. The Roma typically adopted the religion prevalent in their environment, so most of those in Andalusia were Christian. However, the Spanish disliked their lifestyle and would rather have had them be serfs on farms. It is thought that rather than succumb to the dictates of the Inquisition, people from these three groups fled to rural areas where the police would not follow them. In so doing, they became neighbors and friends and it is believed this is how Jewish and Muslim influences found their way into flamenco music.

“Café cantante,” by photographer Emilio Beauchy circa 1888. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/CARLOS TEIXIDOR CADENAS.

Original flamenco music was comprised of simply singing and banging sticks on the floor. Subsequently, the performers put nails in their shoes to simulate taps, and clapping and other instruments were added. The last instrument to come into flamenco music was the Spanish guitar.

So, why is this information arguably less reliable than other information in this article? The Roma do not transcribe their history. It is passed on by word of mouth. This is compounded by the fact that the Spanish viewed flamenco music to be obscene, the result being that there wasn’t a word written about it until the late 1700s. Anything we know about flamenco is from writings hundreds of years after the fact, and important information must surely have been lost along the way.

Africa/Middle East: Marching Bands

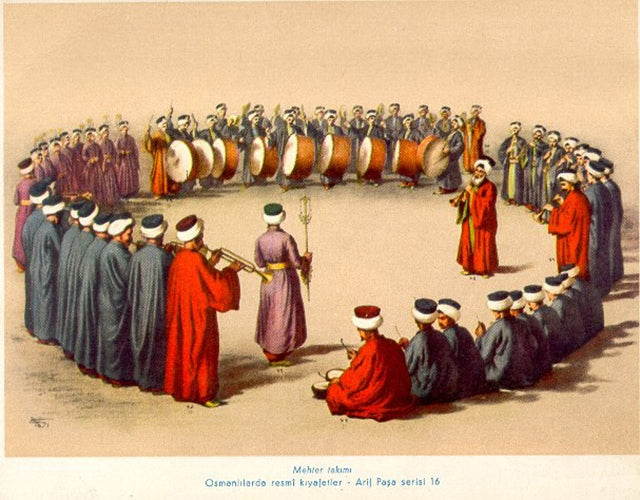

Many people believe that John Philip Sousa invented marching band music. That honor rightfully belongs to the Turkish mehter military ensembles who predated John Philip Sousa by almost 600 years! In fact, the date of the first mehter performance is known. In 1299, Osman I was coronated as the first Ottoman emperor. There was a very powerful sultan who was a major supporter of Osman I and his gift at that ceremony was the mehter.

The mehter became an institution with Osman I and, more generally, in the Ottoman Empire. As that empire spread into Europe and elsewhere, military marching bands became more prevalent. Ultimately, marching bands found their way into non-Ottoman countries and, today, virtually every military in the world embraces them. The concept of marching bands ultimately spread to the civilian population. In the late 1800s, it was a staple of American entertainment, with marching bands becoming fixtures in parades but also in non-marching environments such as park bandshells and auditoriums. John Philip Sousa’s own civilian band rarely marched.

Did you ever wonder why college marching bands usually wear strange outfits with odd, often plumed hats? Those costumes are derived from those worn by the mehter.

Mehter band. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/National Library, Ankara/public domain.

Asia: Knobbed Gongs

At MIM, we have standardized our definition of instrument types in accordance with what vibrates in the instrument to make music. The gong is an example of an idiophone, where the entire object vibrates. Idiophones can be constructed from any hard object: metal, wood, shells et al. We even have an idiophone at the museum that consists of the jaw of a horse and a metal spike.

The history of the gong is somewhat mysterious but it is thought to have emerged about 4,000 years ago. Some gongs have a knob or nipple in the middle and most experts believe that these gongs originated in Indonesia. The country has a rich musical tradition and their gamelan is an orchestra that makes extensive use of gongs. Indonesians revere the gong and believe that every instance of a gamelan orchestra has its own unique soul which resides in the largest gong.

Indonesian Kempul gongs. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures.

Gongs are usually made of bronze or brass, but the better ones are bronze. Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin with a “special sauce” of other materials often added. The Bronze Age came directly after the Stone Age and began around 3,300 B.C.E. What drove the Bronze Age was that bronze is a very hard material and was much better than its predecessor, sticks and stones, for making weapons and tools. Once people started working with it, they found other uses, such as utensils, jewelry, and statues.

Bronze has three advantages over brass with respect to idiophones. First, it is harder than brass and won’t dent as easily. Second, bronze does much better with the elements. Indonesia consists of 18,000 islands and beaches and salt water pervades that country. (I did a tour for a group of retired Navy guys and they pointed out that the propellers on their battleship were made from bronze.) Third and maybe most importantly, if you form bronze correctly and hit it with a stick or a hammer, it will have a better tone than brass. It will vibrate with more pleasing overtones. For those reasons, if an idiophone is made out of metal, bronze is the material of choice. This is also true for cymbals. The good ones are made from bronze, the cheaper ones from brass. Just about every church bell in the world is made from bronze.

Latin America: Panpipes

Another instrument type is the aerophone, where air vibrates to make music. A very early aerophone is the panpipe, which originated during the Stone Age around 4,000 B.C.E. The siku is a type of panpipe that arose in Peru and Bolivia in the vicinity of Lake Titicaca.

Lake Titicaca is in the Andes Mountains and covers an area of 3,000 square miles at an elevation of more than 12,000 feet. In Peru, there are 26 mountains over 20,000 feet high. As a comparison, the tallest mountain in the US outside of Alaska is Mount Whitney, about 15,000 feet high. Alaska has one mountain over 20,000 feet. Andean communities are fairly isolated due to the ruggedness of these mountains, and the snow and snow melt. Accordingly, each community developed its own unique siku music, with subtle differences in how the siku is constructed.

Playing a siku. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Gianni Careddu.

A siku can be made from many materials but is typically constructed from bamboo, cane, or reed. Many people think that these are types of wood but they are not; they are hard grasses. The advantage to using hard grass versus wood for an aerophone is that hard grass is hollow by nature and, accordingly, is very popular for aerophones in many regions of the world. To construct a siku, one cuts different lengths of hard grass and binds them together. Blowing into the longest pipe gives the lowest note and the shortest pipe gives the highest note. The musician moves his or her mouth from one pipe to another.

The siku is a one-handed instrument. Siku players sometimes use the free hand to simultaneously play a drum or perform some other action. Arguably the most important advance in aerophones over time is the enablement of the musician to blow into only one place without moving their head. To accomplish this, the other hand must be used to simulate different-size pipes. Depending on the design of the instrument, the musician may use that second hand to cover and uncover holes, open and close valves, or maybe operate a tube extender (as with a trombone) to create a full range of higher and lower notes.

The Musical Instrument Museum is a national treasure. Each of the 350 exhibits at the museum contains instruments and artifacts but also includes a number of videos, each telling a somewhat different story about the history and cultural significance of music. Here I have discussed some of my favorites, but there are many, many more stories to tell.

Header image: mehter band, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Michal Maňas.

0 comments