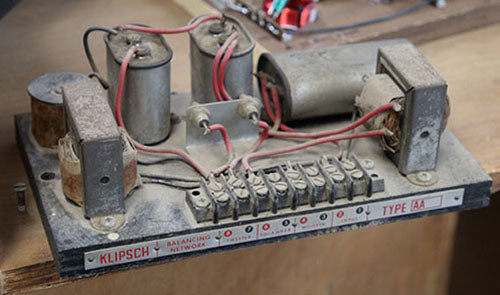

In my article in Copper Issue 141 I talked about my new setup using a Douk Audio USB digital interface to get an I²S output signal fed to my PS Audio GainCell DAC’s I²S input. Dalibor Kasac, my contact at Euphony Audio, the manufacturer of my streaming equipment, had mentioned to me in a few e-mails that they were working towards incorporating I²S capability into their equipment. He also told me that it would most likely be in the form of an outboard USB-to-I²S interface that they’d been working on with another European Union manufacturer located in Bulgaria. I’d mentioned to Dalibor that I had seen a USB audio interface online for just over $50 USD, but he strongly recommended that I pass on the Chinese-made gizmo.

But he also couldn’t give me any kind of timeline for the availability of Euphony’s outboard equipment, so I pulled the trigger on the Douk Audio interface, and it’s been nothing but a win-win for me. Especially since it allows me to play 32-bit/352.8 DXD files over my system, which was a capability I desperately needed for an upcoming review of an important release. However, there were some caveats with the Douk Audio interface in place in my system; mainly, for me, that I didn’t get any readout on my GainCell DAC as far as whatever the bit-and sample-rate of the digital file I happened to be playing at the time was. Of course, being as helpful as they are, the Euphony support people remoted in and confirmed for me that I was indeed achieving the correct high-resolution playback, so at the time that was enough for me.

But it wasn’t enough for some readers out there, who’d also ordered the Douk Audio interface and had encountered issues, the main one being that with certain DACs and/or streaming equipment, with DSD playback, the output channels were reversed. PCM was fine with everything, but not being able to easily get correct output of native DSD files was pushing some folks over the edge, and the manufacturer didn’t offer them much help to rectify the situation. Whereas everything was great for me, all the manufacturer could offer was that, unfortunately, their device just didn’t work perfectly in every situation. I felt bad about having given such a glowing recommendation to the Douk Audio equipment, and then having it not work perfectly for everyone. I do apologize that it wasn’t a game changer for everyone like it was for me.

Anyway, Dalibor reached out to me two weeks ago to let me know that they’d finalized their I²S solution, and had ended up going down a completely different path with it. Rather than going with an outboard box that still required a USB connection, they’d perfected a new internal card for the Euphony Summus Endpoint unit. They advised they would be shipping the new cards and remanufactured rear plates for the Endpoints that would not only accommodate I²S, but also an SP/DIF coax output for those who’d prefer to go that route with their DAC. I only had to send my unit to the US distributor (Arthur Power of Power Holdings) in New Jersey and he’d perform the update for me. It only took two days for my unit to reach Arthur, and about a week for him to get it back to me.

The really great news is that the new setup works flawlessly, and because the interface is internal to the Summus Endpoint, no USB cables are required on my end to get an I²S output to the GainCell DAC. It’s a less complicated and much more elegant setup, and amazingly enough, the GainCell DAC now displays the bit- and sample-rate information perfectly! And I have to restrain myself from gushing over the sound quality – while the Douk Audio unit performed admirably, the upgraded Summus Endpoint offers a greater degree of clarity and transparency than my Douk Audio workaround. If you’re in the market for a reference-quality music server/streaming setup, I give the Euphony Audio equipment highest marks, and their tech service is second to none.

New High-Res Disc Reviews

This issue, I’m looking at a few high-resolution CD/DVD-Audio combo releases that I’ve picked up fairly recently. Most of these have been out for several years now – some much longer than that, but have really only come to my attention in the last few months. I had been on a tear trying to grab every Steven Wilson Yes remaster out there, and just about everything he’s remixed and remastered has been made available in both DVD-Audio and Blu-ray sets. However, it seems like very early this year, the Blu-ray sets that were available for purchase very quickly disappeared; I was able to grab the Fragile and Close To The Edge Blu-rays, but had to get everything else (The Yes Album, Tales From Topographic Oceans, Relayer) on DVD-Audio. I can see no difference in sound quality between the two formats, but in terms of overall current system compatibility, the Blu-ray discs win out, and that’s probably why there’s been such a run on them of late.

So after getting all the available Yes titles, I started concentrating on my next favorite progressive rock band, King Crimson, and on finding as many remastered sets as possible, which are the 40th Anniversary reissues. Just for clarity, the “40th Anniversary” part refers to the 40th anniversary of the band, not the individual titles. I haven’t been able to completely determine whether the Steven Wilson remix/remasters were ever made available as Blu-ray sets, but I’ve been able to locate sources for the DVD-Audio/CD sets. But that only came after a protracted amount of effort. Most of these titles were released almost a decade ago, and have begun to become more difficult to track down. I’ve been able to acquire In The Court of the Crimson King, along with several Bill Bruford-era KC titles, including Larks Tongues in Aspic, Red, and Discipline, out of the ten (10!) titles Steven Wilson remixed. Those remixes are outstanding, and even though the highest resolution available for any of them is 24-bit/96 kHz PCM, the remix/remasters are miles beyond the standard catalog CDs. And it appears that Wilson and Robert Fripp worked on everything in the Crimson catalog up through the first iteration of KC that featured both Bill Bruford and Adrian Belew. So, there’s still a lot of collecting to do while these outstanding sets are still available (and still reasonably priced).

I also grabbed a copy of the DVD-Audio set for 1995’s Thrak, the last studio release that featured both Belew and Bruford, but I somehow managed to overlook the fact that it wasn’t remixed and remastered by Steven Wilson. It was in fact remixed and remastered by Jakko Jakszyk, who became the vocalist and second guitarist in the latest iteration of King Crimson in 2011, and remains in that capacity to this day. I’m surveying some of those releases this issue, and will continue with more Steven Wilson remix/remasters next time.

My reviews are limited to the high resolution stereo content; while others have raved about Wilson’s surround remixes, I’m not currently set up for high-end multichannel sound. I’ve got the correct loudspeaker setup, the perfect room, and plenty of great amps; I’m just lacking the proper complement of DACs and a great, affordable surround-capable preamplifier (virtually impossible to find!).

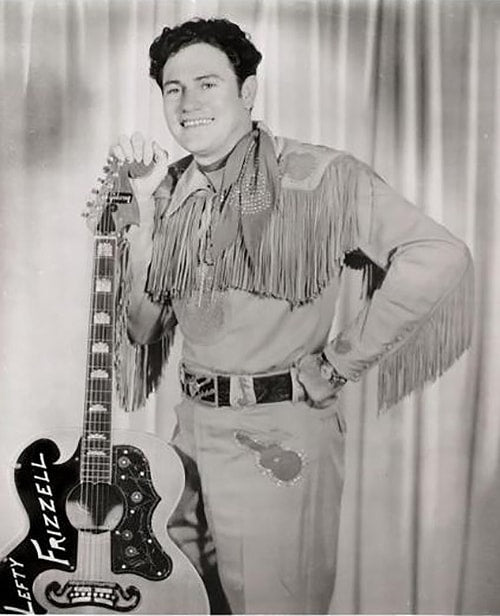

King Crimson – In the Court of the Crimson King (40th Anniversary Steven Wilson remix/remaster)

King Crimson’s debut album, In the Court of the Crimson King, is undeniably one of prog’s greatest records, if not the greatest. It still sounds just as fresh today as it did in 1969 – over 50 years later. iI was a truly remarkable achievement then and it still stands today as a landmark recording. Nothing needs to be said about it that hasn’t already been detailed in countless tomes.

That said, I’ve always been somewhat underwhelmed by the sound quality of the recording, but let’s take this into perspective – the album is over fifty years old! Still, it has ranked alongside a number of albums from the period that, for me, also offered pretty lackluster sound, including Jethro Tull’s Aqualung and Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (both have thankfully been updated with greatly improved remix/remasters in recent years). But several attempts by Fripp/EG Records at (digitally) remastering In the Court of the Crimson King yielded only marginal improvements over the course of several CD reissues, including the 30th Anniversary edition. How does the Steven Wilson remix/remaster compare?

Wilson’s modus operandi generally seems to include a much greater level of transparency and clarity, an improved level of instrumental textures and detail, and deeper, more well-defined bass. Those qualities are found in spades here, and there’s also a notable absence of the usual abundance of tape hiss, which has been reduced to an almost insignificant level. All of the above can be clearly observed in the quieter parts of the album, such as “I Talk to the Wind,” the latter portions of “Moonchild,” and the title track. The increased detail and improved positioning of the players in the soundfield is significantly enhanced, compared to the original and any subsequent remastering attempts. The really dynamic tracks, “21st Century Schizoid Man,” “Epitaph,” and again, the title track, are delivered more forcefully and with greater impact than on previous versions.

The included CD has multiple bonus tracks and alternate versions. And, as usual, there’s an abundance of extras on the included DVD, with not only the high-resolution MLP lossless 24/96 stereo and 5.1 surround mixes, but additional audio content as well. This includes the 24-bit 2004 remaster of the original tapes by Simon Heyworth, and a remixed “alternate album” comprised of outtakes from the original studio recordings remixed by Steven Wilson and Robert Fripp. The set also offers additional alternate takes, including the original full-length version of “Moonchild” that was edited by Robert Fripp for the original album release. There’s also a video of the 1969 Hyde Park concert version of “21st Century Schizoid Man” with the original mono soundtrack that’s both seen and heard for the very first time. And the online guys all seem to rave about the 5.1 surround mix.

If you’re a King Crimson completist, there’s a whole lot here that makes this set an absolute no-brainer, but for me, the 24/96 stereo tracks alone are definitely worth the price of admission. Which is currently still very affordable (about $20 or so online). A triumph on every level, this set is very highly recommended!

Discipline Global Mobile (DGM), DVD-Audio/CD set

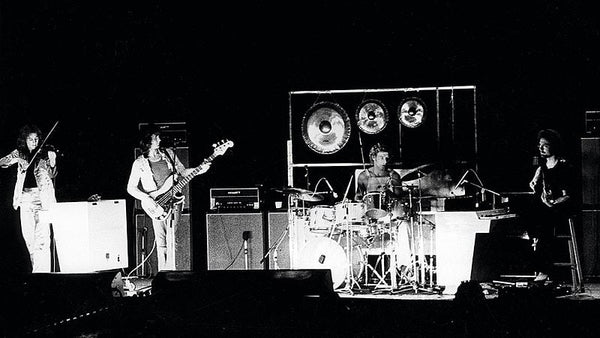

King Crimson – Discipline (40th Anniversary Steven Wilson remix/remaster)

King Crimson’s 1981 reboot with Discipline came seven years after their last studio album, which was 1974’s Red. Robert Fripp would only bring Bill Bruford’s drum kit along for this iteration of KC, which also featured American newcomers Tony Levin on bass and Chapman Stick, and most prominently, Adrian Belew on second guitar and vocals. Bruford’s drumming would feature his then-latest obsession, a Simmons SDX electronic drum set, although the song selection would highlight a mix of acoustic and electronic drums. Bill Bruford would reveal in a 2009 interview in Drumming that while he was definitely on board with electronic drums for almost fifteen years (1980 – 1995), it was a really hard grind getting them to do what you wanted them to do, and he ultimately abandoned them. Fripp had played with Tony Levin on Peter Gabriel’s first solo album, and he definitely wanted him in the next version of King Crimson, whenever that would happen. Levin’s work on bass and Stick added an entirely new dimension to the retooled Crimson sound.

The biggest change came with the addition of Adrian Belew, whose wild and unorthodox guitar style was a perfect foil to the usual Frippertronics. His songwriting and vocal histrionics also contributed mightily to the success of the new Crimson iteration. Fripp had been impressed with Belew’s work with both David Bowie and the Talking Heads, and when he and Belew met by chance at a Steve Reich performance, the stage was set for his future collaborations with KC. Adrian Belew was virtually not at all on my radar in 1981 when Discipline was released, and the album was such a radical departure from what I had come to expect from King Crimson that I was blown away by everything Belew brought to the band.

The Steven Wilson remix/remaster of Discipline is better than any version of this classic album I’ve ever owned, and that includes my original LP and a recent 200-gram reissue – which basically sounds great, except for the fact that it’s an awful pressing. The original Warner Brothers CD was just okay, and the DGM 30th Anniversary reissue CD was a definite improvement, but nothing to write home about. I always felt the catalog originals had more tape hiss than I was comfortable with, and I also hoped for better overall dynamics than they possessed. The remix/remaster has remedied those problems, and Adrian Belew’s vocals have never had more clarity and presence. A perfect example is the album’s centerpiece, the track “Indiscipline,” which was always very murky sounding and lacking in deep bass, and the dynamics of Bill Bruford’s drum kit was particularly emasculated. Everything that was previously missing (or obscured by the original mix) is now present, and Fripp and Belew’s guitars simply crush through the soundstage, while Bruford’s drumming pounds away furiously. Listening to the new remix of “Indiscipline” is literally like hearing it for the very first time!

The first disc offers the remix/remaster on a Red Book CD, which contains a bonus track and a couple of alternate mixes. The DVD-Audio disc contains both stereo and 5.1 multichannel 24/96 MLP lossless PCM tracks, as well as bonus tracks and videos for some of the music. The entire 30th Anniversary album mix is also made available, along with original rough mixes of album tracks. Not everything is presented in high-resolution sound, and the videos only have mono audio tracks. But for me, hearing Discipline in 24/96 stereo was an absolute revelation. This set is very highly recommended!

Discipline Global Mobile (DGM), DVD-Audio/CD set

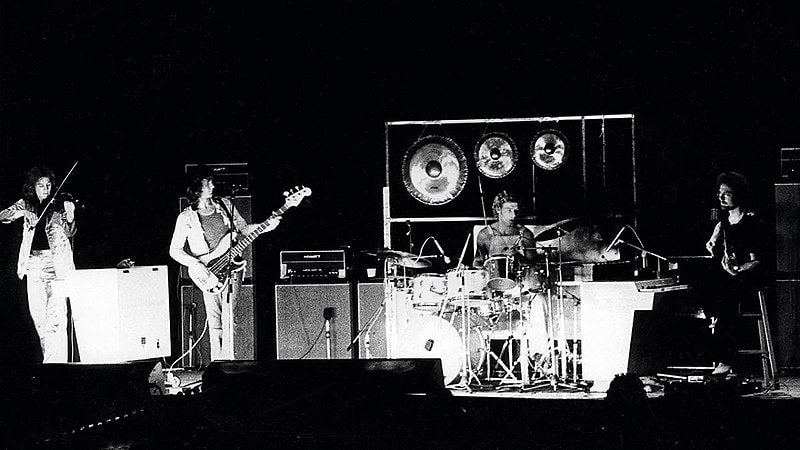

King Crimson – Thrak (40th Anniversary Jakko Jakszyk Remix/Remaster)

Eleven years passed between the last album from the eighties version of King Crimson, 1984’s Three of a Perfect Pair, and 1995’s Thrak. Fripp decided to augment the eighties lineup with two additional players, Trey Gunn on Chapman Stick and guitar, and Pat Mastelotto on drums. During the recording process, Fripp often referred to this lineup as his “dual trio,” although from all accounts, Bill Bruford wasn’t entirely happy with the proceedings. Bruford actually pulled Fripp aside at one point, reminding him that he (Bruford) was the band’s drummer. Fripp apparently told Bruford that in order to remain part of King Crimson, he’d have to cede all drumming creative control to Fripp. Bruford agreed, but Thrak would be his last studio album with Crimson, even though he did work with the band for two more years before deciding to pursue his jazz leanings full time.

The roots of the album came from the Vrooom EP, which had been released a year earlier. The new band convened in Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios, and for most of the album, the “dual trios,” consisting of a guitarist, bassist (though referring to the Chapman Stick as a bass is definitely an oversimplification), and drummer are each essentially split into left and right channels. Adrian Belew’s vocals are front and center in the mix, and Fripp also adds Mellotron to some of the tracks. Belew provided the lyrics for all of Thrak’s tunes, with all band members sharing credits for the album’s musical content. Thrak was generally greeted enthusiastically by the press and adoringly by King Crimson’s fans.

I always felt the standard CD release was pretty great, and the 30th Anniversary remaster was even better, so why bother with the 40th Anniversary remix/remaster? Which, as a package, is significantly less all-encompassing than any of the Steven Wilson-involved Crimson projects? Well, for me, the clear answer is Jakko’s new remix of the album, which brings out a greater level of detail and instrumental textures that I don’t hear in the previous CD releases. Adrian Belew’s vocals seem less congested; they were a tad murky on the CDs. The bass content was already thunderous on the CDs, but it actually sounds deeper and more refined here. And the placement of the players – even in the stereo-only mix – is more enveloping and provides a greater degree of realism. Again, I can’t comment about the surround content, although a number of people online have complained loudly about Jakko’s surround mix. But, I have to give a complete thumbs-up to the new stereo mix.

I was initially put off by, one, no involvement of Steven Wilson; two, loud online complaints about Jakko’s mixes, and three, the limited number of extras compared to the other Crimson DVD-Audio/CD sets (the only bonus here is the 30th Anniversary standard-resolution remaster). But this set – and especially Jakko’s stereo remix – has really grown on me. Highly recommended.

Discipline Global Mobile (DGM), DVD Audio/CD set

Summus Endpoint photo courtesy of Euphony Audio.

Header image of King Crimson courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.