Like vintage watches, pre-owned tapes are best appreciated with mint, original packaging. Ken Kessler finds they often disappoint.

It was our friend Jeff Dorgay at TONEAudio who first identified me as an “Audio Historian,” even going so far as to list me as such on the magazine’s masthead. Despite having written or collaborated on five books about hi-fi, and having inspired John Atkinson of Stereophile to coin the term “anachrophile” when we worked together at Hi-Fi News some 39 years ago, I had never considered myself worthy of such a career identifier. Me? An historian? My high school teachers’ laughs can be heard from their graves.

Atkinson created the anachrophile label for the then-new growth in interest in vintage hi-fi equipment – amazing to think this goes as far back as 1983. Why “amazing?” Because at that time, it must be remembered, CD was just about to hit the market, “digital” was the buzzword, the vacuum-tube revival was still a niche (though growing steadily), and elevated values for old, second-hand gear only applied to certified classics like Marantz’s Models 7, 8, 9, and 10, tube McIntosh amps, Tannoy Red and Gold monitors, and the like. Then as now, most hi-fi components depreciated faster than day-old bread. That a love for antique audio even happened is akin to a miracle.

Despite covering hi-fi classics now for nearly 40 years, I do not claim to be the first to have been fascinated by audio’s past. When I got bitten by the vintage bug, the industry was then still a young-ish 30-years-old, if you count its dawn as the first half of the 1950s. The extreme high-end was even younger, but by the time I learned to worship tubes in the late-1970s, the seeds had been sown for the creation of a vintage-gear-oriented underground: long before I started to write about classic hardware, the French, Italian, Japanese and Korean audiophile communities were peopled with those who loved, cherished, and honored such equipment.

Hence, Atkinson’s clever neologism “anachrophile” was warranted because there were enough of us globally to merit a category of our own. In those days before single-make histories were published, collectors were inspired and supported by academic studies from the likes of Japan’s Stereo Sound, with whole issues devoted to companies of McIntosh’s stature, and articles by noted authorities such as Jean Hiraga in France.

My vintage hi-fi fixation has remained a constant since the 1970s when – as an impoverished audiophile – I acquired a Rogers Cadet III tube integrated amplifier and a pair of Goodmans Eleganzias from a friend who was upgrading to Radford tubes and Spendor BC1s. This would later enable me to write books and produce articles from time to time on specific components from the past, based on hands-on experience, so it was inevitable that my rediscovery of open-reel tape would go beyond simply listening to a source I feel is superior to all others.

Naturally, it was the incredible sound of pre-recorded tapes which seduced me, regardless of the ordeal (and cost) of establishing a library of tapes sufficient to justify the acquisition of tape machines. It didn’t occur to me as I was seduced by the sound of Sgt. Pepper through Falcon LS3/5As, EAR electronics and a Denon DH-710 at the Tokyo International Audio Show in 2017 that I was about to embrace an obsolete technology with challenges not unlike the ownership of an Edwardian motorcar made in 1910, or a passion for plate cameras. But nothing would stop me, having once been bitten.

Denon DH-710 tape deck.

It is, however, in my nature to obsess about any new interest which attracts me. Over the years this has caused me to study wine, fountain pens, wristwatches, etc., instead of merely enjoying them for what they are, without the background information. Which brings us to one of the aspects of the tape revival which in turn both delights and frustrates, depending upon your level of geekiness.

One soon learns with open-reel tapes that not every box reveals some factual nugget to enrich our knowledge of audio’s first four decades. It’s worse than that: they tend to carry the absolute minimum of information. Despite commercial pre-recorded tapes being aimed more at enthusiasts than at casual users (if only because of the elevated prices), they suffered for the most part a dearth of liner notes, and not just about the recording technology: most tapes simply list the tracks, a situation made worse by an absence of songwriter credits, dates, musicians’ names, and other grievous lapses.

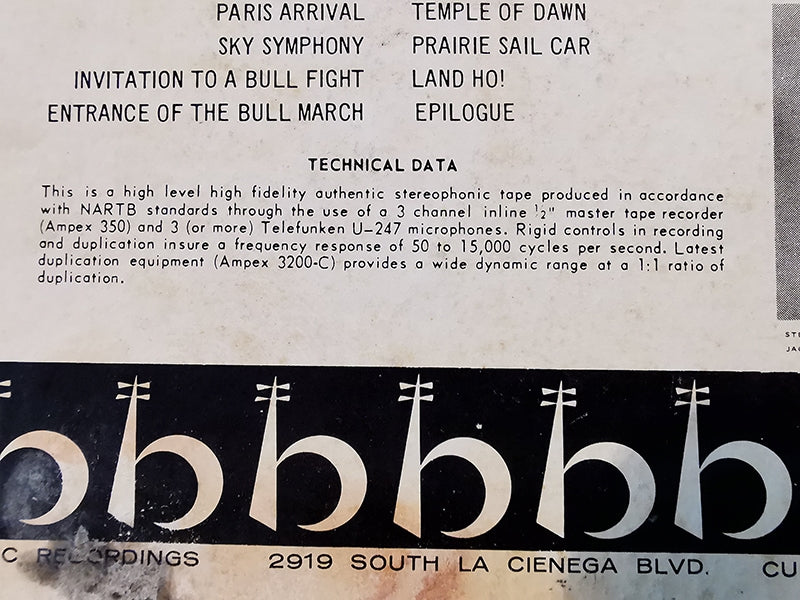

Let’s dispense right away with the tapes which did regale the owners with probably more data than they needed. The 1950s – 1960s specialist labels, in particular Audio Fidelity, Command, Everest and others which were present in the earliest days of the medium, printed information on the boxes or on separate inserts explaining how the sessions were recorded. Typical was Bel Canto’s specifications printed on the back of the boxes. This info also appeared on titles from other labels for which Bel Canto undertook the tape duplication.

For the curious audio enthusiast, the specs would explain that the tape was “produced in accordance to NARTB standards.” It would “insure a frequency response of 50 to 15,000 cycles per second.” Even more impressive were words to warm the cockles of any tape fetishist’s heart: “Latest 2 and 4 track Ampex duplication equipment provides a wide dynamic range at 1:1 ratio of duplication.” (Note that the labels used 2-track and 4-track to describe the formats, rarely 1/2-track or 1/4-track.)

Technical data provided for a reel-to-reel tape.

Cynics might point out that real-time duplication would have been financial suicide, and that high-speed duplication was probably the reality, simply for costs and expediency. All I know is that – as I sit here listening to The Lettermen tape, I Have Dreamed on Capitol, and it’s in the lowest-common-denominator format of 3-3/4 ips 1/4-track – the sound is simply staggering despite any economies taken during duplication, made even more incredible when one considers how pre-recorded open-reel tapes began as 1/2-track 7-1/2 ips. When compared side-by-side to the vinyl, the only listener who could possibly prefer the LP would be a cartridge or turntable manufacturer.

This brings me to a reason why most tapes suffered a dearth of information, though I am loath to defend the music industry. It’s worth noting that the premium labels, primarily with repertoires of classical, soundtracks, and some jazz, invariably included separate sheets, e.g., librettos, for opera tapes. This applied to record companies such as Columbia and RCA, not just the audiophile labels. But these were the exceptions. Confusion reigned when the vinyl LP’s artwork was reproduced in either exact or reduced form for the front and back of the tape box, and without corrections.

I’ve noted previously, for example, this happened when A-sides and B-sides were flipped, or – worse – when the track orders were changed, and more frequently than you might suspect. Sometimes the label glued to the tape spool would indicate the flipping of A- and B-sides. Aggravating this, though, is that early tapes rarely included the track listings on the spools because the stick-on labels were tiny, the contents listed only on the boxes.

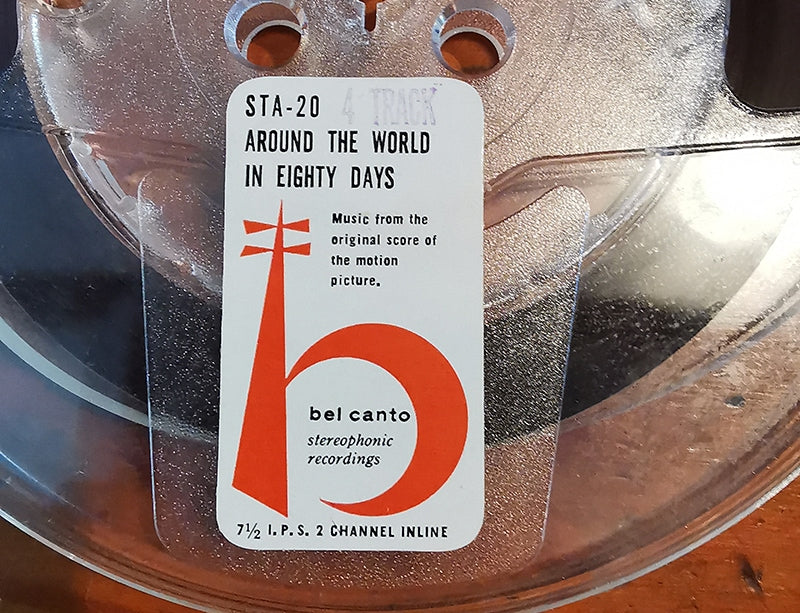

Read it if you can: a Bel Canto tape reel label.

Bel Canto was particularly diligent in this respect, despite the tiny stickers on the spools. Each box showed the song listings for both the 2-track and 4-track versions, the former usually containing fewer numbers than the latter. To indicate the speed, the box’s spine would have “1/2-track” printed on it, while an orange sticker would cover this to indicate a 4-track tape. The labels on the spools were printed with “2-track 7-1/2 ips” and rubber-stamped for 4-track. The boxes often added, “Also available on vinyl record” or LP along with the catalogue numbers.

While most classical tapes and those from specialty labels (regardless of musical genre) included either extensive liner notes printed on the back and inside the lid, or with 7 x 7-inch insert sheets, all the way up to multi-page booklets for releases which warranted them, e.g., multi-tape opera box sets, the vast majority offered nothing. Where this became a major loss for the customer is in the rock era.

Prior to the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, most LPs contained minimal artwork, with the tracks listed on the back, some with copious liner notes, e.g., Atlantic’s jazz LPs. As for the inner sleeves, these were often filled with a grid of LP covers from the labels’ other artists. Amusingly, those Capitol advertising-filled inner sleeves that came with Meet the Beatles, Beatles ’65 and all of the others prior to Sgt. Pepper’s pink-and-white inner sleeve (and sheet of cut-outs) now add value to second-hand copies, in the way that collectors of die-cast car models or vintage watches want the original packaging as much as the actual models or watches.

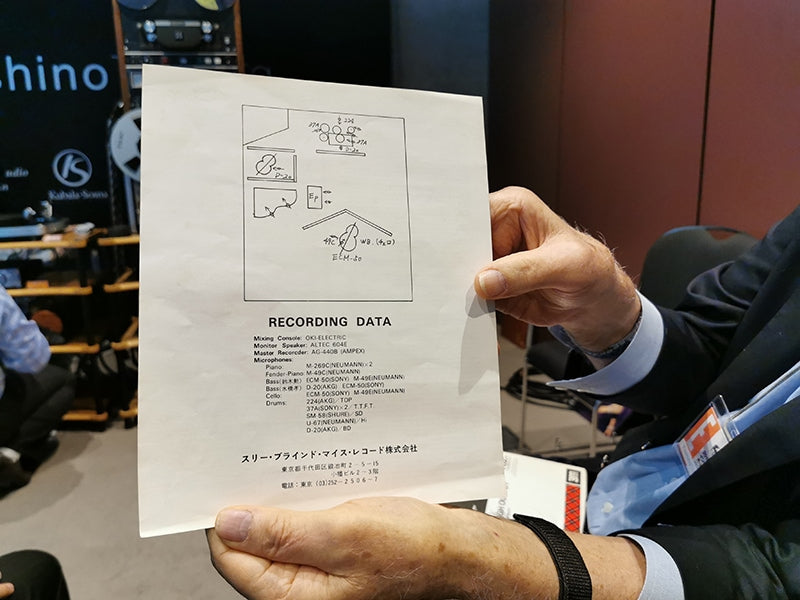

What was sacrificed for the tapes were all the goodies. For example, I have yet to find a single rock-era tape from 1967 onward that included even a printed facsimile of a special inner sleeve on a single-sheet insert. They certain didn’t bother to reduce any internal 12 x 12-inch artwork to add to the contents, the way that Japanese labels produce miniaturized reproductions of inner artwork for their deluxe CDs issued in card sleeves. As for Japanese tapes, just look at this photo of the studio layout which came with a Japanese pre-recorded tape a half-century ago:

Recording data insert for a Japanese pre-recorded tape, held by the late master, Tim de Paravicini.

Perhaps someone can provide further information, but working with tapes I actually own, I’m under the impression that the Capitol open-reel of Sgt. Pepper, for example, contained none of the LP’s inner artwork nor insert of cut-outs, nor does Magical Mystery Tour (which was really avoidable because it was originally a 7-inch EP with a booklet that was sized just right for inclusion in an open-reel tape box). As for Let It Be, forget it: the original UK release came with a proper book. Indeed, not one tape I have of an LP which was issued originally with deluxe packaging, or a printed inner sleeve or poster, provides such materials. From James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James to assorted Chicago and Blood Sweat & Tears albums, I guess we just have to make do with sound that blows away the other formats.

Header image: a selection of tapes from early specialist labels. Photos courtesy of Ken Kessler.

0 comments