J.I. began his overview of Danish-made Lyrec record cutting lathes in Issue 173.

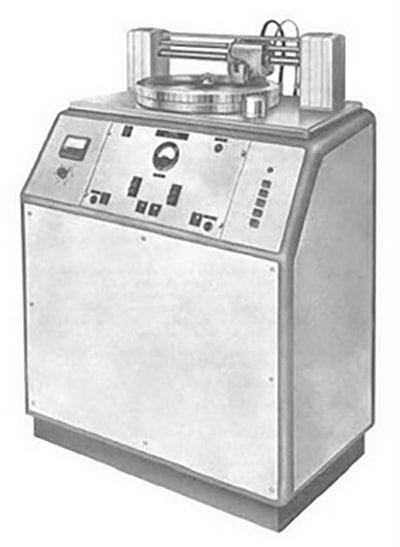

All Lyrec disk recording lathes, from the SV-2 to the SV-10, had similar features. They were all direct-driven by Lyrec’s own synchronous AC motors and featured massively heavy brass vacuum platters. They had a characteristic console shape, with an overhead carriage (located above the platter, instead of below, as was the case with Neumann and Scully lathes). The carriage was guided by a linear shaft system, with a leadscrew taking care of advancing the cutter head in the usual manner.

The cutter head suspension system was built into the carriage and featured a miniature vise clamp for holding the cutter head, which would come with a rectangular bar at the back that was designed to fit into the vise jaws. Although in the stereophonic era this would typically be an Ortofon cutter head, other cutter heads could also be fitted to a Lyrec lathe by using a suitable, custom-machined rectangular bar. However, the overhead design did not allow as much clearance and flexibility as with the Neumann and Scully lathes, since the space above the platter was limited by the presence of the overhead mechanism. As a result, massive heads such as those made by Westrex would not be able to be mounted with the correct geometry on the Lyrec suspension unit, even if a custom adapter was made.

The Lyrec SV-12 suspension unit, with the vise clamp cutter head mounting system. Courtesy of Electric Mastering.

Lyrec lathe with the covers removed, making visible the drive shaft and motor below the platter. Courtesy of Electric Mastering.

While the linear-shaft guide rod overhead system design was most probably first introduced by Fairchild (see Bill Leebens’ article in Issue 89 for an example of an early 1930s Fairchild Aerial Camera Corporation disk recording lathe, predating a nearly identical unit made in much greater numbers by the Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation) and also used by RCA (Model 73 and 73B) and Presto (Model 8D, 8DG and 14B) in a very similar configuration, a very similar concept had previously found application in ruling machines, and more importantly, in ruling engines used to manufacture diffraction gratings used in spectroscopy. In fact, in the industrial world the ruling engine is the machine with the highest degree of similarity in scope and scale to the disk recording lathe. Compared to the Fairchild (Model 199, 539, 523 and 740), Presto, and RCA incarnations of the guide- rod overhead mechanism, the Lyrec design was absolutely massive, and grew massive over time in later iterations. It was supported by two large cast pillars on either side of the platter and looked elegant and symmetrical.

The slanted front of the cabinet that the lathe sits on, contain all the electronic controls for the cutting parameters, along with large, distinctive meters – two meters in the earlier models and three in the later ones. The audio electronics, in the form of the cutting amplifier rack, were of course separate, as with all large lathes intended for professional use.

Lyrec lathe from a vintage brochure. Courtesy of Electric Mastering.

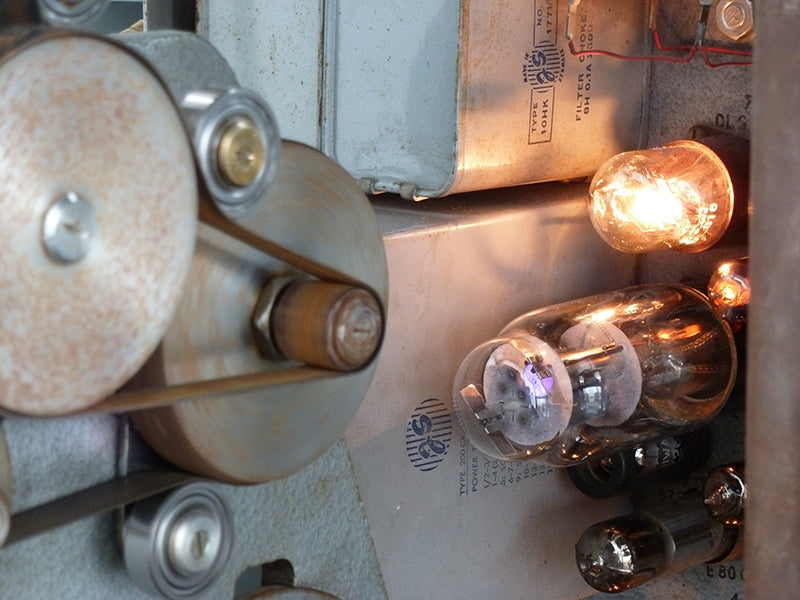

It was commonly accompanied by the Ortofon range of cutting electronics, which began as vacuum tube units and developed into solid-state designs. In the monophonic era, Lyrec also made their own electronics, but eventually left that up to Ortofon, still keeping it all-Danish, to be enjoyed with Anthon Berg chocolate, or perhaps croissants with Lurpak butter spread on them while they are still warm out of the oven.

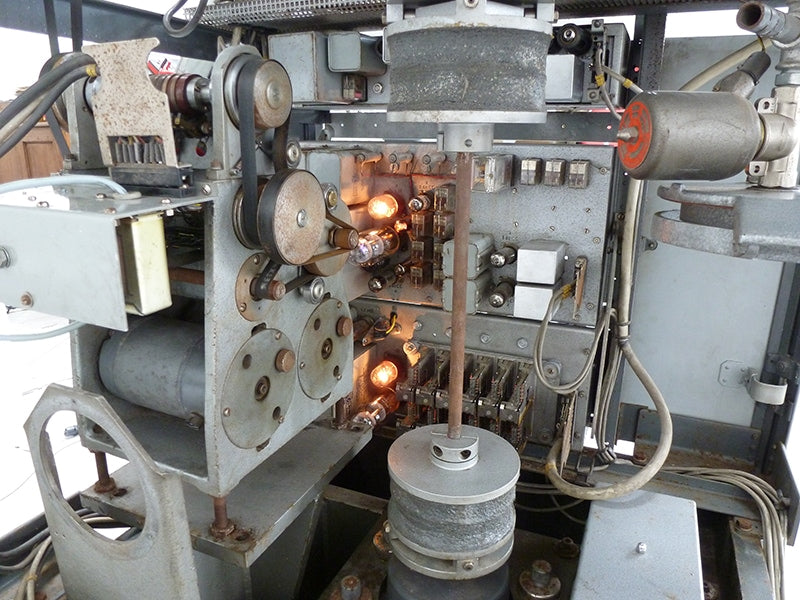

The first one of the three meters displayed the amount of current delivered to the stylus heating coil. On the later models, the meter in the middle would indicate groove depth in µm (microns, where 1 µm equals 0.00003937 inches). The suspension unit in these lathes contained a “depth coil,” which would allow the depth of cut to be adjusted electronically, usually automated by the onboard recording pitch and groove depth control automation system. This arrangement would only work with floating cutterheads and could not be used with an advance ball system (see Issue 162 and Issue 163 for further details on floating and advance ball cutter heads. The last meter would display the recording pitch in grooves per inch (GPI, which was exactly the same unit of measurement as the lines per inch (LPI) found on Neumann and Scully lathes. In fact, both are directly related to threads per inch or TPI, which is the standard English unit of measurement of screw thread pitch, which is the cylindrical equivalent to a vinyl record. An old phonograph cylinder could be considered a screw with a very fine thread. On the later Lyrec models, equipped with pitch/depth automation electronics, the pitch could also be automated.

The control electronics for the automation systems would require a “preview” signal, arriving 0.5 revolutions of the platter before the actual program signal would arrive at the cutter head.

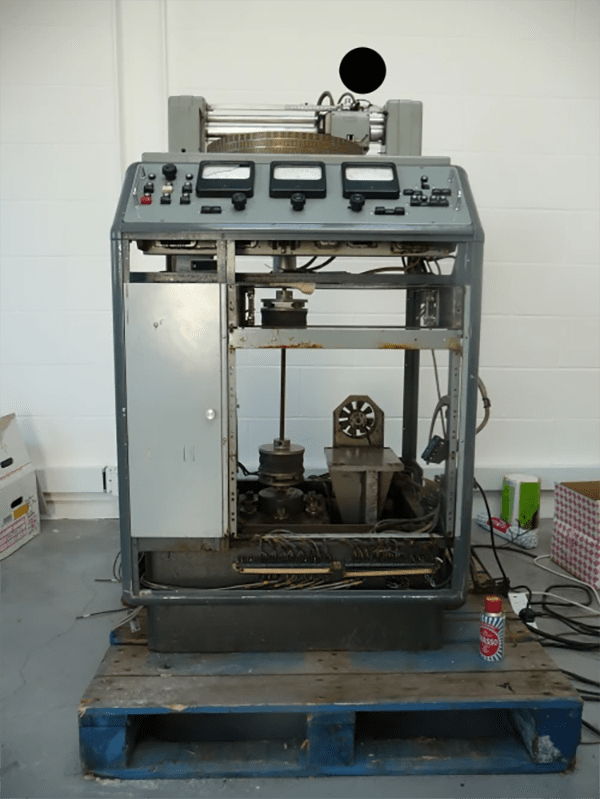

The Lyrec SV10 lathe at Electric Mastering in London, UK. Courtesy of Electric Mastering.

The massively heavy brass vacuum platter on a Lyrec disk mastering lathe. Courtesy of Electric Mastering.

This would typically be supplied by one of the Lyrec TR-range preview head tape machines (two different models were made for this application), since at the time, Studer, Telefunken, and Ampex only made preview head tape machines that were compatible with Neumann and Scully lathes, which did not use the 0.5-revolution delay time. It was much later on that Studer, Telefunken and MCI made versions of their machines that were compatible with the 0.5-revolution delay time, but that was because Neumann had decided to use this on the then newly-introduced VMS-80 disk mastering lathe, departing from the 0.5-revolution delay time of their earlier lathes. This 0.6-revolution delay time remained in use and was carried over to the VMS-82 DMM (direct metal mastering) lathe, but by that point the digital delay line had replaced most preview head tape machines in the field, and in any case Lyrec had entirely left the disk recording and mastering sector.

The choice of brass as the material for the vacuum platter on Lyrec disk recording lathes was very appropriate, if rather unusual. Most other lathes had cast aluminum platters, with some early units having cast iron platters. The platter was supported on an oil bearing and the driveshaft to the floorstanding Lyrec direct-drive motor had elaborate, sculpture-like elastomer decoupling disks, to prevent the transmission of vibration from the motor to the platter.

All in all, while not very well-known or widely used (only around 30 to 50 machines were ever made, all models counted in), Lyrec lathes were extremely sturdy machines, capable of exceptionally high performance. Some had found their way to the USSR, used in the Melodiya studios, perhaps to avoid having to buy American or German lathes. Melodiya eventually replaced these with Neumann lathes, which is probably what eventually led to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Detailed photo of the leadscrew drive system inside a Lyrec lathe. Courtesy of Electric Mastering.

Inside the Lyrec lathe: Leadscrew drive system, pitch control electronics and platter drive system. Courtesy of Electric Mastering.

Pete Hutchinson of Electric Mastering and Electric Recording Company in London, England has painstakingly restored a rare example of these fine machines, which the companies use for their all-analog transfers of original master tapes to disk, for their extremely high-quality reissues. As others have noted in Copper and elsewhere, their attention to detail is phenomenal, even down to actually utilizing traditional letterpress printing for the artwork!

If you want to hear what a Lyrec lathe is capable of, one of the Electric Recording Company releases or an early Melodiya record (up to the late 1960s) will demonstrate what these excellent machines were capable of.

Header image: two Lyrec lathes, originally used in Moscow, along with an Ortofon cutting electronics rack and a Lyrec tape machine. Photo courtesy of Edward Nowill.

0 comments