If there’s a more contentious topic in audio than that of horn loudspeakers, I don’t know what it is.—Okay, that’s not quite true: cables are a more contentious topic. I’m just not going there.

We’ve spent a lot of space in this column exploring the history of moving-coil loudspeakers from their creation by Jensen through their development at Bell Labs/Western Electric, the development of the acoustic suspension enclosure and dome drivers at AR, with detours through Weathers, Stan White, and Spica. We’ve also looked at electrostatic speakers from Quad and Acoustat, and those funky plasma drivers. It’s only fair that we take a look at horns through the years—and that will require revisiting Western Electric and its offspring.

Writing about the history of any field is a feat of genealogy in which family branches mysteriously break off, enlivened with a sprinkling of illegitimate offspring. Audio is like this, only ever so much so more so. Paths will cross and re-cross; familiar names will pop up again and again.

In order to understand horn loudspeakers, a little knowledge of their antecedents may be helpful. Going way back, the first horns used for sounding or making noise—I would hesitate to call them musical instruments—were formed from animal horns. The “trumpets” mentioned in the Torah, the Old Testament, and the Quran were not the brass, valved instruments of modern times, but likely a shofar or something similar. Generally made from a ram’s horn, a shofar is more like a bugle, really, as it is valveless and the player’s embouchure is the only control of the horn’s pitch.

The word “bugle”, interestingly enough, is derived from “buculus”, which is Latin for a castrated bullock—so the origins of bugles are clear. Like a bugle, a shofar has a conical bore, meaning that the inner sound-chamber is shaped like a cone, whereas flutes and trumpets (among others) have a cylindrical bore.

The first horns most of us encounter in life are also of conical bore: megaphones, including the rolled-up-paper versions often made in grade school. And of course horns can be used both ways—the hearing horn dating back t0 who-knows-when was essentially a megaphone in reverse.

The seventeenth century saw a number of polymaths appear in the worlds of science and engineering, and two in particular focused their attention on horns: Athanasius Kircher was a German Jesuit scholar who seemed to have studied almost everything, including microbes under a microscope. Kircher supposedly built “speaking trumpets” and proposed the use of room-sized horns to amplify the sound of musicians—although it’s not known if such giant horns were ever built.

A proposal by Kircher for use of a horn to “broadcast” the sound of musicians playing.

Kircher’s English counterpart was Sir Samuel Morland, who created a series of large speaking horns used by church choirs or orchestras. One such horn, known as the “Harrington Vamping Horn” (p. 154, right hand column) was said to be fully five feet in length, and still exists at its original church. Two other examples were said to be five and a half and six feet in length. Morland also worked in hydraulics and developed mechanical calculators and cryptographic machines.

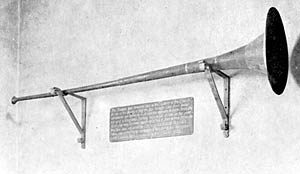

A similar tin horn, possibly not made by Morland, is still on display at East Leake church in Nottinghampshire. Eight feet long, it is clearly not of conical section, but is roughly exponential. It was supposedly in use by the church choir until 1855.

In the decades that followed, we saw the beginnings of horns associated with phonographic playback, with recording, and with playback by loudspeakers, as in the Western Electric horn shown in the construction plan atop this page. We’ll continue our discussion of horns in the next issue of Copper.

In the decades that followed, we saw the beginnings of horns associated with phonographic playback, with recording, and with playback by loudspeakers, as in the Western Electric horn shown in the construction plan atop this page. We’ll continue our discussion of horns in the next issue of Copper.

0 comments