Impedance. Signal to noise ratio. Driver size. Flatness of frequency response (or deviation from it). Sensitivity rating in dB. Cabinet size. Off-axis response. Power-handling capability. There are many considerations in speaker design and performance. Understanding more about all of these factors can assist us in making the best decisions regarding what speakers to buy when parting with our cash. And let’s not forget that minor little chestnut of an idea: ultimately, how good does it sound?

In this series, we’ll consider some of these factors and how they relate to real-world speaker evaluation. Seasoned audiophiles may be familiar with some or all of what we’ll be talking about, while other readers may find this information novel and enlightening.

Sound pressure level, or SPL, is literally the pressure level of a sound, which corresponds to volume, and is expressed in decibels, or dB. However, a more useful speaker specification is sensitivity, an indicator of how loudly a speaker will play at a given input of power. It’s expressed in dB and the higher the number, the louder a speaker will be when fed the same amount of power.

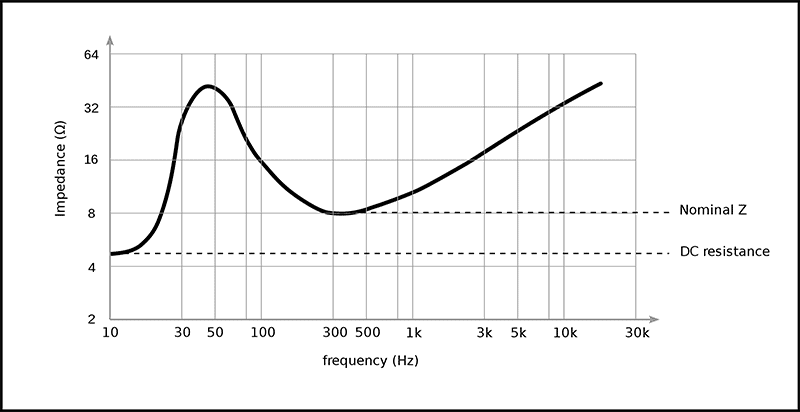

Typically, sensitivity is measured by driving one watt of power into an 8-ohm speaker at 2.83 volts, with the dB level measured from a distance of one meter. However, the rating by itself is only a rough indicator. Speakers are rated with an impedance spec, familiar to most of us, which is an indicator of how difficult the speaker is to drive. However, speakers don’t have the same impedance at every frequency – their stated specs are for a nominal impedance, but this can go higher or lower depending on the frequency the speaker has to reproduce.

That said, the industry standard of one watt into 8 ohms at 2.83 volts is a beneficial constant because it enables us to compare graphs of how the impedance of different speakers vary with frequency, and how their frequency response can be related. Because the impedance curves of various speakers can be so different, sometimes even within a given pair of drivers of the same model from the same manufacturer, having the consistent industry-standard “control” parameter of measuring sensitivity, gives you a baseline, and the ability to compare different speakers’ impedance and frequency response curves.

Also, some power amplifiers can handle lower impedances better than others. If an 8-ohm-nominal speaker dips to 4 ohms or lower impedance at some frequencies, your power amp or receiver may or may not be able to handle it (because it’s trying to deliver more current than it’s designed for), especially at higher volumes. Check your component’s power output specs to make sure.

That brings us to another consideration: an amplifier or receiver’s given power rating may not be particularly enlightening. The way manufacturers state their power ratings may not be consistent. You’ll see ratings like RMS power, peak (or instantaneous) power, average continuous power and others, and typically, the measurements will be taken when feeding the amp, a 1 kHz test signal, not music (with its full frequency range). However, none of these may equate to the optimal listening output you will enjoy at that power. It may not even fully reveal the actual headroom in power that the speaker system as a whole will be good for.

Historically, some manufacturers will provide the peak power rating of the speaker as its nominal power-handling rating, but won’t tell you that this is in fact just for a peak at one or a few frequencies. So, you have no clue as to the speaker’s real-world power-handling capability, or the range of volume levels and frequencies where the speaker performs at its best. I have personally experienced this with car power amp ratings being significantly exaggerated, both at peak music power output ratings and with RMS ratings. In other words, if you were provided with a wider set of information about the breadth of the bandwidth that a speaker operates at comfortably in terms of its impedance at different frequencies, and its true peak power handling capability, you’ll get a clearer idea of how well the speaker will reproduce the dynamics and pulses of your music. Many speaker manufacturers will provide an impedance-vs-frequency curve, and be forthright about their speakers’ power handling.

Graph showing impedance vs. frequency. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Spinning Spark.

Power ratings will obviously also vary according to the physical size of the speaker driver. If you are running a ten-inch driver it will require a different amount of power for its range of excursion. Generally speaking, more power will be required to move its greater physical mass back and forth compared to a 5.25-inch driver. Also, a smaller speaker will require more power to be as perceivably loud as a larger one. As the driver’s power requirements are different, so too, the maximum ability of the mechanical pistonic action of the driver will have a great influence on its maximum power handling and its peak output.

Other factors to consider are the speaker’s size, and your listening distance. Measuring a large speaker’s output at 1 meter will not give as meaningful a specification as measuring a smaller speaker at the same distance. That’s because I’ll bet you never listen to larger speakers that close up – but you might very well listen to smaller speakers at a distance of 1 meter, or closer. And of course, the farther away you are from your speakers, the louder they’ll have to play to deliver the same perceived volume as if you were closer. Some companies will take a measurement of a larger speaker at a greater distance than one meter, and then re-calculate what the sensitivity would be at one meter at 2.83 volts for the standardized and expected specification listing.

For those of us who own receivers with built-in room correction, we often just settle for having its processor accommodate for our set up of each speaker’s distance (and possibly frequency response) from our listening chair, and don’t have to think about any of this. But, wouldn’t it be nice to know as much as possible about how a speaker performs when looking at what to buy?

Some speaker manufacturers provide a range of optimum listening distances for a particular model, and this is very insightful piece of information, particularly for those with either significantly more or less cubic volume of listening space than average. Forgive me for sounding like Captain Obvious here, but when considering your potential speaker purchase, you likely have in mind the room that you will install them in, but the manufacturer, especially for something like a portable low-cost Bluetooth speaker, may have had considerations other than room size in mind. I wonder how many of even the most hard-core audiophiles have consulted the speaker manufacturers’ information on optimal room size compatibility, even when having a bespoke music room built. Although, to be fair, some manufacturers do offer appropriate product selection tools, such as REL’s recommended subwoofer selector, which allows you to enter a speaker model and room size and then comes up with a recommended subwoofer model.

How loudly do you want to listen to your speakers? You may find that typical listening volumes of 75 to 85 dB will suit you perfectly for most occasions, with occasional forays to 88 dB, for example. So, when you audition different speakers, it may be a good idea to measure them at the volume (and distance) you will actually be listening to them for the majority of the time, while using a dB meter or even a spectrum analyzer app.

One example is a very basic but effective Google Play app called Sound Meter. It provides a dB meter readout, and a list of familiar sounds and their typical dB levels, from quiet rustling leaves at 20 dB to a normal conversation at 3 feet (60 dB) right up to rock music or a screaming child at 100dB, and beyond (a Saturn V rocket launch registered 204 dB!). The app gives you some basic bearings to steer by as you measure your room at your seating position. It provides a graph mode and also a simple but functional dial display. Although it’s not the most accurate tool in the world, it will probably suffice for the testing purposes described above. In my own experience I have found it quite consistent. There are many other Android and iPhone apps available.

The Sound Level Meter app from SOFDX.

This can also provide you with some consistency in your comparisons when auditioning speakers, as you of course also listen for the musicality of the stereo speakers you’re evaluating. You may surprise yourself at just how quietly you enjoy listening to a well-set-up system.

We will consider the effects of the listening room more in Part Two, as it relates to sensitivity ratings and power output.

Header image courtesy of Pixabay.com/Tomislav Jakupec.