Elliot Goldman is a partner in Bending Wave USA, distributor of Göbel loudspeakers, Wadax digital electronics, CH Precision electronics and other ultra-high-end products. He’s been in audio retailing and distribution for decades and has seen and heard a lot. Part One of our interview begins here.

Frank Doris: Many readers might not know your background, so let’s get started with that.

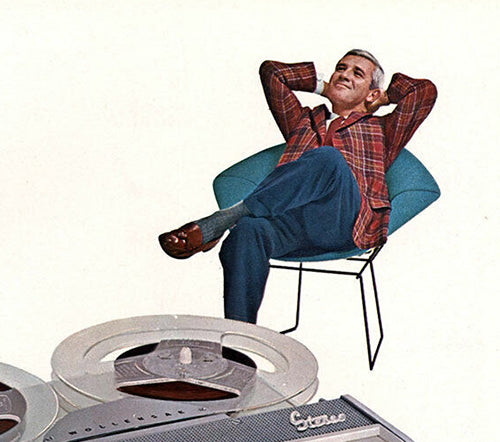

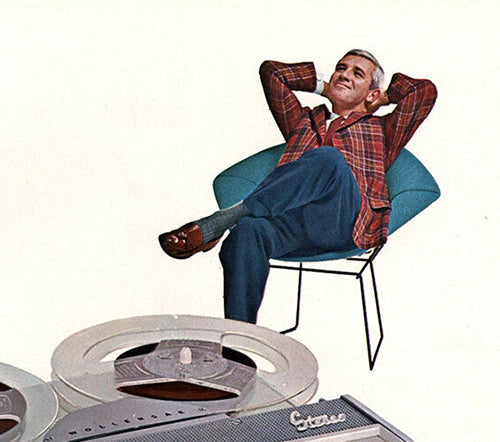

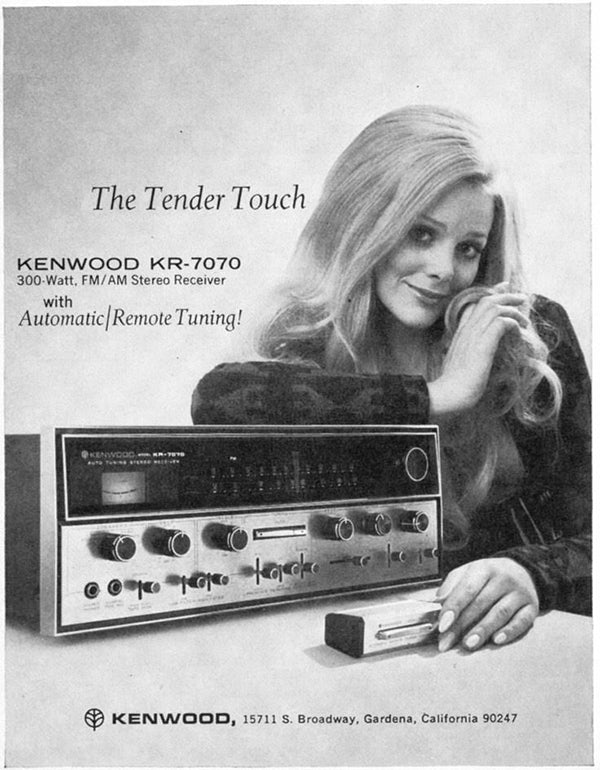

Elliot Goldman: After graduating from college, I kind of got interested in hi-fi kind of by accident. It happened about the same time I discovered marijuana. (laughs) I was invited over to some kid’s place and the first album I ever listened to stoned was Super Session with Al Kooper, [Mike Bloomfield and Stephen Stills]. Pretty amazing. When I got out of school, I really wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. I was thinking of going to law school and had worked one summer for a lawyer and found out that writing papers and reading books all day really wasn’t what I wanted to do. So, I started out [in audio] working for a company called Lafayette Radio.

FD: They were a big electronics maker and retailer based on Long Island.

EG: Right. Their main office was in Syosset. I went through a management training program, which was really great for me because it taught me how to run a business. My first job [for them], which was one of the best jobs I ever had in my life…they were going through an expansion [period], building a lot of stores. So I had a crew of four guys, and we were going from area to area, wiring all the sound rooms and displays and doing the initial store set up of over a hundred in a couple of years.

We had a really good time doing it and I certainly learned a lot. After that I became an assistant manager in Manhattan, then got transferred. I got married and was living on Long Island, and I really didn’t want to commute to Manhattan. So I got a job at a store on Long Island, and after working there for a while I met a guy and he offered me a job at [what was] at the time the first high-end audio store on Long Island, Sound Experience. That’s where I got introduced to Audio Research and Mark Levinson and Magnepan and Quad and Linn and all those other things. Eventually I opened my own store there, Audio Den which I and a partner had for a while, then [sold my interest in it]. And then I went to work for Lyric Hi-Fi [in Manhattan]. At the time, Lyric was really the temple of high-end, as you know.

FD: Yes it was. And it had a reputation…

EG: It was the preeminent store on the planet. This was around 1978 or ’79, and anybody who was anybody wanted to do business with Lyric. [Owner] Michael Kay was very generous to me. I always described him as my second father. It was a lot of fun. You name the company, we sold it, or [a manufacturer] wanted to be sold at Lyric. From that, I [started] my relationships with people like Arnie Nudell, Jon Dahlquist, Dick Sequerra, Jim Winey, Bill Johnson and on and on and on.

FD: Everybody.

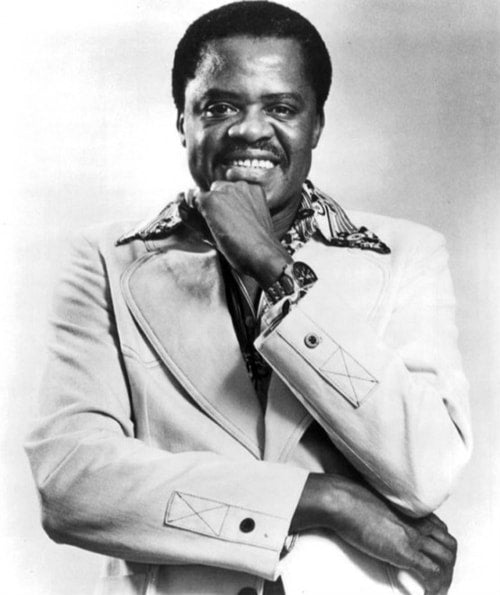

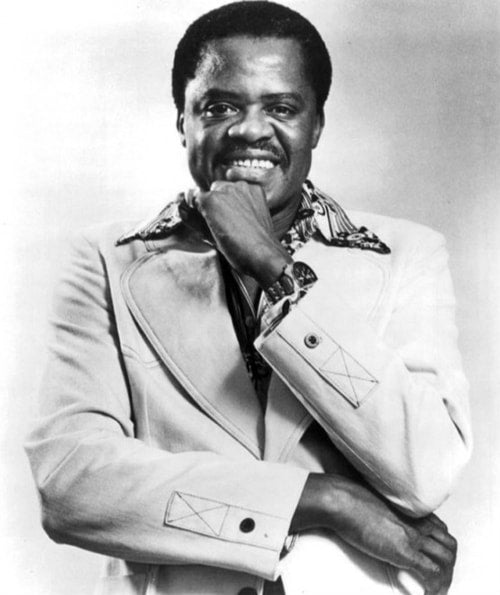

Yeah. And, and of course, Harry Pearson [founder of The Absolute Sound], who was my second mentor. Harry taught me a lot about how to listen and about music as well. [All of] that provided my background and my education and I’m grateful for that every day.

Harry Pearson in 1988. Photo by Bill Reckert.

FD: Obviously, Harry had a big effect on me, gave me my break, taught me a lot. [I got my start in the audio industry in 1984 as a writer for TAS – Ed.] He managed to piss a lot of people off too.

EG: Harry was a very difficult human being, and we were friends for a long time. Being friends with Harry Pearson, I don’t have to tell you, was extremely difficult (laughs) because he can be your biggest fan and then be incredibly rude. I regret that we were not close at the end. But he had seriously pissed me off when he wanted to do his own website and I was helping him, [and] really not making any money working for him. Trying to reinstitute what I thought was his birthright [as a founder of high-end audio journalism], which through his own ineptitude he gave away for nothing. But that’s a whole ‘nother story.

He kind of embarrassed and humiliated me about something and I said, f*ck this, I’m not doing it anymore. After that I moved to Florida. But I am grateful that I met him. I am extremely grateful for all that I learned from him. I am a staunch Harry defender whenever he’s attacked. I don’t think most people really understood him or what the world was like back then. I mean, look, he was no saint and no angel, and he took advantage of some of the circumstances, but I think more people took advantage of him than [the other way around}.

FD: Interesting idea.

EG: Well, everybody tried to take advantage of him at the time. Let’s go back and look at what audio marketing was in the 1970s and 1980s. Basically, most audio companies are small entrepreneurial entities, most of the time driven by somebody with some kind of technical background and not necessarily a sales background. And the only way they could get their product established was to get their product to a reviewer, particularly if it was Harry, and [have them] write something nice about it. And it made their company. Because they didn’t really have any marketing or promotion. Most of the time they didn’t even have a sales person. So Harry would come out and say, this cartridge is in his reference system, and all of a sudden everybody wanted to buy it. That’s changed a lot. I don’t think it necessarily works the same way anymore for a variety of reasons, which we can talk about later. But back then Harry was god.

Many of your readers maybe are a lot younger than you and I, [and they don’t know that] the industry was a lot smaller too. There was very few if any European products sold in the US, and very few high-end Japanese products. There were plenty of Japanese products, but not high-end products. The brands that were popular then and were important then were a much smaller pond to go fishing in than today.

FD: Getting back to Lyric Hi-Fi, because as you noted, some of today’s audiophiles might not remember this, but the store had the reputation of being rude and abusing customers and throwing people out. I remember at the time thinking, how can you do business like that? Is that really true or just something that audio writers wrote to stir up the pot?

EG: I don’t want to come off as a jerk, but it was very true. Having said that, they weren’t just rude [for the sake of being rude]. When I came to work for Mike Kay I was taught that we’re in business; we’re here to do business, we’re here to make a profit. There’s a lot of money invested in [the store], and we are not here to tolerate being taken advantage of or being treated badly. So I’m not going to say unequivocally that no one was ever treated badly at Lyric, because that’s not true. But I will say that the overwhelming majority of people that might have been treated badly probably deserved it. I’ll explain it this way. I don’t know how audio [retailing] became what it is [today]. What I mean by that is I don’t know how consumers expect that they can just go into a store and take up the people’s time they have no intentions of buying. Have you ever worked in a retail business?

FD: For a couple of years.

EG: I’ll give you two [examples]. If somebody walks into my place today and says, “hey, you know, I can’t really afford to spend a [lot of money] but I was wondering if I could come in and take a listen.” I don’t think I’ve ever said no to anybody like that. And when they’re honest with me I’ll play the system and give them a little of my time. But on the other hand, I’ve had plenty of people that pretend that they’re going to buy something when they had no intentions of purchasing anything, or they were using your showroom to figure out if they wanted to buy something they could buy used or from their friend, or to hear it and then shop all over the internet to try and find somebody maybe in another state or another country to sell it to them cheaper. I find that behavior repulsive. And the people that did that at Lyric got treated [accordingly and] asked to leave.

FD: If you remember Manny’s, the New York music store, they made it very easy. You’d walk up to the counter and the salesperson would say, “You looking to buy today?” And if you said no, “OK, next!”

EG: (laughs) We did that at Lyric too. I mean, as you remember, the original Lyric store was pretty small; I don’t know, about 20 by 50 and [it] had a basement. So, we basically had two rooms and everybody had to walk through everywhere to get everywhere. There was no real privacy. There was an entranceway and then to a door into the first room. And through the first room was a door to an office and a bathroom, and then a door into the back room. Everybody coming up the stairs had to walk through those rooms. We could at most help one or two people at a time. And Lyric was incredibly busy then. On a Saturday morning there could be 20 or 30 people waiting on the sidewalk to go in.

So, you had to separate the “tourists” from the buyers, because at the end of the day, Mike Kay paid me to sell goods and to make money. I don’t know how audio became this lending library and [customers got the idea] that everyone’s time isn’t worthwhile. I don’t want to sound bitter. I’m not; I just think that people need to think about being honest with people when they go [into a retailer].

I don’t consider myself a retailer anymore. I got into what I’m doing to be a distributor and kind of stumbled into [selling] some of the other products, because I needed to support myself, particularly during COVID. Trying to get a distribution company off the ground today is, especially with really expensive products, not easy.

I want to say this in the right way because I don’t want to offend everybody, but I think being honest with yourself and being honest with the people that you’re doing business with will get you farther than [doing the opposite]. I had a lot of people come into Lyric who were extremely rude. Fortunately for Lyric, we didn’t have to tolerate that and you would get asked to leave. On the other hand, particularly when it wasn’t busy, if you walked in and said “you know, I can’t afford an IRS V [Infinity speaker system, considered the ultimate loudspeaker at the time], but would it be possible for me to hear it?” Almost a hundred percent of the time somebody would play it for you.

FD: Tell us about some of the product lines that Bending Wave carries today. Obviously Göbel, because Oliver Göbel is the founder and a partner in Bending Wave.

EG: I was out of the audio business for a couple of years. The recession hit my company, which was called Front Row Center. It became difficult for both me and my partner to make a living. He [handled] the installation portion of the business and wanted to continue, so it morphed into Front Row Theater. I went to work for another dealer and really didn’t like that situation very much. Then I worked for an internet watch company for a couple of years. I wanted to learn more about doing business on the internet anyway. I was doing well there and probably would’ve stayed except they sold their company to a company in Philadelphia, and I wasn’t planning on moving at the time.

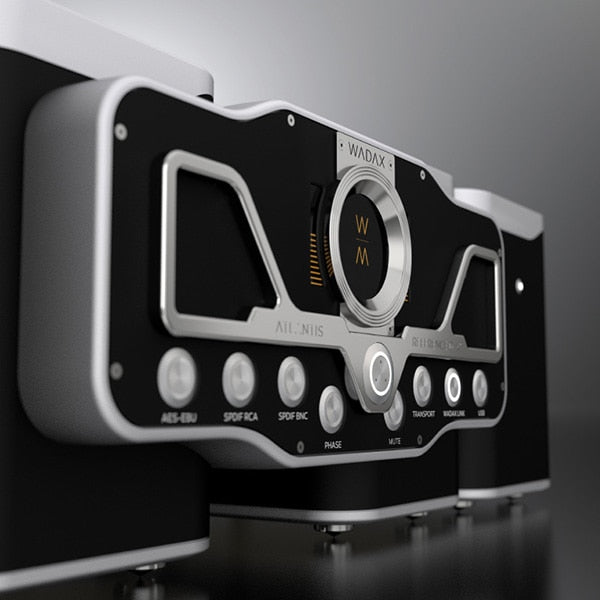

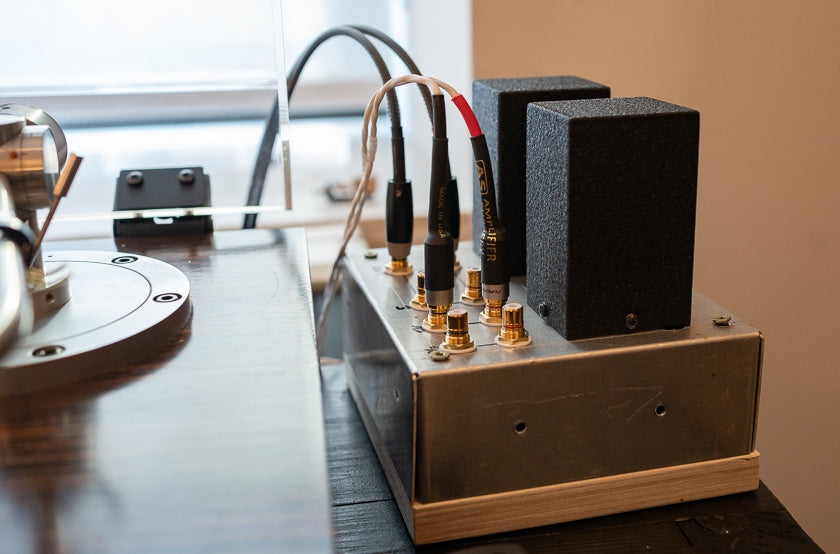

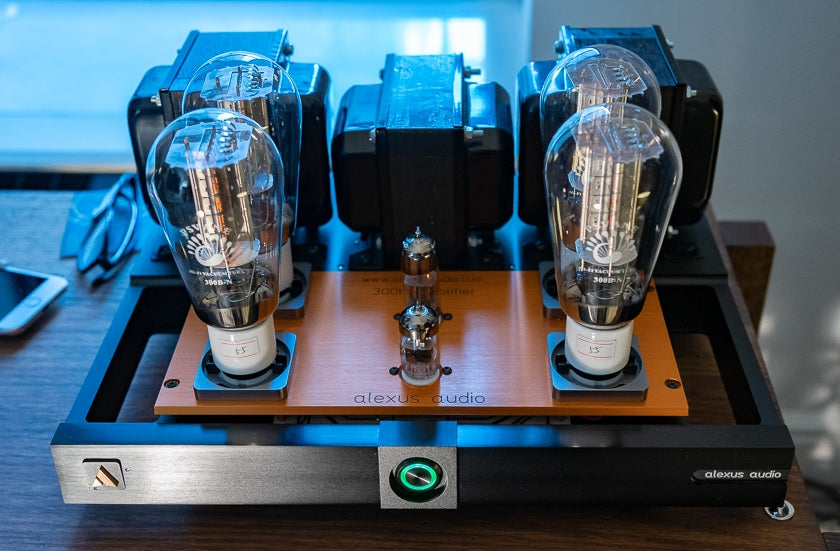

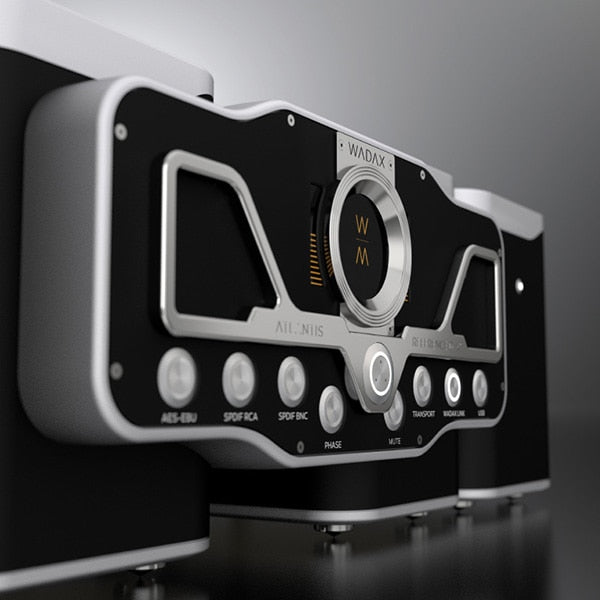

I happened to see something about a speaker made in Germany by Oliver Göbel. He was doing business in Asia and Europe but had never done business in the US. So I went to Germany, listened to the product and fell in love with it. We decided to distribute Göbel in the US. While setting up a showroom, I was looking for products [to complement the speakers]. I had seen CH Precision in Europe and really liked the sound of it. They were kind enough to send me some product to try once I was ready. I liked it better than anything else I had heard. I became friends with Fink Team at an audio show. Wadax kind of found me. In my opinion they’re the finest digital products on the planet.

We will be seeking dealers for Göbel around the country and introducing the new Divin Sovereign subwoofer at Capital Audio Fest. Göbel just opened a new factory outside of Munich and they’ll have two sound rooms open by probably early next year. I think every manufacturer should have that.

EG: Göbel speakers are as perfect as somebody can make a speaker in the fit, finish and packaging; everything is done to the point of no excuses. Having been in the ultra-high-end for the better part of my life, I’m constantly hearing from my customers things like, “I wish they had done that,” or, “I wish they had done this” when it comes to audio products. There’s none of that with Göbel.

FD: What in your opinion makes the speakers special? I know they use a full-range driver.

EG: Oliver has a patent on the bending wave driver used in the Aeon line of speakers. The Bending Wave driver goes from 160 Hz to over 30,000 Hz. It’s not a push-pull driver. Sound travels across the Bending Wave driver like it does on a piano soundboard. It’s the fastest, clearest driver that I am aware of. It has no phase issues because it’s not presenting in-phase and out-of-phase information at the same time, like a lot of push-pull drivers do. Its downsides are that it’s inefficient and requires a large amplifier. It’s expensive to make, and it’s expensive to make the baffle and all the other parts that it has to sit in.

There are different markets in the world and the largest market for his speakers has been Asia. But they’ve have been requesting for him to build something that was more efficient and easier to drive. So that was the beginning of the Divin series, which are 92 to 98 dB efficient and can be driven with small tube, or any kind of amps. From working with Bending Wave technology, Oliver learned how to build midrange drivers and woofers of a more conventional note using the Bending Wave technology.

I’m sitting in my sound room now with Divin Marquis, our entry-level speaker, and I have two Sovereign subwoofers. The Marquis work better in my room than the bigger Göbel speakers. I’m not saying they’re a better speaker, but a bigger speaker like the Divin Noblesse really belongs in a bigger room. There’s an optimal size for a speaker in a room. A speaker that’s too big for your room is not your best choice. I’m not saying it can’t work. But it’s really difficult to take a giant speaker and put it in a small room and make it work.

Divin Marquis loudspeakers.

FD: What kind of sound do you like to hear? What sonic attributes do you find most important?

EG: I don’t think there’s [any] one thing that’s important. I think it’s all important. I think a lot of audiophile [descriptive] terms have been corrupted. Harry Pearson tried to invent a language and I think that language has been corrupted or perverted. First of all, I want something to sound real. I am trying to create that illusion that I’m listening to real instruments. Harry Pearson’s original definition of “the absolute sound” is something I agree with: un-amplified music, acoustic instruments [in real life], but that’s not all the music I listen to. When I go to an orchestra or [a] jazz or rock [concert] they’re really very different.

There’s probably not a brand on the market, up until maybe a few years ago, that I haven’t represented at some point in time in my audio career. And there are more good products today than ever. But my sensitivity has always been to transparency and coherence. I want the speakers and the system to get out of the way. I want the system to get out of the way. I want to be able to listen through it and hear what the artist is trying to do, number one. Number two, I have found over years that the midrange and high frequencies are generally a lot easier to do than the low frequencies. Even the great speaker designers like John Dahlquist and Ross Walker and Arnie Nudell worked forever to extend what they were able to do [throughout the frequency range]. But the bass always sounded to me, on almost everything that I’ve ever heard, like it was an apple and an orange. When I go to a concert, and I don’t care if it’s rock or jazz or whatever, I, don’t hear the bass differently than I hear the rest of the music. It has detail, speed, a location. It has dynamics. And so when I finally got a chance to listen to Oliver’s speakers, it was the first time I felt that I was listening to almost the sound of a single driver.

I’m not a bass freak, but I love drummers and what drums and bass do to the music. There’s a lot going on there. I want to be able to listen through the music and hear what the drummer’s doing and what the bass player’s doing and listen to the guitar solo and listen to the keyboard. I think Göbel speakers do a better job of doing that in than anything else I have currently heard. I’m not saying everything else is bad and we’re good. It’s just this is the closest thing to what I want to hear.

FD: I don’t like a speaker that’s too bright or too “hyped” or forward. For me, tonal balance is the most important aspect of a speaker.

EG: Well, I think, Frank, [that] most speakers that are bright-sounding don’t have good bass. You go back to audio in the Seventies, and as [designers] were trying to get more information and more detail, the speakers became brighter [and] the electronics became brighter. And that’s not what real [music] does. The other part of the system that’s [extremely] important, of course, is the source. I’ve learned, particularly over the last decade, that all or most of the digital problems that people wanted to pick on in the Eighties and Nineties were really more [due to] the hardware than the software. I think that most Red Book CDs are much better than we gave them credit for back in the 1980s. It was specifically [because of] the hardware and not understanding their technology. That has changed. I think some of my oldest CDs sound amazing, now that the technology to play them back has dramatically changed…

Wadax Atlantis Reference DAC.

This interview, which will cover many more subjects, including the state of high-end retailing, reaching a younger generation, streaming audio, and much more will continue in Issue 176.

Header image of Elliot Goldman by David W. Robinson, Positive Feedback, copyright (c) 2022, all rights reserved.