Part One and Part Two of this series on desert island classical music albums appeared in Issue 172 and Issue 173. To recap: this list reflects my taste. Yours may be entirely different. In fact, it’s very likely. So, if you hate my choices, I totally understand. But we can still be friends.

My tastes run largely to orchestral music and opera, primarily from the late classical period through to the middle of the 20th century.

Wherever possible, I’ve tried to provide catalog numbers for the recommended recordings. However, since many recordings are available on vinyl, CD, SACD and as downloads, and each format has a different catalog number, it was not always possible. A quick online search should easily find the format you prefer.

This is the final installment in the series. Truthfully, if I was stranded on a desert island, I would want to have the entirety of my music collection with me. But this is supposed to be a series about the essential music that I couldn’t live without:

RACHMANINOV: Piano Concertos. Vladimir Ashkenazy, Bernard Haitink, Concertgebouw Orchestra; Decca

Vladimir Ashkenazy, now retired, is one of the great pianists of the second half of the twentieth century. A diminutive, unpretentious man, in concerts he would run (not walk) to the keyboard wearing a simple blazer and a turtleneck. When he sat down, poetry would flow from his hands. He had a particular affinity for the music of Rachmaninov and I was lucky enough to see him perform that music in concert on several occasions.

This recording represents Ashkenazy’s second full traversal of the Rachmaninov concerti (the first was recorded with Andre Previn and the London Symphony) and this is clearly the finer of the two. As always, Ashkenazy’s playing is sensitive and poetic and, where appropriate, fiery. Not surprisingly, Bernard Haitink and the Concertgebouw provide a loving accompaniment to this most expressive music.

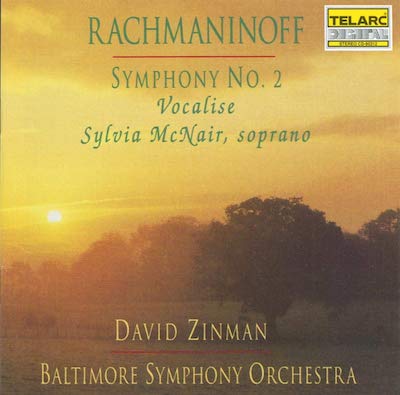

RACHMANINOV: Symphony No. 2. David Zinman, Baltimore Symphony; Telarc

If you attend enough concerts, every so often you will leave the concert hall having had a transcendent experience. I mentioned seeing Carlos Kleiber in Chicago, in 1978. That was one such experience. I had a similar experience back in 2014 when David Zinman guest conducted the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in this work.

I have a particular fondness for this unabashedly romantic symphony, proof – in my opinion – that Rachmaninov was more than just a great pianist. The orchestration is sophisticated, far more so than anything by that other famous composer-pianist, Chopin. And David Zinman has flown under the radar for much of his career. While he is a highly respected musician and teacher, he has never received the kind of recognition received by some of his peers.

That’s a shame because his recordings consistently reveal a talented, insightful conductor who brings music alive. This performance is a case in point. Like the performance that I attended, I can’t point to anything specific that he does. But all of the fine details are so perfectly etched that somehow everything comes together in a totally natural way, allowing the music to speak for itself, and it speaks volumes!

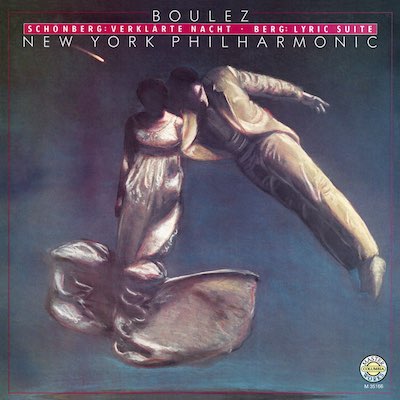

SCHÖNBERG: Verklärte Nacht. Pierre Boulez, New York Philharmonic; Sony Classical

Music was my college minor and as part of my studies those many years ago, we spent a great deal of time on the so-called Second Vienna School. I confess that, even after devoting considerable study time, I never developed a taste for 12-tone music. But Verklärte Nacht is an early composition by Schönberg, written before he created that system. And while it is richly chromatic, it is nevertheless a tonal composition.

Personally, I find it very moving, especially if you read the Richard Dehmel poem on which it is based. As in most modern music, Pierre Boulez excels in clarifying the textures, even when he is deploying a full orchestra on a piece originally composed for a sextet. The end of the work is particularly ravishing as the glistening strings seem to fade away into nothing.

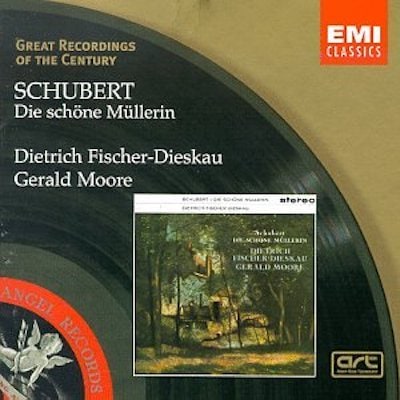

SCHUBERT: Die Schöne Müllerin. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Gerald Moore; EMI Classics (1961)

When one thinks of Schubert Lieder, there have been many great interpreters, but the name that immediately comes to mind – at least for us older folks – is the great German baritone, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. There are those who have criticized his singing as overwrought. But in Schubert, and particularly in the early part of his career when his voice was in its prime, he had no equal. He recorded the three great Schubert song cycles at least twice and performed them in concert many more times. But this early recording, with the great Gerald Moore at the piano, stands out as one of the greatest accomplishments in lieder singing. Die Schöne Müllerin scales the heights and plumbs the depths of emotion and Fischer-Dieskau makes that climb and descent with great aplomb and sensitivity, to say nothing of his golden voice at the height of his career.

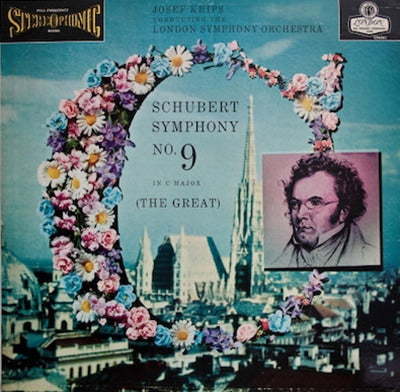

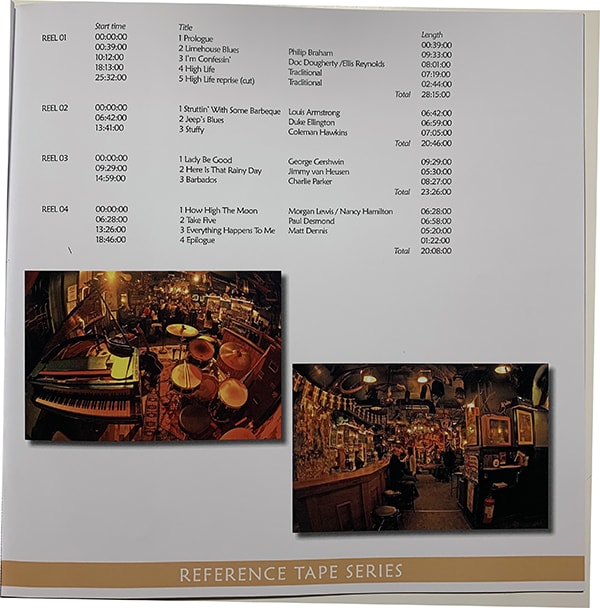

SCHUBERT: Symphony No. 9 in C Major (“The Great”), Josef Krips; High Definition Tape Transfers HDTT5003

Schubert’s final symphony seems a world apart from its predecessors, looking forward to the music of Schumann and Brahms, rather than an over-the-shoulders glance at Haydn and Mozart. Robert Schumann wrote about its “heavenly length” and at nearly an hour long, played with all repeats, it is certainly one of the longer symphonies in the standard repertoire.

This recording from May 1958 was the first recording of the work that I ever purchased, many years ago. Today I number at least a dozen recordings of this symphony in my collection, but this remains my favorite. The playing of the London Symphony is exquisite and Krips draws out every fine detail from this complex score. It was captured in excellent early stereo sound by the legendary Decca engineer Kenneth Wilkinson, and High Definition Tape Transfer’s restoration makes it sound like it was recorded yesterday.

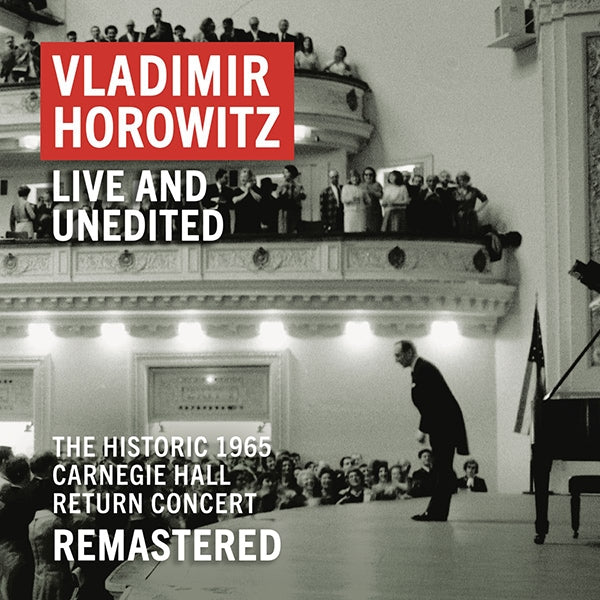

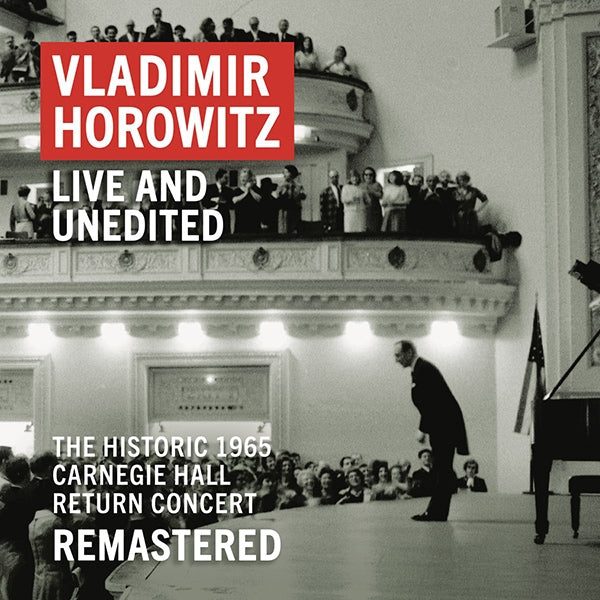

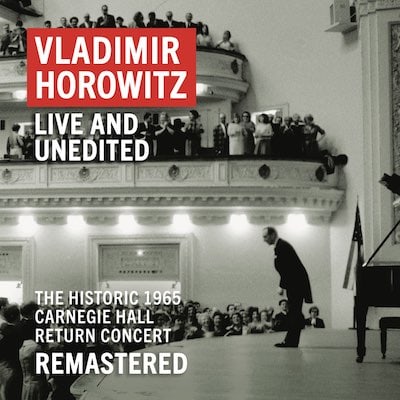

SCHUMANN: Fantasie in C Op. 17. Vladimir Horowitz; Sony Classical

In my younger days I studied piano for a number of years. I was never more than a mediocre student (not enough practicing, methinks), but I was always drawn to the music of Schumann and, in particular, this work. Unfortunately, I never developed enough skill to play the entire piece, but that in no way diminished my admiration for it.

My first introduction to this music was a long-lost LP set by Vladimir Horowitz, from his return to the concert stage in May, 1965, a recording which I recently purchased as a high-resolution download. I’ve heard numerous recordings of this piece, many of them very fine, including wonderful versions by Vladimir Ashkenazy, Maurizio Pollini, and Sviatoslav Richter.

However, as you may have gathered by now, I’m an old fart, and I’ve been around long enough to have heard Horowitz perform live. If you’re looking for a note-perfect performance, this is not it. It’s live and you can hear the occasional clinker. Vladimir Horowitz was never about perfection, as I can attest from seeing him perform. But his performances were always electrifying and I left the concert hall on a high every time I saw him. This performance is a perfect example of why. His articulation is crystal clear and the music exudes Schumann’s unique poetry.

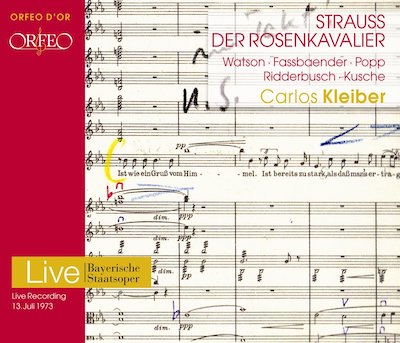

STRAUSS: Der Rosenkavalier. Carlos Kleiber, Bavarian State Opera, Brigitte Fassbaender, Claire Watson, Karl Ridderbusch, Lucia Popp, Benno Kusche, Gerhard Unger et al; Orfeo C581083D

Drawn from a series of live performances in Munich, this recording boasts a wonderful cast in excellent sound. The real star here, of course, is the late, great Carlos Kleiber, who made this opera one of his specialties. In fact, there are several different recordings of this work and this conductor floating around, including one from Vienna in 1994 and another on video with a slightly different cast. All of them are wonderful. Kleiber seems to possess a unique understanding of this music, imbuing it with charm, drama and humor. There are, of course, other very capable recordings of this music. But listening to Kleiber’s performances reminds me of something I once read about Bernard Haitink. When asked why he never conducted Verdi’s Otello during his tenure at the Royal Opera House, he replied something along the lines of, “Carlos Kleiber ruined it for me.” I feel much the same way about this recording; others pale in comparison.

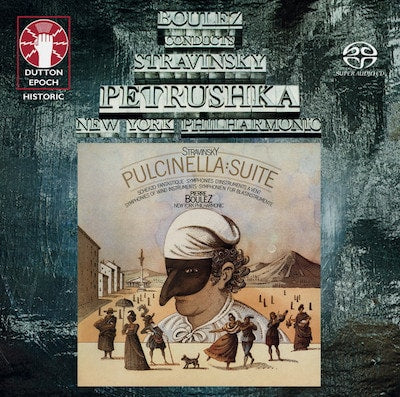

STRAVINSKY: Petrushka. Pierre Boulez, New York Philharmonic; Sony Classical

Pierre Boulez’ Stravinsky was widely praised for its clarity and its rhythmic certainty, in music that is notoriously difficult to conduct and play well. I love all three of Stravinsky’s early ballets (including also The Firebird and The Rite of Spring), but Petrushka is the one I heard first and it remains my favorite. Boulez recorded this work twice; this is the earlier recording with the New York Philharmonic made during his tenure as their music director. He conducts the original 1911 version for a large orchestra and draws responsive, virtuosic playing from his orchestra. Petrushka is a highly colorful ballet, and Boulez works tirelessly to draw those colors from the New York Philharmonic.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Symphonies 4, 5 and 6. Yevgeny Mravinsky, Leningrad Philharmonic; DG

Recorded by DG during a 1960 tour to London and Vienna by Mravinsky and his Leningrad forces, these are white-hot performances, in far better sound than Russian Melodiya was ever able to achieve. Mravinsky was a renowned interpreter of Russian music and, in particular Tchaikovsky, and he conducts these symphonies as if his life depended upon it. If you prefer cooler, more detached performances of this most romantic composer, these performances will probably not appeal to you. But you will never hear more exciting performances of this music. As an added bonus, you can still hear that unique brass and woodwind sound that Russian orchestras were famous for, before the worldwide homogenization made all orchestras sound more or less alike.

VERDI: Messa da Requiem. Arturo Toscanini, NBC Symphony; Pristine Classical PACO048 (Stereo)

This is yet another work that, as a chorister, I’ve been lucky enough to sing on a number of occasions, under conductors like Sir Andrew Davis and Gianandrea Noseda. As with Handel’s Messiah and Orff’s Carmina Burana, I have listened to a great many recordings of this wonderful, remarkable choral work.

But no modern recording – to my ears anyway – will ever match any of Toscanini’s performances of this masterpiece. Great conductors like Carlo Maria Giulini, Riccardo Muti, Georg Solti and many others have made multiple recordings of the Requiem and many of these are very fine. But they still do not approach the fire, intensity and passion of Toscanini. If you don’t believe me, listen to this restoration, in “accidental stereo,” made from two separate microphones that were in place during the original performances. Andrew Rose of Pristine poured many hours of work into creating a stable stereo image and cleaning up the original recordings. No other performance has so much forward momentum or – in the appropriate places – tenderness. Listen, for example, to the fire of the Dies Irae. Or to the string playing in the Sanctus; you will never hear such delicacy anywhere else. As an aside, Pristine has even managed to remove Toscanini screaming at the orchestra during the Tuba Mirum. I kind of miss that.

WAGNER: Der Ring des Nibelungen. Sir Georg Solti, Vienna Philharmonic; Decca

This is Decca’s groundbreaking recording of Wagner’s Ring, dating from the early days of stereo in 1958 with Das Rheingold, to Die Walkure recorded in 1966. Produced by the legendary John Culshaw and conducted by Georg Solti with youthful ardor, the cycle features the greatest Wagner singers of the post-war period including Kirsten Flagstad, Birgit Nilsson, Wolfgang Windgassen, Hans Hotter, Regine Crespin, James King, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Gerhard Stolze, Christa Ludwig, Gottlob Frick and many others.

When these recordings were first released, there was very little competition. Definitely none in stereo. Since that time, however, many recordings of the full cycle have appeared including those by Karajan, Haitink, Böhm, Thielemann, Barenboim and a host of others. I have well over a dozen different recordings in my collection.

In the decades since they first appeared, there has been a something of a revisionist trend to criticize these recordings as superficial or flashy. But this is the cycle I keep coming back to. The playing of the Vienna Philharmonic is glorious, the cast is clearly the finest on record, and if Solti is occasionally a bit brash, I find that this suits the ethos of these performances. By all means, listen to other recordings. But if you’re like me, you’ll find that these performances are ultimately the most satisfying.

A final note: in 1997, engineer James Lock made a 48/24 digital transfer from the original master tapes using the CEDAR de-hissing technology. All current issues of this cycle are based on that transfer. Decca maintains that the original masters are now too degraded to be used for any further transfers.

WAGNER: Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg. Sir Georg Solti, Vienna Philharmonic, Norman Bailey, René Kollo, Kurt Moll, Bernd Weikl, Hannelore Bode, Julia Hamari; Decca

I fell in love with opera at an early age. Every Saturday afternoon, without fail, my mother had her kitchen radio tuned to the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts, rain or shine. While my young ears were most familiar with the sounds of Renata Tebaldi, Leontyne Price, Franco Corelli and other luminaries of Italian opera, as I grew older, I found myself drawn more and more to the music of Richard Wagner (to my mother’s dismay).

Truth to tell, despite its gargantuan length (my copy of the score is at least two inches thick), Meistersinger is my favorite opera. Wagner’s only mature comedy, it is also his most human work. I have many recordings of it in my collection and, frankly, none of them is perfect (unless you count Toscanini’s 1937 Salzburg performance on Andante which is brilliant but in barely tolerable sound). Inevitably, one of the leads is less than ideally cast. For that matter, sometimes a minor character can sour the experience. I’ve heard too many recordings with a weak, woolly Kothner or Pogner. And sometimes, the conducting is just undistinguished, failing to do justice to Wagner’s glorious music. Perhaps, at some point, I’ll write a traversal of the various recordings that I’ve heard.

I love Silvio Varviso’s beautifully-led performance from Bayreuth (Philips), but Jean Cox (as Walther) ruins it for me. Similarly, I swoon at Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s intensely human Hans Sachs under Eugen Jochum (DG) but the rest of the cast leaves a lot to be desired. So after a great deal of listening, I’ve reached the conclusion that this, the earlier of Solti’s two recordings, has the fewest weaknesses of all the performances that I’ve heard. Yes, Kollo may be a bit overripe and Hannelore Bode sounds a bit matronly for Eva. But neither voice is unpleasant and the rest of the cast is very strong, especially Norman Bailey’s avuncular Hans Sachs. Solti leads with his usual attention to detail and a minimum of bombast and, as usual, the playing of the Vienna Philharmonic is wonderful.