Richard X. Heyman has long had a habit of paying homage to his various influences while simultaneously carving out new and exciting paths ahead.

In his earliest days in the 1960s, Heyman was the drummer for underexposed garage rock outfit, the Doughboys, before embarking in 1988 on a long and winding career as a solo artist entirely unafraid to tackle all genres. (The Doughboys reformed in 2000 and Heyman is still a member.)

Ever-busy, and increasingly creative in what may or may not be the twilight of his career, Heyman has followed up 2021’s indie slice of heaven, Copious Notes, with another outstanding studio affair, the just-released 67,000 Miles An Album. (See Ray Chelstowski’s review of Copious Notes and interview in Issue 137.)

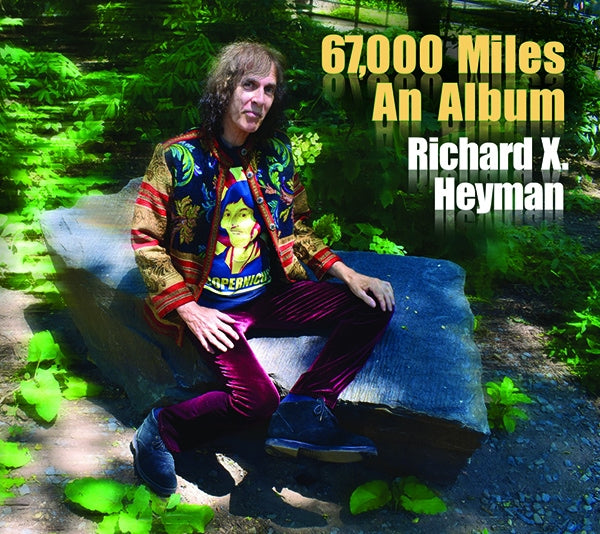

Richard X. Heyman, 67,000 Miles an Album, album cover.

While Heyman has no immediate plans to climb back up on stage, fans of the veteran indie rocker’s work will be well satiated with a delightful grouping of tracks with a subject matter aimed at just about anything you can think of. To be sure, 67,000 Miles An Album is an accurate auditory visualization, if you will, of Heyman’s inner machinations.

In the wake of this latest record, Richard Heyman dug in with me to discuss his early origins in music, the influences that most shaped his style, his songwriting process, his new music, and what’s next for him as he keeps moving ahead.

Andrew Daly: You’ve been at this for a while. What first sparked your interest in music?

Richard X. Heyman: My father was a huge fan of big band jazz like Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Count Basie and Duke Ellington, as well as of the singers of that era like Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald, while my mother was heavily into Broadway musicals. My three older sisters had their records of the burgeoning rock and roll scene lying around the house. And then there were the LPs and singles left by various boyfriends, partygoers, etc., so this eclectic mixture of vinyl was at my disposal.

I remember seeing and listening to James Brown’s Live At The Apollo, an early album of the Ike & Tina Turner Revue, One Dozen Berries by Chuck Berry, plenty of early Beach Boys, Dion and The Belmonts, and many more. On top of that, you had the ubiquitous AM radio – for me, it was WABC (though sometimes I’d check out WMCA and WINS with Murray the K). And, of course, the big 23-inch Zenith [TV], where I’d watch the various variety shows that featured all the genres mentioned above, and topped off by a respectable collection of the classics (Beethoven, Mozart, Gershwin, and that mob). So, it was just a matter of absorbing all these sources, which I readily soaked up.

AD: Who were some of your earliest influences?

RXH: Starting as a drummer in my youth, I admired Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Joe Morello, Elvin Jones, Louie Bellson, and an assortment of other great jazz drummers. Then I got into early instrumental rock music via the Ventures, and I was happily bashing away in a combination of those styles when out of nowhere, there was this bloke named Ringo. And that certainly took me in a new direction. Other rock drummers who influenced me were Charlie Watts, Dino Danelli, Mitch Mitchell, B.J. Wilson, Keith Moon, Bobby Elliott, and the behind-the-scenes session cats whose names I didn’t know at the time, but now I can give them their due: Hal Blaine, Earl Palmer, Clem Cattini, Bobby Graham, Panama Francis, Gary Chester, and Bernard Purdie.

As far as my general musical influences, at least in the realm of rock and roll, it was all the top-40 hits of the day which shaped the musical path I was to follow. More specifically, I would point out the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, the Beach Boys, Wilson Pickett, the Rolling Stones, the Supremes, the Byrds, the Temptations, the Who, Sam Cooke, the Kinks, Marvin Gaye, Del Shannon, Jimi Hendrix, Procol Harum, The Lovin’ Spoonful, Joni Mitchell, Martha and the Vandellas, The Mamas & the Papas, Gary U.S. Bonds, The Marvelettes, the Band, and too many more to mention.

I also want to give a shout-out to the pioneers of rock and roll – Chuck Berry, the Everly Brothers, Eddie Cochran, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Elvis Presley, Larry Williams, Buddy Holly, and Ricky Nelson (singing into our living room once a week on The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet).

AD: How would you say that style has evolved as you’ve moved through your career?

RXH: The style that most interested me was an amalgam of the Beatles’ melodicism and the lyrical invention of Bob Dylan. That combination started to influence the great songwriters of that era, like Ray Davies, John Sebastian, Pete Townshend, John Phillips, and Gene Clark, to name a few. So, I was inspired by the possibilities of delving into personal experiences mixed with a bit of storytelling over the top of chord progressions that I found intriguing.

AD: What were some of your earliest gigs where you first cut your teeth?

RXH: I started playing drums in a local band when I was 12. So, we’d mainly play house parties, and that led to school dances and opening up for a variety of recording acts. We performed on Zacherle’s Disc-o-Teen television show regularly. That band was called the Doughboys. We won a battle-of-the-bands contest on the show, which led to a record deal with Bell Records for which we released two singles and played dozens of WMCA Good Guys shows, alongside acts like Neil Diamond, The Shirelles, the Syndicate of Sound, the Music Explosion, and so on.

We subsequently were the house band at the Cafe Wha? in Greenwich Village in the summer of ’68. The guitar player from the Doughboys (Willy Kirchofer) and I joined the Quinaimes Band, and we toured as the opening act for Sly and the Family Stone, which kicked off at a sold-out house at Madison Square Garden. By the time I was through with that, I needed complete dental work from all that teeth cutting.

AD: Let’s dig into your newest project, 67,000 Miles An Album. Tell us about its inception.

RXH: After I completed my last album, Copious Notes, I decided to jump right back into the fire and start the next project. I’ve always found it amazing that [the Earth is] hurtling through space at 67,000 miles an hour. I thought about all the divisiveness on this little sphere as we go spinning around the sun and how futile those divisions are in the scheme of things. So, that seemed like a good starting point. I had written a bunch of songs for the Doughboys in a garage rock style, and I wanted to try my hand at a few of them.

Usually, what happens in the process of recording a new album is that I start writing new stuff, so this record consists of the more blues-tinged [older] material and recent ones, which tend to be on the melodic pop side. I also dug back into the distant past and laid down two songs that were among the first batch I ever wrote when I was a mere tyke of 17 – the opening cut, “You Can Tell Me,” and one called “Plans.”

Richard X. Heyman. Courtesy of Nancy Leigh.

There’s a sub-theme of a musical travelog, with lyrics about various locations on the planet – “Washington Rock,” which is a historical vista near my hometown of Plainfield, New Jersey; “2nd Street” (the one in New York City), which deals with the seedier side of city life; “High Line Scenes,” which depicts a day strolling on that scenic elevated pathway; “Misspent Youth,” an homage to sojourns into the Village to witness some incredible live concerts. And finally, “67,000 Miles An Hour,” where I take on the whole f*cking solar system!

AD: How would you say this album compares to your previous record, Copious Notes?

RXH: With the inclusion of six grittier tracks, the album has a bit more of an edge. Though, as I mentioned before, there’s plenty of harmonic material to balance it out.

AD: From a songwriting perspective, how have your collective experiences shaped your music?

RXH: I can only hope, as I get older, that I have acquired some insights into what the hell is going on, and if I’m lucky, a little wisdom has seeped into my thick skull. Fortunately, I’ve been happily married for many years, but all that happiness doesn’t lend itself to songwriting. That’s not to say I haven’t written my share of love and lust songs for my wife! But for songs involving lost love or heartache, I delve back to my wild oats days when romantic relations went awry. Of course, it’s hard to avoid the insanity that’s swirling all around in the current climate, and I’m sure some of that is sneaking into my writing, though hopefully subtly.

AD: How about the production and mixing side of things? Take me through that process and how the final sounds were honed in.

RXH: Each song starts with a drum performance. We book a studio here in the city (EastSide Sound), where I lay down a couple of dozen songs on a four-piece Rogers kit. Then we bring it all back home and load it into Logic [music software]. Usually, a piano or rhythm guitar comes next, after which I start recording my vocals. I like to get all the singing parts done early in the production. We have an old Russian tube microphone that retains warmth through the digital process. An array of guitars and/or keyboards [will] fill out the track.

Coming up in the age of analog recording, some old habits die hard. All the guitars are recorded through a Fender Vibro Champ amp. The bass, mostly played by [my wife] Nancy these days, follows, and finally, whatever percussion we want, such as bongos, tambourine, shaker, or more exotic instruments like timbales, vibraphone, or congas. A few of the tracks feature brass and strings, which are all played by real human beings, in this case, Probyn Gregory on trombone, trumpet, French horn, and flugelhorn, Julia Kent on cello, and Chris Jenkins on viola.

Richard X. Heyman and Nancy Leigh. Courtesy of Jan Meiselman Lawit.

Nancy and I put together a rough mix of each song and send it and the multi-tracks down to our gifted and trusted mixing engineer, Tony Lewis, who [then] works his magic. When all parties are satisfied, we move on to the next song.

AD: Are you a storyteller, or do you write from personal experience?

RXH: A little bit of both. For example, “Misspent Youth” recounts recollections through rose-colored glasses of going into the Village from New Jersey to see the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Procol Harum, the Who, and one of my personal favorites, the Youngbloods. But then, I never was a traveling salesman (though I did once have a job driving an ice cream truck). So, that song, “Traveling Salesman,” is a little storytelling mixed in with personal memories of people coming to my childhood home, attempting to sell everything from encyclopedias to vacuum cleaners! And let’s not forget the Avon lady and the Fuller Brush man.

AD: Will the material get any time on the live circuit?

RXH: I haven’t any plans for live dates, though you never know. But for now, I’m anxious for people to hear this album, and I always appreciate getting some feedback from listeners as well as the music media.

AD: Last one. What’s next for you?

RXH: I’m in a one-day-at-a-time mode, thankful for being in decent health, having a loving wife and good friends, and still having the wherewithal to put out new music when the muse is in my vicinity.

Header image courtesy of Nancy Leigh.

0 comments