In Part One (Issue 146), we covered the fundamentals of what Roon is and how it works, and the advantages it provides in organizing and accessing digital music. Part Two explores the particulars for getting the best out of a Roon-based audio system.

Where to Put Roon

For full functionality, Roon requires internet access and a robust LAN (local area network). Roon is not a computer audio system; it’s a network audio system. As such, Roon’s capabilities are limited outside of the home. It’s not the solution you would turn to for car audio, background music while traveling or tunes at the workplace. Although Roon Labs has plans to add support for remote access, for now, Roon belongs at your primary residence.

A complete Roon installation comprises multiple devices connected to a single LAN. Central to this installation is a software component Roon Labs calls Core, the coordination point for all other devices. Each Roon subscription is associated with precisely one Core. A Roon system often has multiple Outputs and Controls. Outputs are audio components with a LAN connection that enables Core to stream music to them. Controls are the software applications you and your family use to interact with Roon. Roon Labs offers free Roon Remote apps for Android and iOS and the Roon desktop app for macOS and Microsoft Windows.

Roon provides two different pieces of software that can serve as the Core for your installation: Roon desktop and Roon Server. The desktop app has an all-in-one mode, providing Core, Output, and Control. While this is handy for a quick evaluation or demo of Roon’s features, permanent installations should always separate these functions onto dedicated networked devices for best performance.

Roon Server is the preferred software to use for Core. Roon Labs recommends an Intel Core i3 or better CPU and 4 to 8 GB of RAM. The operating system and Roon Server must be installed on an SSD (Solid State Drive) because accessing Roon’s database requires lots of non-sequential disk access. A mechanical hard disk can’t keep up. Roon Labs provides builds for later macOS and Windows releases, Linux, and QNAP and Synology NAS (Network Attached Storage) devices.

While you can install Roon Server on any system that satisfies the minimum requirements, Roon Labs also offers Roon OS, a highly optimized solution for running Roon Server. Roon OS provides the best experience by far. But, it is only formally supported by Roon Labs on a particular kind of computer called the Intel NUC (Next Unit of Computing). Furthermore, only specific NUC model numbers are supported.

To simplify things for Roon subscribers, Roon Labs offers the Nucleus and Nucleus+ servers, based on Intel Core i3 and i7 NUCs, respectively. These come pre-loaded with Roon OS and offer integration with Control4 smart home automation systems. The only downside to Nucleus/Nucleus+ is their relatively high cost: $1,459 for Nucleus and $2,559 for Nucleus+. These prices do not include an optional internal SATA SSD for music storage. However, although they may seem expensive, Nucleus/Nucleus+ offers good value for money for those who desire a beautiful turnkey solution or require Control4 integration.

For those with experience assembling computer hardware, Roon Labs offers a DIY option to run Roon OS that they call ROCK, or Roon Optimized Core Kit. The online Roon help pages provide detailed instructions covering what parts to buy, assembly, BIOS settings, and Roon OS installation. Doing a ROCK build requires access to a second computer, a USB thumb drive, a small Phillips-head screwdriver, and a bit of patience. Apart from cosmetic differences and no Control4 integration, a ROCK build provides an equivalent experience to Nucleus/Nucleus+.

Finally, a few third parties offer servers that can function as your Roon Core. Typically, these run Roon Server alongside a range of other software, providing functionality that you may or may not need. When considering these solutions, be aware that features outside the Roon ecosystem may not interoperate with your other Roon devices, adding potentially needless complexity to your network audio system.

In summary, Roon is a network audio system for your home. Core is your music mainframe, and Control apps are terminals to interact with and play your music to one or more Output zones. Core, Control, and Outputs communicate over your home LAN, a critical part of any Roon system.

How to Deploy Roon Right

Roon’s vision from the beginning has been, “Roon Plays with Everything.” While not fully realized, Roon Labs has been getting closer, announcing new partnerships and integrations every month or so. As a result, there are countless ways to go about building a Roon system. It could take years for you to explore a large enough cross-section of the available options to identify the best fit for your needs and expectations. I’m hoping that what you learn from this article will save you much of that time, but I’m coming at this from a disadvantaged perspective; I don’t actually know your requirements! There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, but I will provide generally applicable guidance and share specific examples along the way. Armed with this information, you should be able to deploy a Roon system in your home that amazes and delights you and your family.

The Network is the Computer®

Now a registered trademark of Cloudflare, this phrase was first coined in 1984 by John Gage of Sun Microsystems. This network-centric thinking applies equally to a reliable and performant Roon deployment: call it, The Network is the Audio System. After reading over 37,000 posts on Roon Community, I’ve concluded that home LAN issues are the root cause of most Roon performance issues. My advice is to think of your LAN as a component in your audio systems and invest appropriately.

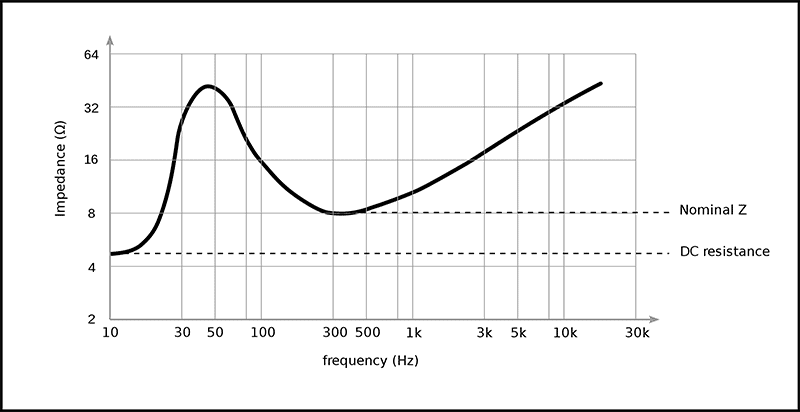

I’m not saying that you have to spend $1,000 on the latest audiophile switch or linear power supply for your router in order to obtain reliability and satisfying sound quality. But, you need to put more thought into how your home network is set up than you did before Roon, to get the best results. Core, high-performance Outputs, and network-attached storage for music files require a wired Ethernet connection to function reliably. One of the reasons for this is that, unlike DLNA (Digital Living Network Alliance) and most other streaming protocols, Roon Core sends uncompressed audio to your Output zones. This minimizes processing on Output devices, but requires more bandwidth and lower latency.

In the US, it’s common for internet service providers (ISPs such as AT&T and Comcast) to provide a Wi-Fi router that also has three or four Ethernet switch ports. This probably won’t be enough for your network audio system. The quality of this “free” internal switch is also questionable, so one of the first components that you should acquire for your Roon deployment is a good Ethernet switch. Select a unit with more ports than you think you’ll need. Unless you have significant experience in managing network devices, stick with a simple, unmanaged switch like the Netgear ProSafe GS116, which requires no user configuration and sells for around $80. Connect one port to your ISP’s router and use the others for Core, Outputs, your NAS, and any other devices that support a wired connection. If you have a separate Wi-Fi router, connect this switch to that instead. This simple network topology will provide years of reliable service with minimum fuss.

While many houses and apartments are prewired with CATV (Cable TV) jacks, few have wired Ethernet jacks positioned at every location where you’d like to set up an audio system. If you own your home or rent from an understanding landlord, this can easily be solved. Hire a low-voltage wiring specialist (e.g., alarm and security camera installers, CATV installers, or home theater integrators). Ask them to pull in-wall networking runs from your switch to each location where you wish to have a Roon Output that supports high-resolution formats. Expect to pay around $150 per run, give or take, depending on location. This may sound expensive, but I promise it will be among the best audio investments you’ll ever make.

Suppose your landlord does not allow you to install in-wall wiring. In that case, a modern Wi-Fi 6 mesh network, like the Netgear Orbi, TP-Link Deco, or Asus ZenWiFi may provide acceptable results. Avoid solutions with fewer than two wired Ethernet ports per node as you’ll need those to connect wired devices, like Core and Outputs. The difference between a mesh network and traditional Wi-Fi extenders is that the nodes use a dedicated high-speed Wi-Fi 6 backhaul connection. Wi-Fi 6 supports close to wired network speeds; however, latency is higher.

Another option for those unable to run wired Ethernet to their audio systems is MoCA 2.5. This technology leverages existing (and often unused) CATV jacks to form a wired network. It’s expensive, more complicated to set up, and latency is about 10 times higher than wired Ethernet. Still, if you happen to have CATV jacks near your equipment, it’s better than Wi-Fi and may outperform mesh solutions if you have a large home.

Powerline networking (which uses a home’s AC electrical wiring to carry data), Wi-Fi extenders, and Wi-Fi, in general, may be satisfactory for other networked home appliances and applications. However, they rarely provide a good experience with Roon. You will never regret installing wired Ethernet runs where that’s possible. Although performance and reliability are inferior to wired Ethernet, MoCA 2.5 and Wi-Fi 6 mesh networks, when properly implemented, are adequate for Roon to function reliably. Invest in your home network as you would any other part of your audio system. You’ll be rewarded with more listening time because you’ll spend less time troubleshooting!

Your Music Mainframe

As mentioned before, each Roon subscription is associated with one Core. The association is formed by logging in to Core using the Control app. Avoid using the computer that runs Core as an Output when sound quality is a priority. Roon Core is an unapologetic CPU hog. The resulting elevated RFI, EMI, fan noise, and ground-plane contamination make such a setup inhospitable for a downstream DAC. The ideal deployment has only two cables connected to the computer running Core: power and Ethernet. No display, keyboard, mouse, and, especially, no DAC. Despite its beautiful casework, Nucleus is not an audio component. It’s a server appliance and should be treated like one.

The best software to use for Core is Roon Server. This application has no user interface, making it ideal for running on an appliance, like Roon’s own Nucleus/Nucleus+ or their DIY ROCK solution. You can also run Roon Server in the background on any PC, Mac, or Linux computer that meets the hardware requirements. However, Roon OS on the Intel NUC platform offers the best experience. Don’t waste time as I did. Buy a Nucleus or build a ROCK system (it’s easier than you think). If Nucleus is too expensive and you’re not comfortable assembling a NUC for ROCK, find someone to build one for you. If you can’t, let me know, and I’ll help.

Plan for a wired Ethernet connection to Core. Physically, the best place for Core is next to your router or that Ethernet switch I recommended. Because the only user interface on the Nucleus or ROCK is a power button, you won’t need a keyboard, mouse, or display. Connect the power and Ethernet, and you’re good to go.

Regarding power, Core must be powered on for you to use your network audio system, because everything flows through it. You may be concerned about operating costs, but let me assure you they are minimal. My 7th gen i5 NUC draws about 10 watts. If I left it running 24/7, monthly power consumption would only be 7.3 kWh. Even with California’s exorbitant prices for electrical power, this works out to $2.70 per month or $32.50/year. Of course, it’s good to conserve electrical energy, and doing so is simple. Just press the power button at the end of your last listening session, and the NUC will gracefully shut down in seconds. Another press in the morning, and you’ll be up and running nearly as fast since Roon OS boots very quickly.

Sound quality should not be a consideration when selecting a device to run Core. When all Outputs are connected via your home LAN and Core is located away from your listening room, all solutions sound precisely the same. Don’t let anyone, especially manufacturers, tell you otherwise. While they all sound the same, they do not provide the same experience. The more complex the operating system upon which Roon Server is run, the more downtime you’ll experience for updates, reboots, maintenance, and troubleshooting. The operating system also competes with Roon Server for hardware resources, impacting responsiveness and even reliability. Roon Server is a minimal operating system that Roon Labs built from the ground up to provide a stable and highly optimized platform for running Roon Server. This is why Roon OS offers the best and most appliance-like experience.

Network Audio Components

If you’ve followed my advice so far, you won’t have a powerful computer spewing RFI and EMI into your audio rack or listening environment. Core is located elsewhere, so you now need audio components to bridge your home LAN and audio systems. Roon Labs aims to support all network audio devices, but not all devices are supported equally. For zones that you use for background music, Apple AirPlay, Google Chromecast, and SONOS protocols will be fine. However, for zones where you do serious listening, you’ll want to be a bit more choosy.

Roon’s own R.A.A.T. (Roon Advanced Audio Transport) streaming protocol offers the best quality and performance in a Roon system. “Roon Ready” certified devices use this protocol effectively, providing responsive playback controls and enhanced feedback in the Roon Control apps. Unfortunately, some manufacturers have been announcing “Roon Ready” certification prematurely. Always check the Roon Partners page before buying. You will also see “Roon Tested” devices on this page. Many of these components are not network-enabled, like USB DACs. Others offer network audio functionality using protocols other than R.A.A.T. Avoid the latter for your primary systems since they will have limited capabilities and format support.

The range of network audio components is broad, but all can be described by their inputs and outputs. Inputs include mediums and protocols. For reliability, wired Ethernet (or fiber) is the preferred medium for Roon, but Wi-Fi sometimes works well enough. Roon does not support Bluetooth. Input protocols include R.A.A.T., AirPlay, Chromecast, SONOS, and others. Outputs can be USB and S/PDIF to feed an external DAC. Some devices also offer analog outputs or amplified outputs to drive passive loudspeakers. A few are networked active speakers with Roon support baked in, like the KEF LS50 Wireless II.

Which type you choose depends on your existing system and requirements. As with any audio component, the more integrated functions a device has, the less flexible it will be when it’s time to upgrade. If you have a DAC that you like, a simple network audio transport, like the ZEN Stream from iFi Audio or the Allo USBridge Signature Player, can be a good option. If you later find a DAC that you like better, you can replace it and use the same transport. The reverse is also true. However, like the SONOS Five, all-in-one components are ideal for background music and easier to move around. These are just a few examples; new products are announced regularly on the Roon Blog.

Controls – There’s an App for That

You almost certainly won’t have to purchase a new device as the Control surface for interacting with Roon. Most reasonably current smartphones, tablets, laptops, and desktop computers can function as Controls. For Android and iOS tablets and smartphones, install the free Roon Remote app via the app store for your device. Download and install the Roon desktop app directly from roonlabs.com on each of your computers that run Microsoft Windows or Apple macOS. I encourage you to install the Roon Control apps on every compatible device you own so that everyone has convenient access to music in the home.

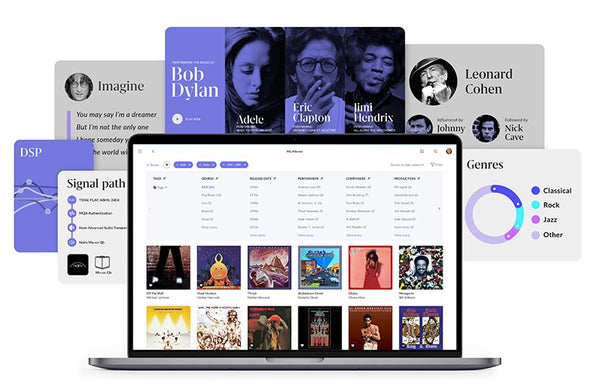

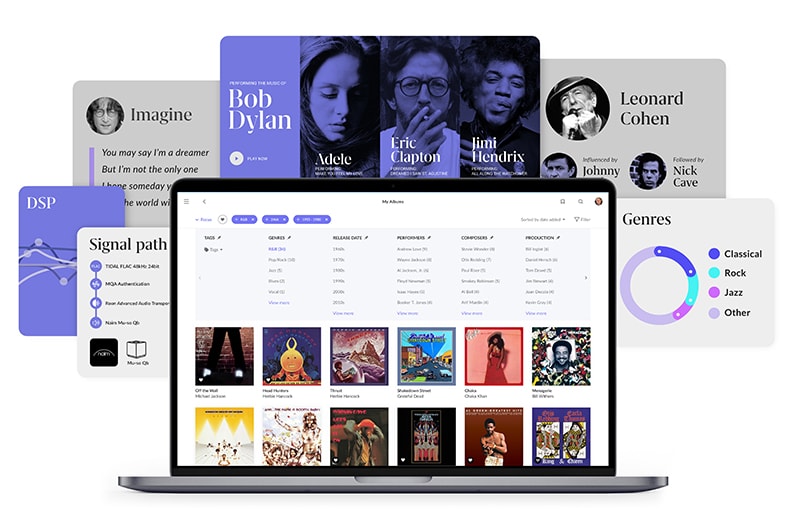

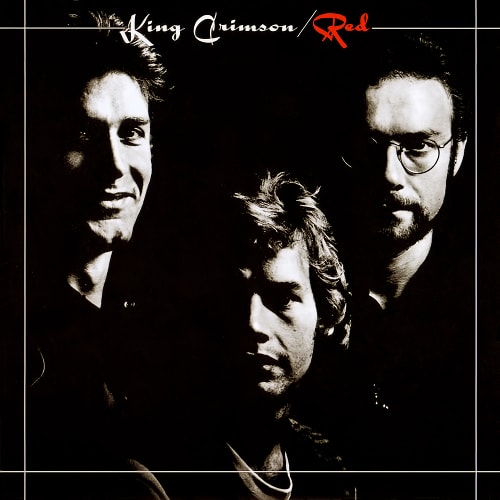

The Roon app on various devices.

While Core and Outputs work best with a wired network connection, Controls almost always use Wi-Fi. It’s essential to ensure that the wired and wireless devices that make up your Roon system are all on the same network. The device discovery protocols that Roon uses do not work well on segmented networks. If you use separate Wi-Fi access points, they should be configured to function as bridges to your wired LAN. You can verify this by reviewing the IP addresses assigned to Core, Outputs, and Controls. The common format of an IP address is four numbers, separated by periods. By default, the first three numbers represent the network address. These three numbers must be identical for every device in your Roon deployment. Core will have trouble discovering and communicating with any device that has a different network address. How to display IP addresses varies, so consult your product documentation or do a Google search if you’re unsure where to look.

You’ll mainly use Roon’s desktop app or Roon Remote to control playback; however, Roon Labs also supports third-party extensions. One of particular note is rooDial, a product offered by Dr. Carl-Werner Oehlrich for a modest fee. This solution enables a Microsoft Surface Dial to function as a physical volume knob for Roon. Press on the top of the dial for play/pause and skip functions. Picking up a tablet to pause, skip a track, or adjust the volume is an unwelcome distraction from that blissful semiconscious state associated with long listening sessions. In contrast, you can operate rooDial without opening your eyes, so nothing takes you out of the music. I regard rooDial or one of Dr. Oehlrich’s other control extensions as an essential part of the Roon experience for serious listeners.

Summary and Resources

Roon is not just another music server or player. It’s an online metadata service and device ecosystem for networked audio in the home. Its search, discovery, and recommendation features make approachable the vast music libraries offered by Qobuz and TIDAL. Expanded and hyperlinked credits, reviews, and bios maximize the pleasure you derive from your existing music library. Roon provides a consistent user interface for playing music on devices with different capabilities. Core and your home LAN are the foundation of your Roon experience. Get these two parts right, and you’ll spend more time enjoying your music.

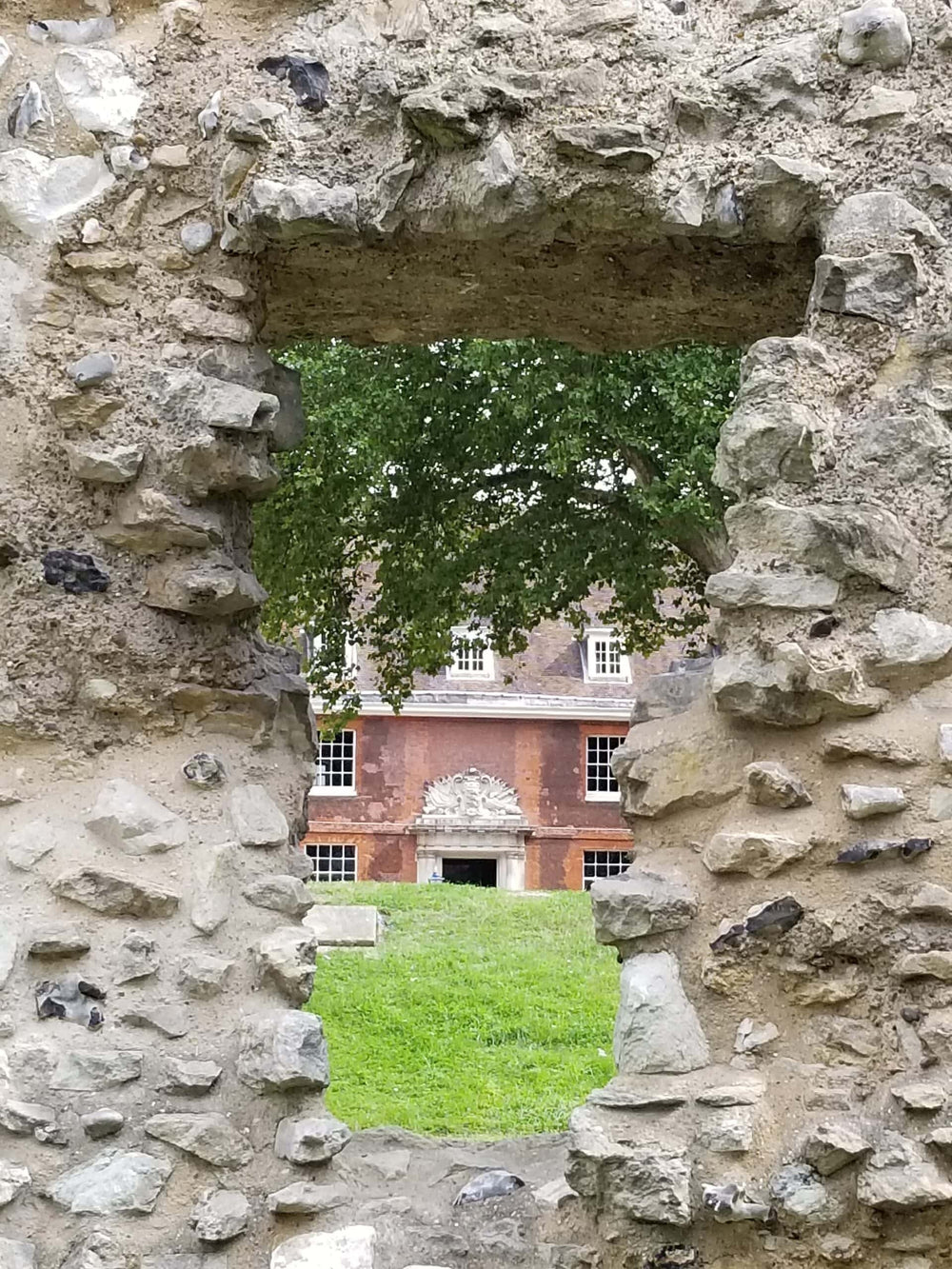

A Microsoft Surface Dial with rooDial volume control software installed.

To learn more about Roon, check out these helpful resources: