Part One of this series on desert island classical music albums appeared in Issue 172. To recap: this list reflects my taste. Yours may be entirely different. In fact, it’s very likely. So, if you hate my choices, I totally understand. But we can still be friends.

My tastes run largely to orchestral music and opera, primarily from the late classical period through to the middle of the 20th century.

Wherever possible, I’ve tried to provide catalog numbers for the recommended recordings. However, since many recordings are available on vinyl, CD, SACD and as downloads, and each format has a different catalog number, it was not always possible. A quick online search should easily find the format you prefer.

I’m going to break this article into multiple parts. Truthfully, if I was stranded on a desert island, I would want to have the entirety of my music collection with me. But this is supposed to be a series about the essential music that I couldn’t live without:

DEBUSSY: Children’s Corner and Other Works. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli; DG

I’m largely indifferent to Debussy’s orchestral music and when it comes to his only opera, Pelleas et Melisande, I’m fond of quoting the late Sir Rudolf Bing who quipped that it was “as long as Götterdämmerung and not as funny.” When it comes to his music for solo piano, however, it’s an entirely different story. It can be playful, introspective, soulful and always moving.

And, without a doubt, the finest exponent of Debussy’s piano music was the eccentric and reclusive but always brilliant Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. Listen to the clarity of the bass ostinati in the opening movement, Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum. I’ve heard lovely performances by other artists, but somehow those notes are always a bit of a blur. Not so on this recording. Every note is crystal clear.

DVORAK: The Symphonies. István Kertész, London Symphony; Decca

In the realm of “what might have been,” we have the late conductor István Kertész who perished in a tragic drowning accident at the age of 43. He was widely sought after by major orchestras and, in his short career, nevertheless managed to create an extensive recording catalog. Many of those recordings are still considered benchmarks, particularly his recording of Bartok’s only opera, Bluebeard’s Castle. His traversal of the Brahms symphonies is also very fine.

But I don’t think anyone has ever quite equaled his cycle of the Dvorak symphonies and tone poems for a deep sympathy with this composer’s great music. Beautifully played by the London Symphony and available as a 96/24 high-resolution download, these are glorious performances. Listen, for example, to the way he makes the scherzo from the Fifth Symphony bounce and dance. And that’s just one example from a cycle full of wonderful moments.

GERSHWIN: An American in Paris (and other works), James Levine, Chicago Symphony; DG

It’s inarguable that George Gershwin was a genius, one who left an indelible mark on American music even if he died far too young. As a chorister, I had the opportunity to be part of a performance of Porgy and Bess. It was the most fun I’d had (musically) in a long time. And frankly, I could pick a number of Gershwin’s “classical” pieces, but I’ve always had a special love for An American in Paris; maybe it was the movie.

I listened to quite a number of recordings of this work from a wide array of American conductors including Leonard Bernstein, Michel Tilson Thomas, André Previn (ok, fine, he was born in Berlin, but still…), Leonard Slatkin and Lorin Maazel (ironically, an American who was born in Paris). None of them has quite the swagger of this recording, made in 1990. You can almost picture an arrogant young American, strolling the boulevards of Paris in the innocent days between the World Wars. The playing of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is brilliant, at times brash (appropriate for this music) but highly effective, and the recording quality is excellent.

HANDEL: Messiah. Sir Neville Marriner, Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Elly Ameling, Anna Reynolds, Philip Langridge, Gwynne Howell; Decca

As a long-time chorister, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve sung in this oratorio. I think I could sing many of the choruses in my sleep. I’ve even recorded it once (with Sir Andrew Davis and the Toronto Symphony on Chandos) and, of course, I have listened to countless recordings.

This is the one I keep coming back to. While Marriner uses modern instruments and tuning, nevertheless there is, throughout, a sense of “rightness” in tempo, in rhythm, in dynamics in every chorus and aria. Just as important, there is a real feeling of joy in this performance. It never once feels perfunctory or routine. And, of course, the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields plays with their usual flawless elan.

MAHLER: Des Knaben Wunderhorn. London Symphony, George Szell, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; Warner Classics

Mahler was, in his day, a widely renowned opera conductor, holding music director posts at both the Vienna State Opera and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. In the course of a lengthy interview, Otto Klemperer – who was a protégé – remarked that “People talk of the greatness of Toscanini, but Mahler was much greater.” Strangely, however, despite his significant output as a composer, Mahler wrote no operas. What he did write, however, were several wonderful song cycles for soloists and orchestra and, of those, this one is my personal favorite. At times cheeky and irreverent and at other times lugubrious and mournful, the music is brilliantly colorful.

This recording, from 1968, has both soloists at the top of their form with an always sympathetic accompaniment by George Szell, leading the London Symphony. I’ve heard numerous performances of this cycle including a wonderful live performance featuring Jessye Norman and John Shirley-Quirk. However, this trio seems to somehow capture the spirit of the cycle better than any more contemporary recording.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 6. Pierre Boulez, Vienna Philharmonic; DG

I’m a huge fan of Mahler and I own many complete recordings of his symphonies. If I were stranded on a desert island, I would not want to be without his music. While I love all of them, as it happens, my two favorites are the Symphony No. 6 and No. 7. Not a usual choice, I realize. Most people would probably opt for No. 2 – the Resurrection Symphony or perhaps No. 8, the so-called “Symphony of a Thousand.” Yet something about these two symphonies speaks to me in a very special way.

I recently listened to sections of 20 different recordings of the Sixth Symphony and while there are many lovely interpretations, this is the one that felt the most true to my vision of Mahler’s intentions. It is clear, unsentimental, and beautifully played, with Boulez’ usual attention to transparency and detail. Some may find the first movement a bit on the slow side, but the third movement Andante Moderato is played with such gorgeous intensity that it sweeps away any second thoughts.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 7. Michael Tilson Thomas, San Francisco Symphony; SFS Media

One could be forgiven for thinking that Mahler conceived this work as a concerto for timpani and orchestra. The percussion plays a major role in this symphony, as in his Sixth, and the timpani is particularly prominent in the Second, Third and Fifth movements. But, of course, there’s a lot more to this, Mahler’s most iconoclastic symphony, than just percussion.

And there are many great recordings, including Otto Klemperer’s equally distinctive recording on EMI (far and away the slowest on record, but gorgeously played), Leonard Bernstein with the New York Philharmonic (recorded twice, once on Sony and the other on DG), Riccardo Chailly with the Concertgebouw, a beautifully detailed and recorded performance by Eliahu Inbal and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, James Levine with the Chicago Symphony (wonderful recording of the percussion) and several recordings by Bernard Haitink.

Michael Tilson Thomas has a great affinity for Mahler and particularly for this symphony. Listen, for example, to the third movement Scherzo, marked Schattenhaft (shadowy). MTT manages to bring out the eeriness of this movement and thus render it truly shadowy. In addition, this performance benefits from a beautiful, clear recording, especially in the 96/24 high-resolution version.

MOZART: Late Symphonies. René Jacobs, Freiburger Barockorchester; Harmonia Mundi HMC901959 and HMC901958

René Jacobs began his musical career as a countertenor but in the late ’70s he turned his attention to conducting, working with a number of European period-instrument orchestras. He has recorded music ranging from Monteverdi to Bach to Schubert but is justly renowned for his recordings of Mozart operas, which are multiple award winners. These recordings of the last four Mozart symphonies are equally attractive. The playing is energetic, sparkling and always engaging, and the smaller forces ensure that all of Mozart’s contrapuntal lines are clearly audible. He takes all (or most) of the repeats and the recording quality is excellent.

MOZART: Die Zauberflöte. Otto Klemperer, Philharmonia, Nicolai Gedda, Walter Berry, Gundula Janowitz, Lucia Popp, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Christa Ludwig, Gerhard Unger, et al; Warner Classics

I love all of Mozart’s late operas (with the possible exception of La Clemenza di Tito which can get a bit tedious). But I have a special place in my heart for this, possibly the most charming of them all. A quick online search yields at least 30 different recordings, and well over a dozen videos of the opera. I have nine different recordings in my collection.

Recorded without dialogue, but with a luxury cast (including Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Christa Ludwig and Marga Hoffgen as the three ladies), it benefits from Klemperer’s sure hand and obvious love for the work. There are other wonderful recordings including those by René Jacobs on period instruments and with extensive dialogue. I’m also very fond of Solti’s first recording with the Vienna Philharmonic from 1969. But Klemperer’s performance, recorded in 1964 after a run of performances at Covent Garden (with Joan Sutherland as the Queen of the Night), remains the one that I return to, time and again.

ORFF: Carmina Burana. James Levine, Chicago Symphony; DG

As a chorister, this is another piece that I have performed many times under a variety of conductors. I know that some of it has become a cliche, frequently used in television commercials to hawk a variety of mundane products. But it is nevertheless a very carefully crafted piece of music and – as a personal aside – very entertaining, both as a participant and as an audience member.

As with Handel’s Messiah (above), I’ve listened to many, many recordings of this work and many of them are excellent, in particular the famous Eugen Jochum performance on DG with the forces of the Deutsche Oper Berlin and three of the greatest soloists imaginable. But the performance above, in my opinion, manages to eclipse even that one. Perhaps the soloists are not quite in the same league as Gundula Janowitz, Gerhard Stolze and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, but the playing of the Chicago Symphony is crisper and better-controlled, the singing of the choruses is clearer and the recording quality is far better.

PROKOFIEV: Romeo and Juliet. Lorin Maazel, Cleveland Orchestra; Decca

I used to regularly accompany my mother to performances of the National Ballet of Canada and this is where I first heard Prokofiev’s sparkling score for Romeo and Juliet. It was love at first listen. I’ve heard many performances of this lengthy ballet, but none of them has resonated with me as much as this one, recorded relatively early in Lorin Maazel’s tenure with the Cleveland Orchestra. Maazel has sometimes been criticized as cool and analytical, but in this performance, I don’t hear that at all. It’s certainly not a “heart on the sleeves” performance, but I don’t think that Prokofiev’s music particularly lends itself to that approach. What I hear is extremely fine playing by one of America’s great orchestras, sharp, rhythmic clarity, and sensitivity to the widely varying moods of the ballet.

PROKOFIEV: Symphonies No. 1 and No. 5. James Levine, Chicago Symphony; DG

Combined on a single disc, these are fine performances of Prokofiev’s two best-known symphonies. Truth to tell, there are better performances of the First (“Classical”) Symphony (for example, Sir Neville Marriner with the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields), but this is a particularly good recording of the Fifth Symphony played by the Chicago Symphony during the era when conducting duties were shared between Sir Georg Solti and James Levine and the CSO was considered the finest orchestra in America. Levine manages to capture the sharpness and angularity of Prokofiev’s motoric rhythms, and DG’s recording is clear and transparent.

PUCCINI: La Boheme. Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, Luciano Pavarotti, Mirella Freni, Nikolai Ghiaurov, et al; Decca

I have very mixed feelings about the late Herbert von Karajan. It’s inarguable that he took an already fine orchestra – the Berlin Philharmonic – and built it into one of the world’s greatest ensembles. But he was also a bald-faced political opportunist and later in his conducting career, self-indulgent in the extreme; at least to my ears.

That said, his recordings of Puccini are wonderful. Frankly, I prefer the “shabby little shocker” Tosca to La Boheme, which I find a bit maudlin. But this recording is so very wonderful that it simply cannot be ignored or missed. Luciano Pavarotti’s silver voice cuts through the orchestral textures like the proverbial hot knife through butter, and the rest of the cast is almost as fine. Karajan provides a sensitive, detailed accompaniment and I can think of no performance of this opera that quite equals this one.

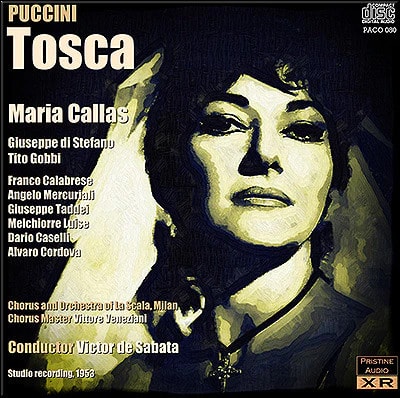

PUCCINI: Tosca. Victor de Sabata, La Scala, Maria Callas, Giuseppe di Stefano, Tito Gobbi (1953); Pristine Classical PACO080

Based on a play by the French playwright Victorien Sardou, this “shabby little shocker” – as one contemporary critic described it – might, perhaps, have shocked the sensibilities of the late 19th century audience at its premiere. But it has consistently been one of the most popular of Puccini’s operas and, indeed, one of the most popular operas in the standard repertoire.

There are many great recordings of this opera. To mention a couple: Herbert von Karajan with the Vienna Philharmonic, Leontyne Price, di Stefano and Taddei; Lorin Maazel with the Academia Santa Cecilia, Birgit Nilsson, Corelli and Fischer-Dieskau. Of course, there are many more.

But the recording above is undoubtedly the gold standard. Maria Callas is Floria Tosca and Tito Gobbi was the most renowned Scarpia of the 20th century. Victor de Sabata conducts an entirely idiomatic performance with the forces of La Scala. If there’s any criticism, it is that the recording is rather closely miked, particularly the orchestra. But Pristine Classical has performed a remarkable restoration of this recording, rendering it almost modern and therefore even more relevant.

0 comments