My experiences with Black Sabbath go all the way back to my pre-teen years, and most of their classic music has been ingrained into my psyche throughout most of my lifetime. However, to be honest, at the point when Ozzy departed the band, my musical interests had diversified to the point where I pretty much missed Sabbath’s second act at the time it happened. Deluxe Editions of Heaven and Hell and Mob Rules, the first two studio releases from that incarnation of Black Sabbath, have just been released, and I thought it would be interesting to take another listen to the Ronnie James Dio-fronted version of Sabbath. I hope you don’t mind my sharing a bit of a reminisce about the band…

My first exposure to Black Sabbath came at a pretty early age. My next door neighbor Stanley Wilson was a fairly troubled youth — and his parents each had their own problems — so they both tried to overcompensate by indulging his every whim. He had a fairly sophisticated (for 1970) record player, and his parents would purchase whatever current release LPs he desired, no questions asked. We’d sit on his front porch and play Black Sabbath and Master of Reality virtually non-stop, and usually much to the chagrin of the crabby old man who lived across the street. The old guy hobbled around with a cane, and was barely mobile; I guess his lack of mobility held him back from coming over and making much of a fuss about the noise.

Until this beautiful warm day in September, 1970, when Stanley had just gotten home from the store with a just-released copy of Sabbath’s new album, Paranoid. I rushed over, and we started cranking it — at least as loudly as the GE record player would crank! “Iron Man” had just kicked in, when suddenly, the old codger had taken all he could apparently stand, lunged to his feet, and proceeded to hobble down the street — to my house, where he proceeded to pound on the front door with his cane. My mom answered the door; about that time, I told Stanley to nudge the volume down so we could hear what was about to transpire. “Pauline!” the old man shouted, “I want you to get over there RIGHT NOW and tell those gosh-darn kids to turn that gosh-darn noise down, NOW!”

My mom was fairly old-school, fairly conservative, and very religious, and I expected the absolute worst — but at that moment, she shocked me in a way she never matched for the remainder of her life. She raised her voice — which she very rarely ever did — and told the old guy to go home, and leave those kids alone, they’re just playing some records, and are not bothering anyone! He hobbled back to his house, grumbling the whole way, going inside and slamming the door behind him. I wanted to jump up and scream, “RIGHT ON, MOM!” but my enthusiasm was short-lived; my mom immediately came next door, looked us sternly in the eye, and told us to “turn that rock and roll down, now!”

As I entered my teen years, the rock and roll didn’t stay turned down for very long — it actually got louder and louder, almost deafeningly so. In mid-1978, Steve — my high school best friend — told me he was getting Black Sabbath tickets, and did I want to go; oh, heck yes! It was Sabbath’s tenth anniversary tour, and they’d just released Never Say Die, which was probably their most uneven record yet. But the tour stop at the Omni in Atlanta had Blue Öyster Cult on the bill — another band I’d become completely infatuated with — so, of course, I was definitely in. The show quickly sold out — and not long after getting our tickets, the local rock radio station, 96 Rock (WKLS) announced that for some reason, the tour lineup had been changed, and BOC was off the ticket. Bummer — that is, until they announced that replacing them would be the Ramones and Van Halen!

The day of the show, I drove over to Steve’s place in Athens, Georgia — he was a second-year student at UGA, and we hung out with the handful of friends who were going to the show later that evening. We listened to Sabbath records all day, smoked a few blunts, and chugged a couple beers. All day, Steve kept saying, “you know, Sabbath could be a really great band — if they only had a drummer!” I didn’t particularly agree, but never one to dampen the festive atmosphere, I kept my thoughts to myself.

We had really good seats at the old Omni (it was actually still pretty new then), and were only about ten rows in front of the stage on the floor. The Ramones hit the stage, and I’d never seen anything like it — they played like, fifteen songs in fifteen minutes, with absolutely no conversation in between. Just a really loud “One-two-three-FOUR!!” in between every tune — we laughed and laughed, but really, really dug it. Then Van Halen came out — holy crap, Eddie Van Halen playing “Eruption;” we just about freaked! Dave Lee doing those high leg kicks, jumps and splits — it was incredibly entertaining. Black Sabbath had a tough road ahead of them if they were going to top the Ramones and VH!

Keyboard player Don Airey, who played on the first few Ozzy albums, relates a story that Ozzy told regularly on his first solo tour that revolved around Black Sabbath getting embarrassed on stage by their opening act. The band in question was KISS — still virtually unknown at the time — but Ozzy was totally pissed that KISS’s already great level of showmanship completely outclassed them as the headlining act. And he swore that would never happen again — even if Sabbath had to go out on tour with some California bar band as an opener. On the first night of the 1978 tour, Van Halen was already on stage when Sabbath arrived at the venue, where they were greeted by the opening notes of Eddie’s “Eruption”; Ozzy and Tommy just stared at each other in stunned silence. The crowd went absolutely wild: it had happened again, and after the conclusion of the Sabbath tour, Van Halen had become the headliners.

Anyway, when Black Sabbath hit the stage, we all noticed that there was a circular drum riser with what appeared to be strobe lights all around it. What’s that all about? Sabbath absolutely killed it that night; when the opening bars of “War Pigs” blasted forth, we left our seats and never sat down for the remainder of the show. The new songs from Never Say Die fared much better live and seemed much more essential than the studio versions, and the band’s renditions of all their classic hits were revelatory. When drummer Bill Ward’s solo came, as usual, in the middle of “Rat Salad” (from Paranoid); it started out slowly, with some jazzy drumming at first with a long run-out, then there was a bit of a pause. Ward then tapped a cymbal, and a strobe light flashed; he’d then hit one of the tom-toms, and another strobe would flash, and the riser would rotate a bit. It continued to proceed, with every drumbeat and cymbal stroke, a strobe would flash and the drum riser started spinning…faster…faster…faster! Until the point when it almost felt like it would leave the stage and go spinning into space! I swear, on that night, Bill Ward would have given Neil Peart or Carl Palmer a run for their money — it was without a doubt one of the most impressive drum solos I’ve ever witnessed, bar none. When the cheering finally subsided, I turned to Steve and yelled, “yeah, you’re right, man — they really need a drummer!”

It marked Ozzy’s last tour as an original member of the band; in less than a year, he was fired for excessive drinking and drug use. Which must have been off the chain, since everybody else in the band did their fair share of partying at the time. After Ozzy’s departure, Sharon Arden (soon to be Sharon Osborne) — who was Sabbath manager Don Arden’s daughter — suggested that the band hire former Rainbow lead singer Ronnie James Dio as Ozzy’s replacement. She then helped Ozzy get his sh*t together and launch a successful solo career; for both Ozzy and for Black Sabbath, a new world order had been established. But for all Black Sabbath fans, the change wasn’t a completely welcome one. For me personally, Sabbath just kind of fell off my radar for a while; my only contact with the RJD-fronted Sabbath was the song “Mob Rules” from the Heavy Metal movie and soundtrack.

And that Black Sabbath/Blue Öyster Cult tour did eventually happen; while I didn’t see the tour, Steve and I did go see the film that documented the tour, Black and Blue, at a midnight movie. That experience kind of turned me off from the Ronnie James Dio version of the band; Dio’s on stage personality was charismatic, but — for me, at least — his excessive posturing was kind of off-putting. His on stage presence was a little over the top for me — I definitely fell strongly into the Ozzy as Sabbath’s lead singer camp.

Fast forward to many years later: I was hosting an extended family get-together, and my now-grown kids and I were sitting around the pool having a few beers, talking about music and the like. My oldest stepson Joe had his iPhone, and was playing various music tracks from YouTube, when he suddenly said, “how about this…” and played “The Mob Rules.” My youngest step son Josh lunged towards Joe immediately, demanding that he “turn that crap off!” Joe protested, “but it’s Black Sabbath!” “No,” Josh said sternly. “No Ozzy, not Sabbath!” So I guess not everyone’s entirely keen on the Ronnie James Dio version of Sabbath.

I’ve long since added the studio versions of both Heaven and Hell and Mob Rules to my music library, and have come to develop quite an appreciation for this version of the band and the music. So I thought it would be great to see if the expanded Deluxe Editions offered any real improvements over the originals.

Black Sabbath — Heaven and Hell (Deluxe Edition)

Black Sabbath’s last two albums with Ozzy, Technical Ecstasy (1976) and Never Say Die (1978) weren’t well received critically, though both earned the band gold records for album sales, although it took over twenty years for each album to reach that height. Tensions were already beginning to brew within the band; Tony Iommi was unhappy with his bandmates during the aftermath of the Technical Ecstasy sessions, when they all essentially left him alone to handle the heavy lifting with the record’s production chores. And by the time the band went into the studio for Never Say Die, Ozzy was already toying with leaving the band; he actually split for a very brief time and was replaced by Savoy Brown’s Dave Walker. That didn’t work out, and Ozzy eventually returned, but Never Say Die was definitely the most uneven effort in the band’s history. This made it relatively easy for the band to give Ozzy the axe following the tour, especially in light of all the negative criticism in most music magazines. Guitarist and bandleader Iommi instructed drummer Bill Ward to inform Ozzy of the band’s decision. Ward says that he was drinking a lot, and was drunk at the time, as were the other members of the band most of the time, and he really couldn’t say how Ozzy took the news.

When Ronnie James Dio arrived, he breathed new life into the band; his singing style was so very different from that of Ozzy that it freed Iommi and bassist Geezer Butler to alter their styles compositionally, and in a way that gave them increased confidence in the band’s new music. Dio’s arrival wasn’t so matter of fact; Bill Ward and Geezer Butler were actually experimenting with forming a new band, and despite Sharon Arden’s insistence to Iommi that RJD was their man, it took some time before everything came together. The new album, Heaven and Hell, was well received critically, and quickly embraced by Sabbath fans; it raced to No. 28 on the US charts and was certified Platinum (one million units sold) in the year of its release. The album sold well worldwide, and the ensuing tour sold out dates at just about every stop. The reception by fans wasn’t always warm and fuzzy, with audiences chanting, “Ozzy, Ozzy” frequently at venues along the way. This unnerved Ronnie James Dio to no end, but the new version of the band eventually won the fans over. And they played all the classics, although their new music was very different from that of the band during the Ozzy period.

Despite its critical and commercial success, Heaven and Hell flew completely under my radar at the time of its release — I guess I was completely preoccupied with all the crap going on in my life at the time. And probably considered the RJD version of Black Sabbath unworthy of my then especially limited time and dollars. Heaven and Hell (Deluxe Edition) is being made available as both 2-CD and 2-LP sets, along with 24/96 digital streaming on most major services. There are differences between the versions; both the CD and streaming versions feature a first disc with the 2021 remastered original album, and a second disc of studio outtakes and live recordings. Because of the space limitations of the vinyl format, you get the newly remastered album on the first LP, but only a mixture of selections from the bonus studio outtakes and live material on the second LP. Most of the material has been previously released on a 2011 Universal Deluxe Edition, but the four 1981 live tracks from a Hammersmith Odeon date have never seen the light of day. Unfortunately, three of the four live tracks duplicate material already included from the Hartford, Connecticut 1980 tracks, and don’t add a lot in terms of interest to the new set.

https://youtu.be/0BfgGENh8Rw

None of the physical releases were available at the time of my review, so all my listening with Heaven and Hell was done via Qobuz’s 24/96 high-resolution digital files. Probably the main reason to even consider checking out this new Deluxe Edition is because of the improved sound quality. There’s a greater clarity of sound with all the instrumentation, and especially with Ronnie James Dio’s vocals, which were somewhat recessed in the original release. That said, the new remastering is more heavily compressed than the original release, and neither the studio nor live tracks were what I would consider real audiophile quality.

The live tracks from the Hammersmith Odeon concert were much more well-recorded than the Hartford concert, but with me not being a particular disciple of this version of the band, I could easily take them or leave them. And even if I didn’t especially care for watching RJD’s stylings in the Black and Blue concert film back in the day, it would probably be pretty interesting to go back and have another look at the film. Especially after all this time, and besides, I really loved the BÖC segments. The LP version of this set would likely suffer from less compression; even if that’s not part of your plan, true fans will want to at least check out the digital files.

Rhino Records, 2 CD/2 LP (download/streaming from Qobuz [24/96], Tidal, Amazon, Google Play Music, Pandora, Deezer, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube, TuneIn)

Black Sabbath — Mob Rules (Deluxe Edition)

Despite the success of Heaven and Hell and the ensuing tour, drummer Bill Ward had never quite recovered from being the “hit man” when it came to delivering the news to Ozzy Osbourne that the band had fired him. Ward had progressively stepped up his already out-of-control drinking, and unceremoniously quit the band midway through the tour; he made it quite clear that Ozzy was and would always be Black Sabbath’s lead singer. Ward was promptly replaced by session drummer Vinnie Appice, who wouldn’t appear on another Black Sabbath album until 1992’s Dehumanizer. And although there was quite a bit of skepticism and apprehension within the band about Ward’s replacement, apparently Vinnie Appice worshipped Bill Ward, knew all of his signature drum styles, and was a seamless fit with the new lineup.

The genesis of Mob Rules began when Sabbath was contracted to contribute a song for the animated motion picture Heavy Metal. “Mob Rules” was the song that the band created for the soundtrack album, and the tune “E5150” also appeared in the movie, though it didn’t make the eventual cut for the album. The studio sessions for Mob Rules were plagued by creative differences in the band along with a multitude of technical problems; whereas the sessions for Heaven and Hell were fairly easy-going and stressless, the pressure to duplicate that record’s phenomenal success was almost more than the band members could bear. Compounding the situation, Tony Iommi was having a really difficult time getting the guitar sound he was hoping for in the studio. It took a protracted period of time, especially with the title cut, “The Mob Rules,” which apparently went through multiple takes before the band was satisfied with the results. Iommi considered the Heavy Metal version of the song superior in every way, but contractually, it couldn’t be used on the studio album.

Mob Rules debuted to generally mixed criticism and lukewarm commercial success; many of the music mags basically referred to it as Heaven and Hell, Part II, because musically and thematically, the song structures bore a strong resemblance to the previous record. It’s a criticism which Tony Iommi has constantly taken issue with in the ensuing years since Mob Rules was released; he still believes it’s a very good record. The album only went Gold in the US, and experienced similar worldwide sales, and the resulting tour found the band already beginning to splinter. Apparently, Ronnie James Dio had been approached by the record label and offered a solo contract, which didn’t go over well with Iommi or Butler. And there were arguments over a live album, Live Evil, that was being put together during the tour; Dio was unhappy with some of the sound editing, which he didn’t feel flattered his vocals, and he was also particularly unhappy with the album’s design and photography. He felt the photos that featured him were indistinct, and that the photos of the remaining members of the band were too prominent. At the conclusion of the tour, Dio split, taking Appice with him, and formed his own band, Dio, releasing the 1983 album Holy Diver to both critical and commercial acclaim.

As with Heaven and Hell (Deluxe Edition), there are distinct differences in the release versions, depending on your choice of format. One of the definite highlights is the inclusion of the Heavy Metal version of “The Mob Rules,” which makes it perfectly clear why Tony Iommi obsessed with trying to get the same sound for the studio release — it’s obviously superior from the very first note. There are a few studio outtakes, more tracks from the Hammersmith Odeon concert, and the real bonus is a complete 1982 concert from Portland, Oregon, which has never been previously released.

https://youtu.be/mlZj4gMxF7A

As with the Heaven and Hell set, Mob Rules (Deluxe Edition) is also being made available as both a double-CD and double-LP, along with 24/96 digital files streaming on most major services. Again, all my listening was done via Qobuz’s 24/96 high-resolution digital files, and again, the new remastering is definitely more compressed than the original release. Yes, there’s more clarity of sound here — as with Heaven and Hell — but the level of compression makes it difficult to really crank it and enjoy the music. The inclusion of the previously unreleased live tracks from the Portland show will probably make this required listening for true fans and completists, though overall, I found the Deluxe Edition to be something of a mixed bag. YMMV.

Rhino Records, 2 CD/2 LP (download/streaming from Qobuz [24/96], Tidal, Amazon, Google Play Music, Pandora, Deezer, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube, TuneIn)

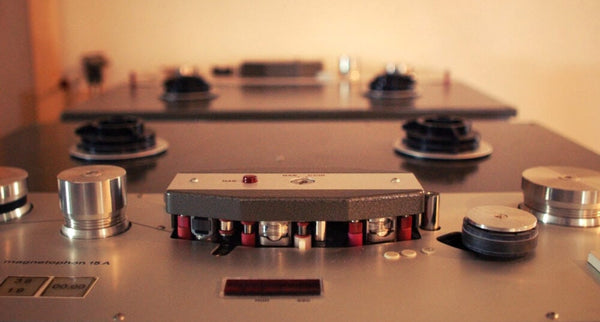

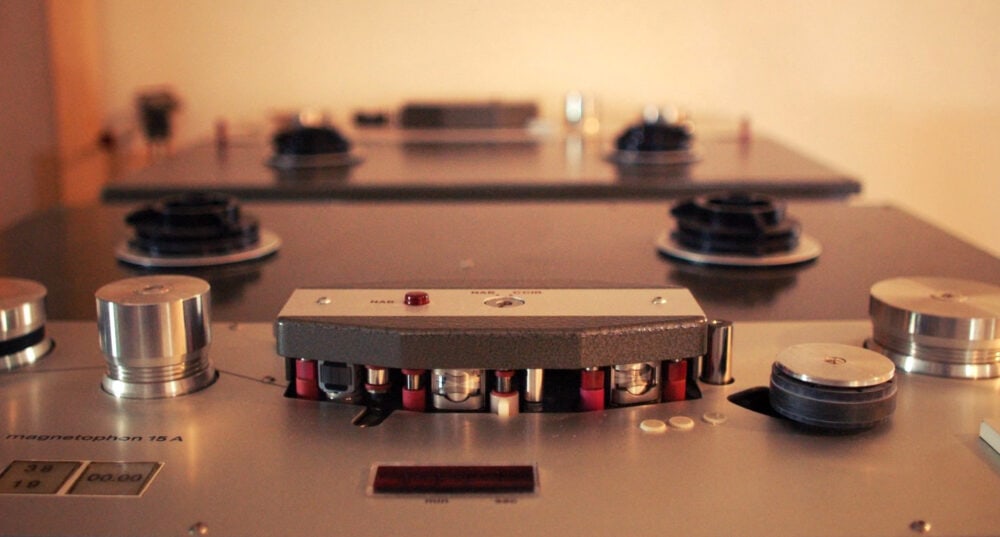

Technics RS 1500 Series.

Technics RS 1500 Series. A Studer J37 tape machine in Abbey Road Studios. Courtesy of Abbey Road Studios.

A Studer J37 tape machine in Abbey Road Studios. Courtesy of Abbey Road Studios.

Featuring a cross-field head for improved high-frequency response! Tandberg 9000X ad, circa 1972. Courtesy of Don Kaplan.

Featuring a cross-field head for improved high-frequency response! Tandberg 9000X ad, circa 1972. Courtesy of Don Kaplan.

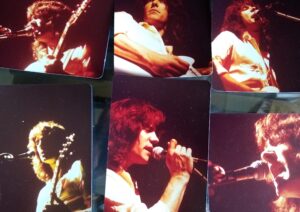

Photos of Roye Albrighton performing. Courtesy of Ken Sander.

Photos of Roye Albrighton performing. Courtesy of Ken Sander. Ken Sander (yellow shirt) and Nektar enjoying a relaxing moment on the road on their first tour in Chicago.

Ken Sander (yellow shirt) and Nektar enjoying a relaxing moment on the road on their first tour in Chicago.

Musical enjoyment is ultimately what it's all about. The

Musical enjoyment is ultimately what it's all about. The

When the speakers sound right, the whole family likes it! Courtesy of

When the speakers sound right, the whole family likes it! Courtesy of

Mount Everest. Courtesy of

Mount Everest. Courtesy of

Tektronix 545B vacuum tube mainframe oscilloscope.

Tektronix 545B vacuum tube mainframe oscilloscope.

The Tektronix mainframe in front of the Hardinge HLV late, in the machine shop, assisting with mechanical measurements.

The Tektronix mainframe in front of the Hardinge HLV late, in the machine shop, assisting with mechanical measurements.

Telefunken M15A tape machines, awaiting installation in the new custom studio furniture.

Telefunken M15A tape machines, awaiting installation in the new custom studio furniture.

One of our disk mastering lathes in action.

One of our disk mastering lathes in action. Our custom-made Thermionic Culture Green Fat Bustard vacuum tube summing mixer.

Our custom-made Thermionic Culture Green Fat Bustard vacuum tube summing mixer.

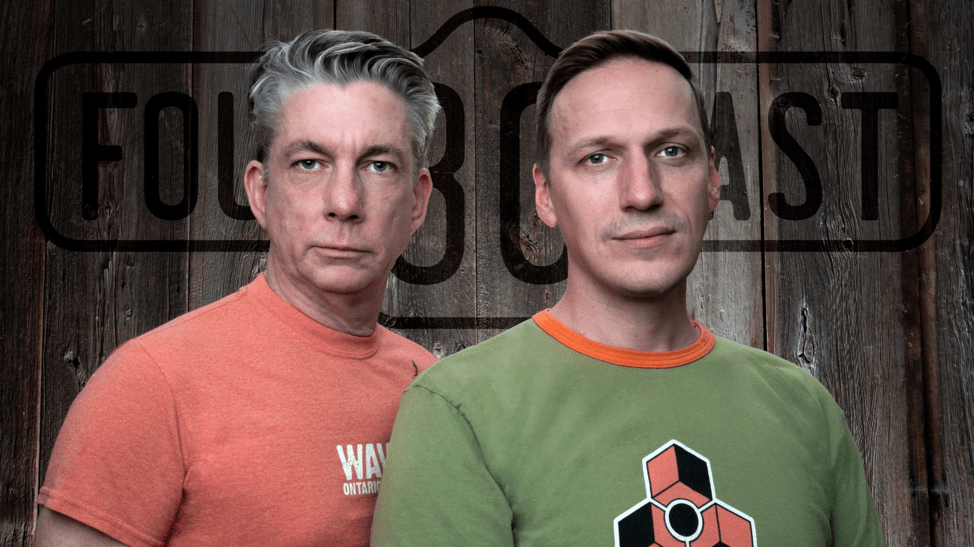

Tony Grace and Rob DeBoer of Four80East.

Tony Grace and Rob DeBoer of Four80East.

6DJ8/ECC88 and 6922 tubes. Will they work?

6DJ8/ECC88 and 6922 tubes. Will they work? Well, one of these is vintage gold. Kenwood KR-710 and Marantz 2216b, author’s collection.

Well, one of these is vintage gold. Kenwood KR-710 and Marantz 2216b, author’s collection. It won't make your system sound better, but you won't have to listen over the sound of your rumbling stomach. Courtesy of

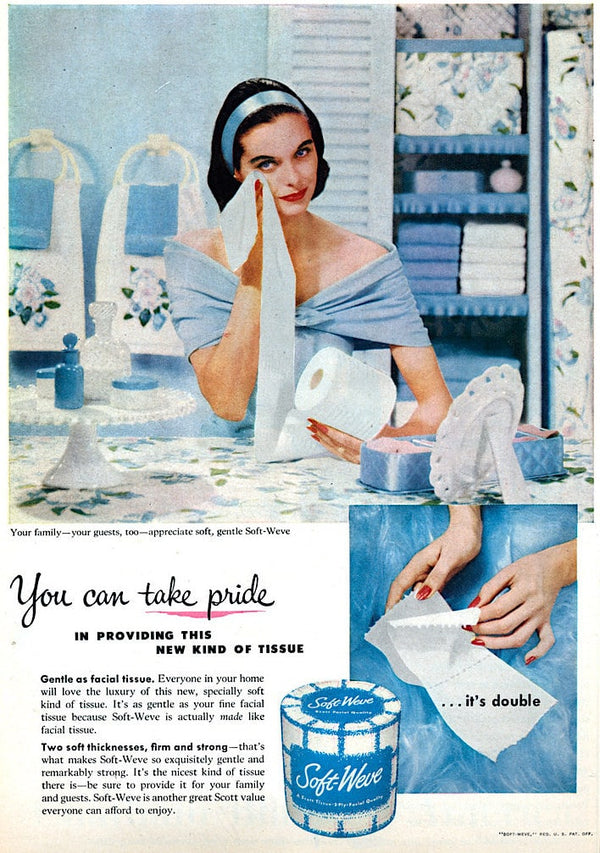

It won't make your system sound better, but you won't have to listen over the sound of your rumbling stomach. Courtesy of

United Recording Studios.

United Recording Studios. Studio B.

Studio B. Studio A.

Studio A. Mixing console, Studio A control room.

Mixing console, Studio A control room. Archiving room at United Recording.

Archiving room at United Recording.