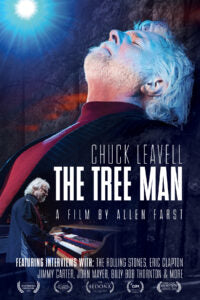

Rock and roll documentaries have become fairly predictable. Over the past year alone I think I must have watched about two dozen. They tend to follow a formula, and if the focus of the film is pretty well-known, it’s likely that you won’t leave the viewing having learned much more than you already knew going in. That’s not the case with Chuck Leavell: The Tree Man. This is the story of the legendary keyboardist, often described as the “Fifth Rolling Stone.” What sets it apart is the manner in which it showcases Leavell’s talent and body of work, and reveals his love of nature, his commitment to family, and his remarkable sense of humanity. There’s a balance to the film that’s rare and ironically metaphoric to how Chuck Leavell leads his life. The film is packed with star power, including interviews with Billy Bob Thornton, Mick Jagger, President Jimmy Carter, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Bonnie Raitt, Dickey Betts, Paul Shaffer, Chris Robinson, Charlie Daniels, Miranda Lambert, Charlie Watts, Bruce Hornsby, Julian Lennon, Mike Mills, John Bell, Pat Monahan, Ronnie Wood, Warren Haynes, John Mayer, David Gilmour and more. Together they tell the tale of a truly remarkable man. As our mutual friend and official Allman Brothers historian John Lynskey said of Chuck: “Chuck Leavell is every journalist’s dream. Thoughtful, articulate and patient, Chuck turns an interview into a conversation. He lets his talent speak for itself, so there is no rock star ego to deal with. The master of preparation in everything he does, talking to Chuck is an absolute pleasure.” Lynskey couldn’t be more right. In our time together Chuck and I covered a good amount of ground. The conversation came easy and the stories told are ones that will remind you of how the brotherhood of rock and roll sometimes transcends even the music. The mutual admiration found on both sides of the Chuck Leavell story is well-footed against years of dedication to musical partnerships that know few equals. The tales told in the documentary (and often in this interview) explain how that magic founds its way to the songs we all hold so dear. The tales are as priceless as the songs they often inspired. I was moved by Chuck Leavell’s story. I know you will be too. Ray Chelstowski: This film won a People’s Choice Award at the Sedona Film Festival and I can see why. It really is an enjoyable ride for anyone who loves music. How did you approach establishing a balance between presenting your career, family, and your work with forestry in the documentary? Chuck Leavell: I have to give all credit for that to our film maker Allen Farst. We worked together for over three and a half years on the project and we had all of this incredible raw footage. There are the interviews with the folks I’ve worked with [in the music business] and then with people in the forestry world. Then of course there are the shots of Rose Lane and myself here in Charlane and also in Savannah, Paris and all that. I thought, “my goodness! How in the world is someone going to stitch this whole thing and make it a cohesive story?!” Allen said, “Chuck, this is what I do,” and he went into his basement for like six weeks and lo and behold he came out with something that I am just really pleased [with] and proud of.

RC: Allen Farst has made a broad range of films, everything from sports to entertainment. Did that influence your decision to move forward with him on this project?

CL: It wasn’t really so much about his body of work as it was about his commitment to the project. When we interviewed some other people they were like, “this sounds like an interesting project.” But Allen said, “Chuck, I really want to do this! I know I’m the guy to do this for you and I promise you that I will put my heart and my soul into this project. You just have to place your trust in me. I have a vision for it and I know that nobody can do it better than me.” So what do you say to that (laughs)? He convinced me that he really wanted to do it and would be willing to go the extra mile to do whatever it took to get it done right.

RC: You’ve said that it was difficult to edit the film down to 1:43. What did you leave out and what parts were the hardest to drop?

CL: Well there was some more concert footage of a show I did with a big band in Savannah. There were interviews with a lot other musicians I have worked with, like my good friend Randall Bramblett, and Davis Causey. There was also footage that was cut out of interviews. So Allen had the talent to realize what the hot spots and the highlights were and kept it to a reasonable time frame. I did talk to Allen about the possibility of a “Director’s Cut” where we would include a lot more footage.

One other thing I’ll mention is that while [the band] Sea Level is mentioned in the film, [they] didn’t get as much time as I wish it had allowed for. We were searching for a show we did at the Montreux Jazz Festival back in 1977 and we were starting to track down whether we could license it. Time started running out and we just couldn’t get there. So those were some of the things I wish we could have included.

RC: Like me, there’s a big age gap between you and your oldest sibling. I found that that age difference had a profound impact on the kind of music I grew to love. Was it the same for you?

CL: That’s a great point. I wish we could have gotten an interview with my sister, especially because she at one point worked at a record store. This was when I was just beginning to put together my first band. We would sometimes pool our money together because she could get a discount on buying LPs there. We would buy records together and share them. You’re right; my sister was definitely an influence and her ability to get these records that we both loved listening to was inspirational.

My brother is a whole different story. My mother had rubella when she was pregnant and he was born deaf. He now is a preacher and he has a deaf congregation in Memphis. Billy was very inspirational in a different way because of having overcome his deafness. He learned to lip read early on so we could communicate and he was a bit of a home filmmaker as well, and would make these amazing science fiction shorts where his character named “Ray Rocket” would fly to the Moon or Mars. He was quite clever with the limited resources that he had. The other talent that he had was cartoon art. He was excellent and I would imagine that he has the entire Bible, especially the stories of the Bible, done in cartoon art. He had a publication called Life of the Deaf. As you pointed out, family can be very influential in different ways and certainly my brother and sister were, and my mother and father were as well.

RC: In the film you talk about the secret of a long marriage. Having your wife with you on the road must be a gift and may have even saved your life!

CL: Absolutely, it’s been a godsend. When we do go out with the Stones, Rose Lane actually works back stage so she’s part of the Stones family as I am. We miss all of our friends, our characters that work with both [the] musicians and crew. The fact that she does travel with me makes life so much better for both of us and we’ve shared so many great times together with friends that we’ve made throughout the world. She’s been a great inspiration to me as well has been her family, especially on the environmental side. It’s really the love and dedication and passion that her family for generations have had for the land that inspired me to get involved as well.

RC: When you are playing with the Stones do the contributions made by the keyboardists who preceded you in the band have an influence on how you approach each song?

CL: Oh it absolutely influences me. I was a Nicky Hopkins fan before I ever dreamed that I would play with the Rolling Stones. I got to meet Nicky in 1982 when I did my first tour with the Stones. Ronnie Wood came to me when we were at Wembley Stadium and he said, “Nicky’s here man. He wants to meet you.” I was like, “oh man, are you kidding me? I can’t meet that guy!” Ronnie goes, “no, no, no, he’s a really nice guy. Loosen up. It’s gonna be all right!” And sure enough, [Nicky] was just as nice and humble as he could be. He said, “You’ve got a day off tomorrow right? Would you like to get together and have lunch?” So, we did, and we became friends and traded Stones stories. Over the years we wrote letters back and forth to each other. Of course this is back in the 1980s so it was before the internet. He was living in LA and I remember him writing me a letter after that big earthquake. He said, “I’m outta here! I’m not gonna live in a place where the ground moves!” So, he moved to Nashville and spent the rest of his days there as you know doing sessions.

He was incredibly inspirational. When I play a song like “Angie” that has his beautiful signatures, I know that I could never replicate them exactly, nor would I try, but I do try to do my version. The same applies to Billy Preston. When I was young, my sister took me to a Ray Charles concert and Billy was playing in the band. That became my first knowledge of him. Ray gave him a special part in the show where he sang a song, danced out front, and was playing the Hammond B3 [organ]. That’s when I began to pay attention to his career. Not only with the Stones but with others. He was a huge inspiration as well.

Stew (Ian Stewart) was the guy who really got me into the Rolling Stones. He promoted the idea of me being in the band. He tried to get me on the 1981 tour and that didn’t quite work out. But he did get me on in 1982 and Stew was instrumental in helping me understand the art of boogie woogie. I used to play that style with a certain left hand movement and he said, “hey man, you’re leaving out a lot of what you should be doing with your left hand.” He kinda corrected me and showed me patterns that really helped me understand that style.

The answer is “yes” to all of the above. And Ian McLagan by the way; in 1981 the band came to Atlanta and did an unannounced show at the Fox Theater. Stew called me up and said that “the guys are going to be in your back yard. Do you want to come up and jam a little bit at the show?” I said “Hell yes!” So I went up for that and I had some degree of trepidation as you can imagine meeting Mac, because he had the seat. I had auditioned and had admired his work and I didn’t know if there would be any tension. So I get called to go out on the stage and I’m playing a piano and Mac is playing organ, 90 degrees from each other. Bless his heart, he looked over his shoulder and said, “I see you’ve done this before, haven’t you?” And that really broke the ice. We became friends and communicated through the rest of his days.

RC: You have such a steady calming presence. I would image in working with Keith Richards and Mick Jagger that that has helped the band and the creative process.

CL: Well that’s a wonderful comment and I appreciate it very much. But you’re right, I try very hard at times to be a diplomat for the band. I think that one of the things that I believe makes a difference is being a good listener. I want to really understand what the concern is of all four parties. And then if I have a solid understanding of what they are thinking, then I can help mediate a little bit, left and right or between all four corners.

RC: It seems that throughout your career your addition to a band is about what you can do to elevate the music as opposed to just adding a “signature sound.”

CL: Yeah I would say so. I may have a style myself as I have been influenced by others as we talked about. When I’m going into a studio to record a track I always ask, what is the song asking me to do? What are the producer and the artist asking me to do? Again I think it goes back to being a good listener, to fully understand what the goal of the artist is and how can I help this track be a little bit better. That’s always what I try to do live. In rehearsals with the Stones with this incredible body of work, how can I contribute things that will make it a little bit better?

RC: As you note in the documentary, John Mayer has a songwriting style that is different than what you had been accustomed to but that you admire. Do you take something away from working with each musician?

CL: Oh my Lord yes! I say sometimes that any musician is lucky to have a degree of success with just one band. But the joy of my career is having all of this diversity. You make a great point about John Mayer, just watching the way he works. He just pushes and pushes until something comes out. That takes a lot of wherewithal, man; it takes a lot of determination and creativity. And of course chops. I mean, my heaven, John’s got chops in his hands, he’s got chops in his voice box, and then he’s got chops as a songwriter. You get to watch these people do what they do and I wish I could do it as well as they do. I’ve never been a great songwriter in that sense. I’ve written a few instrumentals that I feel good about. It is a learning experience and I feel that I am always a student of the people who I am working with.

RC: The only time where you appeared to be worried about work was when Sea Level had disbanded and the first Rolling Stones audition didn’t result in a job offer. It’s pretty incredible and such a testament to your talents to have remained in such steady, high demand for almost fifty years.

CL: I have been very fortunate and you are correct that was the one time where I did have concerns about my career. As the film depicts, that was also the same time that we moved to the country and began to investigate what we could do with our land. That helped fill that gap a little bit. But I had big concerns about whether I would be able to hook up with another artist, or [if] was I going to have to start another band. It weighed very heavily on my mind. Just as the film shows, I came home expressing all of this frustration and anxiety to my wife and at the end of it all she says: “yeah, well that’s interesting, but the Rolling Stones called you today.” I mean man, you talk about a turnaround? When that came out of her mouth I said, “look, Rose Lane, I don’t need a joke right now.” She said, “it’s not a joke Chuck. Here’s the number, go call them.”

So, I did, and got a woman on the phone. I had no idea who she was and said something to the effect of “listen, my name is Chuck Leavell and I understand that there are some people that might be looking for me and I’m happy to talk to them.” (laughs) You know I was trying to be careful of my wording! And sure enough it was Ian Stewart who called back within a matter of hours. I had a little trio that was playing at a place called The Cottage in Macon. I was somewhat surviving on doing that and so I said, “well Stew, this is amazing! I’ve got a gig this weekend. Can I come Sunday or Monday?” And he said, “we’d really like to have you there tomorrow!” So I had to go get the Tattoo You record and try to get a good feeling for the songs they might play off of that. But then I kinda had a talk with myself where I said, “Chuck, you’ve played Rolling Stones songs since you were fifteen in The Misfits. So relax, be yourself, go to the audition and have fun. Whatever happens, happens.”

Part Two will appear in Issue 134.

Photography by © Allen Farst.

0 comments