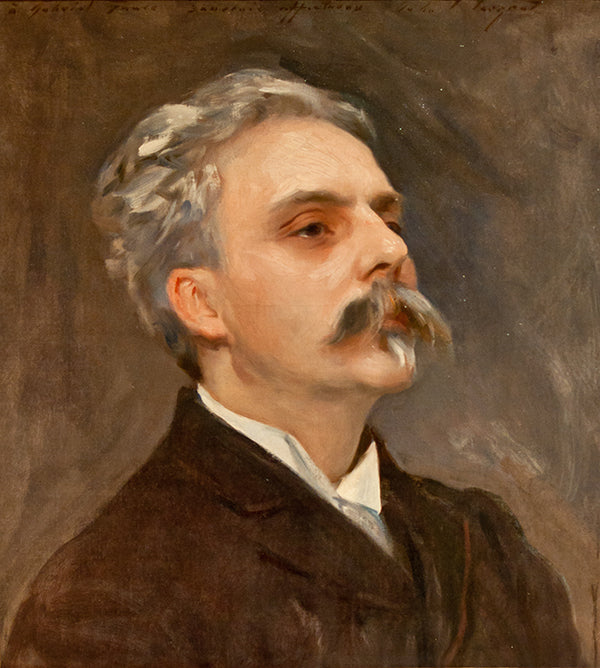

Soprano saxophonist/composer Jane Ira Bloom’s Picturing the Invisible: Focus 1 recently garnered a Grammy nomination for Best Immersive Audio Album. Produced and engineered by multiple Grammy winners/nominees Ulrike Schwarz and Jim Anderson, Picturing the Invisible: Focus 1 was recorded in ultra-high-resolution 384 kHz/32-bit as a live jazz album with the musicians, amazingly, all recorded while communicating from their respective homes via the internet. The album features Bloom, percussionist Allison Miller, bassist Mark Helias, and koto artist Miya Misaoka.

Following a special immersive audio screening of Picturing the Invisible: Focus 1 that included an animated manipulation of images inspired by photographer Berenice Abbott at the Dolby Screening Room in Manhattan, Ulrike Schwarz, Jim Anderson, and Jane Ira Bloom spoke with Copper’s John Seetoo on the making of the record and the technical and logistical obstacles that had to be overcome. Part One of this interview appeared in Copper Issue 181.

John Seetoo: You’ve used Skywalker Sound for mixing many of your projects over the past decade, and if I understand correctly, Ulrike said that you enjoyed mixing there but thought that recording a project like Picturing the Invisible: Focus 1 would not have been as successful if you had done it there. Is there a particular reason? Is it the reverb chamber in their space? A configuration that would have made it less successful?

Ulrike Schwarz: One of the real success factors of Picturing the Invisible is that we were able to take it out to Skywalker to mix. I mean, if we had been able to record it there, of course, that would have been even better. But that was, for obvious reasons, not possible. The idea of what I tried to achieve in the recording was to get a three-dimensional sound of the instruments but kind of exclude the rooms they were recorded in, because we knew if we were able to get to Skywalker for mixing, then we would be able to play this back into the [live] chamber that we built – these two elements in the recording room that we turn into a reverb chamber each time we go there. And that would enable us to put [the recordings of] those instruments into this incredible room, the Skywalker soundstage. I think that is where the [sound] mixer comes in, and where the mixer does his magic.

Ulrike Schwarz and Jim Anderson. Courtesy of Cecile Vaccaro.

Jim Anderson: John, part of being a recording engineer and a mixer is trying and hoping to get basically “really good tracks.” So, if I had no idea of what it took to get this far, I would just say, “Oh, these are really good tracks, I can work with them.” And a lot of times in the recording studio, all we need is a good, quiet room. What we don’t need is an amazing acoustic; what we need is someplace that’s quiet that we can actually place microphones in. [Percussionist] Allison [Miller’s] room was good and quiet. Ulrike could make sure that the microphones were placed properly, and [thus] getting the proper signals that then could be worked with. And so, we were able to actually create very nice immersive images through placement of the overheads and some room mics, and things like that. Then with the spot microphones on toms and snare drums and kick drums and things like that, we could actually then make the whole thing work. And so, that’s the trick. It’s just trying to get a good sound source to begin with.

JS: You’ve successfully recorded and produced previous records with Jane Ira Bloom and garnered awards and critical acclaim for those efforts. Can you compare some of the modifications you approached in recording her soprano sax for Picturing the Invisible: Focus 1, as opposed to past collaborative records like Wild Lines or Sixteen Sunsets?

Jane Ira Bloom. Courtesy of Johnny Moreno.

JA: Between Wild Lines, Sixteen Sunsets, and Early Americans, I’ve been able to do what I would tend to call a “modified” Hamasaki square, which is a square of four microphones. Ulrike can give you the exact dimensions of what a Hamasaki square is. But basically, what I do is I put down a carpet, and Jane can stand in the middle of this rug. The four microphones are about six, seven feet in the air. And they’re actually kind of recording above her, and those [mics] are pinning down the four corners of the surround [sound field]. If I were to strip that away, you would then just lose the space of the room that Jane is in.

But again, I’ve got a room that’s big enough to accommodate all this sound that Jane is making, and I want to capture that. The thing was, she’s in an office, which is about maybe a third of the size of [a] recording [studio] room, or maybe even smaller, that we would normally work in. And so, as Ulrike said, I don’t really want to capture that space too much. So, in stripping down to the bare essentials of what it would take to get a good recording of the soprano sax – that’s really what I had to work with. From there, I could then put that into the surround components [of the mix] to make that kind of stand away from the speakers and exist in this acoustic space that we create.

Also, Jane has this kind of Doppler effect that she usually goes for where she moves, and you can hear the change in the pitch of the instrument. Normally, we would capture that with an extra pair of microphones. And here, what happens is [that] we don’t have those microphones and you actually just hear the Doppler of her going by the microphones rather than opening up a pair and really getting the full stereo effect. That is another thing that we would normally go for. But in this case, she’s kind of just making the Doppler effect with the standard microphones that she would normally have [and not the extra pair we would use].

US: Also, usually when Jane does the Doppler, she has nothing around her, [so] she actually has the space to do the Doppler. If she had done this in her own office, she would have hit all kinds of things. That would have been very violent for everybody. (laughs) She had a much more limited space in which she could work.

JS: Did you wind up re-amping the tracks when you mixed at Skywalker, or use plugins or other kinds of treatments?

JA: Not really. First off, the tracks are actually, as I said, well-recorded, so we [were able to concentrate] on the mix…the only kind of re-amping was using Skywalker’s soundstage as our live [echo] chamber. So, if you’re calling that re-amping, yes, we were kind of re-amping. But, it’s the way you would work if you were in any studio that would have a live chamber, where we’re sending [the track] to an amplifier [and] speakers; that’s then being sent into the room, and we’re capturing that room. What we do is set up a cube of eight microphones. There are four in a square, and then four above that square, and that’s giving us the height [dimension]. So we’re re-recording sort of something in the general plane, and then we’re re-recording four more [channels] in the height above that. That gives us all the space we need to work with.

JS: The next bunch of questions has to do with impressions that I got upon listening to the recording. Off the top of my head, and some of these may just be my imagination or some of them the result of the actual recording techniques you use to challenge listeners: Given the limitations of the rooms you recorded the musicians in, was there a conscious effort to expand the sounds of the instruments for the immersive mix? For example, the first track has a 3D effect of other percussion coming from a space of several feet away from the drums, and Ulrike said that was spatially accurate. But was it? Was that recorded intentionally for that effect? Or was that something created in the mix?

US: Yes, that was intentional. It’s definitely set up for the bells. I set up a pair of coincident microphones, especially for the percussion, that was placed over the drum kit. And then I also had a pair of more traditional overheads that were closer to the cymbals. The two pairs have a time delay between them, because they were apart from each other – a natural time delay. So, I’m kind of playing with those two stereo sources to create an immersive image. Over basically a left, center, left to right, from front to back and left to right, you get this 3D [image]. I have this little video of [Allison Miller] twirling around the bells in a circle, and the combination of those two stereo techniques actually really reenacts what she was doing in real life. And since we had all the spot microphones close to the drums [we could] place [them] basically in the plane. And then you can either choose to move those two stereo pairs a little bit to the, say, to the upper tier of the speakers, and work in combination with this upper layer of the reverb.

There are several ways you can do it. You can either just concentrate all the microphones or direct them in, let’s say, the plane, and only have the reverb work up there. Or you can use a little bit of the upper microphones of the overhead microphones on the second plane, and add reverb to that. And that of course, I leave up to the mixing engineer. But I think the idea of making this – turning the drum kit into a big three-dimensional object – was definitely our intention.

JS: The kick drum on “Walk Alone” sounds massive, like the inside of a timpani.

US: That’s actually the floor tom! That massive thing was the floor tom! (laughs)

JS: Did that sound just come up serendipitously, or did you plan to have that?

JA: John, that’s the natural sound of that drum in the room. And it’s one of those things when you hear it as a recording engineer, especially in the studio, you go, “Wow, look how wonderful we are, we can capture that!” The idea is, you kind of stay out of the way of sounds like that, and try to let them grow naturally. And, it’s an impressive sound as it is. Ulrike once mentioned to me, “most drummers usually aren’t traveling with their own drums when you have them in the studio. They might use what’s in the studio, what’s available.” Here, Allison is playing a drum kit that she knows very well. She has tuned it; she knows what it sounds like. And this thing is just optimized to the hilt for the sounds that she wants to create. So she knows that this is an amazing floor tom and she’s got it tuned, and it really just, it’s just our job to capture that.

US: And she likes hitting it. (laughs)

Allison Miller’s drum set. Courtesy of Ulrike Schwarz.

JA: Yeah. You know, and then when the kick drum comes in, it’s a whole other sound in that same range, but it’s another tone that comes in. And we’re just happy that we can get that; she has the sounds, and we can record them and reproduce them.

US: In Allison’s case, it was great to watch. She just had all of her percussion toys, like, flying around. And she would just pick up whatever was sitting [there] in that moment. For me, sometimes watching my recording was one thing, but actually watching her doing what she did was much more fascinating. Yeah, because I was actually sitting in front of her; in front of the drum kit when we recorded it, so that was amazing. You don’t get to see that, ever.

JS: Was that on the video also?

US: I think it is. I have one video where she was playing percussion and doing the toms and doing everything. I mean, I just kept it to show Jane later what was going on, on our end, because [Jane only] just saw Allison’s face [during the recording]. I had the whole thing in full sight and it was very impressive.

JS: How did you choose where you’d be located when you were recording?

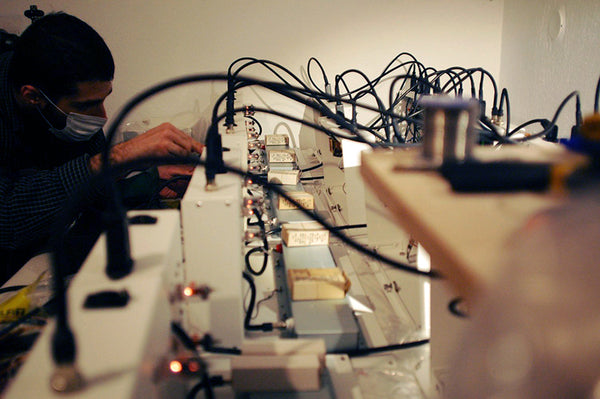

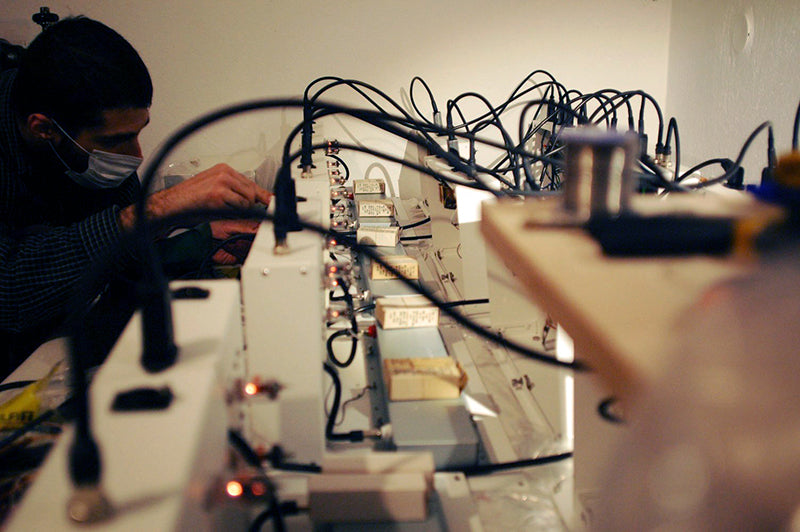

US: That wasn’t my choice. I took my small setup to Jane’s [office] and was kind of remotely hearing this over my computer that was with the other [musician]. But I knew that the bigger setups would be at the other place(s). With Jane, I know she is very, very disciplined. So once we had set up the microphones and I basically made a chart of where she would be, and where all microphones would be, then she would not change anything.

But with the other [musicians], I had to take a lot more equipment. And I didn’t want to leave that too long in other peoples’ houses. So, I chose to travel to the more difficult setups because [I knew] Jane’s would always be the same, and I could just leave it there. But with Allison, I had to go to her practice basement and for Allison, that was a 10-microphone affair. And the bass also [needed] many more microphones and the koto was also something between eight and 10 microphones, so they were much bigger setups.

And to get [in communication] with Jane [from the remote locations], I also had to find out what their internet looked like. That was always the interesting and the unknown part – of how the internet would react and how everything would be. So it made sense that I would be in the other person’s location, in the external location.

JS: So, Jane’s side of the recording was under your control?

US: Yes, yes. I controlled her recording computer via TeamViewer from my computer.

JS: On “Picturing The Invisible” Allison plays a hypnotic pattern that’s repetitive on top of the cymbals. It sounds like tuned percussion similar to Indonesian gamelan music. Jim, I think you said you’ve recorded gamelan in the past. I was wondering, was this intentional, or again, another serendipitous kind of thing?

JA: I think it’s just Allison being a percussionist and coming up with those sounds. Again, as a recording engineer and a mixer, we are staying out of the way trying to capture what was there. Of course, we’re trying to be true to that tradition too, and to make it convincing, and to make it work sonically. But it’s really Allison coming up with these amazing sounds that just make it very easy to make us look like we are just the audio geniuses that we are. (laughs)

US: We also only did very few takes in that recording. We did, I think at max, two takes of every piece. And the second take was usually completely different [from the first]. When Jane and Allison decided that something was not the approach they wanted to take they would have a discussion about what they wanted to change, usually for like 10 seconds, and then they would do another take. And the one that was chosen was the one [that sounded like] gamelan. So, they made decisions extremely quickly. And very often, they also made them while they were playing. In that case, in the recording, we had nothing to do with it. (laughs) Again, trying to stay out of the way.

JS: So, everything was just straight takes? Nothing was comped together from multiple takes?

US: No, no, no. At most, we had one edit.

JS: Mark Helias’s bass sometimes sounds almost like a synthesizer at certain points when he was using the bow and playing staccato. Was that the actual sound? Or did you do anything to it while you were mixing?

US: We had a stereo microphone in front of the bass and a microphone at the fingerboard, and a tube DI (direct input). So between the mixture of those sources – that’s where the effects came from. But it kind of sounds like that. We didn’t electrify anything in order to make that sound. That was really what was going on. Of course, the microphones were very close, but they weren’t any closer than in a studio recording.

JA: If we had done anything that would have been unnatural to the sound, both Jane and Mark, I think, would have objected to it. But that’s really Mark manipulating the instrument to make it sound the way he thought it should sound at the time.

JS: Might he have asked for, say, “can you put a delay effect on this? This is what I hear in my head.”

JA: No, no. There are no plugins, there’s really no EQ and there’s no compression. These are all just natural sounds as you [would] hear them if [you were] sitting there.

Mixing at Skywalker Sound. Courtesy of Jim Anderson.

JS: One last question regarding the sounds. You mentioned there were eight to 10 mics on the koto. In the mix there are certain parts where the sound of the koto seems to be focused from beneath the instrument and some where the sound seems to come from above it, or farther back. Were those decisions made during panning the sounds, or was that a result of each particular mic picking it up louder for those certain passages? And did the dynamics of how the mics were picking up sounds dictate how the final mix went?

JA: As you know, the koto is a very complex instrument to capture, and Ulrike basically treated it like it was a small orchestra. There’s a coincident pair in the center of the instrument coming through in stereo. There’s a stereo pair in the middle, and [another] on the side, what we would call outriggers. Now, you would do that, basically, with an orchestra. You would try to capture the stereo in the middle, and then you would try to get the sides. And so [the koto miking was] essentially that. There were also a couple of other microphones below, because there are holes in the bottom of the instrument where sounds are coming out. So we made sure to capture all that. The [sounds from the bottom of the instrument] are the ones that go into the LFE, the low frequency effects channels of the surround [mix]. That gives you good [low-frequency] support. Essentially, the instrument is radiating very much all over the map, and the trick is to have microphones capturing every one of these places where sound is emanating.

US: I think there is one other thing that is a little unusual about this koto. Usually, you expect the koto to be about maybe a foot over the floor, and very much use the reflection of the floor [in a recording]. But Miya places the koto more at a marimba height and the reflections come at a different point in time and have also a very different pattern than if [the koto] had been just above the floor. So, I had to [compensate] with my microphones below; I actually elevated the microphones that were below the koto to [pick up] the normal reflection pattern. That was the only thing that was a little bit unusual about that setup, but it definitely makes a difference whether you have a koto one foot or three feet away from the floor. I thought in the mix it came away like a traditional koto, but it was a little bit tricky to get the microphones, especially from below the koto, to a place where they would give me what I wanted, what I thought I should hear from them.

JS: I asked because I’ve never heard koto recorded like that before.

JA: You know, there are probably very few recordings of koto in immersive [sound] to begin with.

It’s kind of fun to be leading the charge with Picturing the Invisible because here’s a chance to actually hear percussion instruments and soprano sax – jazz instruments – in a context and in a format [where they’re] not usually heard. And so that’s where we’re always trying to push to try to do something that’s a little bit different, a little bit unusual. And potentially, we hope there’s a market for that.

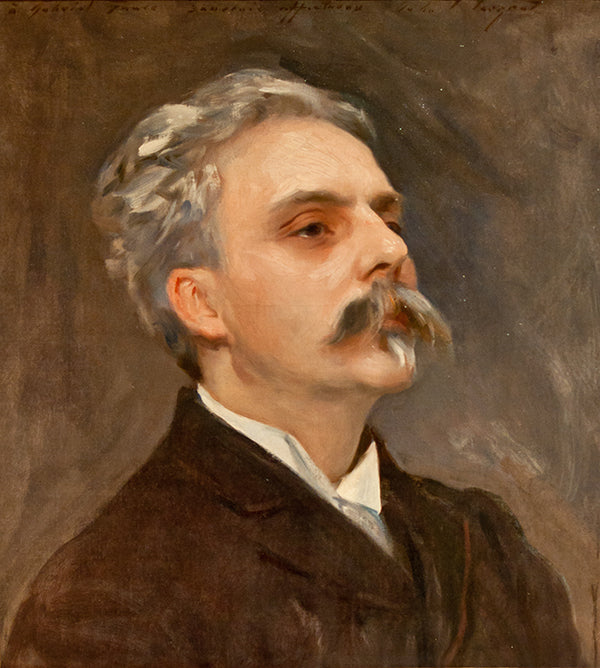

Jane Ira Bloom, Picturing the Invisible: Focus 1 album cover.

JS: As you’re both world-class engineers and producers, can you explain why you decided to ask Morten Lindberg to work with you on this project?

US: Yes, that’s actually a very good question. Morten Lindberg, first of all, we’re old friends with him. Second, we needed a mastering engineer. And of course, we love to work with Bob Ludwig. However, Bob Ludwig doesn’t have an immersive [mastering] room; he has 5.1. Since our task in this case was to have an immersive audio recording coming out of it, we decided to ask Morten to listen to the project at first, because he [had] built his new house in Oslo, Norway, and in this new house, he built this amazing state-of-the art immersive control room, in which he mastered this recording.

We asked him to take a listen to it and if he was interested in mastering it. Because, in my estimation, he is the person…and he loved the project and wanted to work on it.

Then, we also knew we had to get from our 5.1.4 channel-based master in 384 kHz to Dolby Atmos or something that we could actually sell. And [Morten] is, in my estimation, one of those people who knows the most about this translation.

And I think [he is] really on the forefront, because he talks to the Dolby and the Apple people, among others, [involved in the development of the immersive codecs] directly. We thought, if someone really can do this, it’s probably going to be him. I actually traveled to Oslo [to see him], and we were sitting there together and trying to decide on some of the parameters that had to be decided on. He is the person who turned it into [Dolby] Atmos, and he got the Auro3D encoding settled. And very, very importantly, he married the video to the audio.

We tried to license a science photo from Berenice Abbott as an [album] cover, but it was getting too expensive. So, I asked my friend Assen Semov in Berlin, who is a very, very talented 3D graphic designer, to kind of reinterpret one of those pictures. And he did that in a video rendering software but the cover of course, is a 2D representation of it. So while he was sitting there playing, we thought it would be really cool if that thing was going to just start moving. So we took advantage of the cover having been created in the 3D software and actually turned it into a little bit of a movie. It was very, very tedious and time-consuming work for Assen to render the time for the longest tune and then for Morten to turn the whole affair into a 38-minute movie with the chapters for each tune

So, the most time-consuming part of the mastering was marrying [the] video and audio and then turning it into the Dolby Atmos video with audio that it is now. Morten oversaw my stereo and the 5.1 mastering as well and then put it together with his 3D mastering and the video, so that now all formats can be sold on all streaming platforms.

JS: That leads to my next question: Picturing the Invisible: Focus 1 is available in a number of different audiophile formats. Since you had asked Morten to pretty much oversee the 3D format, outside of this format, were there any unusual challenges that you encountered?

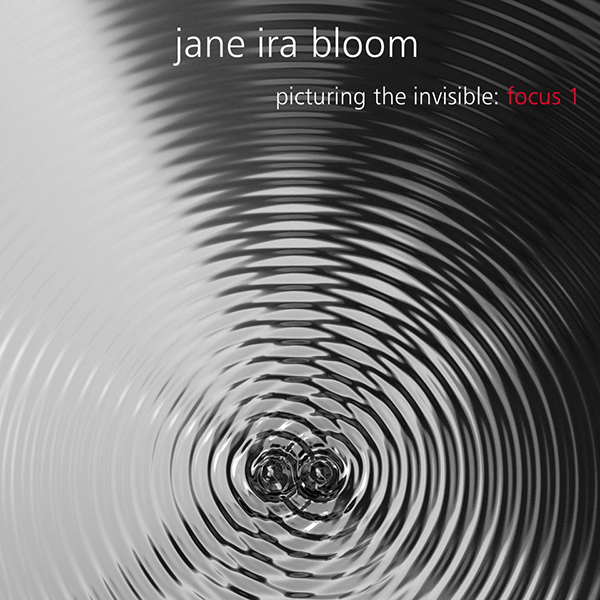

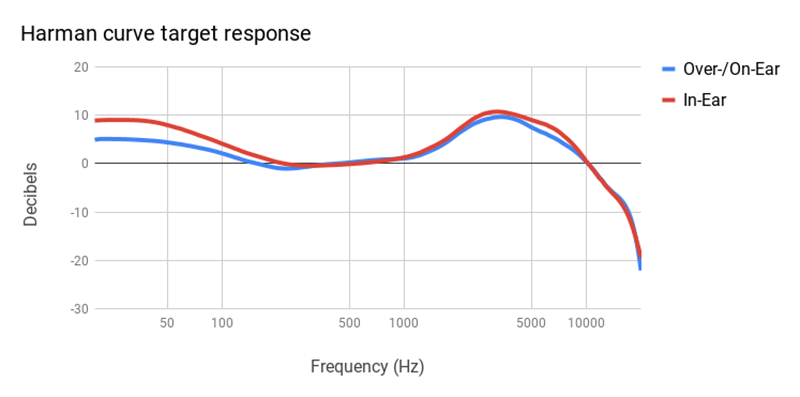

US: Actually, no. What we have learned and what we have noticed is that the higher the [resolution of the] format you make the recording in – like in this case, it was 384 kHz –the better your masters at lower resolutions will turn out. Another reason to go to Morten for mastering was that he works with Pyramix, like I do. So he can actually handle the 384 kHz. I chose 384 (kHz) as the recording frequency to go with a multiple of 48kHz, and not as I did with Patricia Barber’s Clique and Higher, which was to go with a multiple of 44.1 kHz. For one, because we knew this project was going to end up in Dolby Atmos, which again is 48 kHz, and it would probably be married or maybe married to a video. So that’s why it was in the multiple of the 48 kHz universe. That makes lowering the sample rate down to 192 kHz very easy if you’re coming from 384 kHz.

What we learned was when I gave it to Bob Stuart (of MQA) to turn “Picturing” into an MQA [format], that there was actually [using] one [type of] encoding for the first seven tracks, and then another encoding for the eighth because it had two passes of double bass. The double bass was the only part of the recording that has a little bit of ambient noise and so a different overall noise pattern. Bob Stuart used the “white glove” approach and gave each track the best encoding available.

And so running it down from 384 kHz, of course, made it possible [to preserve the sound quality] when converted to MQA. It’s the first MQA title sold from a file in 384 kHz and it’s the first 384 kHz [jazz recording] sold on NativeDSD.com. The sampling frequency of 384 kHz [enables us] to show the world what Picturing the Invisible [sounds like] in that kind of high resolution, and also [enables us to] get on our favorite platform, Native DSD.com. By now, it’s also available on HDtracks, in 192 kHz and several DSD formats. Then, we have the MQA that unfolds back to 384, and the Atmos and Auro3D versions are on an immersive audio album.

It was actually very comfortable to give every service what they wanted in any quality that they could handle. I do have to keep track of about 12 different master formats. But it has been the biggest fun putting up all the [versions] on the different platforms and basically giving everybody what they want and what they can play.

JS: Are you planning to perhaps patent this groundbreaking ultra-high-resolution remote recording system? Would you choose to use it again in the future?

US: Well, my brother is a patent attorney and he told me if I have used this system in the open already, I cannot patent it anymore. So that option is unfortunately off the table. But, I am using my experimental recording laptop all the time, on every recording I do. If people don’t object fast enough, they will be recorded in 352 and 384 kHz. And even if [our clients] only asked for a CD master, we will have the fun of having working with excellent tracks. I think once you have heard it, you cannot go back. Right?

JA: It’s true. John, you know, over the last 10 years, we’ve been working at Skywalker. And I remember the first time we opened up the faders and heard Patricia Barber in 352.8 kHz. We just said, “Okay, now this is a beautiful recording of her voice and we’ve never heard it like this before.” And ever since then, in 2019, we really haven’t gone backwards in any direction.

JS: I was referring to a process patent for the particular method of how Ulrike and you recorded Picturing the Invisible remotely, in terms of the communications and syncing things up.

US: Well, again, since we used the open-source program [Sonobus], I think my patent attorney family would probably say, “well, if you would have not done that in the open, you idiots, then it would be possible.” I haven’t talked about it [with them].

JA: You know, John, the whole thing was brought up by accident, frankly. And unfortunately, this wouldn’t be a process that we would like to do. (Ulrike laughs.) We wouldn’t like to do it again, if we don’t have to. Which would mean the whole world would have to go back to lockdown again, and we would have to work in this direction. You know, it’d be great to be able to get people back into the studio once again and be communicating directly. But this [remote recording process] was really meant as a workaround of not being able to get people together, not being able to record in the studio, but still do it in the highest quality we possibly could.

JS: But this is much different from in the past when you’ve had other artists overdub tracks, since you’re doing live jazz as an interactive and improvisational thing in real time. I’m just thinking that certain musicians who…maybe they’re too ill to travel or can’t come into the studio for some other reason, but this way, they can still be recorded.

US: Right. In the university universe, there is a program called JackTrip, which is the one that I would definitely use the next time; JackTrip uses the internet in a different way. It basically can connect various people, even over continents. The way that it uses the internet is [such] that it can keep the latencies even between continents, to a [small enough degree] so that you can communicate to make music.

And the other thing I would say: I come from broadcast, and if all this had been done via [using broadcasting] networks, [it] wouldn’t have been really that challenging, except for the 384 kHz part on both ends. There are a lot of studios like [the one used for] Teldex Berlin, or others, that have high-speed internet connections all around the world, where people can actually record in different parts of the world together with them in Berlin. I think the amazing part of [our method] was to do it on regular consumer internet [rather than on a dedicated network and/or bandwidth]. I think it was a great exercise for the purpose that we had to use it for. But unfortunately, I think there’s nothing patentable about it. (laughs)

JA: And John, the other thing is [that] the way most people [have been] using the internet [for live remote recording] is they were perhaps working with a click or looking at a conductor and kind of phoning in their part and then somebody else puts it all together. This was actually [all recorded] live. That’s the [unique] thing.

US: I would like to refine the process in case we had to do it again. I’m certainly not used to Sonobus and I don’t really want to [use it again]. I think there are better [systems] out at this point. It is an interesting way to do it if you have to.

JS: This is the last question. Are there any other projects that you’re working on that you would like to disclose to Copper readers? I think I saw a press release earlier today mentioning that you’re designing a new studio in Canada.

JA: We’re working with the Hamilton Music Collective [charity]. They’ve asked us to come up and help them with a studio that they’re designing, so we’re kind of putting in our two cents to help them. The woman in charge is an old friend, and she’s asked us to go there and consult with them.

We also have the Nataly Dawn project, by Nataly of Pomplamoose. We mixed her album, Gardenview Immersive Edition, in immersive, [and] that’s just come out.

US: Gardenview Immersive Edition is the most commercial [release] we’ve done in “our world,” because it’s not classical, it’s not jazz, it’s Americana and independent pop, so that’s a new adventure for us.

JA: I think the other one that’s just come out is (Swiss flugelhornist and trumpeter) Franco Ambrosetti’s Nora. It’s also in 5.1 surround via SACD.

JS: Thank you so much for taking the time for us.

JA: Thank you, John.

US: Thank you very much.

At the 2023 Grammy awards: Jim Anderson, Taylor Perry (Shore Fire Media), Jane Ira Bloom, Ulrike Schwarz, Maria Gamper (Tiroler Goldschmied), and Amanda Bloom (Crossover Media). Courtesy of Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images for The Recording Academy.

Header image: Jim Anderson, Ulrike Schwarz and Jane Ira Bloom at the 2023 Grammy awards. Courtesy of Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images for The Recording Academy.