1960s British music aficionados are likely familiar with many of the era’s historic music venues, including London’s Marquee Club and Saville Theater. Devout Beatles’ fans are likely to include in the mix Liverpool’s Cavern Club and Hamburg’s Kaiserkeller, where the boys honed their skills playing six hours a night, seven days a week.

Though not nearly as well known – especially among music fans on this side of the pond – was another venerable club with the very peculiar sounding name of Klooks Kleek.

From 1961 to 1970, Klooks Kleek operated as a jazz and blues club on the first floor of the Railway Hotel in northwest London. The club was founded by Geoff Williams and Dick Jordan, the former handling administrative duties and the latter club bookings. Jordan was the public face of the club. Known for his wry sense of humor, Jordan was a film cameraman by day and a club impresario by night.

The owners appropriated the club’s name from a 1956 jazz album by drummer Kenny “Klook” Clarke called Klook’s Clique. You’ll note Clarke’s album title is appropriately punctuated in the singular possessive, while the club’s name (Klooks Kleek) is devoid of any punctuation, to the dismay of English teachers everywhere.

With carpeted floors and walls curtained in red velvet, Klooks (or The Kleek, as some referred to it) provided fairly good acoustics, though still lacking in many of the accoutrements commonly found in modern-day music venues. The club didn’t have sound boards, sound engineers or even provide for band sound checks. The club’s stage was crudely constructed of sheets of plywood propped by wooden crates. The expectation was bands would show up, plug-in and play…and that they did!

Patrons wishing to attend a show at Klooks had to first become “club members.” Club membership wasn’t considered elite or economically challenging, as a lifetime membership only cost a mere shilling. Of course, members had to additionally purchase a ticket to any desired performance, with prices varying by artist.

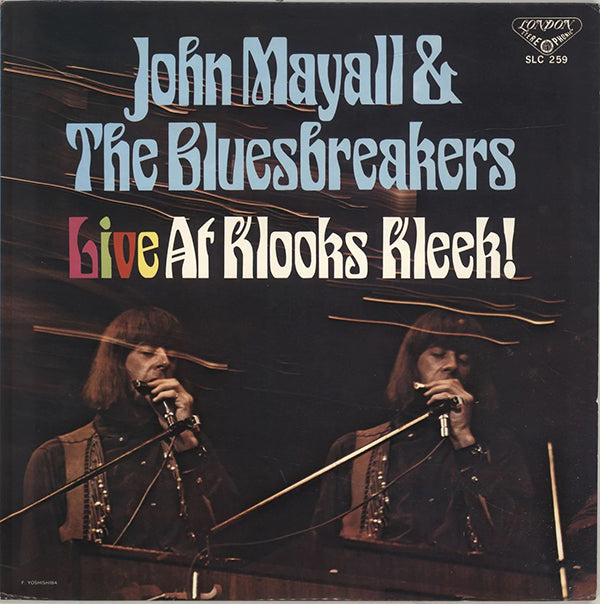

Klooks early offerings focused on contemporary jazz music, until American R&B began to strongly permeate the London music scene. The club formally shifted its booking strategy to R&B in 1964. Legendary blues artists like Sonny Boy Williamson, John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf and T-Bone Walker played the club, while John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers very first album release – John Mayall Plays John Mayall (Decca, 1965) – was recorded live at the club the same year.

The mid to late 1960s led to lots of experimentation among London-based musicians, with many soon-to-be well-known artists jamming with other soon-to-be well-known artists. It was like musical chairs or speed dating, with musicians seeking both great sound and strong band chemistry. Money and fame, yet to be realized by many, if any, were usurped by a love of craft. The notion that artists could achieve economic success, or even stability for that matter, was hardly a conscious thought. For the performers, it was all about the music.

Here’s a smattering of interesting performances and artist pairings that took place at Klooks:

– Appearing frequently at the club was the Graham Bond Organisation. The late Bond was a skilled vocalist, keyboard and sax player. His backing band consisted of Ginger Baker on drums, Jack Bruce on bass, John McLaughlin on guitar and Dick Heckstall-Smith on saxophone.

– In 1965 Rod Stewart’s Soul Agents opened for Buddy Guy at Klooks. Shortly thereafter Stewart joined Shotgun Express, with Peter Green on guitar and Mick Fleetwood on drums.

– A year later, 15-year old “Little” Stevie Wonder (that’s how he was billed) played the club.

John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers Live at Klooks Kleek, album cover.

– Cream (frequently billed as “The Cream”) played Klooks in August 1966. Proprietor Williams remembers drummer Ginger Baker asking, “how much money will the band be paid this evening?” When Williams replied 89 (British) pounds, Baker was quite pleased, as his band’s previous pay was only 50 pounds.

– In 1967 a young keyboard player named Reg Dwight (aka Elton John) played Klooks with his band Bluesology. That was the same year the original Fleetwood Mac with Peter Green, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood played the club.

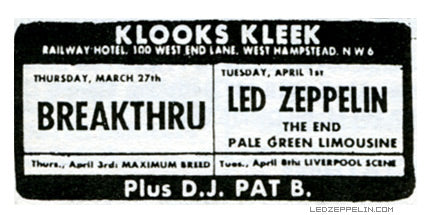

– Led Zeppelin played Klooks once in April 1969.

Ad for Led Zeppelin’s appearance at Klooks Kleek. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/public domain.

– Jimi Hendrix was never formally booked at Klooks, but he nonetheless did play there one evening. It was a period when manager Chas Chandler was showcasing Jimi all around London, and creating quite a buzz. During a break in John Mayall’s set Jimi borrowed a guitar from Mick Taylor and promptly took the stage.

Proprietors Williams and Jordan frequently utilized humor in promotional materials to differentiate Klooks from other London-based clubs. They also organized playful field trips and contests, including a 1962 members’ only photo contest. The contest judges were in the music business or employed in other creative crafts, including a photographer who specialized in nudes. The contest’s grand prize was 10 (British) pounds, with the winning photograph published in Melody Maker, a leading British weekly music magazine.

Williams and Jordan understood the importance of marketing and creating a unique brand image for their club. Other club owners would frequently complain about the large amount of free publicity Melody Maker gave to Klooks. Said Jordan, “I made frequent trips to their editorial offices in Covent Garden with bottles of scotch. I was told by someone at the magazine that Klooks was the only club that appreciated the art of giving.”

Jordan often liked to share amusing stories about Klooks. As he tells it, one evening two Decca Records executives entered the club and asked for opinions on two songs recorded by a contract singer of theirs named Tom Woodward. One song was greatly preferred over the other, and when it was released in 1965 under the artist’s new stage name, Tom Jones, “It’s Not Unusual” went to Number 1.

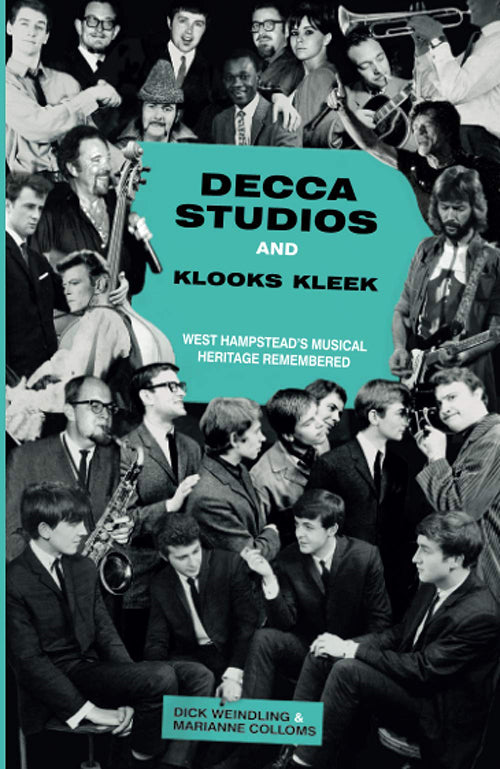

Klooks was fortuitously located right next to the studios of Decca Records. As a result, many music executives, producers and engineers often frequented the club. Aspiring musicians were very eager to showcase their wares, knowing that a titan of industry (or two) might be in the audience. Decca Studios’ close proximity also meant, if desired, that the label could produce live recordings from the club by creatively rigging cables and wires over the roofs of the two adjoining buildings.

Decca Studios and Klooks Kleek by Dick Weindling and Marianne Colloms, book cover.

My first exposure to Klooks Kleek was via the classic Ten Years After LP Undead (Deram, 1968), recorded live at the club. The genesis of that album has an interesting backstory.

In the late 1960s, proprietor and promoter Bill Graham wanted to book Ten Years After (TYA) at his Fillmore West and recently opened Fillmore East venues. But the band didn’t have a new album release to tour behind, considered a prerequisite at the time for going on the road. So TYA quickly decided to record a live album at Klooks, with the goal of distributing the LP solely to the US market.

In the words of TYA’s bass player Leo Lyons, “We didn’t have time for a new studio album, so we did a live album instead. The sound engineers moved a large sound board to the back of the Decca Studios’ complex, and retrofitted limiters, echo and reverb. They then threw cables and wires across the roof (from the Decca building) to the club.”

Club owner Dick Jordan introduces TYA on the recording. Knowing the plan was to release the live album exclusively in the US, Jordan humored the audience a bit about British accents, with the expectation his self-deprecating remarks would be edited from the final mix. It didn’t quite turn out that way. Here’s Jordan’s introduction as it appears on the live album:

“Ladies and gentlemen, as you know, this is going onto the air. If I speak like a cockney, maybe the Americans think everyone talks like a cockney, if I speak like that, it sounds so forced. But they’ve asked me to say Ten Years After…TenYears After!”

And with that intro Alvin Lee and company broke into the prophetically titled “I May Be Wrong, But I Won’t Be Wrong Always.”

The Undead LP firmly took TYA back to its jazz and R&B roots. It’s an astonishingly good recording given the primitive production that went into its making. Reflecting on the live album, the late Lee said, “I was so happy with it. When I first heard it I thought, wow, what are we going to do next? My attitude was, ‘Let’s go into the studio and experiment, because we’ve already made the ultimate (live) album.’” Undead’s critical success led to a change in the album’s distribution strategy to include geography well beyond the US.

In the end, the economics of a small club for 400 to 500 patrons just wasn’t sustainable. The Keef Hartley Band was the club’s last performer in January 1970. At the time of the club’s closing, membership had grown to 58,000.

The demise of Klooks Kleek was a precursor to what soon happened to several venues in the US, including the Fillmore East. Said Dick Jordan, “They (bands) can go play (London’s) Royal Albert Hall or the Lyceum,” similar to what Bill Graham would soon be saying about (NYC’s) Madison Square Garden.

Artist growth and economic opportunities simply outpaced the magic that iconic venues like Klooks Kleek and other clubs could provide.

Header image: The Graham Bond Organisation Live at Klooks Kleek, album cover.

0 comments