In response to last issue’s installment, a reader quite accurately pointed out that I’d skipped over RCA’s substantial contribution to the world of theater horn systems. Pleading ignorance rarely results in leniency from a judge, but perhaps our readers are more merciful. There’s very little reference material on the RCA stuff, and my personal experience with the gear is nil. I’ll gather more information and return to the subject when I have the goods.

It’s a funny thing— considering RCA was involved in every aspect of recording and broadcasting from making records to building transmitters and owning radio and TV stations, from being involved in movie sound recording to building and maintaining theater sound systems, it’s amazing that anti-trust actions weren’t taken against RCA, as they were against Western Electric. I wonder if Sarnoff’s political connections were a factor? I digress.

As previously discussed, by the late ’60’s, horns were almost extinct in American home hi-fi. The best-known survivors were the Klipschorn and the JBL Paragon; the Paragon was a custom-order item, and K-horns were rarely seen on sales-floors. Across the pond, there were still signs of life for horns, with attention from some unlikely sources. US magazines rarely mentioned horns, but John Crabbe, Editor of the UK Hi-Fi News, had published horn-construction articles in Wireless World in 1958, and in Hi-Fi News in 1962. In 1967 he went “go big or go home” with a series of articles in Hi-Fi News on the massive concrete horns he built into his home (you can find the articles here—scrolll down the page).

UK industry folks who heard the system still cite it as one of the best they’d ever heard. US hi-fi maven Irving M. “Bud” Fried, an early distributor of Quad and Decca in the US, was also part-owner of IMF speakers, and went so far as to sell driver kits and throat-molds so that ambitious DIYers could build their own concrete horns. I don’t know if anyone in the US ever did so.

Wireless World published a three-part series on horn loudspeaker design by Jack Dinsdale in 1974; the series is good basic reading although it has been widely criticized as misleading and full of errors. You can find the articles reprinted here—scroll down the page.

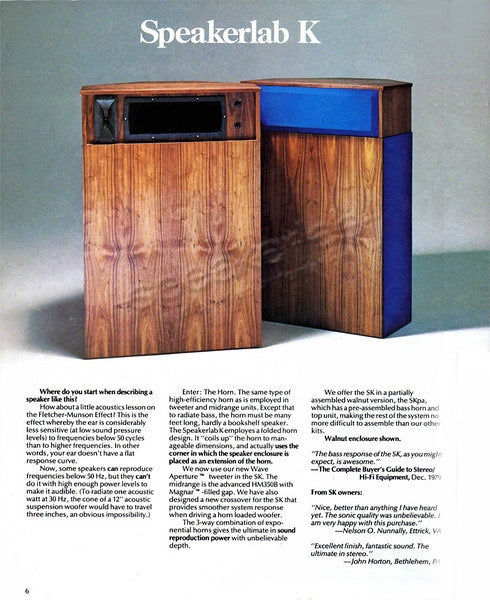

At the same time stateside, a Klipschorn design kit appeared from Seattle-based Speakerlab. Almost exactly the same size as the real thing, the Speakerlab K was said by many to have more extended bass than the “legit” K-horn.

That blue kinda GLOWS, doesn’t it?

The biggest, baddest, best-known American horn system of the ’70’s —aside from the Grateful Dead’s “Wall of Sound“—was the 5-channel home setup of engineer Dick Burwen, shown on the cover of the April, 1976 issue of Audio. Burwen began construction of the system in 1962, and 55 years later thinks it’s “about finished”. A close-up of the three front horns is shown at the top of the page, and full details are here. Burwen designed early products for Mark Levinson Audio Systems, as well as the killer Cello Audio Palette.

On the continent, Jean Hiraga was a conduit from the Japanese horn/triode culture to the west. Hiraga was Editor of the French journal l’Audiophile from 1977 to 1995, and often wrote for La Nouvelle Revue du Son (I think you can figure out the meaning of both titles) . I first encountered Hiraga in Paul Messenger’s “Subjective Sounds” column in Hi-Fi News, around 1977. Messenger referred to a survey article by Hiraga, in which he tested the distortion characteristics of amplifiers— euphonious tube amps showed mostly second-order distortion, nasty transistor amps showed mostly odd-order harmonics, and so on. It was ground-breaking at the time, and along with Matti Otala’s papers on TIM (transient intermodulation distortion), provoked a new examination of amplifier characteristics beyond standard static measurements.

Hiraga championed the old Altec 604 coaxial driver in a variety of enclosures, and brought the Japanese bass-reflex enclosure called “Onken” to Europe. The Onken was based upon the Jensen Ultraflex bass enclosure, which was originally a reflex-augmented corner horn; the Onken adaptation converted it into a smaller reflex box, more suitable for smaller rooms. Hiraga introduced the Japanese ultra-fi horn compression drivers to the western world, including brands like Goto (as used in the gazillion-dollar Magico Ultimate system).

The 1980’s saw a blip in the awareness of horns in the US, largely due to a series of articles in Speaker Builder magazine by Dr. Bruce Edgar, several of which are reprinted here . Edgar helped to popularize tractrix horn geometry, first postulated by Paul Voigt in the UK in the 1920s. Benefits claimed—compared to the more popular exponential horn geometry— were lower coloration and more even distribution patterns.

By the 1990’s the influence of Hiraga and the Japanese retro-fiers was seen on this side of the pond in Usenet groups and most famously in Joe Roberts’ magazine Sound Practices, which is seemingly better known now than it was during its publication run from 1992 to 1997. Sound Practices featured a historically-aware DIY approach, with an artsy undertone from articles by Herb Reichert, Gordon Rankin, John Stronczer, JC Morrison, our own Haden Boardman, and of course Roberts himself. The air of discovery combined with a self-aware smirk has not been duplicated since. Horn articles covered building a variety of enclosures for Lowther drivers, Mauhorns, and a wide range of Klipsch and Altec variants. The emphasis was on gear that could be worked on and with, not uber-pricey collectibles (although SP likely single-handedly caused prices of WE/Altec 755s to skyrocket).

Good luck finding these on eBay now.

After Sound Practices, the first home horn loudspeakers to attain a high profile in the audiophile market (and in the audiophile press) were those from Avantgarde Acoustic. Their flamboyant design and colorful paint schemes set the standard for all that followed, and made them prime camera-fodder. The brand became known for terrific sound at CES and other shows, as set up by their first US distributor, our own Jim Smith. While the brand is now well-entrenched in the audiophile marketplace and mindset, they have never again attained that initial level of acceptance and just plain good press.

The last 20 years have seen a sizable number of horn speakers appear on the market in the US as well as overseas. Due to their size and often-awkward styling, many remain highly specialized tweak brands. In the US we’ve seen Bruce Edgar’s designs, mostly in kit form (Edgar’s website is long gone); John Tucker’s Exemplar Audio has been around since the Sound Practices days, and currently makes a speaker utilizing modern production Altec 604s; Burwell & Sons speakers have been seen at a number of audio shows in recent years, and while bulky, are more attractive than most. They feature Altec and JBL drivers and handmade solid wood horns; Volti speakers show a number of design and styling cues from vintage Klipsch designs, and are highly-regarded; John Wolff’s Classic Audio Loudspeakers began by building reproduction JBL Hartsfields, but has since developed their own field coil drivers and built new horn speakers based upon the priorities of vintage horn speakers. There are dozens more horn builders in the US, many at the hobbyist-collective level; pro monitors with horn drivers are still made by numerous companies including Westlake, Ocean Way, and of course, JBL.

Horns never really went away in the UK, at least in the enthusiast world. Lowther, builders of extended-range drivers for well over half a century, have promoted horn enclosures designed by founder Paul Voigt since the company’s beginnings. Tannoy has been around for over 90 years, and for many of those years the name “Tannoy” was common parlance for a loudspeaker—ANY loudspeaker. Tannoy’s Dual Concentric coaxial drivers are often used in horn enclosures designed by the company’s founder, Guy R. Fountain, back at the dawn of time. Living Voice’s Vox Olympian and (slightly smaller) Vox Palladian systems take the English tradition of bespoke cabinetry to extremes, utilizing all Vitavox drivers. Speaking of whom: Vitavox has been around nearly as long as Tannoy, offering compression drivers for theater and pro systems, as well as the occasional home hi-fi systems like the classic CN-191 corner horn, as long-lived as the Klipschorn.

Elsewhere in the world, the Polish company Autotech produces a range of horn speakers (oddly called hORNS) including a top model which resembles the Avantgarde Trio if it’d been designed by Tim Burton, complete with sharp spiky feet that look as though they could skitter across the living room floor. Germany has more than its share of horn loudspeakers, including the acclaimed models from Voxativ, who also make their own Lowther-lookalike drivers. Auditorium 23 produces the Cinema Hommage which was seen on the cover of Stereophile, and fetures replicas of the WE 555 and 597 drivers manufactured by the Korean company Line Magnetic. Other German brands include Cessaro, Martion, Acapella, and many more.

In Japan, the unfortunately-named GIP has long produced high-quality Western Electric replicas, and recently showed their models next to the real things in the Silbatone exhibit room at the Munich show. A number of companies produce compression drivers and horns, including the previously-mantioned Goto. None are more-spectacular, however, than the giant solid wood baffle with horn hand-carved by Moriyama Meiboku, headed by the affable Tatsuyoshi Moriyama.

There is no way we could produce a comprehensive history of all horn speakers ever made worldwide, or even an all-inclusive survey of those currently made. It’s a vast field, frequently amazing and bewildering. I hope you’ve enjoyed this look at horn speakers past and present, and invite you to continue searching the field.

0 comments