-

Pianist and composer Billy Taylor (1921-2010) grew up in Washington, DC, where he took classical piano lessons with a man named Henry Grant. Grant’s other claim to fame in jazz history is being Duke Ellington’s teacher – so you know the level we’re dealing with here! Despite that impressive start, Taylor chose a sociology major at Virginia State College until somebody pointed out what an excellent pianist he was.

He moved to New York in 1943 and got his first regular jazz gig with the Ben Webster Quartet. Although he mastered the standards with a delicate swing style, he loved the burgeoning be-bop scene. Soon he would become as important for composing as he was for playing.

By the 1950s he started to establish himself as an important jazz educator; NBC hired him as music director of The Subject Was Jazz, the first TV show on that topic. Later in his career, he won an Emmy as a music correspondent for CBS News Sunday Morning. His accolades and respected positions make a mighty list, including the post of artistic director for jazz at the Kennedy Center.

Over the years, Taylor became an ardent activist for the well-being of aging jazz and blues musicians, a segment of the population without much of a safety net. But probably most important to him overall was his role as teacher. He referred to himself as an “urban griot” (even giving that name to his penultimate album in 2000), a keeper and disseminator of jazz knowledge.

Please enjoy these eight great tracks by Billy Taylor.

“Give Me the Simple Life”

Prestige

1953

Taylor’s favorite way to perform was with bass and drums, a configuration he always called the Billy Taylor Trio, no matter who joined him. Here’s one of the early versions, with Earl May on bass and Charlie Smith on drums. In 1953 this was released as two albums (Volumes 1 and 2), but all twenty tracks were combined for the 1995 CD re-release.

- “It’s a Grand Night for Swinging”

Urania

1956

-

“Get Me to the Church on Time”

ABC-Paramount

1957

Just because Taylor was becoming an important jazz composer didn’t mean he walked away from the standards. But when he played well-known repertoire, like the songs from the Lerner and Loewe musical My Fair Lady, he gave them a distinctive touch.

It’s interesting that, among that show’s sweet melodies like “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” and “On the Street Where You Live,” Taylor has included the comic, up-tempo number “Get Me to the Church on Time.”

The trombone solo is by Jimmy Cleveland, and Ernie Royal is again on trumpet. The arrangements are by a young man poised to become an American music icon: Quincy Jones.

- “Warm Blue Stream”

Riverside

1960

“Warm Blue Stream” is by one-hit wonders Sara Cassey and Dotty Wayne, who saw their song recorded by many jazz dignitaries, including Stan Kenton, Nat Adderley, and even the pop-leaning big band of Harry James.

As you can tell by the song-like phrasing, this tune originally had lyrics comparing a wistful love affair to the ripples of a stream. Taylor’s ethereal playing reflects that. Ray Mosca’s brushwork on the drums completes the worldbuilding.

- “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free”

I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free

Tower

1968

Taylor co-wrote the spiritual-like title song of this album, and it became his best-known and most-recorded tune. Taylor himself recorded it many times; this is his second version on vinyl, the one picked up by the BBC as the theme song for its Film Show review program.

This live performance with Ben Tucker on bass and Grady Tate on drums finds Taylor weaving through a number of different styles, from a chord-based laying out of the simple melody (inspired by typical church organ playing), to a decorated swinging toe-tapper, and then to a passage of complex harmonic shifts.

- “A Tune for Howard to Improvise Upon”

Taylor-Made

1988

In 1988, Taylor started his own record label, Taylor-Made. It lasted only two years, and he was featured on all seven of its releases.

This solo album is culled from live performances and, true to its name, has Taylor playing without the trio. For anyone who doubts that he could have mastered Liszt and Schumann piano works if wanted to, there are plenty of tracks here to make you a believer. My heart goes out to the “Howard” in the title, who is expected to improvise to this devastatingly difficult tune. (It starts at 4:05.)

- “Line for Lyons”

Dr. T (with Gerry Mulligan)

GRT

1993

One of Taylor’s many fine collaborations was this album with bass saxophone guru Gerry Mulligan, who appears on three live tracks. Mulligan’s early-’80s composition “Line for Lyons” is an angular bop tune, presented in the intriguingly hoarse yet singing tones of Mulligan’s bari-sax. But when Taylor comes in with his first solo, he smooths things out with a swing sensibility.

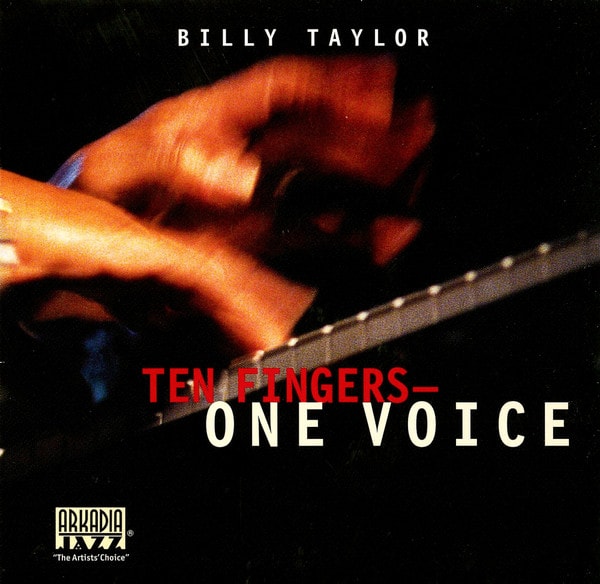

- “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams”

Arkadia

1998

Taylor was 77 when he recorded this solo album, one of the last few he made.

This standard tune dates back to 1931. Taylor opens with a slow version. His touch isn’t quite as light and silky as it was 45 years before, but the melody still sings and swings. But then he picks up the pace and starts to decorate the tune — It’s odd not to hear bass and drums come in at this moment, but the quiet sibilance of Taylor’s own unmiked scatting is percussion enough — with glittery passages and popping chords. And of course, there’s that harmonic imagination and the use of counterpoint, as if he’s a whole band unto himself.

0 comments