In Issue 186, I told you about a device I’d gotten that was reported to allow an SACD player’s HDMI output to send a native DSD signal to your DAC. The device was the TZT Digital Audio Interface, but as I told you last time, I couldn’t get it to work with my Yamaha SACD player. Sometime afterwards, I found a number of entries on threads on the web that stated that getting the device to work properly was entirely dependent on the SACD player, and it wouldn't work across the board with all of them.

I attempted to return the device to AliExpress, the Chinese company I ordered it from, but that ended up being a complete cluster. I pulled my hair out for weeks on end trying to negotiate with AliExpress and the seller to no end, and eventually filed a complaint with my credit card company. I thought that surely, at the worst, I’d get a credit on my card statement. But after weeks and weeks, my credit card company provided me with a letter filled with pages of bogus, half-truth info from the seller and AliExpress, and declined to make good on the charges. My loss was only about $55, but lesson learned – I’ll never order anything from AliExpress again. Ever!

I just spent almost an entire day finally sorting through boxes and containers in one of my upstairs closets that still hadn’t been unpacked since our move here to South Carolina. Those closets contain all my audio equipment boxes, cables, auxiliary gear, record supplies, overflow racks of CDs and Blu-rays, etc. As well as a table with my network gear and my digital library backup equipment – the room was a complete mess, and my wife Beth had been harping at me for weeks to straighten it out. While going through all the boxes, I ended up sorting everything into several piles to either pitch, recycle, or send to Goodwill. I stumbled onto the TZT Digital Audio Interface in its box, and immediately tossed it into the Goodwill pile, but ended up pulling it out to keep. If for no other reason, as a reminder of the debacle and to never order from an unproven online source again.

A Follow-Up on the Information I Received from Dalibor Kasac at Euphony Audio

I also mentioned in that last article that I’d gotten a series of emails from Dalibor Kasac, my contact at Euphony Audio in Croatia, telling me about a discovery they’d made about how delta-sigma chips from a certain prominent US manufacturer process native DSD. Also, that Euphony had gotten a couple of the new Topping E70 Velvet DACs that incorporate a pair of the newest generation of AKM chips (the AK4499 EX), and the AKM chips process native DSD very differently than those from the other manufacturers. They also noted that the DSD sound quality bettered that of the other guys in every possible way, and if I could possibly get my hands on one, I’d definitely be impressed.

I misinterpreted Dalibor’s explanation of the problem, thinking he meant the issue occurred when those chipsets processed native DSD via DoP (DSD over PCM). The problem is much more complicated, and my explanation from a couple of issues ago about how DoP played into the scenario was incorrect. Dalibor straightened me out and got me headed down the correct path, but by that point, my article had already been published. It was an unfortunate mistake, and several readers took issue with my assertions. All references to the misleading information were scrubbed from the article a couple of days after it went live. My apologies, but unraveling the intricacies of DSD is a bit more complicated than PCM – even when you’re staring at a schematic of the DAC chip's circuit.

The Topping E70 Velvet.

Jumping Through Hoops to get a Topping Review Sample

Dalibor had reached out to me in mid-February; I emailed Topping the same day, and it took about six weeks of jumping through hoops to get an E70 Velvet in house. Several days passed after I contacted Topping in China. I was then redirected to Apos Audio, their US distributor. Then several days passed before I was contacted by Apos, then about a week or so before I received a second contact from them, asking for samples of my published work. I provided them with links to multiple reviews from Copper, Positive Feedback, and Stereophile; then at least another week or so passed. I was sitting at my computer one afternoon when I happened to notice an instant message pop up from Howard Kneller (Copper, The Listening Chair, Sound & Vision). He asked if I’d reached out to Apos about getting a review sample of a DAC. They wanted him to verify that it was in fact Tom Gibbs contacting them, and not just some scam artist.

I confirmed to Howard that, yes, I had in fact reached out to them, and yes, I'm probably also a big-time scammer! Anyway, he gave me the necessary character reference (thanks, Howard!). A couple of weeks after that, I finally got an e-mail telling me that my request had been approved, and the DAC would be shipping to me within four weeks! I sent my contact at Apos, John, an e-mail asking, would it actually take four weeks? That seemed like an excessively long period of time, especially since it had already been at least five weeks since I had contacted them about getting a review sample. He told me no, that e-mail was essentially a “form” letter with “industry standard” language, and I’d be getting a tracking number within a day or so. Oh, and Apos was in the process of moving to new offices, so that might delay things a bit further. The E70 V finally arrived on March 30.

I’ve been writing for the audio trade for 20-plus years now, I maintain a fairly high profile, and I currently contribute regularly to a number of reputable audiophile web publications. I’ve also had reviews published in industry-standard print publications; one has the largest circulation of any audiophile magazine in the world. I don’t consider myself to be just some schmoe, and I’ve never had to put nearly as much effort into acquiring a review unit as I did with the Topping E70 Velvet. Literally 70 percent of the stuff I end up reviewing comes to me without any solicitation on my part.

I was describing how this all came down to an audio public relations professional recently, and she laughed, telling me that in her experience with Apos, they literally passed out review units like they were giving them to kids in a candy store. I like candy, but Howard Kneller then told me that Apos had apparently encountered a rash of unscrupulous individuals passing themselves off as “reviewers,” and that should explain their thoroughness in vetting me.

The beauty box for the E70 Velvet.

The Topping E70 Velvet Finally Arrives!

The E70 Velvet arrived encased in what the Chinese often refer to as a “beauty box”; it was probably the most elegant first impression of a product on this level I’ve ever experienced – such products typically show up in a rather plain and utilitarian cardboard box. I’ve seen this sort of thing from other Chinese manufacturers like Fiio, who tend to package their digital audio players and in-ear monitors in similarly impressive boxes. It’s a cultural phenomenon that we here in the US get little exposure to from American manufacturers, who tend to cut their costs at every point of the packaging process. The E70 V is available in either black or silver case finishes; my review sample arrived in black, and its appearance was both stylish and sophisticated.

The E70 Velvet is available in your choice of black or silver finish.

Included in the box was, of course, the E70 V, a 110V AC power cord, a USB cable, and a Bluetooth antenna. There was also a remote, which is small, but functionally well laid-out, and looks remarkably similar to the remotes supplied by Gustard – I’d bet they’re probably sourced from the same subcontractor. The box also included a printed manual and a warranty card. The manual was particularly useful, as the setup process is a bit less than intuitive. For the review, I used several cables I had on hand, including a Rite Audio HC power cable, as well as a Pangea Premier Silver USB cable. I attached the Bluetooth antenna, but never explored its functionality; I still believe – at this point, at least – that Bluetooth technology is half-baked in terms of audiophile quality sound.

The E70 Velvet didn’t budge, even with heavy audiophile cables attached.

The E70 V’s back panel is very well laid-out, and features a power switch, a standard IEC power input, inputs for a 12V trigger and pass-through, and the connection point for the Bluetooth antenna. Digital inputs include USB, coaxial, and optical; I only evaluated the unit using the USB input, which featured the highest level of file and bit-rate compatibility of the three choices. Analog outputs included a pair of single-ended coaxial jacks, and a pair of balanced XLR jacks. I evaluated the unit using the balanced connections. The outer case was substantial, with enough heft such that it didn’t move about or tilt backwards when all the cables were inserted (even the heavier aftermarket cables) – that’s always a nice feature! Fit and finish and construction detail were superb; the E70 V scores points on looks alone, and doesn’t appear at all to be a sub-$500 product. Upon turn-on, you’re greeted by a nicely-proportioned display, which allows you to see the sample rate of the file playing in really large characters that can easily be seen from across the room.

The E70 Velvet offers the usual selection of inputs and outputs found on a $450 DAC.

Setup of the E70 Velvet

As I mentioned earlier, proper setup of the E70 Velvet requires you to read the DAC’s relatively bare-bones manual, which will guarantee getting the best sound quality for high-end audio implementation. The E70 provides certain preamp functions like volume, input selection, and balance control, should you require them or choose to use them. As seems to be part of the current culture of small electronics in China, it appears the E70 V is as much directed at headphone users as it is for use as an audiophile DAC, and the preamp functions allow for easy integration with a headphone amp. That said, I'm using the E70 in an audio setup with a dedicated preamplifier, which makes those functions redundant, so I either disabled them, or simply didn’t use them during my evaluation, which was strictly for use of the E70 V as a digital-to-analog converter in a relatively high-end audiophile system.

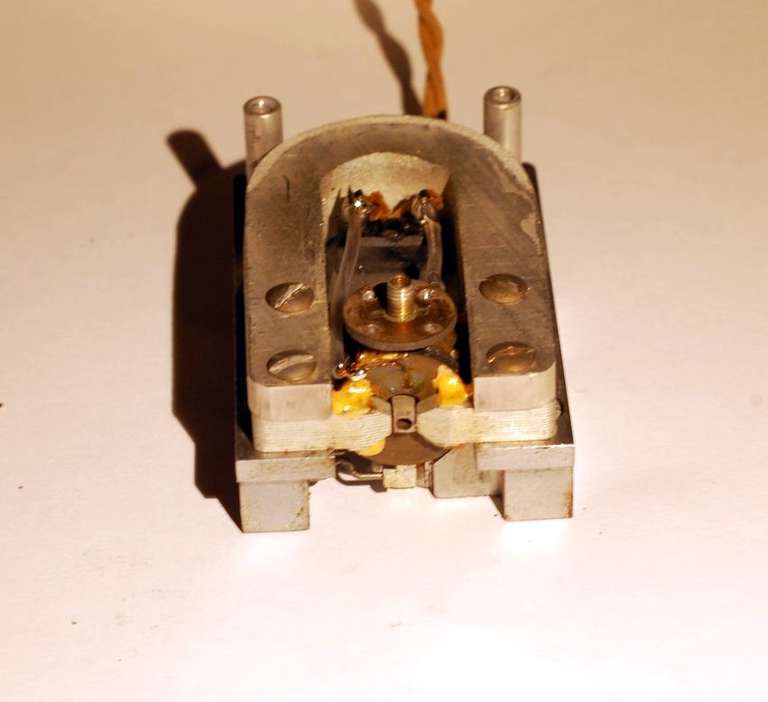

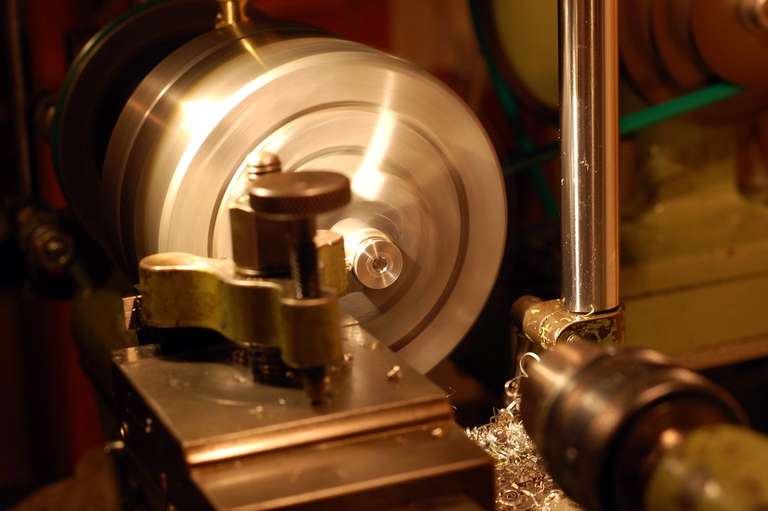

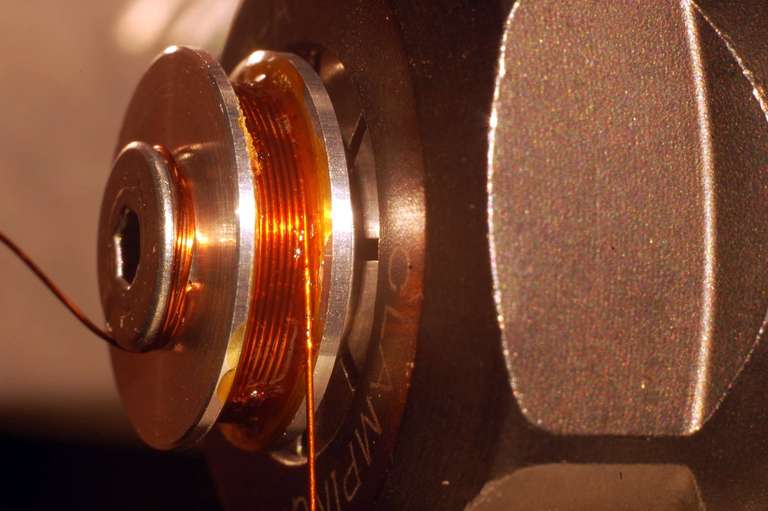

The E70 Velvet actually uses a dual-AKM chip configuration that accomplishes digital filtering, delta-sigma modulation, and the digital-to-analog conversion functions. Those chips are responsible for the magic that gives the E70 V its sterling sound quality with native DSD files. The "Velvet" part of the E70 Velvet’s name comes from the use of a single AKM AK4191EQ chip, which is a digital data converter chip that separates the digital filtering and delta-sigma modulation processes prior to sending the music signal to a pair of flagship AK4499EXEQ chips for digital to analog conversion. AKM calls this trademarked process "VELVETSOUND.” VELVETSOUND minimizes the effects of digital noise in the analog output, and results in a significant improvement in the E70 Velvet’s signal-to-noise ratio. The process results in a dramatic improvement in sound quality, especially that of native DSD files. Based on my auditioning, this dual-chipset configuration establishes a new benchmark of precision, performance, and musicality, especially at the E70 V’s low price point.

By turning off the E70 Velvet’s internal volume control, AKM’s dual-chip VELVETSOUND process allows digital filtering and delta-sigma modulation to take place without combining the native DSD signal with PCM. The native DSD signal is then presented to the digital to analog conversion stage unaltered.

I had made Robert Devcic of Euphony Audio aware of my plans for the E70 Velvet, and he informed me that I needed to make certain the unit’s volume control was definitely turned off. This has to do with the E70 V’s internal “magic” that gives it the edge over other delta-sigma DACs; turning the volume control “off” allows native DSD signals to pass through the AKM chipset without any conversion. Leaving the volume control “on” routes native DSD signals into the same path with PCM signals, converting them into a “shared language” that slightly diminishes the overall quality of native DSD playback. This was of paramount importance to me, because I personally consider DSD to be a superior playback format, and I have hundreds of DSD files in my digital library. While listening to DSD files was one of my main areas of focus while testing the E70 V, I also thoroughly evaluated its capabilities with PCM files of every available bit and sample rate.

With the rear-panel power switch turned on, the E70 V remains in standby; you then have to either turn the power on from the front panel’s multi-function touch button or with the remote. You’re then greeted by the really nicely-proportioned display, which is huge compared to other DACs I’ve encountered in this price range. To enter the setup menu, first turn off the rear-panel power switch, then press the front-panel volume knob and turn on the power switch. The volume knob is now a multi-function selector, and allows you to rotate through the menu choices. These include the display function (always on or auto-on) and brightness level, output level (4V or 5V, I chose 5V to match the output of the Gustard X26 Pro), choice of PCM digital filter (I chose the default), the various internal preamp options like channel balance and volume control (which I set to off), and selections for Bluetooth use (I also set this to off). You then press and hold the volume knob until “8-8” appears on screen, indicating that the E70 V is now set up and has saved your selections. You can also accomplish the setup routine using the supplied remote.

Use and Listening Tests

I’d been working on a review for the German-made Naiu Laboratory Ella Mark 3 power amplifier for Positive Feedback; you can read my published review here. I inserted the Topping E70 Velvet into my system midstream in that review process to try and replicate Dalibor Kasac’s positive impressions of a $450 DAC – while it was playing into a system that included an $11,000 amplifier. The $450 Topping E70 Velvet was used alongside my current digital setup that includes a Gustard X26 Pro DAC ($1,500 MSRP) and a Gustard C18 Constant Temperature clock unit ($1,600 MSRP). The Gustard combo sells for almost 9 times the cost of the E70 Velvet! I thought it would be interesting and instructive to compare the sound quality of the lower-cost Topping unit to that of the more highly-pedigreed Gustard setup.

My digital system is fully balanced; the PS Audio Stellar Gain Cell preamplifier provides system control, and the digital input chain is fed by a dual-box streaming setup that includes the Euphony Summus and Endpoint units. The Euphony equipment is built around their own Stylus operating system, which handles library management, music playback, and streaming. The Euphony gear streams the digital signal to the Gustard X26 Pro DAC via an i2S connection; a 10 MHz BNC connection shares the signal with the Gustard C18 external clock. Stereo balanced outputs on the Gustard DAC send the analog signal to the preamplifier, which in turn feeds the Naiu Lab Ella amplifier, which is connected to a pair of Magneplanar LRS+ loudspeakers with an REL subwoofer. It’s a fairly elegant digital playback system.

Adding the Topping E70 Velvet seemed at first to be a step backwards; the unit doesn’t feature either i2S or BNC connections, so a comparison between the Topping and Gustard units doesn’t at first appear to be apples-to-apples. The only option for such a comparison is to use the ubiquitous USB connection between the Euphony equipment and the E70 V; you can’t use what I’ve come to believe is the industry standard with i2S and an external clock. But USB has come a long way, and the USB capabilities of the E70 V either match or exceed those of the Gustard X26 Pro.

My main thrust for this review was playback of DSD files, including the hundreds of DSD64 rips from my collection of SACDs, as well as DSD downloads across a range of DSD64, DSD128, and DSD256 rates. I also listened to countless sources of PCM files, many of which were 16-bit/44.1 kHz rips from my collection of compact discs, along with rips of DVD-Audio and Blu-ray discs at 24-bit/96 kHz and 24-bit/192 kHz, as well as some 32 bit/384 kHz DXD downloads. Throughout the process, I continually compared A-to-B back-and-forth between the Topping E70 V and the Gustard X26 Pro/C18 combo. I listen to a very broad range of music of all genres, including classic jazz, jazz vocals, folk, classical, chamber music, opera, rock (including alternative, classic rock, and progressive rock), and even some metal, rap, and country/bluegrass. While I lean towards acquiring higher sample and bit rate files for my library, I’ve found that in my day-to-day listening, I generally get as much pleasure from a rip of a CD as I do from a much higher resolution file. High-resolution files generally hold up better for critical listening, but the vast majority of my digital music library contains 16-bit/44.1 kHz rips of my CD collection, outnumbering all other file sources by about 7-to-1 overall.

I listened to countless albums over the evaluation process, far too many to detail my impressions of each in a Topping versus Gustard scenario. But I did observe particular trends over the time spent comparing the two setups.

Topping vs. Gustard With DSD Files

The Topping E70 Velvet is the clear winner here. It bettered the much more expensive Gustard X26 Pro/C18 combo in every possible way with DSD files of every provenance. The dual AKM chips provide a clear path in their processing of native DSD that allows it to proceed through the DAC unaltered, with the only exception being the conversion from digital to analog. At the point when the AKM fire happened three years ago, a lot of folks online bemoaned the lack of availability of AKM chips, which I’d never heard at the time, in any implementation. I now fully understand their despair; the AKM chips are undoubtedly the very best available, especially in terms of how they process DSD playback.

Constantly comparing between the Gustard setup (which is nearly nine times more expensive) and the Topping unit revealed that the E70 V produced a sound that not only had greater levels of transparency and clarity, but was overall much more musical than the Gustard setup. And the DSD files as played through the Topping exhibited a much more pronounced stereo image, and helped my system project a much greater illusion of reality during playback. Not even the addition of the Gustard C18 master clock, which more than doubled its MSRP, provided the kind of improvement to its overall musicality to give it any kind of advantage over the $450 Topping E70 V.

When playing DSD files, the sound from the E70 V was lusher, richer, and much more analog-like than what I heard from the Gustard setup. There was an added measure of magic that was present during playback from the E70 V that was simply missing from the Gustard combo. I’d definitely attribute that to the more straightforward path the AKM chips use to handle DSD vs. the other guys. You know, sometimes less really is more! When Dalibor Kasac of Euphony Audio first emailed me about this, I was incredulous that it might even be possible, but trust me, hearing is definitely believing.

Topping vs. Gustard With PCM Files

I definitely gave the edge to the Gustard X26 Pro/C18 combo here. While the Topping E70 Velvet acquitted itself very well playing PCM files, there was a role-reversal of sorts that resulted in the same kind of playback improvement for the Gustard combo with PCM files that I witnessed with the Topping unit and DSD files. I mostly attribute that to the addition of the Gustard C18 master clock; there was a greater level of midrange liquidity and high frequency sparkle, improved transparency, and greater realism with PCM files as played through the Gustard setup vs. the Topping E70 V. That was especially true with CD-quality rips, which almost approached the level of higher-resolution files when played through the Gustard combo. As noted, the duo is significantly more expensive and overbuilt compared to the E70 V, so it’s no surprise that the Topping unit couldn’t match the Gustard’s overall sound quality with PCM files.

One other thing with regard to PCM playback with the Gustard: it’s MQA-capable. Those in the audiophile world who are vested in MQA are doubtless unhappy with the recent events surrounding MQA’s financial troubles, and the end may be in sight for the nascent audio format. That said, at the point when I made the request for a review sample of the Topping E70 V, I didn’t notice that it wasn’t equipped for MQA decoding and playback. That’s not a deal breaker for me, because at that point, I didn’t have a Tidal streaming account, and I didn’t have a single MQA file in my library.

Of course, the minute I delve into MQA, they file for administration!

But in the protracted period it took to get a review sample, I decided to order a Japanese MQA-enabled compact disc of the Yes album Drama. It happens to be one of their albums that hasn’t been remixed or remastered by Steven Wilson, and probably won’t be. I mainly ordered it to take a serious listen to the MQA format for the very first time. After getting the disc and ripping it to MQA-enabled FLAC files, I then attempted to play it back over the Topping E70 V. I could only get 44.1 kHz PCM to display on the unit’s front panel, and after an hour of consternation, I started digging online and discovered that the E70 V is not, in fact, MQA-enabled.

How I missed that, I’m not completely sure, and whether Topping had some advance warning that MQA as such might be going away soon is an unknown. Regardless, I then routed playback of the MQA-enabled files through the Gustard setup, and I thought Drama sounded really great – maybe even better than I’d ever heard, other than perhaps the LP version. I liked it so very much that I ordered the MQA CDs for the Yes albums Tormato and 90125. The day after placing my order, the news hit that MQA had filed for administration, which in the EU is similar to a bankruptcy restructuring in the US. Talk about bad timing! YMMV, and you may (pretty much like me) not have any deep-rooted feelings regarding MQA, but if MQA is an itch you have to scratch, the E70 Velvet can’t assist you in that area!

Conclusion

When dealing with high-end audio gear, I’ve often found that a fairly substantial investment in equipment has to be made to achieve a relatively minimal improvement in overall sound quality. That simply is not the case with the Topping E70 Velvet and its ability to render DSD sound with a level of detail, clarity, and musicality that DACs I’ve heard at nearly 10 times its price point can’t match. The Topping is an exceptionally well-made unit, and the dual-AKM chipset implementation is clearly the principal reason for its impressive performance. This gives me pause to reconsider how the price point of high-end audio equipment should relate to sound quality. The Topping E70 Velvet DAC doesn’t cost an arm and a leg, but sounds like a million bucks, and it comes very highly recommended.

All images courtesy of Topping, Apos Audio, and the author.