As a result of COVID-19, AES (Audio Engineering Society) Show Spring 2021, named “Global Resonance,” was conducted online from Europe. This afforded me the rare opportunity to view a number of the presentations, which would have been otherwise impossible.

This show leaned more heavily on the academic side of audio technology than the New York-based AES Show Fall 2020. In Part One of Copper’s AES Show Spring 2021 coverage (Issue 139), I looked at presentations on binaural audio, audio mixing for residential television viewing environments, and an analysis of differences between Western and Chinese hip-hop music. Part Two (Issue 140) focused on psychoacoustics and studies on emotional responses to sounds. Part Three will delve into the technology side of audio transmission, and achieving realism using sampled orchestras.

The Technology of Streaming

David Bialik (Chairman of the Broadcast and Online Technical Committee at AES) hosted a symposium about streaming technology with Tim Carroll (CTO, Dolby Labs), John Schaab (marketing director of Stream Index), Robert Minnix (product manager, StreamGuys), Robert Marshall (co-founder of Source Elements), and Scott Kramer (sound technology manager, Netflix). They discussed the different audio codecs currently in use and explained some helpful tips for compliance with audio specification requirements.

Scott Kramer pointed out that Netflix’s primary codecs are Dolby Digital Plus, Dolby Digital Plus JOC (Joint Object Coding), and xHE-AAC. Netflix’s policy is to adopt market-proven and successful codecs that support the widest audience of device users, rather than trying to do R&D on its own.

Netflix uses a Dolby Professional loudness meter with Dolby Dialog Intelligence to measure all audio for its cloud encoding platform. All audio delivered to Netflix is aligned to -27 DRC (Dynamic Range Control) with a +/- 2 leeway for dialog. This was chosen to give the vast majority of Netflix library content compliance with the EBU R128 loudness normalization standard, and has given audio consistency to Netflix programming from title to title, whether a feature film, documentary, sitcom series or any other genre.

With the advent of new codecs like xHE-AAC, Kramer noted that Netflix was doing some tests with metadata-based dynamic range control, setting a dialog level of -16 DRF for mobile devices only. The primary goal is to offer volume consistency across the board using different Bluetooth devices.

Audio mixers have embraced the 2018 Netflix shift to its focus on DRC rather than being measurement-based, as DRC allows them the freedom to set music and effects levels to taste while referencing a dialog level standard to minimize inconsistencies.

Dolby also has new adaptive streaming engine processes that allow bit-rate changes in the codecs in Dolby Digital Plus (from 192 kHz to 640kHz), but it is still in the development stage with an eye towards wide scale integration by Netflix.

Tim Carroll from Dolby cited the huge challenges over handling metadata back in 1995 and the genesis of HDTV, when audio only needed to hit a single set of metadata at the time. The innovations created in the subsequent 25 years use metadata in a multiplicity of ways that would be inconceivable before 2000. Parameters for delivering metadata have expanded since then, and a great percentage of the process is now on autopilot and fed to the encoder. Support in next-generation audio system codecs, like Dolby AC-4, is vastly improved. As long as metadata can separate the content from the metadata delivery so that the decoder can properly apply the metadata, this will be the key for new developments.

Metadata gives a predictable endpoint for content, but is not going to fix anything on its own. It allows for better device control of a mix so that the mixer can tailor the sounds to the final destination.

John Schaab was enthusiastic about the proliferation of 5G and how it will aid in streaming reliability, which has been a persistent problem. Content delivery systems need to develop improved efficiencies and reliability, as the pandemic has caused a greater strain on broadband resources, with more people working at home, more use of Zoom meetings, and increased demands on streamed home entertainment and Internet Of Things (IOT) use.

The explosion of podcast radio is the only area of significant growth in the broadcast arena, and Schaab believes that while audio quality is important, technology has already achieved that to a fairly high degree, while delivery reliability is still lagging behind. This is because back in 1998, nobody envisioned the extent of enterprise use that the internet would be tasked to deliver. He credits Dolby Labs with taking the plunge to support xHE-AAC, which has led to a bunch of other players getting involved for further R&D, and noted that RTMP and Flash, once popular formats, are no longer supported due to their high error rates.

Schaab also praised Apple’s HLS, and DASH streaming using segmented audio, which breaks the data into timecode “bitbucket” packs, so that if there are dropouts, the playback can be recreated with sync intact if there is a large enough buffer. He noted that Netflix’s video streaming was what really established HLS as a format, and its reputation for reliability as the main attraction for podcasters. HLS’ handling of metadata also allows for titles, artist details, album graphics and other information that can accompany audio. Additionally, HLS and DASH lower costs, since the user no longer has to pay for a media server.

Schaab is very optimistic about the future, and believes that platforms like xHE-AAC hold the key to real-time streaming with only milliseconds of latency, a next level of advancement over bitbuckets.

Robert Marshall commented on streaming in peer-to-peer workflows, where each computer can act as a server for the others. In his work, the primary balancing act is in stability vs. latency. Wi-Fi vs. Ethernet connectivity can make a big difference from a transmission perspective (with Ethernet typically being more stable). Firewall problems add latency because of detouring servers used in peer-to-peer streaming.

Marshall finds that consistency is more of an issue than bandwidth. Another crucial consideration is mismatched uploading and downloading hardware capabilities, so sometimes streaming to a central location hub that then routes the lowest common denominator rate that works for all stakeholders involved is the solution, especially in audio productions involving ADR (automatic dialog replacement) sessions with multiple users.

Consumer systems can prioritize intelligibility over audio quality, so applying a fixed bit rate and other parameters with a bigger buffer can help with quality. Removal of echo cancellation, which also taxes CPU power, can also improve workflow.

Screenshot from “The Technology of Streaming,” courtesy of AES.

Robert Minnix elaborated further on the incorporation of metadata into the workflow and the Secure Reliable Transport (SRT) video transport protocol and how it adapts an encoder to whatever conversion format it encounters.

David Bialik commented on his committee’s work in trying to set standards for loudness in both audio/video and audio-only streaming, with recommendations to be codified this summer. He stated that AES standard audio-only streams will be at -18 LUFS (Loudness Unit Full Scale) and -24 LUFS for video.

In the roundtable discussion, there was a consensus that most clients prefer to stream in both a 128K bitrate AAC LC and a 64K bitrate in ATAC. This covers both PC and mobile devices. For video production, Netflix asks pro streaming partners for an ability to go higher. The bit rate for Netflix will go down to 32K for limited-bandwidth situations, and go to 512K if possible..

Most agreed that below 96K, compression was noticeable at times, but definitely in a video production environment. A push for “lossless” video has increased, but it’s important to still be cognizant of limits on the part of many streaming viewers’ hardware.

Screenshot from “The Technology of Streaming,” courtesy of AES.

Scott Kramer summed it up, referencing the fact that most people who may even have streamed in 5.1 in the past “were unaware of what they might have been missing,” so the goal at present is to treat every potential listener as an audiophile and for content providers to stream material with the maximum quality audio possible. The ones who can appreciate it now certainly will, and the ones who can’t at present may be able to do so in the future.

Advances in Realism in Sampled Orchestra Performance

Composer Claudios Bruese presented a look at the strides made with digital samples of orchestral instruments in performance in his presentation, Advances in Realism in Sampled Orchestra Performance.

Bruese noted that the term “orchestra” is a loose one and can apply to anything from a 10-member chamber music ensemble to a 200-piece full Western music symphony orchestra, replete with strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion, and other instruments. In each case, the musicians are all playing in the same space, often recorded with multiple microphones that not only capture each instrument group, but the sound of the room and its reverberations as well.

Screenshot from Advances in Realism in Sampled Orchestra Performance, courtesy of AES.

When trying to realistically recreate the sound from these types of performances with digital samples, there are a number of challenges, among them:

- Getting the samples – a task in itself, a complicated process that involves recordings of each individual instrument over the full range of that instrument. The recordings also have to include different dynamics, articulations, and other nuances and techniques unique to that particular instrument.

- Once the musical composition is chosen, each instrument has to be recorded in its entirety in accordance with the score, as opposed to when multiple players perform concurrently. This process is akin to multi-tracking in popular music, when someone like Prince would overdub all of the instruments himself for a recording.

- Once recorded, the project needs to be mixed, again, similarly to the way a multi-tracked recording would need to be mixed down to the chosen listening format(s) for release to the public.

Overall, the process is significantly more time consuming and labor-intensive than real-time recording a live orchestra. However, due to budgets and the grossly reduced number of recording studios that can accommodate recording live orchestras in a professional manner, sampled orchestras have become more and more prevalent, particularly in the film and TV media worlds, where music may be just another post-production budgetary line item with a hard deliverables deadline.

Bruese compared a 1986 composition he recorded with a Sequential Circuits Prophet 2000 synthesizer, with a maximum of 8 seconds per note memory capacity, playing factory samples as a basis of comparison to currently-available sounds. He pointed out how the Prophet 2000 sounds were static due to the memory limitations on the range of note articulation, and how the overall quality of the recorded performance was somewhat mechanical-sounding as a result. Real-time dynamic control was non-existent, so brass instruments, for example, sounded very much like they were being played on a synthesizer, as the sample did not contain the additional note nuances the way an actual horn player’s breath would have shaped them.

These limitations were characteristic of 1980s low- and-medium budget TV and film soundtracks, stated Bruese. The technology would improve over the next decade, as EMU’s Emulator and other sampler instruments would emerge on the market with greater memory storage and better features. The ability to have minutes’ worth of sampling time to capture a greater range of note colors, as well as improvements in sequencing and digital recording such as Pro Tools software, led to great strides of improvement for sampled orchestral performance recording.

Screenshot from Advances in Realism in Sampled Orchestra Performance, courtesy of AES.

Sequencing (the ability of a synthesizer, device or program to generate a sequence of notes), in particular, once it was improved to include MIDI velocity, pitch bend, portamento, vibrato, and timing quantization, provided much greater flexibility in giving performances more of a “live” feel. Minor tweaks could be made to individual notes without committing them to tape and not requiring multiple playback devices running simultaneously.

A subsequent example from one of Bruese’s film scores circa late 1990s-2000 displayed the ability to overlap and cross-fade additional (synthesized) instruments in a more realistic context within the sequencer. The woodwinds section still had a trace of digital sampling artifacts but was otherwise vastly superior to the woodwind sounds in his 1986 piece. Most importantly, brass instruments could now play legato sampled phrases, something that limited sample memory previously made prohibitive. Bruese noted that in order to approximate legato notes on brass before legato samples could be obtained, he would have to painstakingly add MIDI vibrato and pitch bend commands to simulate breath articulations that were unique to the horn tracks for each instrument.

In his third composition, Bruese actually recorded his own instrument samples to his personal satisfaction. Using a computer-based DAW (digital audio workstation) instead of separate hardware devices also enhanced workflow flexibility. This allowed Bruese to fine-tune strings, for example, so that distinctions and nuances between alternating pizzicato and staccato notes could be performed and recorded the way they would be done in real time by actual string players.

Screenshot from Advances in Realism in Sampled Orchestra Performance, courtesy of AES.

As the technology developed, Bruese’s ability to re-create a genuine Western symphonic orchestra was enhanced accordingly. The use of the now-industry-standard Pro Tools platform and a setup featuring samples of the individual strings of each virtual string instrument enables him to create unique and more realistic string-instrument sounds instead of relying on prerecorded ones. This allowed him to use pitch bends, portamento, and other techniques to emulate string players’ finger slides for each stringed instrument.

Bruese’s presentation gave both a good historical overview as well as the work involved in the creation of sampled orchestral performances, something that is routinely overlooked by film and video producers, especially those for whom music is an afterthought.

Next issue, the final installment of coverage of AES Show Spring 2021 will focus on sound design for video games, and a tribute to the late Rupert Neve, one of the most brilliant engineers the audio world has ever known.

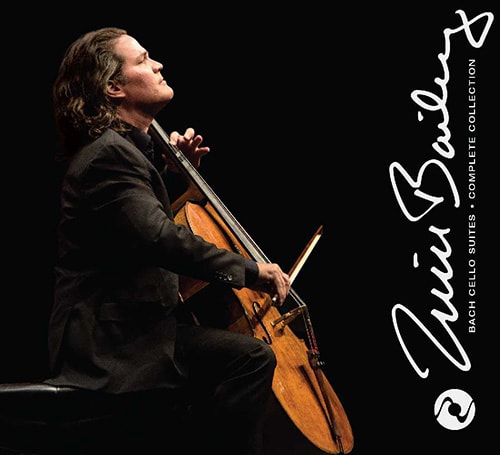

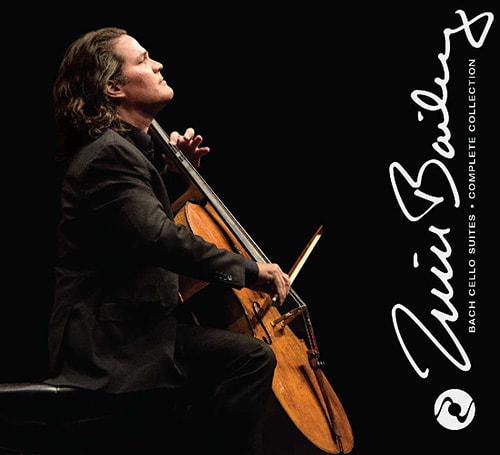

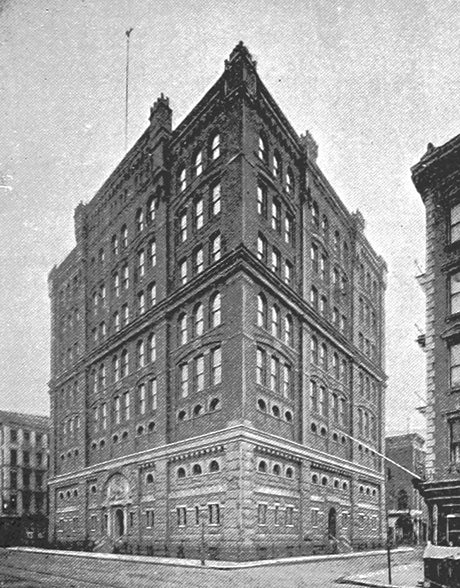

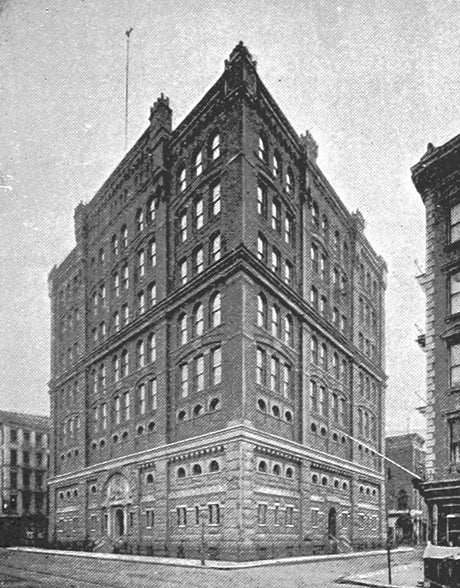

The Ikeda Theater at the Mesa Arts Center, where The Complete Bach Cello Suites was recorded.

The Ikeda Theater at the Mesa Arts Center, where The Complete Bach Cello Suites was recorded.

Ken Sander, 1966.

Ken Sander, 1966.