Loading...

Issue 131

Is There a Thinking Cap?

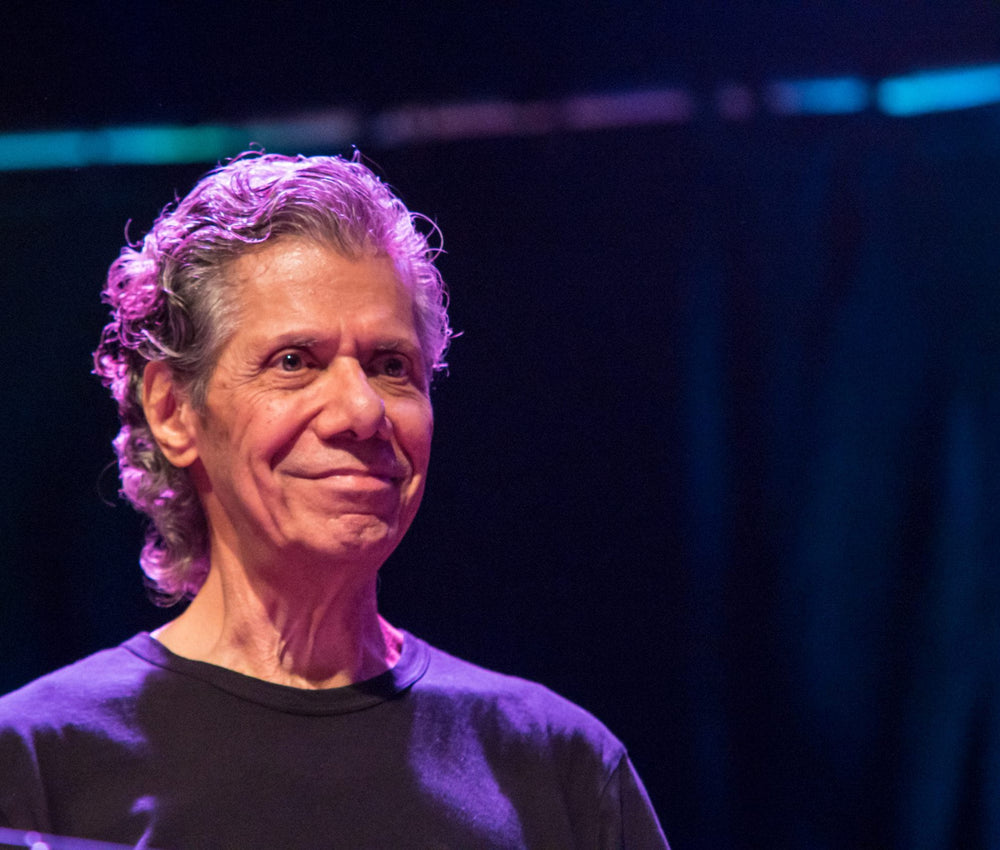

Dr. Patrick Gleeson: The Interview

Musician, Engineer, Producer, Professor of 18th Century English Literature?!

You may not be familiar with the name Patrick Gleeson, but he has quite a résumé. He ditched a career as a college instructor to become an electronic music pioneer in the late 1960s and 1970s. He created a synthesized version of Gustav Holst’s The Planets that was nominated for a Grammy, composed soundtrack music for television and independent films, ran a recording studio in San Francisco (Different Fur Trading Company), and was a member of Herbie Hancock’s band. Gleeson also recorded synthesizer performances of Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons and the music from Star Wars, along with collaborations with other jazz and electronic music artists.

Rich Isaacs: You didn’t start out as a professional musician, so where and in what field did you get your degree?

Patrick Gleeson: I got my PhD in 18th Century English Literature. I did my course work at UC Berkeley and my dissertation under a man at the University of Washington who I wanted to work with. Unfortunately, the 18th century guy at that time at UC Berkeley was everything I hated: a conservative, so forth and so on. And the guy at Washington was really brilliant, and also he had a wonderful attitude toward higher learning, which got me my PhD in a hurry. He became my thesis advisor. He asked, “so how long are you planning to spend writing this dissertation?” I thought he probably wanted to hear something like two years, but I wanted to be out of there in a year if I could. So I said, “maybe a year?” He just shook his head. I said, “longer?” And he said, “no, shorter. Much shorter.” And I said, “well, what are you thinking about?” He said, “why don’t you aim for 30 days?” So I wrote my thesis in 33 days, and I got an offer to publish the damn thing.

After a year at the University of Victoria, I began teaching at San Francisco State University. Then there was a huge turning point: I got very involved politically at San Francisco State. I was on the losing side of things – that was when S.I. Hayakawa became our president, there was a lot of turmoil and demonstrations, and I was sitting in with the students and committing numerous other transgressions. This prompted a tenure hearing on me.

It wasn’t really until probably 1966 that I just became so interested in electronic music that I wanted to make my own. And I was listening to Bartok’s first violin concerto, released posthumously. One night, I’d smoked some grass or maybe had a little acid, I can’t remember which – it was the ‘60s – and I listened to this and it just tore through me like a tornado. I thought, “my god, what am I doing with my life? This is not right. I’m not doing what I want to do. I want to make music like this” – a grandiose ambition. But I think the only way you succeed in the arts is by having grandiose ambitions. So with that, I was on my way out. By that time, the tenure hearing had started, and it was so political. I went home for Christmas vacation in 1967 and didn’t even return to clear my desk out.

RI: What was your musical background? (answer from www.patrickgleesonmusic.com by permission)

PG: I began piano lessons at six. By the third grade, jazz had hit me hard. I started playing out of Mary Lou Williams’ jazz piano books. After school, my best friend Jeff and I would listen to jazz records in his parents’ den – Art Tatum, Benny Goodman, Teddy Wilson, Lionel Hampton and the rest.

When I was practicing, I’d change the music to make it sound more like jazz. Mom caught on and she’d yell from the kitchen, “Doesn’t sound like your lesson, Pat!” We didn’t know this was called improvising.

A hip cousin, Mary Gleeson, was dating Norm Bobrow, a jazz musician and DJ for Seattle’s “race music” station. When I was thirteen, they set up this meeting between me and Ernestine Anderson’s accompanist, a local piano player whose playing I adored. Mary asked him if he ever accepted students. The guy looked at me and said, “why don’t you fall by the pad and let’s see what happens.” Fall by the pad? My god!

I ran home to tell my mother, who wasn’t exactly thrilled. For this Irish immigrant couple that had planned on me being a doctor, this seemed…umm, risky. Mom told me that if my regular piano teacher approved, I could take jazz piano lessons in addition to my regular lessons. Unfortunately, that teacher, whom I disliked anyway, decided this wouldn’t do. My parents agreed. I was devastated and quit music for 15 years.

RI: Getting back to electronic music, you’ve progressed through synthesizers from the early Buchla and Moogs to the Emu and Synclavier and beyond. What are you currently using?

PG: From the time that MIDI became available, I really transitioned out of big keyboards. So at this point, I’m entirely in the box [computer]. I’ve got a laptop and software (Ableton Live). And I don’t have any hardware at all.

RI: I assume there’s a keyboard hooked up to the laptop?

PG: Yeah.

RI: But the sounds are all in the software now?

PG: Yes. My experience has been so different from the young guys. For them, I can see the romance of these early synthesizers and why they love them so much. Younger guys call me up all the time and say, “guess what, man? I just copped a Moog! Wanna come over and see it?” “Well, um, not so much.” Really, when I think back on it, what I was doing when I was with Herbie was just terrifying. To go out there with six incredible jazz musicians – arguably some of the best in the world – with an instrument that played one note at a time, was not touch-sensitive, had no patch memory, and the entire set was improvised… I’ll tell you a funny story about that. When Herbie called me up after I’d done work on his album and said he wanted me to join the group, I thought, “how am I going to work this?” Thank god for the ARP 2600, which had just been released. So I thought, I know I’m going to have to change patches quickly, so I’ll color-code the patches. I’ll have this little rack right alongside my keyboard that all the patch cords will be hanging from by color. Then I’ll just keep track of that and plug them in. Well, forget that! I never even had the time to look over at this collection of patch chords. I just grabbed the nearest one. I think after about the third week, I got rid of everything but one color that was the longest, and just went with that.

RI: I can see how that would be terrifying.

PG: It really was! And the first night I played live with them – just to emphasize the jeopardy of it – the other guys in the band (Billy Hart, Eddie Henderson, Bennie Maupin, Julian Priester, and Buster Williams) were not enthusiastic about having me in the band at all. It was racial, cultural, professional, and regarding synthesizers, “this isn’t even music.” Despite the initial wariness, they have since become lifelong friends.

RI: But it probably seemed like a bit of elitism, too, didn’t it?

PG: That is a part (of it). You figure these guys – after I was out on the road with them for a year, I wondered how were they as nice to me when I first joined as they were when I thought of all the sh*t they would take every goddamn week from white guys. And I was brought to the band – in their view — by the white record producers.

RI: Tell me how you came to join the band. (answer from www.patrickgleesonmusic.com by permission)

PG: At Different Fur, after the last recording session of the day, I’d go into the studio and work late into the night on a synthesizer orchestration I was improvising over Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. It sounded incredible, I told David Rubinson, San Francisco’s one big-time producer. When he signed Herbie Hancock I began badgering David about letting me play on Herbie’s then-new record.

David told Herbie, “look the guy’s not a musician of your caliber, but he’s good with synths – maybe he can set up some patches for you.”

Herbie and I met at Different Fur. He’d brought one side of what would become Crossings, the breakout recording for Herbie’s Mwandishi band. We put on the tape and began listening to “Water Torture.” About 30 seconds in, Herbie said, “maybe add something here.” I began patching the Moog as fast as I could, afraid Herbie wouldn’t be impressed and would walk out. Soon, I had a sound like a flock of birds ascending into the music. I said, “you could try that.” “You didn’t record it?” Herbie said. “Well, no, I thought you’d play it.” He added: “You’re fine: record it.”

We continued this process, working our way through the tune. After an hour or so, Herbie said, “Look, I’ll come back tomorrow. Keep going.”

I stayed up all night and by the time Herbie returned I’d overdubbed one side of the album. Later, he told several music magazines that the experience had blown his mind – he’d never heard anything like it. A few months later, I’d joined Herbie’s band and was on the road.

RI: How did it happen, and how exciting was it to have Wendy Carlos contribute liner notes for Beyond the Sun?

PG: That was such a wonderful surprise. I’m not sure who asked whom first. She, at the time, was sharing a brownstone in New York with her producer, Rachel Elkind, so Rachel began corresponding with me. She was very tentative at first, and said, “I need to ask you, are you aware of Wendy’s fairly radical medical change?” or something like that. Wendy had addressed me up to that point as “W. Carlos.” I said, “Sure. I think that’s great.” She had just wanted to make sure that was no issue. When we went back to New York, we had lunch with Wendy and Rachel and then went over to Wendy’s studio, and she showed us what she was doing, which was just fascinating.

In retrospect, I really think that the only person who ever really nailed the arrangement of classical music on a synthesizer was Wendy. I don’t think I nailed it, and I don’t think anybody else did. I never heard anybody do it. It seems like, in a way, that it’s a very simple thing to do. But it isn’t just the technology, that’s almost the least of it. Wendy was peculiarly well-suited for doing that. When you would meet her, you were aware that she was very, very different, obsessive in a certain way. She would travel all around the world to see eclipses – that was a big passion of hers. And, of course, doing synthesizer music, the way she did it at that time, you had to be fairly obsessive. She brought this peculiar obsessiveness to it, but also maybe because she was kind of outside the mainstream sociologically, once she had gone through her surgery. She had a very independent streak and take on almost everything, and I think that extended to the Bach music she was doing.

I think, in a way, she just took it with the right degree of seriousness. I think I was too serious. And also, I was influenced by German prog stuff and liked “metronomic” stuff (I still do), but that approach is not particularly well suited for synthesized classical music – you really need to have ritardandos and accelerandos, etc. And my performance doesn’t really have those. So at the time, I thought [her stuff] was just wonderful. Wendy commented that that was the only area where she wasn’t totally in agreement with what I was doing. She said we’d have an interesting discussion of that at some point. If we were to have that discussion now, I would say, no, you were completely right, I was wrong. I think she was the only one who respected the music enough to really explore its essential nature, and at the same time didn’t take it so seriously that she didn’t realize that what she was doing was essentially a popular performance and the first thing it needed to do was to please. I think Tomita obviously pleased people – sold a lot of records – but didn’t particularly respect the music. And Wendy’s recordings did both. And I think my performance respected the music, and just was not enough fun. I just wish, if I were going back to do that now, I would do The Planets so differently.

RI: Interesting. In my opinion, yours is by far a more serious work than Tomita’s. I’ve always thought it was a shame that the timing of its release put you in direct competition with Tomita, who was coming off a hit with his synthesized Debussy album, Snowflakes are Dancing. Whenever I’ve told people about your album versus Tomita’s, I’ve said, “Patrick is an artist; Tomita is a cartoonist.”

PG: It’s too bad he died relatively early in life. When I did Beyond the Sun, I did so on spec. There was nobody saying “we’re going to release this album.” Most everything significant I’ve done, I’ve done that way. I sent it first to RCA and I got this strange letter back. After some very complimentary language about the album, the guy said, “Unfortunately, we have already committed to a synthesizer rendition of the same music by Tomita,” which was the first time I’d heard the name Tomita. That was the first complication. So RCA was off the table, and I went with Mercury Classics, which was a division of Polygram at the time. I would’ve preferred to have been on RCA. Mercury was well-meaning but sort of lead-footed, and they, in general, really didn’t get it. They were nice people, but as I say, not the most adroit. The second interesting thing that happened was they needed to get permission to release the album from the Holst estate, and the heiress to the estate, Imogen Holst, was a well-known British conductor. And she abhorred the idea in the extreme and turned it down totally and immediately.

RI: Just the concept in general?

PG: Yeah, just period. Maybe she hated my version, undoubtedly she did, but she also hated just the very idea of it all. So at that point, Mercury or Polygram’s lawyers – whoever the lawyers were — wrote and reminded her that the Canadian branch of her publishing company had already extended that permission to Tomita, and that it would be construed as prejudicial and discriminatory if they then refused the same thing to me. So her lawyers advised her to let it go. But she didn’t want either one released, which I think is a classic instance of taking life too seriously. Because it’s popular music to begin with, in a way.

RI: Back to keyboards. If you had to go back to playing a self-contained synthesizer keyboard, what would you choose?

PG: I’m so out of that loop, I don’t think I’m competent to say.

RI: How about of the ones you’ve used? Do you think you could go back to self-contained synthesizers/keyboards?

PG: I wouldn’t want to use any of them. I think there are some big expensive combo keyboards like the new $10K Moog, for example – the Moog Matrix One. Something like that would probably be what I’d use, but I wouldn’t be very happy with it. The very problem with having a synthesizer that’s not virtual and configured so that it’s programmable in this modern way means it’s not very versatile. You can’t jump into any patch point and initiate something that’s never been done before. The designers of the instruments have to have preplanned that. And often they do, to a considerable degree, but then what you have is a very complicated instrument that is not immediately accessible. And with Ableton, I probably have a shameful number of apps – probably 200 or 300 different synth programs of one kind or another. In a given piece of music, I might use 40 or 50 of them.

End of Part One.

(In part two we’ll learn how Different Fur got its name, along with more stories of performing with Herbie Hancock and others.)

Header image of ARP 2600 synthesizer courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Daniel Spils.

A Conversation With Mark O’Brien of Rogue Audio

Rogue Audio manufactures a wide range of tube, solid-state and hybrid audio components including integrated amplifiers, preamplifiers, power amps, phono stages and headphone amps. Located in Brodheadsville, Pennsylvania, the company states that its engineering goals include superior sonics, high quality and reliability, appealing design and high value. We spoke with Mark O’Brien, president and general manager of Rogue Audio.

Don Lindich: Please tell us a little more about yourself. Where are you from and how did you become an audiophile?

Mark O’Brien: I’m originally from New Jersey but have lived most of my life here in Pennsylvania. As a kid I was fascinated by electronics and started messing around with speaker design in my early teens. Being interested in both electronics and acoustics, I studied physics in college and earned my BS from California Polytechnic State University. I took some further grad school courses in physics but wound up getting an MBA so that I could better understand how to run a successful business.

Mark O’Brien of Rogue Audio.

DL: When and where did you launch Rogue Audio, and how did you get your start?

MO: I became really interested in amplifier design while I was working at Bell Laboratories in the early nineties. I was fortunate because I was working with some really bright electrical engineering PhDs who were a never ending source of both information and inspiration. At the time, the amplifiers and preamplifiers I built were all for my own use. The early versions were pretty crude but after a while, I started getting some really pleasing results. Eventually I convinced two of my colleagues to jump ship with me and start Rogue Audio in 1996.

DL: Where are your products made now? Are any Rogue products made overseas?

MO: All of our products have always been hand built here in Pennsylvania. We also locally source most of the parts we use to build them. A couple of years ago we built a brand new factory from the ground-up in Brodheadsville. It was a really nice step up from the old industrial building we had been working in for the previous twenty years (think air conditioning!) Rogue Audio has always had a great work environment in terms of our company culture and the people who work here. I would never want to change that.

DL: What is your design process and philosophy?

MO: I would say that our overarching design philosophy is to create great-performing audio products at attainable prices. That doesn’t mean that they are inexpensive, but rather that we offer excellent value. From an engineering standpoint, we design our products to be reliable, work properly with other well-designed products, and most importantly, to remain faithful to the original audio signal. We don’t try to “flavor” our sound by using components that artificially alter the signal. We also design our products to have low output impedances and high input impedances so they will work well with other solid-state or tube brands.

DL: Looking at your product line, Rogue components use various combinations of tube and solid-state electronics in their designs, and some novel applications of Class D amplifier technology. Is there any combination of these technologies that is your favorite or that you think leads to the best overall sound?

MO: That’s a great question. While we are primarily a tube amp company, almost all of our products incorporate solid-state devices in their design to one degree or another. In the case of our hybrid products, we have taken advantage of the best of both technologies. We use a proprietary technology we call TubeD that forces the solid-state devices to sound (and test!) like large high-performance tube amps. Essentially TubeD employs a small amount of feedback from the tubes to create tube-like behavior in the Class D output modules.

We were all very proud when The Absolute Sound chose our new DragoN amp, which is a hybrid tube/Class D design, as a 2020 Solid-State Power Amplifier of the Year. Our hybrid products are perfect for people who want tube sound without having any tube maintenance.

Magnum preamplifier.

Personally, I really enjoy designing in both spheres as well as writing the software to operate the products. Many companies have their embedded engineering (the software) written by outside companies. We bit the bullet several years ago and brought that technology in-house. All of the software we use to control the displays, the remote control operation, the input switching et cetera is all developed at Rogue Audio. This gives us the luxury of super-fast turnaround when we want to make any changes.

DL: What tubes do you use and how do you choose them?

MO: Our primary considerations are sound and reliability. For the small-signal tubes (used in the preamps and input stages of power amps) we mainly use 12AU7 and 12AX7 tubes because they are readily available and work great for audio applications. For the larger output tubes in our power amps, we use the KT120 tube. It sounds excellent and has proven to be extremely reliable. One of the fun aspects of tube amplification is being able to fine-tune the sound by swapping out different tubes. As a manufacturer we need to use tubes that are currently in production, but the end user has loads of choices in terms of what they can use in their gear – the world is truly their oyster.

DL: What are your most popular products?

MO: Needless to say, we sell more $3,000 Cronus Magnum III integrated amplifiers than we do $15,000 Apollo Dark monoblock amps but on the whole, our products are pretty popular across the board. I believe that they all offer terrific sound and meet a wide variety of needs.

DL: Who is your target customer, and what are the reasons they should buy a Rogue Audio product compared to other choices on the market?

One of several listening rooms at Rogue Audio.

MO: Our target customers are critical listeners who are not only passionate about their music but are also intelligent buyers. They recognize that our products not only sound great but are a good long-term investment in their audio systems.

DL: Your products are what most audiophiles would consider “affordable high-end.” Do you ever see Rogue expanding into the mass market, or conversely, into the more expensive and esoteric ultra-high-end market?

MO: No and no. I view our employees as craftspeople rather than assemblers. For example, the people who hand-solder our circuit boards do so at what I would consider an artisanal level. It takes several months to train someone to [even] begin to solder boards at the level we expect and a year or more to fully come up to speed. The same holds true for all of the other positions here. This level of craftsmanship pretty much precludes the possibility of mass-market production. As far as more esoteric products are concerned, it simply isn’t who we are as a company. I view most of the super-expensive gear as electronic jewelry more than hi-fi gear. Much of the pricing seems to be arbitrary or a result of costs that don’t really have anything to do with performance.

Adeline of Rogue Audio is adept at the fine art of soldering.

DL: What is the origin of your logo?

MO: I have always been a bird lover and the raven is a highly intelligent bird that doesn’t necessarily go with the flock. When we started Rogue Audio we saw that as symbolic of our company and our goals. That still holds true, but now has also become symbolic of our terrific customers.

DL: Anything else you would like to add?

MO: Only that I feel truly gifted to be able to do such interesting work alongside great people and within a really fun industry.

The factory in Brodheadsville, Pennsylvania.

All images courtesy of Rogue Audio.

Superposition: Getting Speaker Placement Right

In Issue 130, Russ noted that he’s been reappraising his audio system and went over some basic ideas about speaker setup. The series continues here.

When placing your speakers in any given room, you may initially be concerned with all the factors you can’t control: the size of the room, its orientation, what furniture must go in there, if there is a hard wooden floor or large exposed glass surfaces that will cause unwanted sonic reflections, and so on. Although each of these individual issues can be examined and dealt with separately, let’s look at one of the factors we can readily control, so that we can happily say, “I’ve found a super position for my speakers! They sound great here.”

In quantum mechanics, particles can be in two or more states at the same time. (I wish I could work and sleep at the same time! Wouldn’t that be cool?) This is known as superposition. “But what has this got to do with our speaker positioning?” I hear you holler.

It may not be a precise analogy but if our speakers are placed optimally, they can be in two “states” at the same time: occupying the physical locations where we set them down, and at the same time, sonically “disappear.” Like our subatomic particles, they could be thought of as having two states or properties.

How do we get our speakers to be both “there” and “not there?”

When we get the soundstage correct, we can look and still know where the speakers are, but according to our ears, the sound produced will seem as if the speakers aren’t even there. Instead, we hear the band or artists as an event, and are immersed in the performance. The speakers become exciting.

By making fine adjustments we can perhaps even suspend disbelief entirely.

So how can we improve our listening experience? What I’m going to suggest is a bit different from the usual setup articles. First, a tip on what to listen for.

Do you close your eyes when you listen to music? Depriving yourself of sight may enhance your sense of hearing and listening. As you listen, think about how significant the vocals are in the mix, and how the song may have been produced with the intention of drawing you in as the listener, by getting you to engage with the emotion of the piece.

Close your eyes and these Magneplanar 3.7i speakers will disappear into a seamless sonic presentation. Courtesy of Magnepan.

Now consider the fact that vocals are one of our first natural references for communicating, and using our own voice can help us in setting up our speakers.

You are likely most familiar with the sound of your own voice, and its natural properties are firmly imprinted in your mind. You know what you sound like. This can assist you in determining how far from the rear wall you should place your main speakers. If you stand with your back against that wall and speak out loud at normal talking volume, pay attention to the tone of your voice. You may notice more reverb and/or delay than usual. Your voice may sound closed and less open. Move slightly forward away from the wall and repeat your recital. Again, notice if there’s a change in your voice. Does it sound less “slappy,” slightly warmer and less echoey? Keep gradually advancing forward until you like the tone of your voice, where it sounds most natural and familiar to you without that excessive reverb and hardness from being too close to the walls. Then, try placing your speakers at this same distance from the wall and listen to their tonal balance, and make further adjustments from there. You’ll likely notice they also sound more natural and develop more openness and breadth in their tone; literally sounding less hard and closed-in. They say that talking to yourself is the first sign of madness but perhaps it’s worth it in this case!

In the previous article I mentioned the importance of reading the manufacturers’ guidelines for speaker placement, both in relation to their distance from each other and from the back wall. (Remember, these are guidelines, not absolute requirements.) But what if there is no such information? Many manufacturers will not state a specific optimal distance from the rear wall, because this can vary according to the dimensions of the room itself. The room will heavily dictate the overall sound, because its dimensions will determine the areas of bass reinforcement and cancellation and the behaviour of standing waves in the room. If you place the speakers in an area of cancellation or reinforcement, the tonal balance can suffer greatly.

You may discover that a good starting point for your main speakers is to place them one fifth of the total room length into the room and one fifth in from the side walls. Alternatively, you can try the famous “rule of thirds” you’ve probably heard of before. If that’s not possible, try placing them one fifth of the room away from the side walls. Measure your distances from the front and center of the speaker as this is the acoustic source of your sound. If you measure from the rear of the speaker you could end up placing them further into the room than is necessary. Save yourself some space – measure from the front. Also, measure precisely – it’s important to get the speakers as accurately and symmetrically placed as possible. Even fractions of an inch can make a difference.

Placing the speakers as far apart from each other as possible will allow for a wide soundstage. However, if they’re too far apart you’ll get a “hole in the middle” rather than a seamless spread of sound with a focused center image, which is what you want. To get your sweet spot, angle the speakers in toward your listening position, which will increase the focus of the image, making it more solid. Toeing in your speakers increases the ratio of direct to reflected sound. Check for increased brightness and adjust to taste as you make these incremental adjustments.

Here’s a suggested speaker setup starting point, from Audiophile’s Guide: The Stereo by Paul McGowan. Illustration by James Whitworth.

Be aware though that some speakers are specifically designed to be positioned without any toe in, as their responses are very even both on and widely off axis. This is great for consistency of sound in a wider seating area and toeing in these speakers may yield no improvement at all. Some speakers actually sound better with no toe in purely as a characteristic of their “personality” and may well be bright enough already.

If the sound is still too boomy, it may be that your speakers are still too close to the wall. Gradually bring the speakers away from the walls until that boominess is gone. Also, the depth of the sound field can suffer if the speakers are too close to the wall, and moving them further out into the room can really get the sound to open up.

Similarly, a good starting position for your listening chair is about one fifth of the length of the room in from the rear wall because, again, you won’t be located typically where standing waves peaks and troughs occur. Again, experiment. Moving the chair even a few inches forward or back can have a big effect. I realize that for many of us, however, we simply don’t have the freedom to put our listening chair in the ideal spot, or we may just decide against it because we don’t like the way it looks. If you can, it’s good to give yourself a reference of how good it sounds there and then you can aim for this within the compromises or further decisions you make afterwards. But at the least, try moving the listening position to different places, if at all possible.

What else can you try? Given that you want to avoid sitting where standing waves build up, you can experiment with placing your seating at a point that is not in a location where this problem is compounded, such as in the middle of the room. Measure the width of the wall behind your front speakers. Multiply this by 1.25 and place your seating this far back from that wall, in the middle of the room’s width. So, let’s say your room is 12 feet wide. Take your 12 feet width and multiply it by 1.25 = 15 feet. Place your chair at 15 feet from the rear wall behind the speakers and test drive your music from here.

But what if you find yourself competing with furniture or general access through the room? If this is the case, you may choose to reduce the distance between your main speakers so that your seat can be placed equidistant from them in a simple equilateral triangle. (In fact, many speaker setup articles will recommend such a triangle configuration between you and the speakers as a starting point, and it’s a tried-and-true method for many listening situations.) You may compromise some of the spaciousness of the soundstage – but not necessarily – as you place yourself in a more intimate position closer to the speakers. If you find this to be too focussed and direct sounding, experiment with toeing your speakers out a few degrees for your personalised room super position.

We think they’ve got it! From Audiophile’s Guide: The Stereo by Paul McGowan. Illustration by James Whitworth.

Header image: Klipsch Forte IV loudspeakers.

Analog vs. Digital: An Unending Debate

One of the most controversial topics in the audiophile universe is the digital versus analog debate. After the introduction of the compact disc in the early 1980s, the sales of analog music formats (LPs and cassette tapes mainly) declined steadily until 2007, when there was a revival of interest in vinyl. Since then, the market for vinyl LPs has seen a double-digit percentage rise each year, whereas CDs are gradually being replaced by music streaming, such that the value of LPs sold in 2020 exceeded that of CDs for the first time since the 1980s. Even the compact cassette tape is making a comeback, with the recent resumption of blank tape manufacturing.

There are several reasons for the revival of vinyl LPs. While some audiophiles claim that LPs sound better than digital formats, sales growth is being driven not by audiophiles (who only represent a small fraction of the record buying public and are mostly more mature adults), but by young music lovers getting into the format for the first time. Music has become a commodity, something that is so easily available from streaming sites, and this allows music lovers to acquaint themselves with music from years past. My son listens pretty much to the same music as I did at his age; he is no longer confined to what is on the charts. He can explore and decide for himself what he likes. The revival of interest in the music of times past also stirs up the desire to own the music in the formats that people used to have in that era. I can still remember the thrill of opening a copy of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon that I bought with the money I earned at my summer job. There is no such thrill when I click a song to play on Tidal. The whole package, with the illustrated jacket, the black disc, the printed lyrics and posters instill a pride of ownership. As audiophiles, we should thank these consumers for giving a reason to the record companies to continue manufacturing vinyl LPs.

This reissue of Stravinsky’s Firebird from the Mercury Living Presence catalog, done by Classic Records (now part of Analogue Productions) is one of the best LP reissues I have experienced. In fact, in terms of sound quality, it is probably one of the best classical LPs ever made. The dynamics on this LP are frightening. I am still looking for a good copy of this master tape. It was the combination of Robert Fine, the recording engineer, with his 3-microphone (Schoeps M201) technique and the recording venue (Watford Town Hall) that created this magic. https://www.stereophile.com/content/fine-art-mercury-living-presence-recordings

Going back to the question of which is better, digital or analog, this is not an easy question to answer and depends on the perspective of the user. If you ask a professional (recording and mastering engineers), you will probably hear a completely different answer than if you ask an audiophile. It is not so much due to the differences in how these two groups of users evaluate sound quality, but due to their very different experiences in using these two technologies. The experience of a typical audiophile is often limited to compact discs, SACDs, high-resolution PCM and DSD file playback, streaming, and vinyl LPs. For the professionals, it is the high-resolution formats (nobody records in Red Book format anymore) with the associated hardware and software, versus analog tape and the associated analog hardware. While audiophiles only care about the sound quality of the end product, professionals have to take into account the production process.

I am not a professional, but I have been making recordings for many years as a hobbyist, so I have some idea about the production process. Music production nowadays invariably involves multiple tracks, and digital technology has made this infinitely easier. All the mixing and editing can be done in post-production with a digital audio workstation and computer. A large variety of plug-ins are available to apply different effects to the sound. Expensive hardware is no longer necessary; there are plug-ins that emulate the sound of famous vintage microphones, plate reverbs, compressors and so on. And the changes made are fully reversible, whereas a bad splice of the analog master tape can become a disaster. It is like the difference between using a typewriter and Microsoft Office.

The danger is in relying too much on post-production and not paying enough attention during the recording process. During the early stereo era, sessions were recorded onto two or three-track tape recorders. Some companies such as Mercury only used three microphones, and the three tracks from the microphones were mixed down to stereo during mastering. Companies such as Decca that used multiple microphones would mix the tracks in real time into stereo during the recording session. This meant the balance engineers had to get everything right during the expensive recording sessions, as there was no way to remix the tracks afterwards. Microphone placement was of paramount importance. After the introduction of multitrack analog recorders, mixing could be done during post-production (and Dolby noise reduction, introduced in 1965, aided in the process). However, tape was (and still is) expensive and editing must be done manually (by cutting and splicing the actual tape!), giving the engineers the incentive to get everything right during the recording session. As my partners and I always record in analog (with digital as backup), we are well aware of these pitfalls.

The combination of Kenneth Wilkinson, the recording engineer for Decca, and Kingsway Hall as a recording venue is a guarantee for stupendous sound quality. The Decca Tree technique of using three omnidirectional microphones (Neumann M50) was developed by Wilkinson, Roy Wallace and Arthur Haddy. It is still widely used today for recording in large spaces. This reissue LP from Speakers Corner is excellent and comes very close to the master tape.

However, I have attended professional multi-miked recording sessions where one microphone was used for each player of an orchestra, placed casually and without regard for phase cancellation. The idea is that everything can be corrected during post-production, which is actually not true. The natural acoustics of the recording venue and the perspective of the orchestra can never be re-created by simply mixing the individual instruments together. This might be one of the reasons why recordings made 60 years ago still sound better than many modern recordings, despite the technological advances that have happened since then.

Old analog recordings often sound better because of how the music business is run today. In the past, large labels had their own recording teams with highly experienced recording and mastering engineers, along with an apprentice system to train the next generation. The engineers were intimately familiar with the recording venues and produced consistently excellent recordings. During the heyday of the music business, labels were able to make good profits from record sales. Nowadays, the revenue stream from sales of physical media has dried up, and the income from streaming is miniscule. Recording projects are often outsourced to the lowest bidder, and artists sometimes have to pay for the recordings themselves. Nobody can afford to take on projects such as Decca’s Wagner Ring cycle.

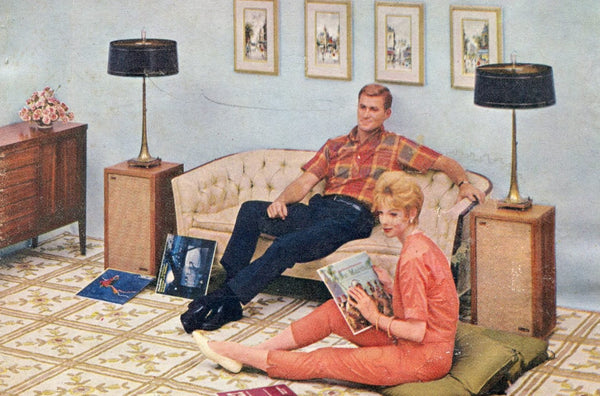

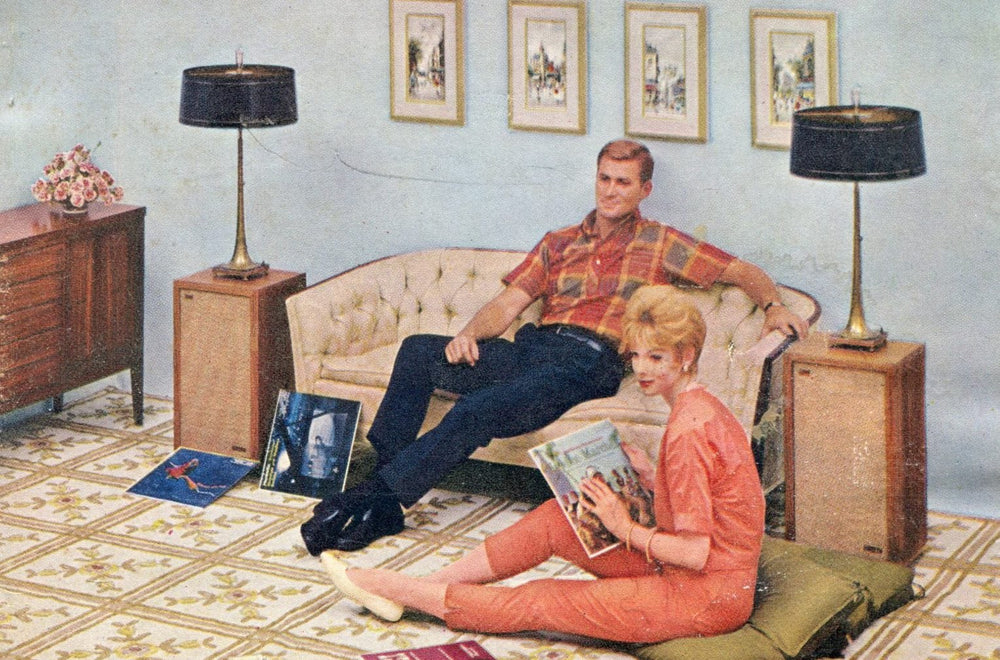

Another reason why early stereo recordings are often better is that the record-buying public in that era cared about sound quality. Buying a stereo system involved a significant financial outlay, and there was no distinction between “audiophile” and consumer equipment, at least not until the Japanese companies entered the market with mid-fi and mass market products in the 1960s and dominated it in the 1970s. In other words, anyone buying LPs or open reel tapes in those days was what we would now call an audiophile. All major classical labels were in effect audiophile labels, and sound quality was a major selling point, in addition to the quality and reputation of the artists.

Music nowadays is mostly played on smartphones, car sound systems and computer speakers. The number of people who still sit and listen in front of a stereo system is very small. Music is therefore mastered in such a way so as to optimize the quality when played through these modern means of listening. That means compression is used so that soft passages can be heard even in noisy environments outdoors or in a car, and equalization is used to compensate for the limited bandwidth of these devices. This obliterates the dynamic shading and tonality of the music when played through a high-quality stereo system.

This is not to say that there are no high-quality recordings being made nowadays. Many small independent labels still produce recordings with sound quality in mind, using the latest high-resolution digital technology. Ironically, some engineers feel that passing a digital recording through analog tape makes it sound more natural. This might have to do with the higher noise floor of analog tape. This noise mimics the background noise of natural acoustic environments, whereas the almost noise-free background of digital recordings actually sounds unnatural. There are now plug-ins that add tape noise, tape saturation and other analog artifacts to digital recordings!

Many people have offered opinions as to why digital recordings do not sound as good as analog in their estimation. As I have very limited technical knowledge of digital audio technology, I will not comment on the merits of these arguments. Through the monitoring system we use during recording sessions, switching from the live feed to high-resolution digital, especially DSD, sounds indistinguishable to me. However, during playback at home, the tape often sounds more dynamic and natural, but this could be due to the quality of the playback equipment, as I have not invested anywhere near the same amount on my digital front end as on my analog front end.

For the audiophile, comparing analog and digital often comes down to a comparison between LPs and CDs or high-resolution digital formats. Again, the quality of the respective playback equipment matters, and for LPs, proper set up of the record player is a must. The question is, do LPs represent the best analog has to offer? LPs have a lot of inherent limitations. The linear velocity of the groove decreases towards the center of an LP, and the lower velocity at the end of a side leads to an increase in distortion and makes tracking more difficult. For symphonic music, it is often the end of a piece that has the greatest dynamics, right where the groove velocity is the lowest. Compression (dynamic range limiting) is therefore often necessary to prevent mistracking. Longer pieces require narrower grooves to fit onto one side of an LP, which again can require compression.

The whole process of LP production involves multiple steps, with potential for sonic degradation at each stage. LPs that are made with new stampers sound better than those made with worn out stampers. Background noise is a function of the quality of the pressing process and of the vinyl material. An off-center spindle hole will cause pitch instability that is more evident with certain instruments such as a piano. Only when all the stars are aligned will one get a perfect record. Digital recordings, on the other hand, are always consistent. They sound the same whether you have played them once or a thousand times. Whereas music with limited bandwidth and dynamic range, such as a folk singer with a guitar, might sound better on an LP, a Mahler symphony will almost certainly sound more dynamic on high-resolution digital, given the superior signal to noise ratio and dynamic range of digital recordings compared to LPs.

There are around 60 recordings for which I have both the LP and a copy of the master tape (mostly copies of the production or safety masters). Most of these are Decca, EMI and RCA recordings from the late 1950s to mid-1970s. In no case is the LP superior. In over half, the quality gap is wide, and all the LPs that sound close to the tapes are modern reissues. Certain prominent magazine reviewers past and present have touted the superiority of first pressings, and some of these now cost an arm and a leg as a result. Examples include some RCA Living Stereo “Shaded Dog,” (Nipper, the RCA dog, is pictured against a shaded red background; later “Plain Dog” pressings have a plain red background), Mercury Living Presence and “wide-band” Decca LPs (so called because the silver band on the label that says “Full Frequency Stereophonic Sound” is wider).

An RCA Living Stereo “Shaded Dog” label.

In my experience, these old LPs rarely live up to their reputation, which I don’t find surprising. Vinyl record production technology has advanced by leaps and bounds since the late 1950s, so it would not make any sense that these ancient LPs should be better than those reissued today, unless the master tapes have significantly deteriorated. The original issues were also made in larger numbers, whereas modern audiophile reissues are made in far smaller quantities, with smaller production runs from each stamper to ensure more consistent quality. Rather than spending the money on these vintage collector’s items, why not spend the money on reissues to support today’s manufacturers and ensure they will continue to be available in the future?

Do LPs represent the best analog has to offer? Compare them to the original master tapes and you can decide.

So, here are my conclusions. Assuming the quality level of the playback equipment for digital and analog is comparable, I would go for a digital format if the original recording was in digital. It makes no sense to me to produce an LP from a digital source (except for DJs who use turntables for scratching). For music that was originally recorded in analog, the choice comes down to the type of music. For music that is large scale and dynamic, I would go for a high-resolution digital remastering as long as it was done correctly, in order to avoid problems associated with LPs such as end-of-side distortion, compression and noise. For other forms of music, it comes down to the quality of the LP pressings versus the quality of digital remastering. Given a choice, I prefer the DSD format. Other than any simple “splicing” or editing that might need to be done, DSD must be converted to PCM (usually in 24-bit, 352.8kHz, also called the Digital eXtreme Definition or DXD format) for editing before re-converting back to DSD. Whether this causes any appreciable loss in quality is debatable. For conversion of analog materials to DSD, it is best to do the remastering in analog domain before conversion.

Dealing with music originally recorded in Red Book CD standard (16-bit, 44.1kHz) is another matter. Early digital recordings suffer from a loss of low-level detail. In an article by a recording engineer about his early experiences with digital recording, he talked about the way he heard the steps of the recording artist as she entered the studio; on the analog tape, he could also hear the reverberation following each step, but on the digital recording played back at the same level, he could only hear the feet striking the floor but not the reverberations. This loss of low-level information is what makes early digital recordings sound unnatural and less dynamic when compared to analog tape. Early analog to digital converters had an effective bit depth of only 14 bits even though 16 bits were specified. This gave a dynamic range of 84 dB, and if overloaded would result in highly unpleasant non-harmonic distortions. The Nyquist limit (the highest frequency that could be encoded without aliasing, which is half of the sampling frequency) of 22 kHz is just at the limit of the audio band, thus requiring steep anti-alias filtering before digitization. These steep analog filters can introduce amplitude and phase non-linearities as well as ringing. The eventual adoption of oversampling allowed the use of more gentle filter slopes. Unfortunately, the loss of low level detail and the artifacts introduced by anti-alias filters cannot be undone during remastering. We therefore have a decade’s worth of recordings that will always remain problematic.

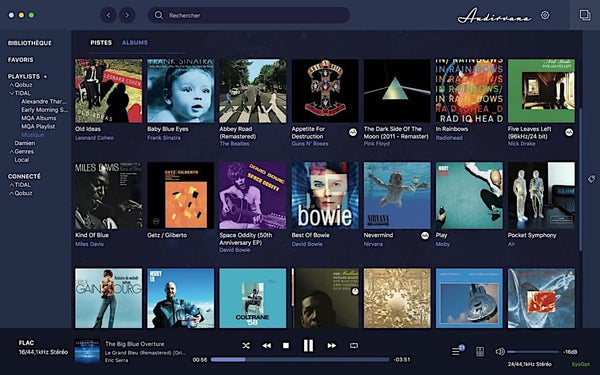

I have bought very few CDs over the years; most of my digital music collection comes from converting LPs and tapes to DSD, and from high-resolution downloads. For standard Red Book listening, either from CD rips or streaming services, I prefer real-time conversion to DSD128 during playback using Audirvana software.

There are many recordings made during the golden age of music performances, decades before the digital era, featuring artists such as Furtwangler, Walter, Kleiber, Callas, Oistrakh, Kogan, Du Pre, Cortot and Richter to name just a few. On the rock music front, most of the important releases from the Beatles, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Hendrix and other greats were made during the analog era, not to mention many classic jazz and blues recordings. Some of these have been remastered into new LP and digital releases, but we are at the mercy of the mastering engineers, since many of the original artists are no longer with us and cannot ensure that their original intent is properly preserved. This is why many people still seek out the original LPs. Some of these recordings are now being released in open reel tape format, mostly 1:1 copies from master tapes (copies made at the original playback speed rather than high-speed duplication, which is used for expediency but can create sonic degradation) and without additional manipulation. In my view, this is the ideal format for preserving recordings from the pre-digital era. I will further discuss this new trend in future articles.

Header image courtesy of Pexels/cottonbro.

Will A Perfect Audio System Ever Exist?

As a hard-core audiophile, I’ve spent the better part of my life working on improving my audio systems. I’ll admit – mostly because of selfishness. I want to hear music reproduced as perfectly as possible. I don’t want merely good. I want incredible, mind-blowing.

I’m extremely happy with the way my system sounds now, but I know it could be better.

Will we ever have audio systems that literally sound like the real thing? The obvious answer is no. After all, as Galen Gareis (see his articles in this issue and in Issue 130) has noted, you can’t beat the laws of physics. But what if you could, or at least work around them? Why not dream of the day when music systems can sound exactly like live music?

This is going to involve some pie-in-the-sky speculation and I invite readers to tell me I’m completely crazy, or laugh uproariously at my lack of scientific knowledge. But, we all want perfect audio reproduction. (Except for looking at mics, I’m going to skip over the fact that the recording chain would also have to achieve perfection.) How can we get it? Not only don’t I know the answers, I don’t even know if I’m asking the right questions. I’m putting this out there as food for thought, and to encourage comments.

The deviation from sonic reality starts right at the beginning of the recording process. As soon as the sound of the vocalist, instrument or whatever acoustic waves that are traveling through the air hits the microphone, it’s already game over. The microphone diaphragm has mass, and inertia. Objects at rest tend to stay at rest and objects in motion tend to stay in motion, whether a car or a microphone diaphragm. No matter how delicate the mic’s diaphragm, it can’t move in an exact reproduction of the sound hitting it.

The song doesn’t remain the same: as soon as the sound hits the mic, even an excellent one like this Neumann, it loses something.

So how do you solve that? Eliminate the mass! Create a massless microphone. In fact, there have been attempts at this, including plasma microphones and laser beamforming, where laser-induced (air) breakdown (LIB) generates an audio signal. Here’s a laser-and-smoke proof of concept microphone. This example doesn’t sound good, but it’s a prototype of a patented technology created years ago so who knows where it could lead?

At an AES convention once, I mentioned the idea of a massless microphone to the director of engineering of a well-known audio company. The person gave me a sharp look and replied, “we’ve actually got some ideas about that but if I told you, I’d have to kill you!”

The converse of the sound hitting the microphone is, of course, the sound coming out of the loudspeakers. Here the problem of overcoming mass and inertia is greater, since we’re dealing with the movement of much larger speaker diaphragms and voice coil assemblies. A partial solution that’s already been in use is the use of a servo control mechanism, where motional feedback from the driver is sent (from an accelerometer attached to the driver) back to the amplifier, which then corrects its output in an attempt to control the “overhang” of the driver. This typically would be used with woofers and subwoofers. However, I don’t know if it’s ever been tried with midrange drivers or tweeters. Anyone?

As another approach, maybe some kind of DSP that doesn’t actually measure the motional feedback from the drivers, but “anticipates” the drivers’ behavior might be worth looking into. Musical signals and driver behavior can be extremely complex, but maybe it’s just an engineering problem.

If we can dream of a massless diaphragm, why not a massless speaker? Actual massless speakers have in fact been demonstrated – dig this YouTube video featuring The Audiophiliac, Steve Guttenberg, and designer Nelson Pass of Pass Laboratories talking about his Ion Cloud speaker.

Nelson Pass and his Ion Cloud speaker on the cover of Stereophile, Volume 6, No. 1, 1983.

Those of you lucky enough to have heard an Ionovac tweeter can attest to its almost spooky purity. But so far, such designs have proven impractical or impossible to implement on a mass-market scale; as examples, the Ion Cloud produced high levels of ozone, and the legendary Hill Plasmatronics speaker had to be fueled with helium.

Interesting work is being done with carbon nanotube speakers, but they simply have less mass, not none, and the sound quality isn’t there. Yet. And at a CES a few years ago, someone demonstrated a system that involved beaming an audio signal on an ultrasonic carrier wave, or something like that, but I couldn’t attend the demo and don’t remember the company’s name. As I understand it, the system still needed a transducer to send the signal. Can any readers help?

Maybe there’s a way to manipulate air that no one’s thought of yet.

A pair of DuKane Ionovac plasma tweeters. If you’ve heard these, you know.

Let’s consider our music sources. In the case of analog, it involves dragging a rock (the stylus) through a plastic medium (the record), then sending a minuscule signal created by a cantilever and electromagnetic generator (the rest of the cartridge) to an equalization circuit (the phono preamp). I think it’s safe to say that such a system is never going to attain perfection. Analog tape seems no less odd when you really think about it – running a thin ribbon of plastic, coated with magnetically-responsive particles, through an electromagnetic tape head for recording and playback. On the other hand, like a bumblebee flying, it never ceases to amaze me at how such Rube Goldbergian devices can sound so utterly fantastic.

I can’t help but think: might there be an entirely new way to record and reproduce a perfect analog musical signal that doesn’t involve imperfect analog playback hardware? Some kind of as-yet-un-invented optical technology, maybe? I know, I know, there would be transduction involved in the acoustic-to-optical-to-electrical signal, but a man can dream, can’t he?

Then there’s digital. I’m not an engineer and don’t want to debate how much of a sample rate is really adequate (we can leave that for the comments), but the idea of chopping up the audio signal and reconstructing it just seems…weird to me. (I know, I know, and I’m not that much of a techno-rube, but…still.) I do find the sound of high-resolution audio to be satisfying and enjoyable. But is it the sonic perfection we’re looking for?

How about an audio system’s preamplifiers and amplifiers? Many of us are familiar with the concept of “straight wire with gain,” where the ideal amplification circuit would simply amplify the signal and add no coloration of its own. How could we make it happen, especially when veteran circuit designers and hobbyists know that not only can parts quality make a difference, but even the physical layout of the components on a board (because of RF susceptibility and other issues) can have a sonic impact?

The first thought might be to make a circuit (for other audio components, as well as preamps and amps) as simple as possible. Seems intuitive – simple circuits might yield greater sonic purity. But then, every part in the sonic “recipe” of the circuit becomes more critical! And when you get into the real world, the simpler-is-better analogy simply falls apart. My second thought is, make the actual product smaller. Minimize the distance between the internal components. OK, maybe not – just try to make a conventional power amp with inadequate output transformers and see how it performs. Although, the remarkably small size of Class D amplification circuitry is a tantalizing glimpse of what can be done. And, have we really explored the limits of what integrated circuit or passive component miniaturization might sound like?

An ICEPower 1000A Class D mono amp module. It measures about 4 inches square and puts out 1,000 watts.

Maybe digital signal processing (DSP) is the answer. In much the same manner that servo mechanisms can control the behavior of loudspeakers, and negative feedback can improve the sound in amplifiers, DSP can correct for all kinds of audio behavior, not the least of which is loudspeaker room-response correction. But perhaps other sonic areas could benefit in ways that no one’s thought of yet.

Speaking of the room, we encounter another major issue. The room the recording was made in won’t match the acoustics of your listening room – one will be overlaid on top of the other. How on Earth will that ever be overcome? Why do the initials “DSP” appear in my head yet again? It would be a daunting if not impossible task – how would we ever quantify the uncountable acoustic signatures of bazillions of recordings and figure out how to eliminate the acoustic effects of each person’s listening room? Call me the Man of La Mancha.

Back to a straight wire with gain. Wouldn’t cables literally be the closest manifestation of this? If only. Cables have resistance, capacitance and inductance as well as other variables like skin effect and (thank you again Galen) different velocity of propagation across the frequency band. Then there are the impedance mismatches between amplifier, cable and speaker, or between the electronics in the system (for example, the preamp and amplifier) to consider. How to eliminate all that? Are you thinking what I’m thinking? Wireless signal transmission. But then, you need to have transducers at the signal source and the playback device to convert the wireless signal back to an electrical one, and how much fidelity are you going to lose in the process? (And here you have an argument in favor of integrated amplifiers or all-in-one components that reduce the number of wired connections.) Still, the idea of a completely transparent wireless technology is intriguing.

Getting into the realm of science fiction, how about bypassing an audio system altogether with some kind of a direct neural implant? Cochlear implants are already a reality and research is ongoing, so who’s to say an implanted high-end audio system couldn’t be done someday? Of course, the first thing you’d have to listen to would be Steely Dan’s “Aja.” (Dan fans will get the reference.) Even better – the implant could include a direct brain interface with a streaming service, so all you’d have to do is think of a song and it would play. You could adjust the sound just by thinking, and have a soundstage as vast as the Grand Canyon if you wanted.

I’ve spent all this time considering the hardware. What about us, the actual people who are going to be listening to all this stuff? Could there be some way to put us into a state of mind or affect us in a way that makes our audio systems seem more “real”? I know what you’re thinking…but I don’t know if psychoactive drugs are gonna get you there. But seriously, could a drug be developed that gives us better hearing acuity? Or some kind of audio-enhancement hearing aid that lets us hear our systems with better fidelity?

One last thought. Many industry giants have worked to advance the field of high fidelity. Perhaps some great ideas have been lost, and are waiting to be rediscovered.

As Walt Disney once didn’t say, if you can dream it, you can do it.

Header image courtesy of Pixabay/Gerd Altmann.

![]()

Cable Design and the Speed of Sound, Part Two

In Part One of this series (Issue 130), Galen Gareis of ICONOCLAST cables and Belden Inc. began an extensive exploration into a critical but not often discussed aspect of cable design: the velocity of propagation (Vp) of audio signals. In this installment, he looks at practical ways to change the velocity of propagation and improve signal linearity for the benefit of better cable performance, and examine other subjects.

Also, introductory material on the subject by Galen and Gautam Raja is available in Copper Issues 48, 49 and 50.

What can we do with the insights into the fundamental ability to change the Vp with frequency we examined in the last installment? Can we do something to improve the signal linearity in audio cables?

Here is an example of what might happen in a cable that is designed to have varying levels of Vp differential based on managing the capacitance of the cable. We can do this by varying the size of the insulation, or even the insulation material. For simplicity, we’ll hold DCR the same to isolate the capacitance effects on Vp.

Notice that the change is well within the audio range, and the Vp change is pretty extreme on an absolute basis. (Short cable lengths can allow us to ignore Vp non-linearity; as a first approximation they are too short to have a meaningful propagation time difference.) What if we do not want to ignore this issue, but achieve a better balance in performance by manipulating other cable parameters? If our objective is to make cable better overall, why not? Well, better cable is far more complex and expensive to make, electromagnetically, I grant you that.

In the example above we look at only capacitance. But, inductance is loop area-determined. The farther apart the wires are from one another, which is known as the loop area, the lower their capacitance. But the equations for measuring inductance say that as inductance gets higher, the farther apart the wires are moved. What to do?

A cable’s capacitance can be designed in several ways. If we want to retain a low inductance, which keeps changes in the phase of a signal and its resultant frequency-response anomalies to lower levels, we need to keep the inductive loop area small. Initial phase alignment, the time alignment of signals applied to the cable, in audio cables is small, so many feel it can be ignored, as the initial time-aligned phase isn’t getting too much worse with the Vp speed differences across frequency. This is called group delay, or how much the best to worst signals separate going down a cable after the initial time alignment applied to the cable. A cable shouldn’t make frequency time alignment worse, but it does.

If we consider a square wave, we can get a better idea what group delay and phase delay are, since in order for a square wave to maintain its integrity, its frequency components have to be kept in proper phase alignment with one another.

http://www.iowahills.com/B1GroupDelay.html – A square wave is square only because its frequency components are in proper phase alignment with one another. If we pass a square wave through a device and expect it to remain square, then we need to ensure that the device doesn’t misalign these frequency components. A Group Delay measurement shows us how much a device causes these frequency components to become misaligned.

Keeping the signal in correct phase right from the start is imperative, but group delay, which is caused by the differential in the velocity of propagation, is how a cable makes things worse.

Our objective is to attain the best cable performance possible. How do we do that?

One way is to lower inductance and capacitance. Thicker insulation does not lower inductance; it increases loop area (the space between the wires), which as we have seen increases inductance. To keep the loop area as small as we can for low inductance, but not increase capacitance, we need to use the absolute most efficient dielectric(s) we can. Air is the best dielectric and Teflon is the best material. A low “E” or dielectric constant in an insulating material will allow two wires to be as close together as they can be and reach the lowest possible capacitance.

When E, the dielectric constant, is high, the capacitance is higher at a set RF impedance. We can use the capacitance value calculated at RF through the audio band because L and C are both fixed across frequencies. Only at RF is the Vp=1/SQRT(e). We test RF coaxial cable capacitance at 1 kHz for example.

The graph above shows how capacitance and the velocity of propagation are directly related to the dielectric constant for a 100-ohm RF cable type. The capacitance value can be used at audio frequencies, but not the dielectric’s RF velocity.

At RF;

Vp = (1/SQRT (dielectric constant)) or Vp = (1/SQRT (L*C))

L and C are constant from low frequencies through RF with a set dielectric material. We’ll look at this in more depth later in the article.

We certainly want to start with the lowest “E” value possible, and not just for its effect on capacitance alone. But in designing a cable, does capacitance have to be as low as possible and then we’re done? Not exactly.

The above equation for low-frequency Vp also has the variable, R (resistance). Resistance is almost always considered a “passive” element. It is thought to be responsible for attenuation only, like turning up and down a volume knob. However, it influences Vp non-linearity, too. Higher DCR flattens the Vp linearity through the audio band – but only if the DCR seen in each cable “circuit” is sufficiently isolated from other electrical paths. The data below shows what happens when resistance is varied, and we hold the capacitance to 15 pF/foot. And, do we even want zero R or C? And what happens if we ignore the Vp differential and lower the resistance as far as we can?

Vp ACROSS LOW FREQUENCY BY AWG

The chart and table above show that if we decrease the wire size, which increases resistance, we can also manage the Vp differential across the audio band. This allows us to use lower capacitance if, if, IF we can utilize higher DCR wire. Designs can use multiple smaller wires, but beware what happens to C and L when we use more aggregate wires to reach a low bulk DCR.

Physics says we can’t speed up the low frequencies, only slow down the higher frequencies. The curve flattens below 250 Hz. But to avoid too high of a capacitance in order to lower the Vp differential, we can also change just the wire DCR, which allows us to lower the capacitance. We balance the R and C.

Observations

Let’s look at a few things to better understand what is available to us in designing cable, and where these factors are working. R, resistance, isn’t stable with frequency, as a wire’s skin effect (its self-inductance, which is predominant at higher frequencies) and its proximity effect (inefficiency in passing current, which is predominant at lower frequencies) can cause attenuation that varies with the audio signal’s frequency.

The tables below on inductance and capacitance show a few cables’ response across frequency. They are close to a constant to the first approximation. Do we see this in audio cables?

Does the ICONOCLAST cable really show flat L and C, too? It does. The table below shows R, L and C measurements up to 1 MHz for an earlier design prototype. Notice that Rs (Resistance swept) increases as we go up in frequency. Why? Some of this is caused by skin effect and some is the result of closely-spaced conductor wires. Also, the proximity effect concentrates current flowing in the same directions near the wire surfaces nearest one another, and pushes the current away from the two closely-spaced wires in the that carry current in the reverse direction. Both of these factors superimpose to decrease wire efficiency (less current uniformity across the wires’ cross sections).

ICONOCLAST SPEAKER CABLE PROTOTYPE LUMP ( TOTAL VALUE)/

ADJUSTED TO FOOT ELECTRICALS

Higher frequencies, which don’t require much current, need a larger surface area, not the overall volume of wire, to propagate with low attenuation.

High-current applications need a larger wire volume for low attenuation at low frequencies.

If you have high current and high frequencies, you get a double whammy for attenuation. This kind of wire would be very inefficient.

This chart, which was shown earlier, shows that the impedance curve is non-linear and need three separate approximation equations to characterize three different regions of test performance. The low-frequency curve contains the imaginary component “j” times omega or v. Omega is equal to 2f. We saw this set of variables in the Vp equation at low frequencies too; Vp = SQRT (2v/R*C). Capacitance is directly related to; Vp = 1/ SQRT(E) at RF.

Why is increasing impedance through audio frequencies a problem? Below we see a graphic from one of Paul McGowan’s Daily Posts that shows the energy spectrum of typical music. (I have these types of graphs too, but Paul’s is better than mine!) If we want to match the power transfer of the cable to the musical spectrum we need to do it in the highest average power distribution spectrum we can within with a non-linear sweep distribution.

What cable needs to do is match the impedance where the most power is being distributed, or the power energy spectrum. Where is this region actually? It is below 500 Hz – and smack dab in the region where the impedance curve rises. This makes a true cable-to-low-impedance load match technically impossible to do. It is great to think about, but the physics says we can’t get there. Vp drops too much and too fast as frequency drops raising the impedance when we need to really have it lowered. At “zero” Hz Vp is by definition zero so we know we’re going to see a change with frequency.

TWEETER POWER,

AUGUST 31, 2020 by PAUL MCGOWAN

There is a near 1,000 watt peak at 60 Hz. The impedance of a cable can’t be close to 4 to 16 ohms in this region due to Vp non-linearity. It is impossible to do using low frequency open-short impedance tests. The physics says low-impedance measurements through the audio range can’t be done with reference open-short impedance measurements (except open-short is most close to how audio cables work, and need to be measured).

True, and honest impedance graphs of a speaker cable show this to be the case. Better cable can indeed decrease the low-end impedance rise, but not eliminate the physics we are working against that cause that impedance rise. The impedance and phase curves below exhibit proper open-short impedance measurements.

ICONOCLAST is a 0.08uH/foot and 45pF/foot 11.5 AWG aggregate design, all very good values for a complex design with 24 0.20” wires in each polarity, which serves to flatten the Vp curve and as we have seen, thus lower the impedance rise at low frequencies.

Below is what a typical ported-speaker impedance trace actually looks like. The solid line is impedance and the dashed line is phase. Superimpose this onto the above graph. This is the true situation we have to deal with, and illustrates how speaker cable really “matches” with a speaker. We can’t match “8-ohm” cable.

What do some other cables do at low frequencies? The chart below graphs several measured cables. If we look at good old POTS (Plain Old Telephone System)-type cable, we see that we can have cable that measures 600-ohms at 1 kHz! Yes, the dropping Vp differential low-frequency properties increase impedance to about 600 ohms. We’ve decreased that effect to just 270 ohms in ICONOCLAST speaker cable but 2-16 ohms is an impossibly low reality in a referenced open-short test. That’s because capacitive reactance, Xc=1/(2FC) keeps going up (resistance to AC electrical energy flow) as the Vp keeps going down (raising impedance even more).

In the next and final installment we’ll look at resistance, the effects of various dielectrics, wire geometry, skin effect and other considerations, and summarize our findings.

Talking With Nason Tackett of Hear Technologies

When it comes to comparing audio equipment like speakers or headphones, it is difficult to avoid biased opinions from manufacturers and designers, since it is inevitable that each one has formulated its business model based on an individual preference and an ideal concept.

With this in mind, it stands to reason that a company that makes amplifiers, consoles, or mixing systems might have a more neutral perspective about the types of devices that might be used with their equipment, and the various pros and cons of each,

Nason Tackett is the senior design engineer of Hear Technologies. The company has already made a reputation with Tackett’s cutting-edge monitor mixing units and recording interfaces, as well as other audio/video support devices. Hear offers tablet-sized mixing consoles that allow musicians and vocalists to customize their respective headphone mixes for recording in the studio or for live performance. Although small, these consoles can submix up to 128 channels with a frequency response of 20 Hz to 20 kHz and a sampling rate up to 192 kHz.

Nason graciously made time to share some insights about headphones, in-ear monitors (IEMs) and earbuds from the perspective of the company’s musician, producer and engineering clients, as well as looking at the gray zone that separaes audiophile and professional audio equipment.

John Seetoo: Owsley Stanley, best known for his audio R&D involvement with the Grateful Dead and (sound and musical instrument company) Alembic, held a philosophy that hi-fi home audio gear and pro audio gear should have negligible performance differences apart from the durability requirements of pro audio gear. This is an outlook shared by Pat Quilter of QSC Audio (Copper Issues 118, 119 and 120) and John Meyer of Meyer Sound (Copper Issues 99, 100 and 101).

Do you share or differ with this philosophy?

Another question: apart from mixing capabilities, in what ways does your design of the Hear Back mixing units for musicians differ from or are comparable to audiophile headphone DAC/amps?

Nason Tackett: I do share this philosophy. If I am designing equipment that will be used in the creation of music recordings, I want the accuracy to be at least as accurate if not more accurate than what someone will listen to the playback of the recording on, even if [they will be listening on] a very high-end system. You want to hear all the detail [as well as] all the ugly parts as you make the recording. You don’t want to cover them up and then have someone hear them during playback on a [home] hi-fi system.

The headphone monitoring systems that I have designed are very much like audiophile headphone DAC /amps. The goals in designing them were to be accurate, to avoid coloring the sound, and [to be] as low [in] noise as possible. I like to be able to turn up the master volume and have no hiss. Thankfully, I am in a situation where I’m able to design the best piece of gear I can without anyone telling me to cut corners or cut costs. I just do what it takes to make it the best that I can.

I ran my own live sound and recording company for over a decade, so while designing these products I brought my pair of near-field studio monitors in that I was familiar with, and used them to critically listen to every product I made. I trusted my ears as much as what the test equipment was showing me.

JS: While IEMs are the likely default listening platform for musicians using Hear Back PRO monitoring units in a live setting, headphones of all types probably would be deployed when used in the recording studio. Can you discuss a bit about the differences in headphone types that clients have been using, and any advice for optimal use? For example, would someone in the studio using AKG headphones have an easier time than someone using Dr. Dre Beats?

A Hear Back PRO mixer at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. Photo by Jessica Coleman.

A Hear Back PRO mixer at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. Photo by Jessica Coleman.NT: I will refer to headphones and IEMs (in-ear monitors) collectively as “phones.”

We see people using everything! There is no right answer to what someone should use. It depends on your needs. Some people think [that] using something that has a razor-flat frequency response is the right answer, but this is not necessarily true. Everyone’s hearing is different. People have hearing loss in different areas, so what works for one person might not for another. Your brain gets used to equipment [that] you use frequently.

People who spend the money to get a good-quality pair of IEMs molded to their ears often bring these into the studio to record with because they are used to the way they sound. And this makes good sense. If you don’t have phones [that] you are used to, I recommend visiting a trade show or a shop where you can try a lot of different types to [hear] for yourself. You will want to bring a recording that you are very familiar with and see if you can hear everything, especially the things you really need to hear to perform as a musician.