Our little world is categorized as “High-Performance Audio” (HPA) by the Consumer Technology Association, the group that puts on CES every year, and I think that’s a far better term than “high-end audio” (which brings to mind Richie Rich and lighting Cohibas with c-notes). For quite a few years now, we’ve kvetched about the reduced presence of HPA at CES, to the point where last year the audio exhibit floors at the Venetian shared space with the likes of Simmons Mattress and the AARP. Go on: make your own jokes. Trust me, those of us in the biz did.

Apparently, the cries of outrage were heard. This year, “our guys” were condensed down to only the 29th floor (with the exceptions of Bluebird Audio and Lamm, up in the high-roller suites on 35), BUT there were no irrelevant outliers as there were last year. Some of the exhibitors were obscure OEMs, but they were in audio…not bedding.

Before the show, the question on the minds of exhibitors, attendees, and press was, ” Mother of mercy, is this the end of Rico?”—or something like that. The rooms on 29 were largely booked—but would anyone come? And would there be HPA at CES in 2019?

As you probably know, CES is huge. I mean, really, truly immense. The majority of the gizmos and ooh-ahh products that you see on TV and on tech blogs from CES come out of exhibits at the Las Vegas Convention Center (LVCC), which is roughly the size of Rhode Island. Maybe Delaware. To go there is to become instantly, irretrievably lost in a bewildering maze of shiny products and even shinier spokesmodels. If you think sexism is dead, you’ve never been to CES. Or Las Vegas in general.

Far beneath the HPA world enshrined in the attic of the Venetian, in the subterranean bowels of the V, there are large ballrooms used by giant tech companies. Some of them have recognizable names, and some of them are multi-billion dollar monoliths you’ve never heard of until they’re bought by even larger nonentities. Those are not the places where you’ll find our stuff.

Those ballrooms and the other exhibit areas around the Venetian and the adjacent Sands exhibit hall draw thousands. If you had to wait on credentials in the V, this is what you faced:

Glad I got my badge before the show started!

Stepping off the elevator onto 29, this scene didn’t fill one with confidence….

…and my initial look around 29 on the first morning of the show seemed to bear out all the pessimist predictions, including my own:

Welcome to The Shining.

—But that’s unfair. It got busier. Lots busier:

The line for elevators to 29 and 35.

The central waiting area on 29 got to be like a pile of puppies.

Many on 29 were veteran CES exhibitors, like VTL, Kimber Kable, DeVore, Vandersteen, Genesis, Egglestonworks, Transparent, AudioQuest, Copper contributor Roy Hall’s Music Hall, and others. Old-school names reappeared: Technics, ESS, JVC, Kenwood. Relative newbies like GoldenEar and Emotiva had strong presences; both companies were founded by industry veterans (Sandy Gross and Dan Laufman, respectively). To get the full picture, the map of 29 can be found here.

The gloomy, rainy weather of the first day may have been responsible for the empty hallway shown in the second pic above. The unusual sight of a rainy Las Vegas looked like this from the Music Hall room:

I once admired the view from this room. Roy said, “It’s a waste of a perfectly good desert.”

Rich Vandersteen held court as usual, complete with trademark JCP plaid shirt.

Nagra had a lovely and lovely-sounding room with YG speakers.

Egglestonworks featured the Andra IIIs and big, blingy Triangle Art tables. And blinding sun.

In the midst of the big-boy megabuck systems was a new exhibitor from Sweden, Soundots. I was bemused by their demo, which featured their small, nicely-made $290 Bluetooth speaker…times 66! Each individual speaker can link up and attach to an unlimited number of others, which will then play in sync—and flash their colored LEDs in sync. So— that curved arc in the picture would sell for 66 x $290=$19,140?!? The gent demonstrating the set-up was so enthusiastic and chipper that I restrained Evil Bill and played nice.

Oohhh…light show!!

The ever-affable Chris Walker, Andrew Jones, and Kathleen Thomas from ELAC. Andrew was ill—so for once I stayed away from his demos, which are always informative and amusing. Oops. Anything to avoid a repeat of last year’s deadliest-ever CES crud.

I was happy to see Copper contributors Ken Kessler and Roy Hall, and exchange a few barbed comments.

Instead of his usual big speakers and stout Pass amps, Sandy Gross was showing only GoldenEar’s new Digital Aktiv stand-mount speaker, which runs on Chromecast. MSRP was guesstimated at $2k.

ESS’s day in the sun was back in the ’70s with the Heil-tweeter-equipped AMT-1. Rico Caudillo has revived the brand in recent years, and had a full range of speakers at CES.

Jonathan Valin seemed enraptured by the latest Magico-Constellation pairing. I didn’t disturb his reverie (this time).

Ruark, a UK company seldom-seen in the States, brought their lifestylish “High Fidelity Radiogram”.

Peter B. Noerbaek—the “PBN” of PBN Audio—showed two interesting projects in the Dayton Audio room: a turntable based upon an old Denon broadcast table, and an impressive and very dynamic speaker. Peter’s woodworking facilities are state-of-the-art.

Raidho had a typically-impressive demo system, with full Chord electronics. My only complaint was that they were afraid to play loudly enough….

No CES is complete without a Fremer-Kessler run-in. Leland Leard stands nearby, ready to intervene….

“Are you f*%$@*g KIDDING ME? How can you SAY that??”

Pro-Ject had an impressive and dramatically-lit (read: hard to photograph) room with a full range of products, not just the turntables for which they’re so well-known.

Egglestonworks speakers could be seen again in the VTL room. As usual, both presentation and sound-quality were absolutely stellar.

There’s no greater pro in the audio industry than veteran Stephen Baker. Stephen is now Lenbrook’s Senior Sales Director for the Americas; Lenbrook’s brands include NAD, Bluesound and PSB.

Continuing the outside-the-room motif: Dan Laufman of Emotiva. Dan had a full room of stuff, also.

Musical Surroundings again showed the spell-it-out display of Clearaudio turntables first seen at RMAF. Try as I might, I couldn’t include the “C”.

I’m always happy to see songbird Anne Bisson, and exchange cheek-pecks. Sorry she’s a bit blurry here, in the Genesis room. Besides Anne, there was some gear there from Genesis and Viola, and Gary and Carolyn Koh. I probably should have photographed them. Sorry.

There was more dramatic lighting in the Technics room, where they showed an updated SP-10 turntable, at an updated price: $10k or so.

As we reported recently in Industry News, the uncertain state of Classe’ was resolved by purchase of the company by Sound United—which had previously picked up the D+M brands earlier in 2017.

John DeVore’s room was a refuge of good music, as usual.

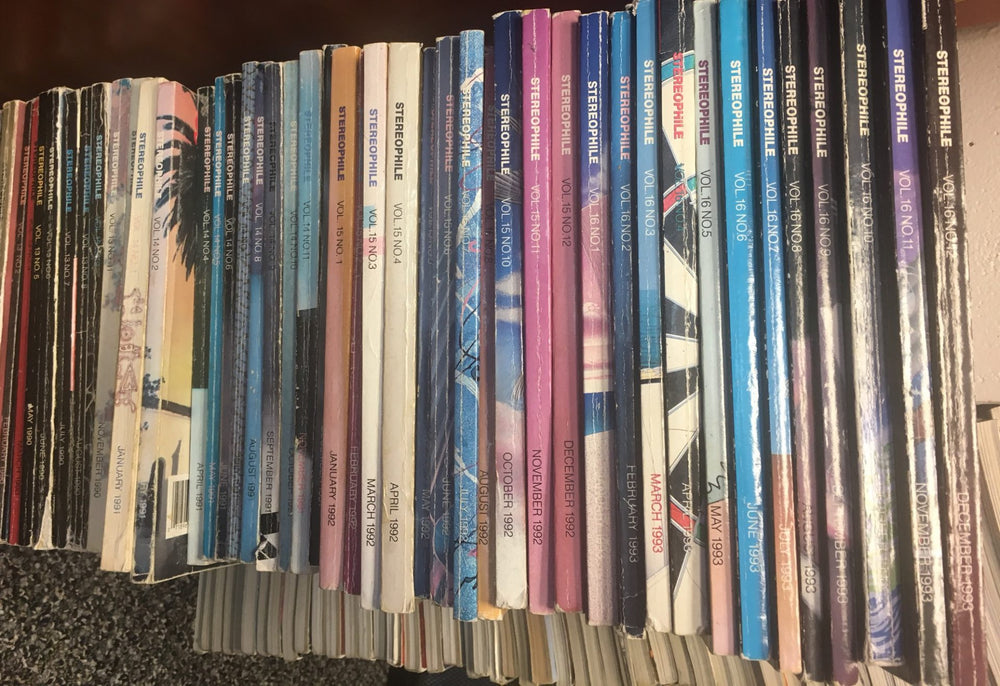

Industry veterans David Solomon and Charles Whitener chat with John Atkinson and Jana Dagdagan of Stereophile.

Escaping the Venetian means exiting through the absurd-but-impressive lobby…

…and passing the dramatic tower….

…and eventually reaching the endless expanse of the Las Vegas Convention Center (LVCC), as seen in the header pic. The grounds outside the buildings including everything from a bunch of drifting racers (I could hear them and smell the burning rubber, but never saw them), the delightfully- non-waterproof demo house from Google, the usual inflatable Gibson pavillion, amd a bewildering array more.

Not sure what it all is, but there’s sure plenty of it.

Wherever there are headphones—and there were plenty in the LVCC—you’ll find Tyll Hertsens of Inner Fidelity.

Inside the LVCC was a crowd that made a certain bulky claustrophobe awfully uncomfortable. I should’ve stopped and asked Watson how to overcome that.

No clue what this glowing car had to do with anything. Navigating the five digit booth numbers in the Central Hall was not an easy thing, and I bounced from this thing…

…to yet another giant booth with stunning video displays….

…and yet another “smart home” display. Wish I had a buck for every time that phrase was thrown around.

This display of House of Marley products made me think I might be nearing the Hi-Res Audio Pavilion. The Marley gear was nicely designed and branded, but the turntable was decidedly toylike.

Eureka! The Hi-Res Audio Pavilion!

If it’s hi-res, you’ll find Marc Finer of the Digital Entertainment Group—here on the left, chatting with Ed Cherney from the Recording Academy’s Hi-Res Audio Committee…

…and you’ll likely also see Cookie Marenco and Patrick O’Connor from Blue Coast Records.

Escaping the crowd, outside the complex was one of the most interesting displays (to this motorhead, anyway): truck manufacturer Paccar (Kenworth, Peterbilt, DAF, etc.) showed a big rig with a fuel cell-powered drivetrain.

Sometimes a little distance aids perspective. After the show, away from the crowds and the noise…it’s all beautiful at night.

The view from atop Stratosphere.

Looking north from a balcony at the Westgate. The Red tower is Stratosphere.

Once again, I survived. Despite my doom-saying, there were signs of life for high performance audio at the Venetian, and a number of very happy exhibitors.

I escaped before the last day of the show, avoiding the pressurized petri dishes that all airlines become after the end of the show. Thus far, no toxic CES crud—just a relatively minor cold.

Back next year? We’ll see.