In Part One of this series (Issue 130), Galen Gareis of ICONOCLAST cables and Belden Inc. began an extensive exploration into a critical but not often discussed aspect of cable design: the velocity of propagation (Vp) of audio signals. In the second segment (Issue 131), he looked at practical ways to change the velocity of propagation and improve signal linearity for the benefit of better cable performance, and examined other subjects. In this final installment, Galen looks at resistance, the effects of various dielectrics, wire geometry, skin effect and other considerations, and summarizes his findings.

Also, introductory material on the subject by Galen and Gautam Raja is available in Copper Issues 48, 49 and 50.

What About Resistance in Audio Cables?

The value of resistance, R, in both impedance and in Vp (velocity of propagation) equations matters at low frequencies. We generally think of resistance as insignificant and it isn’t. In fact, as we drop in frequency, R becomes more and more significant. The same is true in Vp across low frequencies. R is important to a cable’s performance if its value is selected well. Capacitance can be increased to improve the denominator in the low-frequency Vp equation, but we also need to consider the effects of capacitance in creating amplifier problems. If a cable’s capacitance is too high, it can create serious problems with power amplifiers, including instability. This can make amps bright or harsh.

Amplifiers are measured with resistive loads. The specifications you see aren’t really true when driving a speaker cable and speakers, where there is added reactance. The real-world amplifier’s performance is worse than the best case 8-ohm load tests. We don’t want to aggravate that issue with the speaker cable if we can keep reactance mitigated and still achieve the advantages of a cable with low time-based distortion.

We can’t always rely on ignoring what we think is “passive.” After all, R is real and since you want to manage Vp across the frequency range, the value of R is critical. And what you do to the cable to raise the value of R will also impact inductance, L, and capacitance, C.

Let’s take another example and see if XLR and RCA interconnect cables exhibit the same rise in impedance with frequency.

ICONOCLAST RCA and XLR cables are designed to have the exact same impedance and phase; thus the sound quality will track one to the other. I didn’t want to make two different sounding cables, just two different physical designs.

Wow, look at the 100 Hz impedance – 2,200-ohms – and boy oh boy, does the impedance rise as frequency drops. That’s a physical reality caused by the change in Vp. Is this a problem, though? What’s happening?

Both cables have 12.5 pF/foot capacitance and 0.15 uH/foot inductance. Those are extremely low values for interconnect cable. The RCA design’s DCR (direct current resistance) loop resistance, to a first-order approximation, is the same as the coaxial cable’s 25 AWG center wire. The coaxial’s double braid has such a low resistance that it is electrically invisible. The there-and-back loop DCR pretty much “sees” just the center wire’s DCR. The low double-copper-braid DCR also mitigates ground loop noise issues. It can’t stop them altogether, because, due to the cable’s construction, this is really its ground point reference value.

The XLR uses two 25 AWG wires or four 30 AWG wires (in the case of our Series II cable). In either design, the loop DCR matches the RCA conductor equivalent. We halve the resistance by using more wires so the there-and-back DCR is like one 25 AWG wire or four 30 AWG wires. This is why the loop DCR matches that of the RCA.

The reactive basis in RCA and XLR cable is matched by duplication of the loop area and this sets the capacitance, too. This was not done by accident. The chart below models the dielectric efficiency, and the needed parameters to do so. 0.0179” wire was the best mathematical model for performance in this single wire design with the tube area (inner tube on the RCA or one of the four dielectric chambers in the XLR).

RCA DIELECTRIC EFFICIENCY

This chart shows the asymptotic nature of the dielectric efficiency curve. The design “centers” close to the peak, and does so with the best wires’ size (smaller size and higher resistance) for minimizing Vp differential.

Note that the chamber volumes, the tube inside diameter on the RCA interconnect and each of the four chambers inside the XLR, match @ 0.00755 SQR*INCH.

Audio interconnect cables terminate into a theoretical infinity load. The industry decided that infinity is 47 kohms as a standard, and higher resistance is even better. If we look at the load value presented to the cable, the load is so large that the cable becomes nearly not there electrically. Essentially, there is no current flow, and voltage signals are transferred across the end of the cable as though it was terminated into “nothing.” The very low R and C in the Vp equation are what cause the impedance rise. Since the load is extremely high, the cable’s open-short impedance isn’t an issue as the signal essentially drops across the load and not the cable.

Our Series II RCA and XLR interconnects address the issue of Vp linearity by increasing the AWG resistance to 30 AWG wire, and raising the capacitance to 17.5 pF/foot. This flattens the Vp non-linearity. We can’t go to too high a capacitance, as voltage transfer functions like to “see” low capacitance. In order to maintain phase integrity through the audio band, the signal likes to “see” low inductance, and the cable’s quad-wire design lowers inductance to 0.11 uH/foot while improving Vp linearity (smaller higher DCR wires in parallel). Like all cable designers, we have limits to how and where we move the cable’s non-linearity region.

Application of Knowledge

What does all this mean?

We need to increase capacitance and/or increase resistance to flatten Vp through the higher-frequency audio band.

Low-impedance matching between amps and speakers is hindered by rising capacitive reactance as frequency drops.

Improving Vp linearity only by using higher capacitance increases impedance at low frequencies by changing the capacitive reactance.

Capacitance has to be mitigated to improve low-frequency impedance. We should use wire resistance rather than design capacitance in managing higher-frequency Vp linearity if possible.

There is a limit we can reach before other variables are compromised, like inductance, total loop DCR, dielectric efficiency and DCR voltage-divider properties. Each cable parameter has to be carefully solved separately and then overlaid onto the Vp differential results to see how the overall cable works. How we reach the best balance of R, L and C can result in some unique analog cable designs when we really try to reach best-in-class analog performance.

Regarding wire geometry; most people don’t really understand everything about how the use of many and/or small wires in a cable really works. However, using multiple wires has several advantages.

Smaller wire cross-sections improve conductor current efficiency and smooth out the velocity of propagation (Vp) curves. The current-through-wire cross-section is closer and closer to being the same across frequencies, as wires get smaller and smaller. If a wire could be made that was one atom wide and worked, we would have no issues at all with skin depth.

Small wires improve conductor efficiency at the higher frequencies, where the skin (wire self-inductance) effect pushes the current towards the wire surface. At low frequencies the proximity effect pushes (current in the opposite direction) or pulls (current in the same direction) current to one side of the wire. Both aspects hinder full utilization of a wire’s area.

http://www.electricaltech4u.com/what-is-proximity-effect/

Solving Vp differential in the different wires in a cable as frequency rises isn’t straightforward. The wire’s self-inductance makes the center of a larger and larger wire act more and more like a high-impedance path to current flow than the center of a smaller wire. And, as current flow goes up, proximity effect alters how current wants to flow in the wire’s center. Both change the effective resistance at that specific frequency. For an easy approximation we use the DC resistance value, and this is clearly not “correct.” But, the approximation errors to improve Vp linearity, the true Rs (swept resistance) value goes up as frequency goes up, and that’s what the cable needs.

The measurement of one unit of skin depth, per the definition of skin depth convention, is when the current in the subsurface of a wire is 37 percent of what it is on the wire surface at specific frequencies. However, if a wire is small enough, it may never see current drop to 37 percent. Conversely, a really large wire may see near zero current in the wire’s center at specific frequencies, with the 37 percent value happening somewhere between the wire center and the wire surface.

We can improve wire efficiency through the audio band by either making the wire smaller, or removing the center of the wire, where the copper isn’t used as efficiently anyway. In fact, at RF frequencies, where the skin effect is in full force, we replace the copper with cheaper materials like steel, CCS (Copper Covered Steel), SPCCS (Silver Plate Copper Covered Steel) or CCA (Copper Covered Aluminum). In other cables, we plate the copper with other materials to replace the copper’s properties with something better.

Some audio cable designs in fact use hollow wire, but these are larger-diameter structures with the lower DCR working against flattening the Vp curve. Small multiple wires are needed in analog cables for the best performance; ICONOCLAST uses four in the RCA interconnects, 16 in the XLR interconnects and 24 for each positive and negative side (48 total) for our speaker cable. The total number of strands used depends on the voltage divider rule referenced previously; the current in each polarity drops voltage across that “section.” We don’t want the voltage across the cable, we want it to be across the load. If the cable is of low-enough resistance, or the current in a wire is low enough, the voltage drop is mitigated.

But in all designs, more so on speaker cables, we can “trick” the voltage drop issue by dividing up the current between all the small wires. Current will split equally into each identical parallel-resistance wire, and thus have a lower individual current value. Voltage is current times resistance; E= I*R, so the voltage drop on each small wire is pretty low as we drop the current, I, even if we increase the resistance, R.

Most interconnect cables work with one small wire per conductor, as they use 25 AWG or so signal wires. They carry little to no current, so a low DCR wire isn’t, to a first approximation, necessary. However, the math says Vp linearity can improve if we try.

The use of numerous insulated wires increases capacitance, which seems initially good for flattening the Vp curve, but that changes L in the opposite direction and significantly too if you’re not careful, which is bad for phase response. The pesky third R, L or C inter-related variable is always there no matter which other two you choose to address. To manage inductance as capacitance rises with the use of more wires in a cable’s construction, we employ star-quad phase-cancellation technology to limit inductance in both our speaker and Series II interconnect cables.

The single polarity of a Series II XLR interconnect (see the diagram below) uses four bare 30 AWG wires. The electromagnetic (EM) fields cancel as the current in all four wires is in the same direction. Opposing arrows show the EM field cancellation. Both the Series I and TII XLR interconnects use an overall star-quad configuration to further reduce the EM field. The Series II has the advantage of using this technology twice, reducing inductance from 0.015uH/foot nominal of the Series one to 0.11 uH/foot in the Series II cable.

In the TPC, SPTPC and OFE speaker cable, a clever use of bonded pairs in a special weave forces a periodic star-quad arrangement like the XLR, or near so, to form inside each positive and negative side of the cable. Currents are all in the same direction, like the XLR, resulting in EM field cancellation. This reduces the inductance from 0.126 uH/foot a single bonded pair by itself, to just 0.08 uH/foot in a finished speaker cable.

INSIDE THE QUAD XLR CONDUCTOR

INSIDE THE SPEAKER CABLE POLARITY

Since we’re working in the audio frequency range we utilize the entire cross section of the wire, and we want it to be efficient at all frequencies. This is called diffusion coupling. This means the use of solid wire is best. We can’t remove the wire center as audio frequencies use this area. If we used a thin copper tube wire, we’d have far larger cable and costlier designs with no advantages.

Unlike RF, where we can whittle away the center area, we don’t want to do that at audio. We need to use one or more wires depending on the design to reach the proper DCR and Vp differential without excessive capacitance and inductance, and keep current across the entire wire as uniform as we can.

More About Speaker Cable Design

Our ICONOCLAST speaker cable utilizes many small 24 AWG wires that have a relatively low 45 pF/foot capacitance. I chose to use a higher capacitance to lower the Vp differential across the frequency range, with 24 higher-DCR 24 AWG wires per polarity (shown). Both of these attributes improve the Vp differential as we saw in the Vp analysis math.

The design of the speaker cable allows us to precisely control the capacitance. Using such a large number of small wires meets the “voltage divider” bulk DCR properties of the cable and the use of our field-cancellation technology lowers the inductance to 0.08 uH/foot. Teflon insulation is used to allow tighter wire spacing and, to hold capacitance down and to decrease loop area. The cross-weave design cancels magnetic fields to further drop inductance.

Interconnect Design Details

Earlier the aspects of how to achieve proper dielectric efficiency was shown for the RCA and XLR interconnect.

Our Generation One XLR and RCA cables use a small 25 AWG wire and have a low 12.5 pF/foot capacitance. The small center wire improves the Vp differential, while the air (hollow air core) dielectric allows tighter spacing at a given capacitance, which yields a lower inductance of 0.15 uH/foot, facilitated through a small loop area.

Our Generation Two XLR and RCA cables use a four wire 30 AWG “conductor” to increase the separate wire path DCR to lower Vp differential even more. The capacitance DOES go up however, to 17.5 pF/foot. The smaller 30 AWG wire with higher a DCR combined with increased capacitance lowers the Vp differentials even further. The changes, capacitance increase and smaller wire (higher DCR) leverage the Vp differential over “bandwidth” from lower capacitance. Listening tests show this to be a better-sounding cable.

Our Generation Two XLR and RCA cables use a four wire 30 AWG “conductor” to increase the separate wire path DCR to lower Vp differential even more. The capacitance DOES go up however, to 17.5 pF/foot. The smaller 30 AWG wire with higher a DCR combined with increased capacitance lowers the Vp differentials even further. The changes, capacitance increase and smaller wire (higher DCR) leverage the Vp differential over “bandwidth” from lower capacitance. Listening tests show this to be a better-sounding cable.

SERIES ONE (LEFT), SERIES TWO (RIGHT)

A Series II dual-star-quad design (see right diagram) lowers inductance to 0.11uH/foot to keep phase through the audio band lower than the Generation One design. These design attributes allow a technically better analog cable to be made than our Series One (left diagram).

Our RCA and XLR interconnects have the same loop DCR in each design. How is this done? The RCAs loop DCR is essentially the center signal wire, as the braid has almost zero DCR. This is why the center wire DCR is so, so important: it’s the “R” in the Vp differential equation.

The star-quad 4×1 XLR interconnect (above left) features a full loop that uses two wires in parallel. This results in a DCR that is the same as one wire’s measured value. We cut the DCR in half in each direction, so a full loop is now the same as one wire’s.

The 4×4 XLR (above right) uses four separate wires per leg, of higher DCR value, which lowers the Vp differential. Since we use four wires in parallel, the loop DCR is lower than the 4×1 XLR even though we increased the apparent signal wire DCR with four insulated current paths. The XLR wire size is critical to performance in the audio band. The loop DCR is equivalent to using four 30 AWG conductors in parallel.

Summary:

The ideal cable is always a balance of competing electrical properties. The electrical property of resistance isn’t as benign as we would like to think, and resistance has to be factored into a well-performing cable configuration. This can result in some complex but effective designs.

Inductance and capacitance are problematic, as they have a push-pull relationship. One goes up when the other goes down. We need to configure designs that are low in L and C from the start. In my studies, allowing capacitance to rise somewhat is necessary to enable the desired result of flattening the velocity propagation curve, but can’t allow capacitance to reach unacceptable values that would affect an amplifier.

All the mentioned variables are real. The net results of the effects of R, L and C in a cable are important. The ideal cable can’t really be made, though, because cables are a reactive component that interact with the other components in an audio system.

If we consider the tertiary, or unmeasurable aspects of a cable, such as wire metallurgy material contributions and polarization speeds of dielectrics and the like, they have to rest on a solid foundation of the primary and secondary effects that we can control. ICONOCLAST is made considering both mathematical calculations and real-world measurements, in order to make the best-possible cables that current-manufacturing processes can meet.

That cables sound different isn’t a mystery to me. If the variables that relate to time-based effects are improved, the sound of the cable can be improved. As we like to say, sound designs create sound performances.

Return to Table of Contents

Our 1961 Moore jig borer and 5,000 lb.-capacity forklift truck, ready for action.

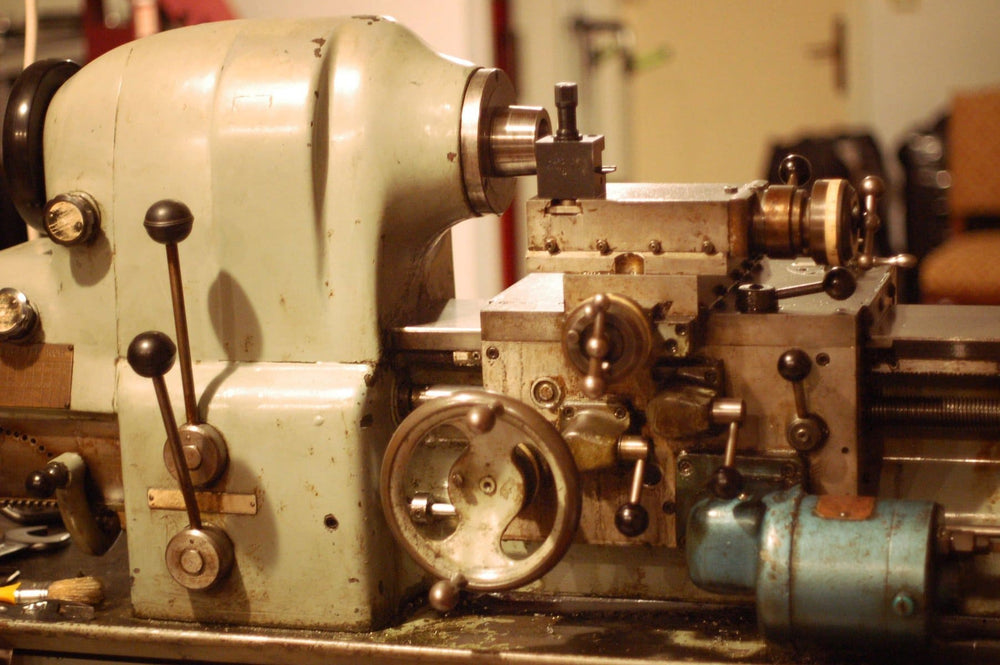

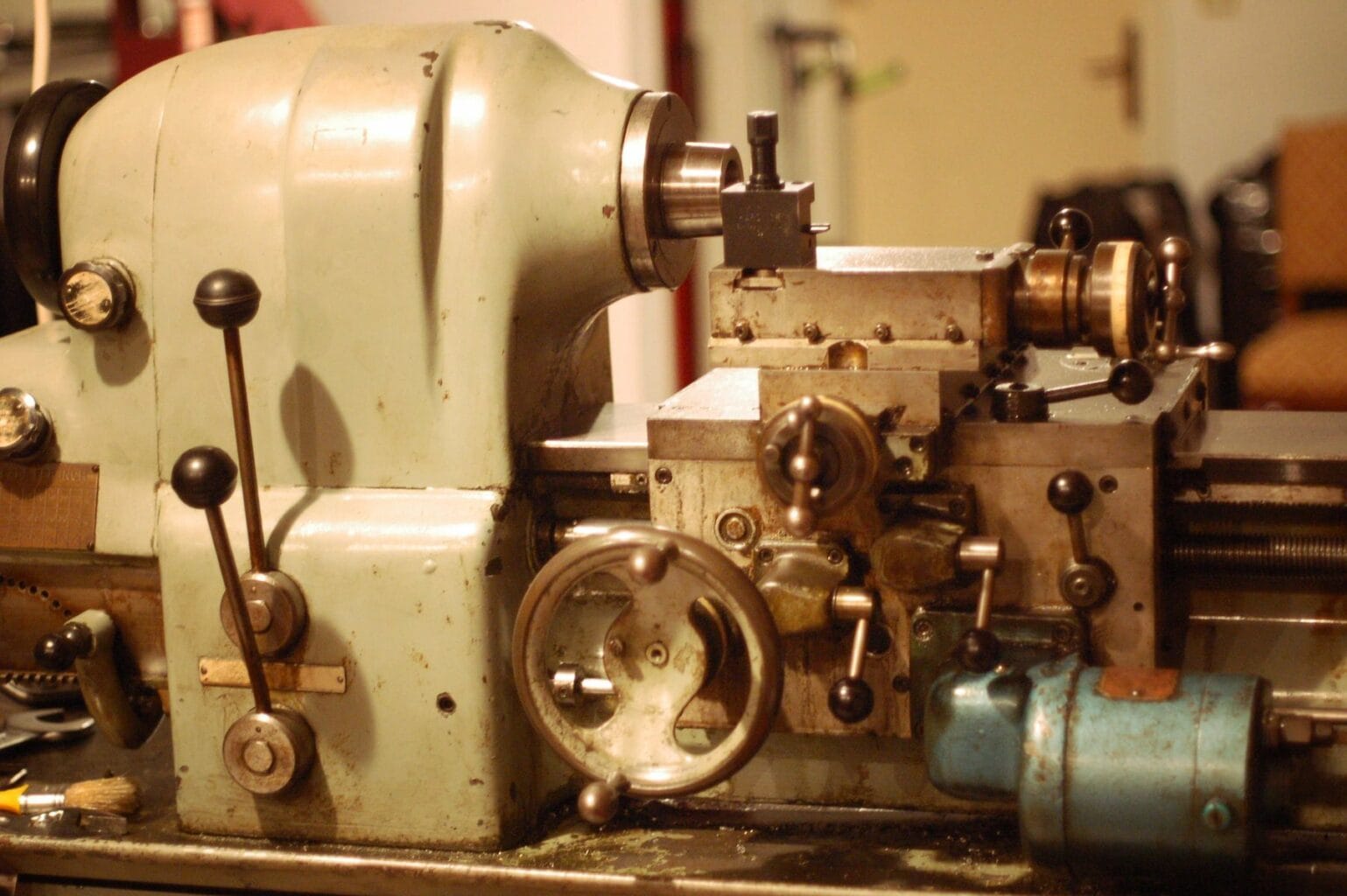

Our 1961 Moore jig borer and 5,000 lb.-capacity forklift truck, ready for action. The 1954 Hardinge HLV super-precision lathe in the new building.

The 1954 Hardinge HLV super-precision lathe in the new building. The spindle housing of the Moore jig borer.

The spindle housing of the Moore jig borer. A V-8 powered Cadillac Eldorado and a few lawnmower-engine Yugo 45s (along with an older Zastava 750) parked outside a typical example of a socialist apartment block in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, where everyone could have the same car and identical apartments, as observed on one of many interesting business trips, during which the author built character…

A V-8 powered Cadillac Eldorado and a few lawnmower-engine Yugo 45s (along with an older Zastava 750) parked outside a typical example of a socialist apartment block in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, where everyone could have the same car and identical apartments, as observed on one of many interesting business trips, during which the author built character… The Moore jig borer, the forklift and a huge crane approaching...

The Moore jig borer, the forklift and a huge crane approaching... The crane and forklift working together to tilt the Moore jig borer.

The crane and forklift working together to tilt the Moore jig borer. The Moore jig borer suspended on its back, guided through the arched entrance of the machine shop.

The Moore jig borer suspended on its back, guided through the arched entrance of the machine shop. Possibly the most inappropriate entrance in the world for huge industrial machinery. We live in hope that once the editor of Veranda decides to extend the scope of the publication to machine shops, ours will be the first feature!

Possibly the most inappropriate entrance in the world for huge industrial machinery. We live in hope that once the editor of Veranda decides to extend the scope of the publication to machine shops, ours will be the first feature! The Moore jig borer on its back, strapped onto a special trolley on which it was pushed by hand inside the building.

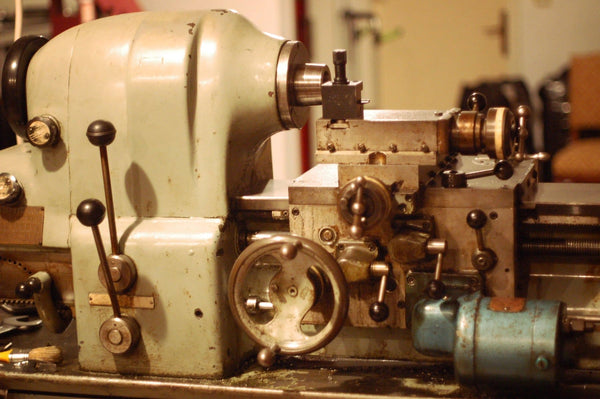

The Moore jig borer on its back, strapped onto a special trolley on which it was pushed by hand inside the building. The apron of the Hardinge HLV lathe, with longitudinal feed wheel, cross-feed ball-crank handle, power feed motor, feed clutch levers, half-nut engine lever, carriage lock lever and sight glass for maintaining the oil level.

The apron of the Hardinge HLV lathe, with longitudinal feed wheel, cross-feed ball-crank handle, power feed motor, feed clutch levers, half-nut engine lever, carriage lock lever and sight glass for maintaining the oil level. A collection of small parts for disk recording lathes, machined by the author.

A collection of small parts for disk recording lathes, machined by the author. Our Moore Ultra-Precision Rotary Table. It is about as heavy as me!

Our Moore Ultra-Precision Rotary Table. It is about as heavy as me! The Monarch 10EE precision lathe, developed in part by Western Electric.

The Monarch 10EE precision lathe, developed in part by Western Electric. One of the generously-dimensioned dials of the Moore jig borer, allowing the operator to directly read down to 0.0001", with a comfortable handwheel and the silky-smooth action of the Nitralloy leadscrew.

One of the generously-dimensioned dials of the Moore jig borer, allowing the operator to directly read down to 0.0001", with a comfortable handwheel and the silky-smooth action of the Nitralloy leadscrew. The custom pedestal on which the jig borer is mounted to operate as a thermal island.

The custom pedestal on which the jig borer is mounted to operate as a thermal island. The Weston thermometer on the spindle housing of the Moore jig borer allows the operator to take thermal expansion effects into account, for maximum accuracy.

The Weston thermometer on the spindle housing of the Moore jig borer allows the operator to take thermal expansion effects into account, for maximum accuracy. A toolmaker’s microscope on our 1930s Lorch optical lathe.

A toolmaker’s microscope on our 1930s Lorch optical lathe. The electrical control panel for the Moore jig borer. The spindle speed is varied by means of a mechanical expanding and contracting pulley system, packaged as the General Electric Polydyne unit.

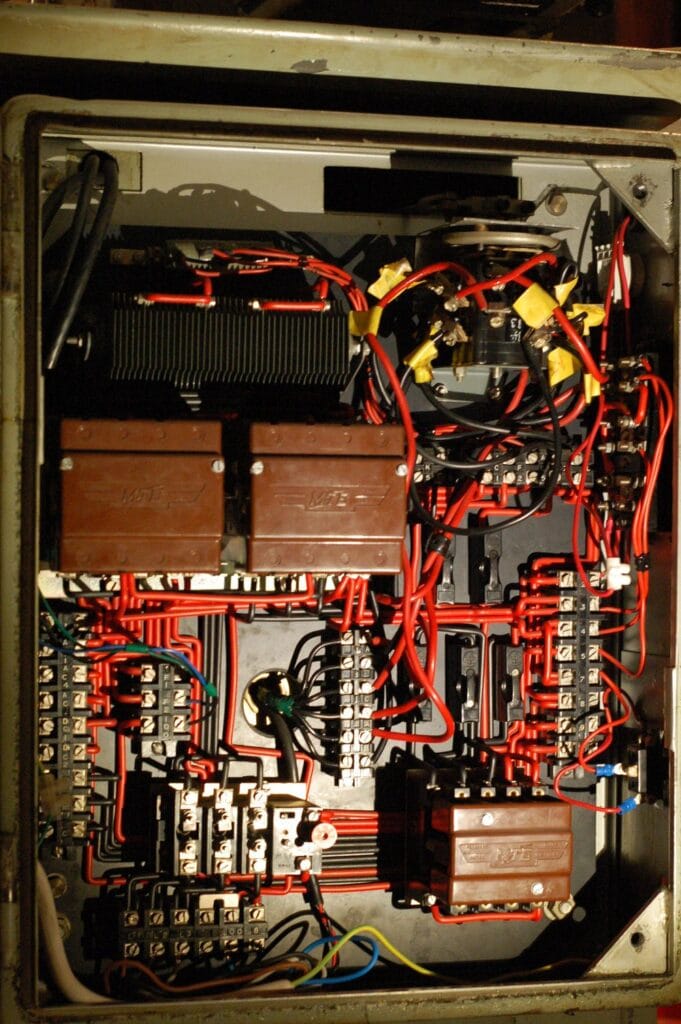

The electrical control panel for the Moore jig borer. The spindle speed is varied by means of a mechanical expanding and contracting pulley system, packaged as the General Electric Polydyne unit. The electrical control panel for the Hardinge HLV lathe, which also uses expanding and contracting pulleys for spindle speed control and an autotransformer for feed speed control.

The electrical control panel for the Hardinge HLV lathe, which also uses expanding and contracting pulleys for spindle speed control and an autotransformer for feed speed control.

This chart shows the asymptotic nature of the dielectric efficiency curve. The design “centers” close to the peak, and does so with the best wires’ size (smaller size and higher resistance) for minimizing Vp differential.

This chart shows the asymptotic nature of the dielectric efficiency curve. The design “centers” close to the peak, and does so with the best wires’ size (smaller size and higher resistance) for minimizing Vp differential.

Our Generation Two XLR and RCA cables use a four wire 30 AWG “conductor” to increase the separate wire path DCR to lower Vp differential even more. The capacitance DOES go up however, to 17.5 pF/foot. The smaller 30 AWG wire with higher a DCR combined with increased capacitance lowers the Vp differentials even further. The changes, capacitance increase and smaller wire (higher DCR) leverage the Vp differential over “bandwidth” from lower capacitance. Listening tests show this to be a better-sounding cable.

Our Generation Two XLR and RCA cables use a four wire 30 AWG “conductor” to increase the separate wire path DCR to lower Vp differential even more. The capacitance DOES go up however, to 17.5 pF/foot. The smaller 30 AWG wire with higher a DCR combined with increased capacitance lowers the Vp differentials even further. The changes, capacitance increase and smaller wire (higher DCR) leverage the Vp differential over “bandwidth” from lower capacitance. Listening tests show this to be a better-sounding cable.

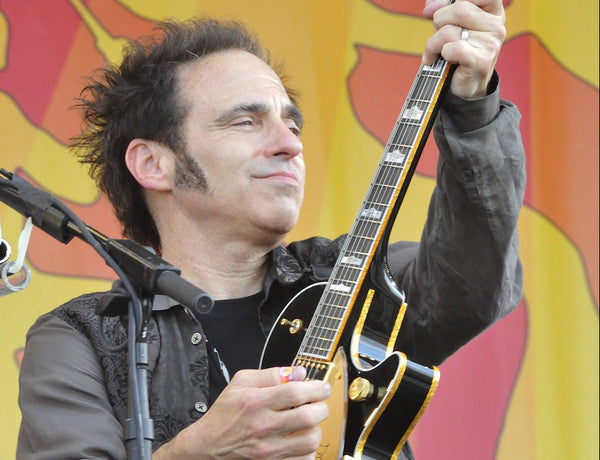

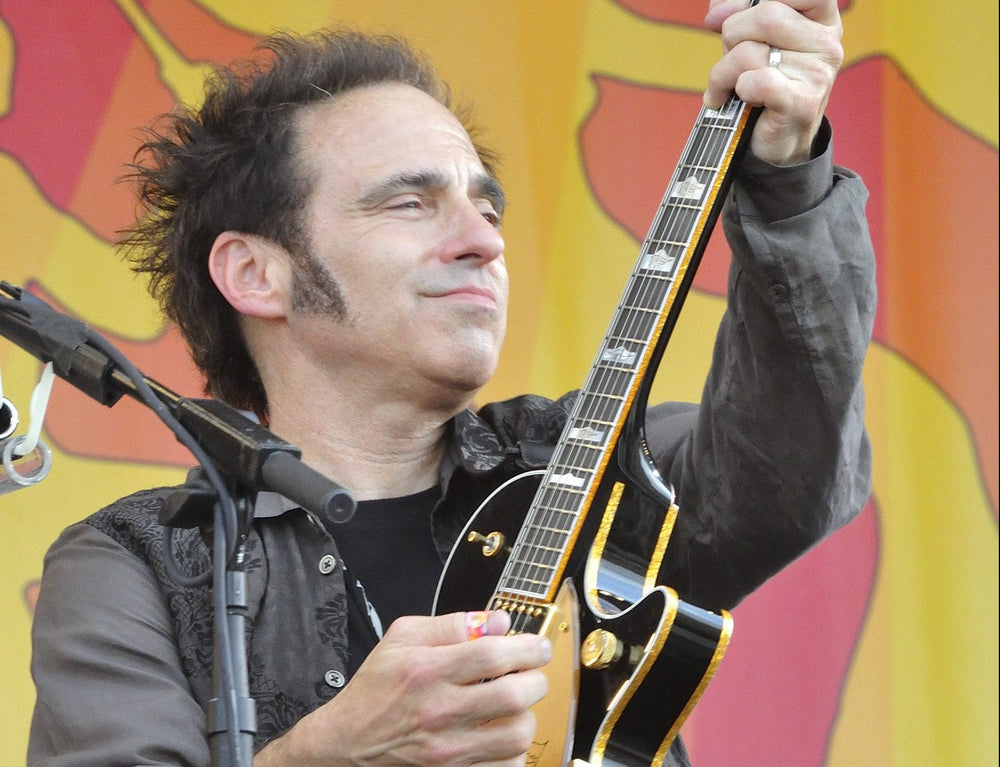

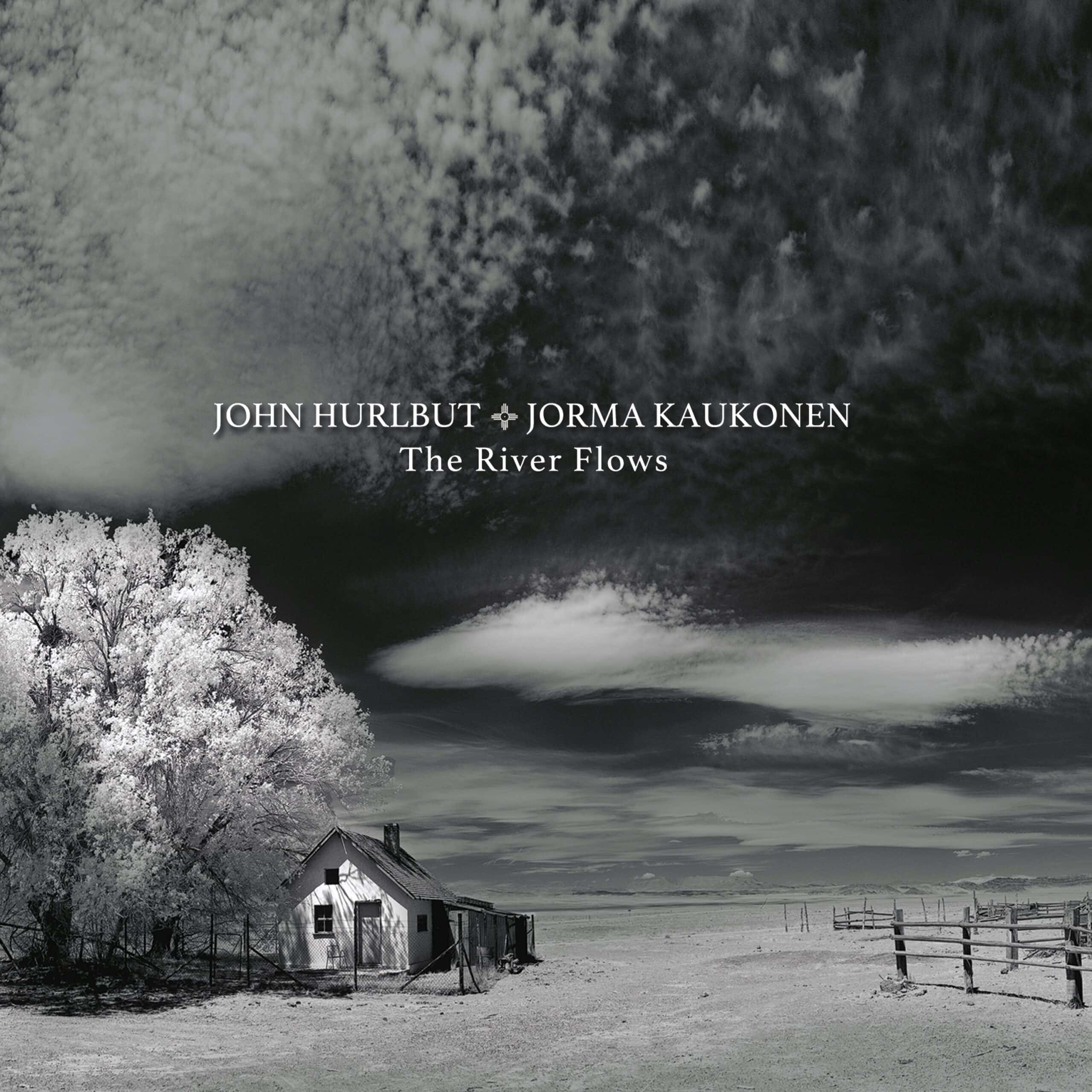

Jorma Kaukonen and John Hurlbut. Photo credit: Scotty Hall.

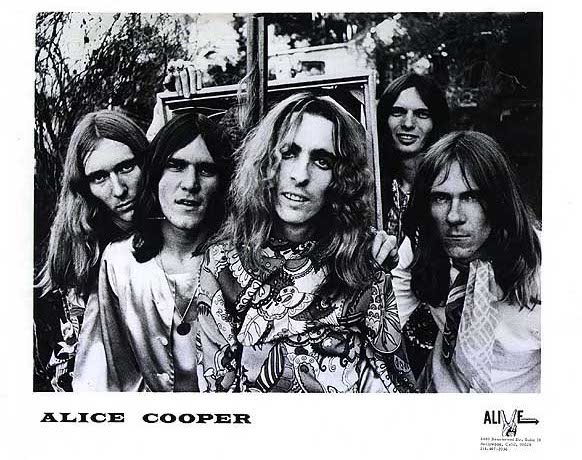

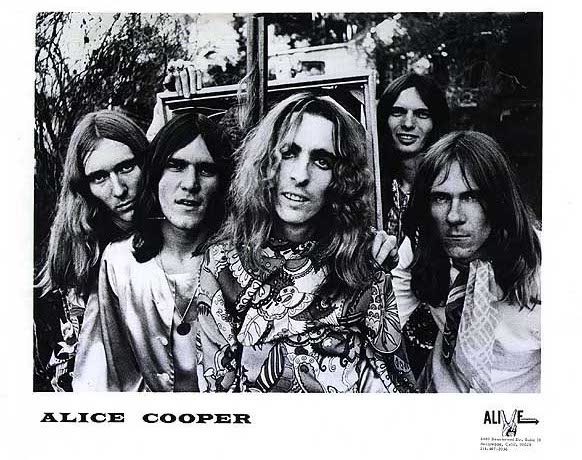

Jorma Kaukonen and John Hurlbut. Photo credit: Scotty Hall. Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen, 2009. Courtesy of

Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen, 2009. Courtesy of

An AAGS grading certificate.

An AAGS grading certificate.