Nicky Hopkins is hardly an unknown entity in the world of rock music. A stellar piano/keyboard player, even the most modest rock fan is likely familiar with his work. Think about the opening bars to the Stones’ “She’s a Rainbow” or “Monkey Man.” Or how about Hopkins’ beautiful piano solo during the bridge in “Angie?” Many, many years after collaborating on John Lennon’s song “Jealous Guy,” Yoko Ono commented, “Nicky Hopkins’ playing is so melodic and beautiful, that it still makes everyone cry, even now.”

Hopkins’ style indeed was always considered melodic and never flashy, and with contributions to so many iconic albums and songs, he unquestionably is an integral part of the history of rock music. What’s probably unbeknownst to many Copper readers, however, is how deeply entrenched Hopkins work is across such a wide range of 1960s and 1970s recordings, a prolific period when Hopkins was the most sought-after session keyboardist in the business, and whom many (still) consider the world’s best.

How many musicians can say they made invaluable contributions to classic tracks from the Beatles, Stones, the Who, Kinks and Jeff Beck? Absolutely none, other than Nicky Hopkins. How about contributions to solo albums for all four Beatles? Then throw in Ella Fitzgerald, Cat Stevens, Joe Cocker, David Bowie, Art Garfunkel and Joe Walsh, and you can see how diverse Hopkins’ musical contributions were, and not so easily stereotyped.

Of course, many music fans are familiar with legendary “studio bands,” or groups of session musicians that recorded as a team for many well-known artists during the 1960s and beyond. These studio bands included the Wrecking Crew, the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section and Booker T & the M.G.’s, the house band for Stax Records. But these were all group collaborations, as invaluable as they may be.

Here’s just a small sample of albums Hopkins contributed to over the years:

Rolling Stones: Their Satanic Majesties Request, Beggars Banquet, Let it Bleed, Sticky Fingers, Exile on Main Street

Beatles: The Beatles (The “White Album”); John Lennon – Imagine, Walls and Bridges; Paul McCartney – Flowers in the Dirt; George Harrison – Living in the Material World, Dark Horse; Ringo Starr – Ringo, Goodnight Vienna

The Who: My Generation, Who’s Next, The Who by Numbers

Kinks: The Kink Kontroversy, Face to Face, Something Else by the Kinks, The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society

Jeff Beck Group: Truth, Beck-Ola

Jefferson Airplane: Volunteers

Quicksilver Messenger Service: Shady Grove, Just For Love, What About Me

Steve Miller Band: Brave New World, Your Saving Grace

Carly Simon: No Secrets

You can also add-in Hopkins’ highly melodic piano on Joe Cocker’s soulful rendition of “You Are So Beautiful,” a song written by another great keyboardist and child prodigy, the late Billy Preston. For all intents and purposes, this beautiful arrangement is just Cocker’s vocals with Hopkins’ piano underneath.

Nicky Hopkins was born outside of London in 1944 in the middle of an air raid drill, a stark contrast to the reserved personality he would be known for. Built wisp-thin, Hopkins had a lifelong struggle with poor health, including battling Crohn’s disease and having many surgeries. Hopkins was bedridden for an unconscionable nineteen months during his late teens after surgery to remove a kidney and gall bladder. A love for the bottle unfortunately added to his poor health. It probably wasn’t particularly helpful that during his formative years, Hopkins’ family lived close to a Guinness brewery, where his father worked as an accountant.

Hopkins exhibited prodigy-like talent at a very early age. After winning a local piano competition, he received a scholarship to London’s prestigious Royal Academy of Music. He studied there from the ages of 12 to 16 and was a contemporary of another scholarship recipient by the name of Reginald Dwight, a.k.a. Elton John.

His classical studies were interrupted and ended prematurely when he began performing with prominent local bands (i.e., Screaming Lord Sutch) that ultimately lead to an early ’60s residency with British R&B legend Cyril Davies at London’s famed Marquee Club. From that exposure, demand for Hopkins’ session work began to blossom.

Hopkins’ formal training would later serve to be an asset in the studio, particularly to legendary producers George Martin (the Beatles), Andrew Loog Oldham (the Rolling Stones), Shel Talmy (the Who, the Kinks) and Simon Napier-Bell (Jeff Beck). Said Talmy of Hopkins at the time, “Nicky Hopkins is the most promising pianist/arranger on the music scene today; that goes for both sides of the Atlantic!”

If a producer thought a change in key was needed for a song, it was often relegated to Hopkins to develop new chord charts for other musicians who were only self-taught. Composer/arranger and ex-Manfred Mann guitarist Mick Vickers once said of Hopkins, “there are people who read music and don’t make things up, and people who make things up and don’t read music, so when you put them together it’s a powerful thing.”

When asked to describe his playing style, Hopkins offered, “I can hear things in my playing that sound a bit like Albert Ammons [the boogie woogie, jazz-style pianist popular in the late 1930s] or in a rare instance maybe, like Rachmaninoff. I don’t know if I sound like A, B, C, or D. I’ve assimilated so many peoples’ styles of playing over the years, plus, I guess, my own too.”

Reminiscing on the session and mix for the Rolling Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” Hopkins had this to say: “the piano is way too low. I was playing the piano with my left hand and the organ with my right at the same time on that track. I always disliked guitar players’ ears, which is what most engineers have.” He then mockingly added with a laugh, “the piano is so difficult to mix, so we’ll just turn it down.”

There were occasional periods when Hopkins was a permanent member of a group, such as The Jeff Beck Group, Quicksilver Messenger Service and the short-lived but excellent band Sweet Thursday (which also included Alun Davies, Jon Mark and others). He did manage to play with the Jefferson Airplane at Woodstock in 1969, in addition to the Stones’ infamous and debauchery-laden 1972 North American tour. However, road opportunities for Hopkins were fleeting, as either the bands he was in would break up or his ailing health would get in the way.

As a session musician, Hopkins frequently found himself working side-by-side with Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, both also well-known and highly regarded session players at the time. Given their friendship and mutual respect, it is said that Hopkins actually turned down an opportunity to join an early version of Led Zeppelin.

As a “hired gun,” Hopkins only received album liner note credits, and sometimes even then he was shortchanged. Session players frequently make valuable contributions to a song, with a riff here or a chord change there, without receiving the credit or recognition they deserve. Hopkins never received royalty payments, outside of the generosity of Quicksilver Messenger Service and their management company for select recordings.

Session work depends a lot upon a player’s chemistry with the primary artist, his or her style of play and what kind of contributions an artist is seeking, amongst other things. Sometimes the artist and producer know exactly what they’re looking for, sometimes they don’t. Ideally, they’re open to input, especially if a session musician has chops and a strong reputation to go with it.

The Kinks’ Ray Davies, who Hopkins didn’t have a particularly good relationship with, reflected on the band’s Face to Face sessions by noting, “Nicky Hopkins looked so thin and pale, it was as if he had just been whisked out of intensive care and dragged in on a stretcher so he could play piano on our track.” Wow, way to dole out the compliments, Ray!

In 1966 The Revolutionary Piano of Nicky Hopkins was released, an instrumental album designed to showcase Hopkins as a solo artist. Producer Shel Talmy thought it was a good idea to turn Hopkins into a frontman. The LP consisted of a strange and eclectic mix of songs, including a somewhat jazzy interpretation of the Stones’ “Satisfaction.” The LP did not sell particularly well, in part due to lack of record label support.

In 1973 Hopkins attempted another solo project with the LP The Tin Man Was A Dreamer, a Columbia records release that I still own. In this effort, Hopkins flexes his pipes on lead vocals, accompanied by a slew of well-known musicians and friends, including George Harrison, Mick Taylor, Klaus Voorman and Bobby Keys. Although Tin Man received some decent reviews, I can only say that perhaps it’s an acquired taste. A third solo album, No More Changes, was released in 1975.

In sum, one can be a great musician, which Hopkins unquestionably was, but being a great songwriter requires an entirely different skill set.

In 1994, after complications from intestinal surgery, Hopkins sadly succumbed to his poor health at the young age of 50. When news of Hopkins’ death reached old friend Ian McLagan of Small Faces fame, he and his wife decided to go for a drink to celebrate his life. When they entered a bar for a round of beers, without any action or provocation on their part, the Stones’ “Street Fighting Man” came on the jukebox, followed by an unbroken succession of songs Nicky Hopkins played on. When McLagan asked the barkeep if she knew who Hopkins was, assuming there was a connection, she said she’d never heard of him and that if nobody put money in the jukebox; it played its own random selections. It was pure karma, and they were thrilled!

In 2019, on what would have been Hopkins’ 75th birthday, London’s Royal Academy of Music posthumously bestowed a scholarship in his name and honor.

Nicky Hopkins is an unsung hero, a keyboardist of extraordinary talent whose contributions to music will live on today, tomorrow and the next day. It’s a legacy that’s quite well deserved.

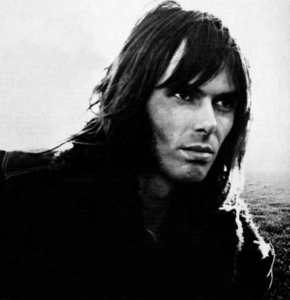

Header image of Quicksilver Messenger Service in 1970 (Hopkins is second from right) courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/public domain.

0 comments