[Bert van der Wolf is a distinguished Netherlands-based engineer/producer with over thirty years’ experience in developing and advancing high-resolution, multichannel classical recording. Recently he agreed to share his thoughts with us on a variety of topics.]

You have an extraordinarily wide range of experience within the industry. How did you get started on this path?

As a child I discovered I was quite good at playing musical instruments, first piano, later guitar, both classical and pop/jazz. I wanted to study at a conservatory after high school. However, my father encouraged me to consider something more reliable than music, because he felt the odds were against making a living in it. So I started out studying electrical engineering. After three years I got fed up with the culture at that school. I tried to apply at Polygram for an internship, but around then they started accepting only students from the Koninklijk Conservatorium’s recording department. I immediately decided to skip to the conservatory, but first I had to perform military service for a year. The rest is history! At the conservatory, I felt like a fish in the water and basically became a professional producer/engineer in two years, half the usual time needed for the course. I got an internship at Channel Classics and “fell with my nose in the butter,” as they say, because they were just starting the label. I recorded their first 100-plus productions, not to mention countless third-party jobs for other international labels.

What are your earliest memories of hearing good or bad records, of modifying equipment, developing musical values?

I remember listening to my first audio equipment, under my bed, with two different tube radio receivers; I had constructed my own proprietary stereo cartridge from what had been a mono Philips record player. It was magical, playing the records my parents got for free at Readers Digest, just as thrilling as today, when I enjoy good recordings and playback with high-resolution multi-channel immersive formats. The feeling was the same.

And from there?

At the conservatory I was immediately struck by the joy that radiated from the lessons of my most important teacher, Adriaan Verstijnen. His passion was contagious. Every so often I was permitted to follow him around and join at projects: he was working for Harlekijn Holland and Erato, recording Ton Koopman and The Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra and artists like Reinbert de Leeuw. Later, when I arrived at Channel Classics, I got a true baptism by fire: we did over 40 projects in the first year and a half. Channel always put quality first on its agenda, so I had to perform from Day 1 at the highest level. Luckily I stayed and did well, and many musicians crossed my path.

Photos, here and above, by Brendon Heinst.

Your video from dCS (click here) reminds us of the early days of digital and how it “grew up.” What’s your 21st-century perspective?

We now have a much better knowledge of digital, how it differs from analog and how it became mature to a level that exceeds the best analog. Furthermore, the development of digital mixing tools, the enormous DSP power of edit engines and various plug-ins for reverb, delay, and more have multiplied our options for creativity in the editing and mastering room. That adds a lot to the magic and makes it more likely to communicate exactly what musicians intend to transmit onstage.

What problems remain?

The biggest problem is that digital sound, offering ultra-high resolution, often shoots past the reality of life. An ultra-high-definition TV can show a picture that does not exist in real life. You can zoom in on a fly on the wall at 60 yards and see its eyeballs if you want. In audio it sometimes feels as if transparency and dynamics have been overexposed—exaggerated, really—within the mix. High End now implies a move toward unrealistic transparency and projection from all angles of the soundstage, encouraged by equipment that enables this. But real life has logical blurs around the focal point—a point that should, in contrast, be very high-res!

Perhaps that’s how our brains typically handle live music. Somehow we choose a focal point, and everything else goes into soft focus. Does ultra-resolution work against this?

It’s not necessarily ultra-resolution that’s the problem, it is how engineers react to the new possibilities it offers. In the past, when the best technology captured less information, engineers tended to over-gather data, placing equal emphasis (or worse, over-emphasis) on all aspects of the potential mix. Then, to compensate for the lack of visual and other sensory information (the data our sight, skin, and scent collect at live performances), they created layers—depth of field—via supporting microphones, EQ, and dynamic alterations. They could offer focal points everywhere simultaneously, often incoherent in imaging and perspective.

Remember when HDTV came out? By capturing more information, the new visual transparency revealed too much of the actors’ make-up. This changed the “grime departments” at television shows forever, and vastly complicated the tasks of set decoration, lighting, and more. With ultra-resolution audio, engineers now have to come up with more subtle accents, more sophisticated mixes. That has not happened across the board. Timbres, transients, and imaging are still being overproduced, as if high-res did not exist; the make-up is showing. Analog—and DSD, in a way—comes with a nice layer of “lingerie,” a term I use for differences between real life and the “ultimate/naked” truth of high-resolution audio.

Sounds like you’re saying “a veil should not be lifted.”

Going back to cruder formats like analog tape or vinyl is certainly not the solution. I am experimenting with unique microphone setups to create a holographic image of the event with interactive transparency: finding elements in the mix that invite the listener’s engagement. I do not want to present everything on a platter. Many mixes are like McDonalds, where you get exactly what you expected. It’s consistent and in that sense “professional,” but ultimately it lacks mystery. With haute cuisine, a diner expects to seek out subtly blended ingredients, discerning their presence within the meal’s gestalt. When you listen to a good holographic recording of an orchestra, the total soundscape should grip you without anything seeming isolated or exaggerated. If a mix focuses on bits and pieces—all the individual sounds, all the moments, with pin-point accuracy—you get recognizable high-res, but not music.

Photo by Aart van der Wal

When you plan a recording session, what are your priorities?

Most important is to create an environment in which musicians can reach their optimal potential. This will be different for every artist, but in general I strive to make the experience inspirational and engaging. My contribution is only a tool; it must never become an obstacle. I am most happy if musicians start talking music immediately after hearing the first take. This means the sound is not blocking their process; it’s just another instrument we must play.

In an engineering/producing relationship with an artist, who chooses whom? What is the basis for a good working partnership?

Many artists know how to find me, and they ask labels to hire me, or they hire me themselves. Challenge also encourages musicians to work with me if they feel the project will benefit from my style. The secret to creating a good partnership is to find the artist’s ultimate strength and put the emphasis on that very aspect!

How do your methods differ from what other engineers do?

I wouldn’t know; I am never there! I do think we all need similar assortments of temperament and skill. This profession is a killer. Some people make it, some leave; there are always others ready to take over your job. I am still here after thirty years—twenty years as an independent!—so it’s clear some musicians appreciate my work.

Has your setup changed in the last ten years?

Not much. I began working in DXD (352kHz/24bit) in 2005 and developed my proprietary (HQMM) microphone matrix system around then too. Because dCS unfortunately left the pro community, I have moved toward Merging Technologies for AD/DA hardware. I still work occasionally with dCS on consumer products, but their systems are no longer compatible with current standards and demands in pro audio. The most striking development for the industry overall has been audio-over-IP, a true blessing for us, incredibly flexible, high-quality digital I/O that cuts out a lot of destructive digital processes we once had to deal with.

Recording Bruckner with Jaap van Zweden. Photo by Aart van der Wal

You created Turtle Records two decades ago. How?

It was a chance meeting with Harry van Dalen at Rhapsody Sound in Hilversum, Holland. I was distributing dCS converters on the European mainland and he wanted to do a 96/24 recording with a Nagra-D and a dCS 904. I went to his place and found a stunning shop with playback tools that I did not know of. High End!! I was mesmerized, and Harry had many of my recordings, which I suddenly heard with “new glasses on.” Our ideas about sound and the business were strikingly similar, mine from the source—the recording world—his from the playback side in consumer audio, so the very same evening we decided to start something together. I would supply the infrastructure for recording, he the network in High End and his knowledge of true high-end equipment. And so Turtle Records® was born.

I am proud of the high standard we established in the first few years. People are still talking about it! With five partners, however, it was difficult to make it go as a business—perhaps impossible. Since 2008 the label has been completely mine, so maybe that will make it less impossible; I hope so! My other company, Edison Production Company BV, now harbors Turtle.

How did your relationship with Challenge Records develop, and how does it currently work?

Back in my Channel Classics days I was hired to do location recordings for Challenge. When I became an independent producer/engineer, they began hiring me on a regular basis. At some point they discovered my High End network and found a consistent difference in quality and USP whenever I led a project. Eventually Challenge created a brand for my productions, “HQ|NORTHSTAR by Bert van der Wolf,” and put it on the cover, much to my embarrassment; later on I started to appreciate the benefits. Because of the immense trust I received from my buddies at Turtle and the folks at Challenge, the HQ|NORTHSTAR brand is thriving and has become a solid platform for many artists. I also reserve the right to release those productions as part of my personal portfolio on www.spiritofturtle.com.

How else did you develop yourself on the business end?

For years I switched around between hardcore producer/engineer, label manager, and hardware sales/marketing (dCS, Sonodore, Avalon Acoustics Pro, Siltech, others) for High End brands worldwide. That gave me an edge over those who did only one thing, so I got job offers in many adjacent businesses.

Did that surprise you?

I was more surprised by the time lag in consumer response and awareness of my work. It was thirty years before I started to notice more interest. I have just been doing my job, not spending much energy on activities like showing up at award shows or (even) applying for them with productions. Lately things have drifted into new waters; I am doing many more audio shows and interviews in online magazines like this one. Of course, my discography encompasses about 600 recordings, so perhaps it was time for people to start noticing. I still have much to learn about the process.

Any advice?

Well, you’d better love it so much that you have to do it, otherwise it is way too hard!

What do you see as the greatest challenge facing independent producers like you and work like yours in the next 20 years?

It’s the changes in how people consume music. Already it is like water from the tap rather than an exclusive, valuable product.

It’s priceless in the wrong sense.

Exactly. Collecting and fairly distributing revenues is a real challenge for the industry, but if it is not settled soon, many will not survive. Not even me, I’m afraid. My method has always been to build a profile at the highest technical and artistic level. My wife used to ask me, “why can’t good be good enough for once?” But I was convinced that only spectacular is good enough to stay alive. It can be a burden both economically and emotionally. The investments in equipment and time have been staggering.

Will you recommend one or two of your most recent projects?

I am extremely proud of the integral Prokofiev symphonies for Challenge with James Gaffigan and The Netherlands Radio Philharmonic. Also my Bruckner with Jaap van Zweden and the NRPO (Challenge CC72702); Symphonies 1, 3, 6, and 8 are of similar caliber. The Turtle 25th Anniversary album I did for dCS (booklet here, downloads here or here) encompasses several genres and is a very fine example of what I am happy to give the world.

Bert van der Wolf, thanks again for sharing your thoughts. How’s your tennis these days?

Still playing, still coaching! Music and tennis can be quite similar, you know: timing is everything.

[Finally, two clips. First, the opening of Bruckner Symphony No. 1 (Linz version). We hear the tactile thrum of low strings; other colors gradually make their way into the conversation. Dynamic bloom is well caught, reinforcing rhythmic drive even as it highlights the theme’s gradual unfolding.

Second, Liza Ferschtman performs part of the Korngold Violin Concerto with Jiří Malát and the Prague SO (Challenge CC72755). It’s paired with another live performance, the Bernstein Serenade after Plato’s Symposium; both are sonic and expressive knockouts.]

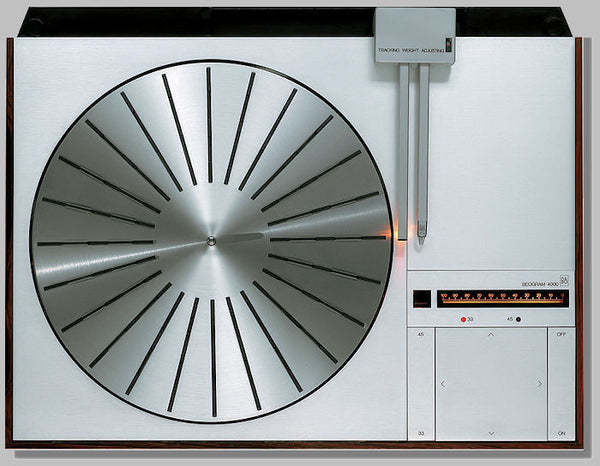

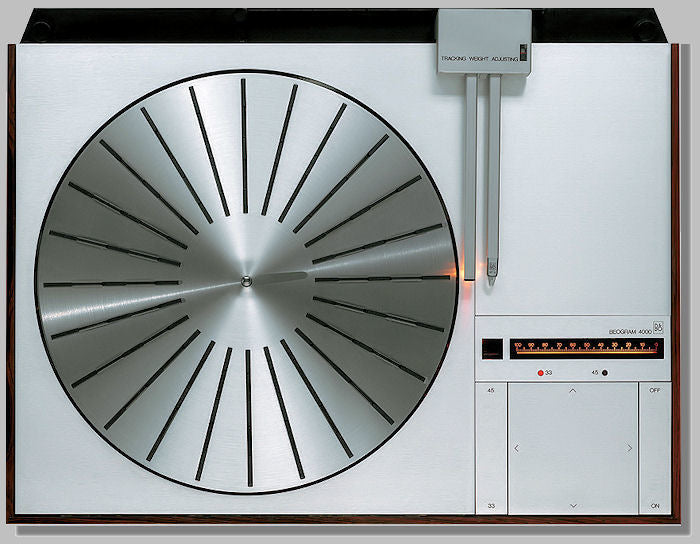

Our header image features the NorthStar studio in Haaften, including Avalon Acoustics Eidolon Special-X and Avalon Sub Special-X (both modified by Neil Patel), Avalon Indra; Spectral Audio DMA 250, 160, and 100’s; dCS Pro DACs, clocking, and DDCs; Siltech cabling; Acustica Applicata DAAD acoustical treatment devices; Nagra-D digital audio recorder; Sonodore/Rens Heijnis custom monitor equipment; and VPI turntable.